This week, we take a step away from politics to talk about two crucial subjects. First, we have the evolution of the Japanese language and its incorporation of Chinese influence. Second, we have the evolution of Buddhism and the arrival of two important sects in the evolution of a distinctly Japanese form of the religion: Tendai and Shingon.

Sources

Adolphson, Mikael S. “Aristocratic Buddhism” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850, ed Karl Friday

Cranston, Edwin A. “Asuka and Nara Culture: Literacy, Literature, and Music.” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 1: Ancient Japan

Weinstein, Stanley. “Aristocratic Buddhism” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 2: Heian Japan

Images

Transcript

Up until now, we’ve been focusing mainly on the complex political culture of early Japan, and with good reason. If you’ve been listening for a while now, you know I’m very much a politics-oriented person; political power shapes so much of the world we live in (and the world our ancestors lived in), and spending time discussing it is, at least in my view, important for understanding the world itself.

But I have been doing you all something of a disservice with that emphasis, because there are some important developments in the realm of culture happening during this time period that we do need to talk about because they’re going to be VERY important going forward. So, that’s what this episode is all about! Today is going to be about language, poetry, and religion (especially Buddhism); next week is going to be about literature and life at court.

And we’re going to start with what’s probably the most important of them all: language and writing.

So: the origins of the Japanese language are a bit unclear. Officially, Japanese and related languages (like Ryukyuan) belong to what is called the Japonic language family, which is not academically considered to be related to any of the surrounding language groups.

It’s fairly clear that early Japonic languages came over to the islands from the Korean peninsula with the Yayoi cultures, with the earlier languages of the Joumon people forming the basis for the Emishi and Ainu languages.

Those languages–of which only Ainu survives today–are language isolates. We don’t know where they come from, nor do they have any clear evolutionary relationship with surrounding languages.

Japonic languages are pretty clearly related to the neighboring Koreanic languages, of which the most prominent is–you guessed it–Korean. The two languages share very similar structures in terms of grammar, which alongside several centuries of vocabulary borrowing means that it’s pretty easy to learn one if you already know the other.

Neither Japonic nor Koreanic languages are at all related to the Sinic language family–the family of Chinese languages, of which the most prominent is the Beijing-style dialect known in the West as Mandarin Chinese.

There are some theories that tie Japanese to the Altaic language family–languages spoken by the people originally from the Altai mountains in Central Asia, of which the most prominent is Turkish. Frankly, I think it’s fairly likely that both Korean and Japanese are descended from these languages, particularly given that they all share a rather unique Subject-Object-Verb structure in terms of how sentences are composed.

But the exact nature of the Japanese language and its relationship to Altaic languages is a controversial subject, and not one we’re really going to explore here because linguistics is far from my specialty.

What’s important for us is that the distinct nature of Japanese as a language made developing one of the most important things for any language–a writing system–rather challenging.

If you know anything about Chinese as a language, you know that it’s very different from Japanese in three crucial respects.

First, the basic order of sentences is different: Chinese, like English, is a subject verb object language, while Japanese and Korean are both subject object verb.

Second, Chinese, like English, is what is called an analytic language, while Japanese is what is called agglutinative. To be honest, I am not a linguist, so I am not going to do a good job explaining this, but as I understand it the key difference is that in agglutnative languages you add more and more syllables to the end of a word (especially a verb) to modify meaning.

Take the verb kaku, to write. To make it past tense, you add the suffix ‘ta’ to the end of it, to make kaita (with some changes to the base verb for vowel harmony). To make it formal, you insert the suffix masu in the middle for Kakimashita. To et Amake it passive, you add the suffix re to make it kakaremashita. In English, these would all be separate words: I was made to write it.

Hopefully this is clear without offending any of the linguists in the audience by oversimplifying.

Finally, Japanese has all these complex modifiers for tense; Chinese simply does not. Chinese grammar is very simple, to the point of honestly making Classical Chinese very hard because of how challenging it can be to interpret the specific meaning of words. Broadly, Chinese only distinguishes between complete and incomplete action–and there’s no verb conjugation at all.

Which, as someone who spent six years trying to learn a Romance language, fills my heart with envy.

Why does this matter? Because the very first writing systems in East Asia were derived from Chinese. The Chinese system of ideographs–thousands of different characters to represent different words or ideas–works very well for the structure of Chinese as a language. But it’s completely incapable of rendering Japanese effectively, at least not without some heavy tinkering under the hood.

Which brings us to the earliest forms of written Japanese, what we call old Japanese. Broadly, this language (and middle Japanese, with the two collectively referred to as classical Japanese) is similar to modern Japanese. There’s the same basic word order and conjugation, but with some more complicated rules behind it that, to be honest, nearly broke my soul during the one trimester of classical Japanese I took.

Our earliest written samples of the language are from the Nara era, with the Kojiki itself being both Japan’s oldest known history and the first piece of actual Japanese language writing we have.

We have older pieces of writing from Japan, but they are all in classical Chinese; given the enormous influence China had on Japan, Chinese became an elite language with a role similar to Latin in medieval Europe, Arabic in the Islamic World, or Sanskrit in India. Knowing Chinese served as both a status marker for members of the elite (demonstrating they were ‘truly educated’) and as a way for members of said elite who spoke different languages day to day to talk to each other and share ideas.

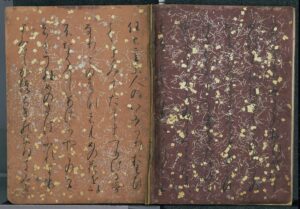

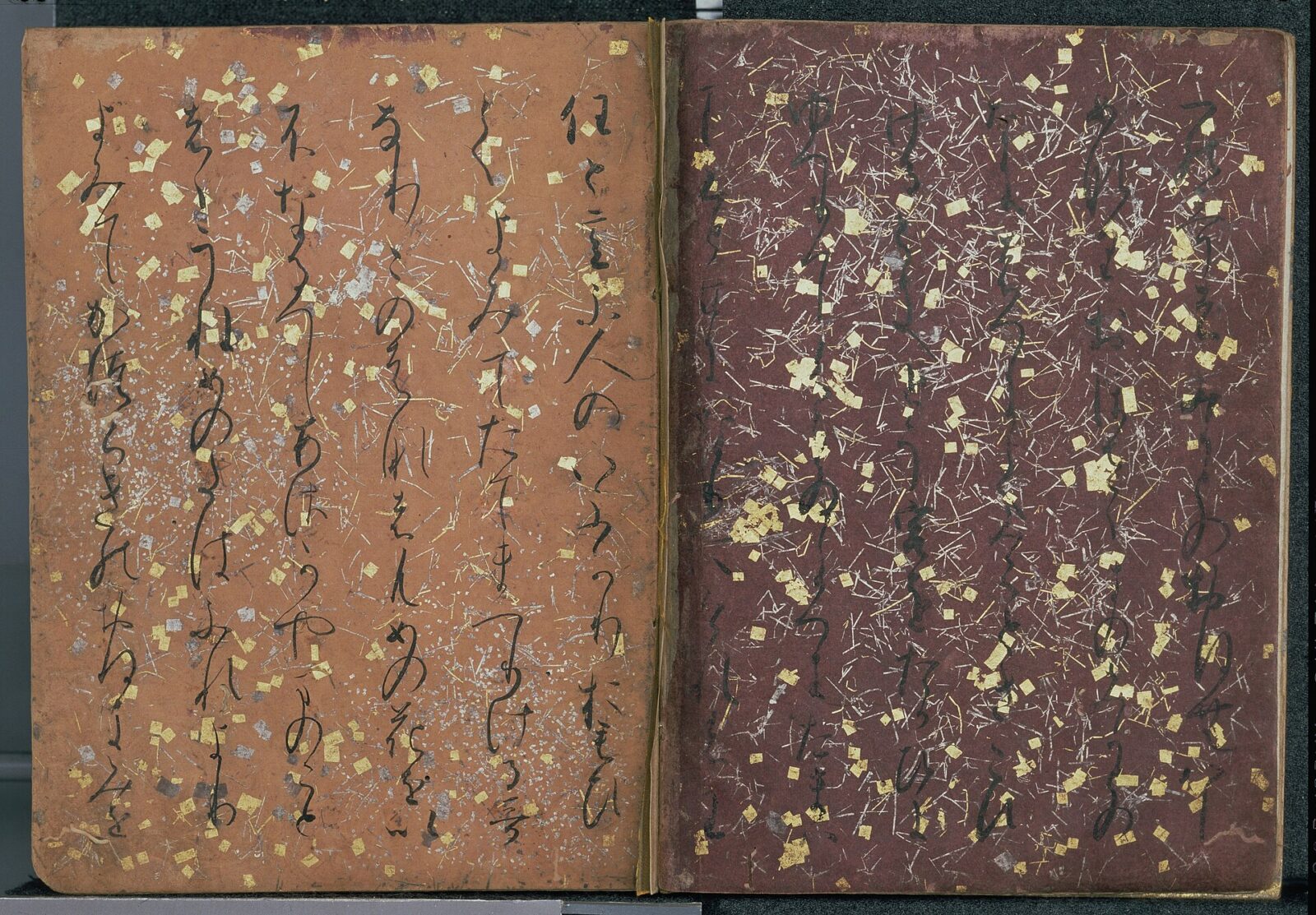

The earliest form of Japanese writing we have is called Man’yogana, and originated from the necessity of including Japanese words in that classical Chinese correspondence. For example, a Japanese courtier writing to a counterpart in China would have to figure out a way to render their own name in their letter–to do so, they would pick Chinese characters that were pronounced similarly to the Japanese sound they were intended to represent.

That approach in turn eventually formed the basis of Man’yogana, which uses Chinese characters phonetically to transcribe the sounds of Japanese.

If you are a speaker of Chinese or just know your ideographs–called hanzi in Chinese or kanji in Japanese, literally meaning “Han (Chinese) characters”–these look like complete nonsense.

After all, the Chinese characters are being chosen for their sound, so if you try to read them based on meaning you get absolute gibberish.

Man’yogana as a writing style is, of course, best associated with the Man’yoshu–literally “the collection of 10,000 leaves.” The text is a compendium of poems–not quite 10,000, as there are precisely 4536 poems in the text, but in East Asia 10,000 is often used to mean “a great many.” And certainly, over 4500 poems counts as “a great many!”

Poetry as a medium is of course very much associated with the refined literati of Asia; for much of Chinese history, the ability to compose poetry has been associated with the virtues of refinement, good taste, and overall quality of character. So it makes sense that Japanese aristocrats, looking to model themselves on their Chinese counterparts, would develop an interest in poetry as well. The Man’yoshu itself represented an attempt to catalogue the poetic accomplishments of Japan’s best, compiled by one of the leading men of the time (Otomo no Yakamochi), likely with sponsorship from either Emperor Shomu or Empress Kouken (dating the text beyond “some time in the 750s” is a bit challenging).

Now, we’re not going to dive too deeply into the Man’yoshu here because that could be an episode entirely in its own right. I do want to note a few things about it that are unique, though. First, it represents a variety of different poetic styles–unlike later poetic compendia, which would generally confine themselves to a single format of poem. The text contains mostly 31-syllable tanka (short poems), but also chouka (long ones, as many as 149 lines!), as well as a sprinkling of kanshi (Chinese-style poems), bussokusekiha (a type of Buddhist memorial poetry), and even a few folk songs.

As the folk songs bit might suggest, it wasn’t just aristocrats whose works were included in the Man’yoshu; the collection included several poems by common people, which would very much not be the case in later compilations.

The poems also employ a somewhat different style than later generations. Later poetsi n Japan would avoid metaphors or allusions they considered too direct–for example, a poem trying to get you to consider the Buddhist theme of worldly impermanence would never be so direct about things as to directly depict a corpse. That’s way too on the nose, so to speak; a human body is way too obvious a metaphor for the transience of life and the unavoidable nature of death, and including it would be considered, for lack of a better term, basic.

Similarly, a poem about love would never actually depict acts associated with romantic love, like holding hands or (god forbid such vulgarity) kissing!

Yet as Robert Borgen and Joseph Sorensen indicate in their essay on early Japanese literature, both these symbols are used quite freely in the Man’yoshu: an indicator of how poetic taste particularly among the elite would evolve in the future.

Both language and poetry would continue to evolve and change over the course of the Nara era, and especially after the move of the capital to Heian/Kyoto. During the early Kyoto years, poetry briefly fell out of favor as a form in favor of longer form prose literature, with the emperors of the time sponsoring a series of literary compendia of great works of the time. By the 900s, poetry would once again come to dominate as the preferred medium of the elite–though those literary compendia did continue to establish the precedent of emperors sponsoring literary activities, which would become an important facet of courtly life going forward.

The 900s are, poetically speaking, most associated with the Kokin Wakashu (or Kokinshu for short–roughly, “Collection of Poems from Ancient and Modern Times”). Compiled in 905 under the supervision of one of Japan’s greatest poets, Ki no Tsurayuki, the Kokinshu came to be something of an aristocratic tastemaker going forward. Unlike the Man’yoshu, it only contains one type of poem–waka, or Japanese style poems. Those poems (there are over 1000 of them!) are spread across 20 chapters that are organized thematically around the four seasons, and then major literary themes (with pining for one’s love being the most important, as literally 1/4th of the text focuses on that subject).

While these are very much the ancestors of modern haiku, these poems different in a few key ways, most notably a reliance on clever wordplay and allusions over simplicity and clarity.

As a result, unlike later haiku masters, the Kokinshu never found much of a following outside of Japan because the text is very hard to appreciate in translation.

The Kokinshu was the first in a series of imperially sponsored poetry anthologies that would be compiled regularly until the early 1400s, when the court would fall on hard times financially–and as the first such collection, the Kokinshu would be looked at as something of a model for the composition of poetry in later years.

There’s a LOT more to say about it, of course, and if you’re interested take a look at episode 447 for more information.

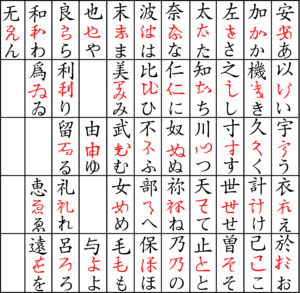

As for the language, it was also during the Heian period that one of the most important shifts in the Japanese language took place–the development of the kana syllabary.

Simply put, writing Japanese using only Chinese characters was not terribly efficient–so over time, people began to use modified forms of said characters purely phonetically. The shape of the characters was very visibly derived from Chinese, but they were visually distinct enough to be distinguishable. This became hiragana, the entirely phonetic script that first year Japanese students around the world know and love today.

Hiragana began to emerge in the 800s, but did not become a universally accepted way of writing Japanese. The association of Chinese with literariness, sophistication, and just general good education meant that Chinese remained the official language of government and of elite culture, particularly for aristocratic men–who, if they hoped for a job within the growing government bureaucracy, needed to be able to write and read in Chinese since that was how recordkeeping was done (and served as a general marker of education, much as reading and writing in Latin did in Europe up until pretty recently).

It was primarily aristocratic women, who did have the resources to learn to read and write, but who were not expected to master the complexities of Chinese since they could not serve in government, who were associated with hiragana writing. This association was so strong that hiragana was sometimes called onnade, or women’s hand, contrasted with writing in Chinese–which was called otokode, or men’s hand.

The fusion of these two styles, characteristic of Japanese today, would take place over the course of the next few centuries and eventually lay the groundwork for the language as it exists now. Those developments were still a ways off in the early Heian era, though–and at any rate Chinese specifically continued to have currency as the language of education and elite sophistication all the way down to the end of feudalism in the mid-1800s.

It’s also worth noting that all this talk of literature and the arts presents a somewhat distorted view of the Japanese aristocracy during this time. Up until pretty recently, the image of the Heian aristocracy that tended to dominate was one of effete literati more concerned with the quality of their poetic compositions than anything else. That image emerges from a somewhat selective reading of sources like the Kokinshu, which certainly do have a great deal to say on that subject–the idea being that all this explains why said aristocrats will be displaced successfully from political power in the coming centuries by more rough and tumble warrior types from the provinces who did not have patience for all this poetic foolishness.

But that’s a bit unfair. As we’ve seen over the last few episodes, it’s not like these aristocrats did not care about political power–fighting over said power within and between the imperial family and various clans has kind of been the theme of our episodes so far. And all those famous poets? Their talents didn’t exactly make them powerful. Ki no Tsurayuki, for example, never made it far up the government hierarchy despite being one of the most celebrated poets of his age–he was made a governor of a remote and unimportant province (Tosa, modern Kouchi prefecture) and awarded some middling bureaucratic posts and aristocratic ranks (his highest in his lifetime was junior fifth rank, upper grade, about 2/3rds up the chart, though he was posthumously promoted). By comparison, the most powerful political leaders of the period were rarely celebrated poets.

And it’s not like Heian courtiers ONLY cared for aristocratic and refined things. Great writers like Mursasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon (about whom more next week) noted the popularity among their fellow aristocrats of something called imayo, literally “modern songs”, essentially vulgar popular ditties sung by shirabyoshi sex workers to entertain clients. Said songs were so popular that a later emperor actually compiled them into their own collection (Ryoujin Hishou, roughly “songs to make the dust dance”).

And they were pretty vulgar by the standards of the time. Here’s a rough translation of one, for example: Wine cups and/fish that cormorants eat and/women: one never tires of them/ let’s have sex, the two of us!

Not what I’d call subtle. So, while it’s important to know about high aristocratic taste, we shouldn’t make the mistake of assuming that “high class” writing was the only thing said aristocrats liked.

Beyond language, of course, one of the most important cultural aspects of this period was the rapid growth of Buddhism as a religion. We covered the origins of the religion in brief in a previous episode so I won’t rehash them here–but just as a quick refresh, Buddhism as a religion was 1000 years old already by the time it first arrived in Japan somewhere in the mid 500s (the exact date is unclear).

The earliest forms of Buddhism to arrive in Japan came from China by way of Korea, and those continental connections made Buddhism, for lack of a better word, fashionable.

This also meant that Buddhism was, early on, a deeply aristocratic religion in Japan. As we’ve already covered, of course, it was one of the aristocratic clans–the Soga–who first began to propagate the religion in the country, and the great temples of Nara were built either by those clans or by the imperial family itself.

In addition, at this point in history, East Asian Buddhism–Mahayana Buddhism, in other words–was not quite yet what it would be. One of the major splits that would emerge between Mahayana and other branches of Buddhism (most notably Theravadan Buddhism) was around the question of karma and enlightenment. Theravadan Buddhism, and generally most forms of early Buddhism, emhpasized the idea that you had to go through several different lives accumulating good karma–as expressed in increasingly favorable rebirths–before attaining enlightenment and escaping the cycle of reincarnation. “Favorable rebirth”, in this context, came to refer to birth into aristocratic families (and often birth as a man)–making Buddhism very much the ally of political power and elite status.

Early Japanese Buddhism very much reflected this context; the vast majority of monks and Buddhist institutions, with only a few exceptions, focused their efforts on the nation’s elite. Temples were concerned not with spreading the message of the Buddha to the masses, but with offering their spiritual power in defense of their elite patrons–and thus justifying their continued substantial economic support.

Chief among these dominant forms of early Buddhism was the Hossou sect, whose member temples enjoyed the patronage of the powerful Fujiwara family, with the most powerful Hosso sect temple being Kofukuji in Nara.

The move of the capital to Kyoto from Nara was, in part, a way for members of the court to escape the power of existing Buddhist institutions, which over the course of the Nara era became a major power block within the government.

And it was over the course of the early Kyoto years–the Heian Period, as it’s called, a name that comes from an older moniker for the city–that Buddhist theology in Japan began to change, driven by the emergence of two new sects associated with the famous monks Saichou and Kuukai.

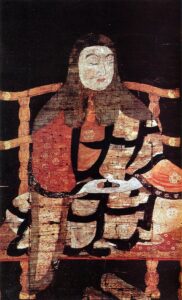

Saicho was born in 767 in Omi province around Lake Biwa, but moved to Nara as a young man to become a Buddhist monk at Todaiji. While at Todaiji–he was ordained there as a monk in 785–he became interested in a new sect of continental Chinese Buddhism called Tian’tai (Tian’tai being the name of a mountain where the Chinese monk who founded the school opened his first temple).

We’re not going to get too deep into the theology of Tendai, except to note that it was, in a certain sense, the first “Chinese sect” of Buddhism–the first one to rework Buddhist theology to incorporate insights derived from native Chinese philosophy, and thus to create a uniquely Chinese model of Buddhist theology.

For us, what matters is that Tiantai sect Buddhism rejected this notion of accumulating karma over time for rebirth, instead emphasizing the idea that anyone could attain a positive rebirth at any time–it was purely a matter of one’s efforts in pursuit of enlightenment.

This idea spoke to Saicho, who the very same year he was ordained left Todaiji behind to found a small monastery atop Mt. Hiei, overlooking Lake Biwa.

Which was a fortuitous choice on his part, because a few years later the announcement came that the imperial court was moving to Kyoto–very close to Mt. Hiei, which fortuitously was also to the northeast of the city.

That direction has some inauspicious associations, which is why in both China and Japan it was common to locate religious institutions to the northeast of the capital–thus warding away said bad influences. Mt. Hiei’s temple–known to history as Enryakuji–would serve this purpose, and before long Saicho himself was offered sponsorship by the imperial court, which he accepted in 796.

By 802, Saicho had begun to distinguish himself from his Todaiji roots and more openly claim a connection to Chinese-style Tiantai Buddhism (called Tendai in Japanese).

Saicho was also the one to introduce an important theological innovation to Japanese Buddhism: an emphasis on the Lotus Sutra, which would become one of the foundational documents of many of the branches of Japanese Buddhism.

The Sutra of the White Lotus of the True Dharma, or “Myouhou Rengekyou” in Japanese, is of unknown authorship–all we know is that it was composed by Indian monks in the centuries after the death of the Buddha himself.

The theology of the text is, to be frank, way more dense than we can possibly cover here–simply put, it’s a text on the variety of methods to be used for the salvation of sentient beings and the obtaining of enlightenment.

In the process, it establishes a complex Buddhist metaphysics that would form the groundwork for future sects like Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren–all of which we’ll talk plenty about in the future.

Saicho was deeply enamored with the sutra, to the extent that he asked for and received imperial permission to go to China for several years to study at Mt. Tiantai. The teachings he returned with–derived primarily from the Lotus Sutra–formed the basis of the growing Tendai sect. However, Saicho was never as popular as the other monk we have to discuss was–the independence of the Tendai sect from existing temples and teachings was actually not fully recognized until after his death in 822. As a result, Saicho spent a good chunk of his career fighting against pushback from the monasteries of Nara, which attempted to circumvent Saicho’s attempts to create an independent sect of his own.

As a result, Enryakuji would struggle financially for a good chunk of its early history, and Saicho’s sect–while it would eventually grow quite substantial and powerful–would not become as popular as that of the other Buddhist thinker we have to talk about today.

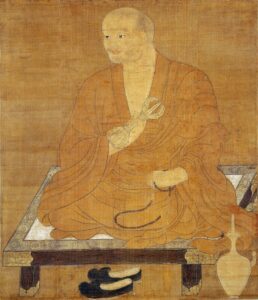

The man known to history as Kukai was born on the island of Shikoku to a minor noble family, who in turn sent him to what was then the capital at Nagaokakyo at the age of 14 to study Confucian thought. However, Confucianism’s emphasis on politics did not appeal to the young man, who instead was far more enamored with Buddhism.

It is unclear exactly how Kukai entered Buddhist monastic life; he appears to have privately taken Buddhist vows at first and then, when the capital moved to Kyoto, began devoting himself to Buddhist missionary work. This was how he came to the attention of the imperial court, resulting in Kukai being attached to the same Buddhist mission to China of which Saicho was a part.

Kukai, however, ended up making far better use of his time in China–he went not to Mt. Tiantai, but to the capital of the Tang dynasty at Chang’an. After studying Buddhism at the heart of the empire for several years, he spent several years at Ximing Temple just outside the capital, becoming a student of one of the great Buddhist masters of his age: Huiguo.

Huiguo’s approach to Buddhism was deeply esoteric: if you don’t know what that means, esotericism is essentially an approach to religion that involves the use of complex symbolism which one engages with on an individual level in order to attain a profound understanding of Buddhist teaching. The usual vehicles for this would be mandalas (visual representations of the cosmic order), the chanting of mantras (phrases endowed with some kind of spiritual meaning), and the use of mudra, physical movements intended to symbolize a certain idea.

Kukai found himself deeply attracted to Huiguo’s teachings, referred to as the Zhenyan (true word) sect of Buddhism. And so he took them back to Japan–where those same characters are read “Shingon.”

Shingon sect Buddhism proved extremely popular with the imperial court, far more so than even the Tendai sect–probably because the esoteric nature of the teachings appealed to a court aristocracy that was extremely fond of anything that had the appearance of providing magical or supernatural powers.

This popular support made it far easier for Kukai to support the independence of his his growing Shingon sect from the temples of Nara, and before long he received permission to build his own temple complex on Mt. Koya to the south of what’s now Osaka.

Kukai’s temple, Kongobuji, remains the heart of Shingon Buddhism in Japan down to this day.

Kukai also managed to snag a few other powerful concessions indicative of the popularity of his ideas; chief among them, he was able to secure an imperial decree that only monks of his sect could reside at Touji, one of the temples of the new imperial capital at Kyoto where he himself had been abbott for a time. The “fliping” of such a prominent temple to Shingon, in turn, was indicative of the support the sect enjoyed among the capital’s elite–as was another decree, issued the year of Kukai’s death in 835, that the imperial court would construct a Shingon temple within the imperial palace itself where Shingon rituals would be performed at the start of each new year for the protection of the court itself.

Now, Shingon and Tendai sect Buddhism would eventually become major competitors with the existing Buddhist sects, especially Hosso–during the 900s, the Tendai head temple of Enryakuji would be home to two enormously talented abbotts, Ennin and Enchin, who together would help drive the popularity of the Tendai sect up to the same level as Shingon among the court nobility.

This competition among Buddhist sects matters for us for a few reasons. First, the fight over the course of the 800s and 900s to establish the independence of Tendai and Shingon from older temple structures would result in a fundamental remaking of the nation’s religious bureaucracy. Up until this point, temple lineages were carefully controlled by a state-run bureaucracy that existed as a part of the imperial government. However, the growing independence of sects like Tendai and Shingon led to the dissolution of said bureaucracy as outmoded, allowing temples and sects far more independence in regulating their own internal affairs.

That growing independence, however, meant that the temples also no longer received as much funding from the court–which had been the rationale for the supervisory power the court assumed. This in turn made the temples even more dependent on “fishing” for patronage from powerful families, whose funding could make or break a given temple.

And this would have powerful implications down the line, because aristocratic families were willing to give that favor. Temples like the Tendai sect Enryakuji, the Shingon sect Kongobuji, and the Hosso sect Kofukuji were able to secure huge amounts of cash as well as land grants in the form of shoen–estates gifted by the government as tax-free parcels to support them. This in turn made the most popular temples fabulously wealthy, to the point where the temples themselves became powerful institutions in their own right.

This is also when the temples, understanding the necessity of protecting the powers they had accrued, began to develop bands of armed followers to defend them–in future domestic conflicts, powerful Buddhist temples would actually serve as armed players within the realm’s politics.

Aristocratic support also came with the expectation that temples take on members of the aristocracy interested in Buddhist monasticism–and with the unspoken but powerful assumption that members of elite families who joined a given temple would be quickly promoted up the monastic ranks as a way of securing yet more favor from that family.

As a result, these “establishment” temples began to develop a leadership structure dominated by members of the aristocracy–the sons of powerful clans, or sometimes even of the imperial family, whose presence and elevation to leadership roles was intended to symbolize the connection between the temple and its patrons.

Buddhism was thus further entrenched as a religion of aristocracy–but even so, at the same time, the seeds of popular Buddhism were being planted. Saicho and Kukai’s theology was a part of this, of course, with its distinctly Mahayana emphasis on the idea that anyone could attain enlightenment with the right effort.

So too was the growing visibility of Buddhism in the public eye. A part of the imperial court’s justification of its support for Buddhism was the popularization of a rather distinct theology called honji suijaku–very roughly, “true essence and reflected manifestation”. In this theory, Buddhist deities, for lack of a better word–the Buddhas, the boddhisattvas, and the various mystical figures of Buddhism, were the honji, the true essence–while the gods of the native Japanese tradition were suijaku, manifestations of these Buddhist deities in a distinctly Japanese form.

For example, Amaterasu was often glossed as a manifestation of Avalokitesvhara (or Kanzeon, to use her Japanese name), the Boddhisattva of mercy in the East Asian tradition.

This theology was intended to explain how the court could support two different religious traditions (and show they were not that different), and led to a growing intermingling of the two–with shrines and temples often sharing grounds, and shrine gods being set up as protector dieties of Buddhist institutions.

This in turn led to more and more non-aristocratic Japanese–who were very much not the target of these elite institutions–being exposed to Buddhism in larger numbers. And some Buddhist ideas began, thanks to this exposure, to find purchase outside of the elite in larger numbers.

This would lay the groundwork for the explosion of popular Buddhism in future centuries, but we’re still a long way off from that time.

Have we already had an episode on the Komeito and all it’s juicy scandals?

The Altaic hypothesis has long since been discredited by its own proponents. Altaic isn’t even a language family anymore. All of the Altaic “members” just share areal features but no genetic lineage. Japanese and Korean form a sprachbund but aren’t related, like Aztec and Maya. Japonic probably came from the peninsula or it could have come from Taiwan with the Austronesian languages. There’s no clear consensus. Unfortunately, there’s still outdated articles floating around about how Japanese is Altaic.