This week on the podcast, we’re all about literature. We’ll be exploring the varieties of poetry and prose that have made the Heian period one of the golden ages of literary flourishing in Japanese history.

Sources

Sorensen, Joseph T. “Canons of Courtly Taste” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850

McCullough, Helen Craig. “Aristocratic Culture” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol II: Heian Japan

Brower, Robert, and Earl Miner. Japanese Court Poetry.

Images

Transcript

When we talk about classical Japan–often referred to as the Heian Period after the imperial capital, and running from 794-1185 CE–the first thing that tends to come to mind is literature.

The classic canon of Japanese literature does, of course, run a bit further back than the Heian era–the poems of the Man’yoshu and mythohistories like the Kojiki predate it–but the works of Heian Japan are generally far more widely read and better regarded today.

In many ways, that’s because they’re just more accessible. As we discussed last week, the Japanese language had begun to evolve into something that’s at least recognizably related to modern Japanese by the early Heian Period.

If you want to read the Man’yoshu, you’re going to read it in translation even if you’re a native Japanese speaker–the Man’yogana hybrid writing system is just utterly impenetrable unless you study it academically, to the point where it might as well be a different language.

By comparison, the classical Japanese of the Heian era is certainly very different from modern Japanese, it is at least more accessible than the Man’yoshu–which, without alteration, would be incomprehensible to a native speaker today.

But to be honest, I don’t think language is the only reason–and I’m not alone in that opinion. For centuries now, the literature of the Heian period has been held up as the time when a distinctly “Japanese worldview” began to emerge in writing–whatever exactly that means. Later Japanese nationalists would point to the classic works of this period, and especially to their emphasis on aesthetics and worldly impermanence, as examples of the distinct nature of Japanese culture itself.

And of course, that means the subject of Heian literature is of some importance to us here–and we’re going to try and do a survey of that subject today, though I want to say up front that this episode is going to be FAR from comprehensive and instead focus on introducing major themes and ideas, which you can investigate further if you’re so inclined.

So, first thing’s first: what conditions are these famous works emerging from?

The first thing to understand about classical Japanese literature is that it often bridges what we think of as a pretty stark genre divide between prose and poetry. In English, these are very distinct forms of writing; in Japanese, both classical and modern, there’s a good amount of overlap. Poems are often accompanied by narrative prose describing the conditions under which they were composed (because the terse and referential nature of the poem itself might not otherwise be clear), and prose is often interspersed with poetry–the ability to compose poems being one of the markers of education and good culture for a member of the nobility during this time.

As we mentioned last week, poetry has a long history in Japan, going back to the earliest moments in recorded history. The general pattern of the Japanese state during this time, as we’ve seen over the last few episodes, was to model itself off designs taken from imperial China–and in the social and cultural realm, things were no different.

However, after the first century of the Heian period, the nature of popular poetry began to shift. For the previous few centuries, broadly, there had been something of a genre divide between what were called kanshi–styles of poetry written in Chinese and based on the model of Chinese poets–and waka, or Japanese-language poems.

The precise genre differences are a bit arcane unless you’re very into poetry as a subject; for us, the most important thing is the different languages used in these two styles of poetry.

By the late Nara and early Heian periods, kanshi–Chinese-style poems–had come to dominate public spaces. Kanshi poets were the ones who received support from the government and whose works were published in official anthologies, and kanshi was generally held up in public as the more sophisticated narrative form.

There are a few reasons why this was the case, though by far the biggest was the fact that, since the business of state was conducted in Chinese at this point, an educated man had to be able to read and write that language–and writing kanshi was a great way to demonstrate that talent, and to demonstrate your ability to live up to the standards of cultured gentlemanliness established by the great dynasties of the continent.

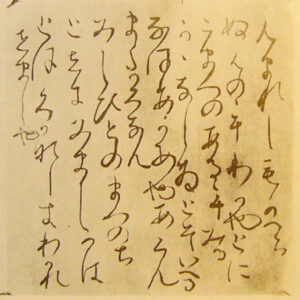

Waka poems in Japanese, meanwhile, were still composed, but not celebrated as publicly. The fact that they were often written in the emerging hiragana, or phonetic syllabary, rather than in Chinese characters, meant they were often caricatured as lacking in sophistication or refinement. Waka poems were also written primarily by aristocratic women during this period–who generally were not educated in Chinese since that was the language of government, but who could read and write Japanese using hiragana–and so taken less seriously as a form of art.

By the 800s, waka poems were often confined to private correspondence, composed as part of an exchange of letters or attached to a social invitation. As the later great waka poet Ki no Tsurayuki put it, waka poems of this time were, “nothing but empty verses and empty words…[and] the province of the amorous.”

In other words, they were mostly good for dumb jokes or hitting on people.

Of course, that didn’t last–though fortunately for those of us with cheap senses of humor, the dumb jokes would never entirely go away. Still, the poetic winds did begin to shift in the late 800s, as there was a revival of interest among Japan’s elite in waka as a form.

There are a few reasons why this shift took place. For a start, as China’s Tang dynasty began to weaken and falter, the prestige of imitating continental styles waned with it.

Over the course of the Heian period, government positions also became increasingly a matter of inheritance from one’s parents rather than merit and hard work, meaning there was less incentive for children of the elite to exert themselves in learning Chinese if they were not of a scholarly inclination.

Perhaps the biggest incentive, however, was the growing cultural power of women–who suddenly found themselves in the middle of politics.

As we covered two weeks ago, one of the main ways the Northern Fujiwara family came to dominate the government was through marriage alliances with emperors they could then reduce to figureheads, governing themselves as appointed regents.

And one of the main ways said regents controlled the emperors was via marriage–to Fujiwara women, who in turn would also give birth to new imperial heirs.

That meant that the ability of said women to be charming–in part, by showing off poetic skill and refinement–was suddenly a matter of extreme political importance, since said talent could draw an emperor’s eye and ensure the power of the family (and of course, the prestige of the woman lucky enough to give birth to a potential heir).

And so over the last few decades of the 800s, waka began to shake the perception that it was a frivolous form–instead, it returned to the limelight, where it would remain in some form going forward.

The composition of Chinese-style poems did not stop, of course, but it was also no longer as prominent in the public literary world as it once had been.

Still, it would take a while for waka to re-enter the world of respectable literature, so to speak. The best example of this is one of the earliest classic works of Heian literature, Ise Monogatari–ascribed to an aristocrat of imperial ancestry named Ariwara no Narihira.

We’ve covered Ariwara and Ise Monogatari in substantial depth back in episode 446, so I will not retread that ground completely here. But there are a few aspects of Ariwara’s literary career that are important to an overview of literary trends in classical Japan.

First, Ariwara himself was both a descendant of and a political friend to several factions within the aristocratic world and the imperial family opposed to the power of the Northern Fujiwara clan.

Given how the Northern Fujiwara were able to more or less take control of the government starting in the 850s, this obviously was not a great political position to be in, and by the latter part of the century Ariwara and his allies found themselves more or less totally on the political outs.

And many of these men, including Ariwara, responded to being bounced from public life by retiring into private life, building what were in essence social circles around powerful aristocratic or imperial supporters. In Ariwara’s case, he fell in with a group of literarily inclined aristocrats who were a part of a literary salon that would meet at the home of Prince Koretaka–a prince of the imperial family who had once upon a time had ambitions of being seated on the throne, but who had been denied that chance by the Northern Fujiwara, who had placed a prince related to them on the imperial seat instead.

Like the literary salons of European history, ostensibly these were social gatherings to have high-minded erudite discussions about important things among friends–but they were also an excuse to get drunk together and enjoy life, or at least commiserate about those damn Fujiwara bastards.

It was during his time as a part of Prince Koretaka’s salon that Ariwara’s compositions–what became Ise Monogatari–came together, almost certainly a compilation based on his own private collection of writings and diaries which are unfortunately lost.

And this early classic of waka poetry did not, unfortunately, shake the genre’s reputation as being nothing but a thinly-veiled format for sexualized escapades. The early chapters of Ise Monogatari–the ones most likely to have been written by Ariwara himself–are pretty much just prose describing his amorous encounters (which might have been based on real experiences, but there’s no way to be sure) followed by some admittedly well written poetry about his liaisons.

It was only after Ariwara’s death in 880 that future writers added later chapters to the text where the main character grapples with more erudite themes around the impermanence of such wordly pleasures–an attempt, simply put, to class up the original text a spell.

It would not be for a few more decades yet that waka would attain prominence as a literary form, a development driven by one of the most famous poets in Japanese history: Ki no Tsurayuki.

We know very little of Ki no Tsurayuki’s life or career–he probably got his start as a part of one of these literary salons, possibly the same one Ariwara no Narihira came up in.

He was from a fairly minor family politically speaking, and never made it that far up the political ladder–his highest ranking posting was as a provincial governor to one of the most remote parts of the country (Tosa Province, now Kouchi prefecture on Shikoku’s Pacific Coast).

His talent for poetry is probably what allowed him to climb as high as he did; being involved in these salons was a great way to come to the attention of those with the power and influence to accelerate a career beyond what otherwise would have been possible for a man with only a minor background.

However, Ki no Tsurayuki’s poetic contributions are far better regarded than his political ones. As we discussed last week, he was the chief editor of the Kokin Wakashu (or Kokinshu for short–a collection of Japanese poems from ancient and modern times, roughly). This was the first government-sponsored collection of waka poetry, and Ki no Tsurayuki’s editorship of it would have massive influence on how this genre of poetry was evaluated going forward.

He was not solely responsible for the restoration of waka poetry to prominence or for giving it a role outside of bawdy jokes, to be clear; for decades now, waka’s popularity had been rising for all the reasons we’ve already discussed. Where once, a major occasion in the life of an emperor would have been commemorated with a Chinese-style kanshi poem, now waka were the go-to. And where once, men of poetic talent had shown off their skills in competitions for Chinese poems, now utaawase, or poetry contests, for waka were far more common.

But Ki no Tsurayuki’s collection of poems in the Kokinshu, and his Japanese-language preface to the text explaining his views on what made for a good waka poem, DID prove extremely influential.

Also he did write 102 of the over 1000 poems in the collection (the most by any one single author), which does help his legacy quite a bit but kinda feels like cheating given that he was the editor.

Anyway: Ki no Tsurayuki’s preface is probably the most important part of the work–it begins with a valorization of Japanese poetry as a medium, noting that, “It is poetry which, without effort, moves heaven and earth, stirs the feelings of the invisible gods and spirits, smooths the relations of men and women, and calms the hearts of fierce warriors” before moving into a critique of the poetry of the time as insipid nonsense that ignores the heart of the genre.

This section includes some dunks by name on poets he did not care for, including Ariwara no Narihira, whose poems, “ are like withered flowers, faded but with a lingering fragrance.”

After engaging in some petty smacktalk, Tsurayuki turns toward a theory of Japanese poetry as having three basic components. The first two are kokoro (spirit) and kotoba (words)–roughly these would be having a clear theme and having a clear subject.

And yes, I am simplifying the meaning here a lot; if you’re curious for more detail about these concepts, check out episode 447.

The final element is sama, roughly “form” or style–this is basically imitating the formal demands of Chinese poetry, with their focus on clever references, wit, and oblique discussion of subject matter rather than making the poem too obvious or clear in its message.

The focus is on producing an “elegant confusion” in the reader as they grapple with the meaning of the poem, and with provoking a certain mental state or response in a reader rather than aiming to realistically portray a scene.

The overall idea is to balance intellectual and rational approaches to appreciating a work, creating a wholistic human experience in engaging with the poem.

And that notion would more or less come to define what waka poems were going forward. The Kokinshu was the first of seven government-sponsored poetry compendia created over the course of the Heian period: (Kokinshu (ca. 905), Gosenshu (Later Selection, ca. 951), Shuishu (Collection of Gleanings, ca. 1006), Goshuiiishu (Later Collection of Gleanings, 1087), Kin’youshu (Collection of Golden Leaves, ca. 1126), Shikashu (Collection of Verbal Flowers, ca. 1151), and Senzaishu (Collection of a ThousandYears, ca. 1188).

And of these, Kokinshu is by far the best known–and while other collections would attempt occasionally to mix up the formula he created, Tsurayuki’s approach to waka would remain the definitive one for centuries going forward.

Future poetic masters (most notably the great Fujiwara no Teika) would hold up Kokinshu and Ki no Tsurayuki as the guy, the one who had figured out what Japanese poetry should be, and going forward the composition of waka would be all about building upon (or less charitably, simply attempting to replicate) the notions of poetic brilliance Ki no Tsurayuki defined.

Of course, poetry was not the only field of Heian literary accomplishment, and here we must turn our attention to the world of prose.

Of course, that doesn’t mean we leave poetry behind–we’ve already talked about Ise Monogatari, which blended the two forms to give some context to the amorous poems of Ariwara no Narihira.

But there’s one key difference between poetry and prose in the Heian tradition: most of the most famous works of prose, including perhaps two of the most famous texts in Japanese history, were written not by men but by women.

Hellen Craig McCullough makes an excellent point as to why in her essay on the Heian court and art: “There were, in effect, two kinds of literature at the Heian court: poetry, which was the recognized public genre, suitable for both masculine and feminine attention; and narrative prose, which was largely relegated to the rear palace [where the women resided]…. The imperial ladies thus presided over the only [universal] literary centers of the day, embracing both poetry and prose in their interests, and encouraging literary activity both indirectly, by setting a prestigious example, and directly, by patronizing individual writers.”

In other words, because poetry was considered to be a public genre, both men and women wrote it–but prose was not, and therefore it was largely confined to women.

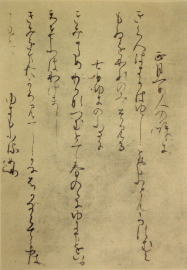

That development took some time; indeed, alongside Ise Monogatari, the other early work of Heian prose was Tosa Nikki, the Tosa Diary, written by none other than Ki no Tsurayuki and describing a return journey from Tosa province (where he was governor) back to Kyoto.

Tosa Nikki, however, is still revealing of the shifting trend–because it’s a semi-fictionalized account that Tsurayuki wrote from the perspective of a woman.

Why? Well, he didn’t explain his reasoning, but we have a few guesses.

For a start: nikki, or diary, had up until this point referred as a genre to official day-to-day accounts written by men in Chinese, and often made for dry reading. Much of the content was just “on day x, the weather was y, and so-and-so did z.” Tosa Nikki is of course not that; the protagonist starts off by saying that she is ignorant of Chinese styles and conventions, and the whole text is written in Japanese using the phonetic alphabet (associated primarily with women still at this point).

So what is probably going on here is a kind of literary experiment, where Ki no Tsurayuki is creating imaginary conditions where he feels it would be appropriate to compose a diary in Japanese, using what he understands to be Japanese literary conventions instead of Chinese, and then seeing what happens.

This has made Tosa Nikki something of a touchstone in terms of conversations around gender and language in Heian Japan–it comes up in pretty much every discussion of the evolution of the written Japanese language, since the phonetic kana characters it’s composed in are so associated with women, who were taught to use kana instead of Chinese ideographs.

It was also very influential on later writers; Tosa Nikki, though it’s ostensibly a ‘private diary’, was clearly intended to be circulated so that Ki no Tsurayuki could in the time honored manner of male writers everywhere show off how good he was at writing about women, and in the process helped pioneer the idea that diaries could be literature.

And going forward, quite a few women would write literary diaries that were extremely highly regarded in future years: three of my personal favorites are the Kagero Nikki, or Gossamer Diary, composed some time in the 980s, the Izumi Shikibu Nikki (Izumi Shikibu’s Diary) composed around the year 1000, and the Sarashina Nikki, or Diary of Lady Sarashina, from around 1060.

All of these have episodes associated with them in the back catalog, if you’re curious; Izumi Shikibu and the Diary of Lady Sarashina were a part of episodes 296-97, and Kagero Nikki and its author were the subject of episode 383.

There is, of course, a lot that could be said about any of these works, all of which are quite interesting–in particular, and I’ve said this before on the podcast, the Sarashina Nikki connected with me in a pretty powerful way back when I was taking some of my first Japan-related coursework in undergrad.

But there’s no way we could meaningfully recount them here–especially since I want to make space to talk about the two titans in the literary room–so I’m just going to note some key features of these works.

First, we know very little about the authors themselves. For Kagero Nikki and Sarashina Nikki, we don’t even know the name of the authors in question–the Kagero Nikki author is known as the Mother of Fujiwara no Michitsuna, and the Sarashina Nikki’s as The Daughter of Sugawara no Takasue.

This is a result of cultural norms imported from where else but imperial China, where women’s roles were considered primarily domestic and so something as intimate as a name was not generally to be shared with outsiders. This in turn meant that women’s names were not usually recorded in public-facing genaelogies (such as the sorts used to prove membership in a noble family)–and thus said names are often lost to time.

Even in the case of Izumi Shikibu, well, that’s not really a name. “Izumi” is the name of the province her husband was a governor, and Shikibu (Master of ceremonies, roughly) was the highest position attained by her father.

Izumi Shikibu is a sort of public-facing pen name, intended to clearly reference who she is without violating those norms around female propriety.

Second, these were from what we can tell intended to be public-facing works, despite the use of the word “diary”–in this case, the diaries in question were intended to public literature rather than a private record or confessional. The nature of the diary genre is complex and more than we can get into here, but particularly by the mid- to late Heian years it was clear that these works were being written with the notion that somebody would see them–that they were a chance to demonstrate literary talents.

Third, all these texts are unified by themes that might be called religious themes derived from Buddhism–notions of worldly impermanence, and especially of one of the most important terms in the history of Japanese literature: mono no aware.

That term is usually rendered in English as “the impermanence of things”; it’s a bit of an anachronism to use it here, because it was not coined until several centuries later, by early Japanese nationalists looking back to the Heian past to discover what they thought was the true essence (or at least a truer essence) of Japanese identity.

These thinkers identified mono no aware as a sort of psychological awareness that everything in the world is ultimately impermanent and will fade away, and a sort of wistful sadness at that thought combined with an exaltation in that very impermanence–which was what gave the world itself meaning. Hellen Craig McCullough’s rough definition of the term was, “a deep but controlled emotional sensitivity, especially to beauty and to the tyranny of time.”

The idea of mono no aware has, ever since those early nationalists coined it, been almost synonymous with the literature of the Heian period. Indeed, it’s sometimes emphasized to the point of being reductive–but still, it’s hard to ignore the presence of this notion in period literature.

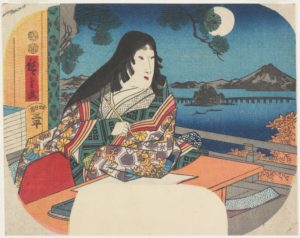

And of course, it’s all the more evident in probably the single most famous text of the entire era: the Genji Monogatari, or Tale of Genji, ascribed to Murasaki Shikibu.

Once again, by the way, that’s a pen name: Murasaki is a title given to her for reasons that are somewhat contested, while Shikibu simply refers to the fact that, much like Izumi Shikibu, her father worked as master of ceremonies within the court. She herself was a Fujiwara, and there’s even been some research suggesting that we can uncover her personal name–but that’s not what most people know her as, so I’m not going to go over it here.

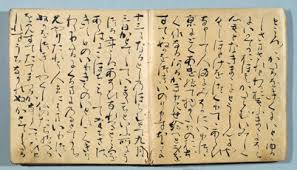

Anyway: the Tale of Genji is far and away the most famous of another genre of Heian literature that was, in its day, extremely dominant: the longform romance, a genre that was apparently particularly popular with aristocratic women–who both could read the texts and were barred from public life, meaning they had a lot of time during the day to fill. Sei Shonagon, about whom we will talk in a second, describes romances as the best cures alongside go and backgammon for boredom, and Takasue’s Daughter (the author of Sarashina Nikki) described romances like Genji as so popular that despite the hundreds of copies in circulation among the women of the capital they were genuinely difficult to get a hold of.

As for what makes Genji specifically special, once again, I’ll turn to McCullough to talk about why Genji in particular stands out because I think she puts it so well: “Murasaki echoes the concerns and adopts some of the techniques of the waka poet, developing two major themes – the tyranny of time and the inescapable sorrow of romantic love – within the context of man’s relationship to nature. But whereas the poet seeks to distill mono no aware into the briefest of lyric expressions, Murasaki uses both poetry and prose to explore the concept in evocative, leisurely detail, weaving a fabric of infinite richness and complexity. Whereas the anthology poet avoids indecorous personalism, Murasaki fills her stage with more than five hundred characters, each a recognizable individual, and makes her long story develop logically from their thoughts and feelings, and from the interplay of their personalities.”

The core of the plot revolves around Prince Genji, an offshoot of the imperial clan pining with love for one of the emperor’s concubines (the lady Fujitsubo) and dealing with a less than ideal marriage to his own wife (the Lady Aoi). As a result, he busily sets out having affairs across the capital, with much of the text being consumed by these various recountings of his amorous entanglements with women (and at least one boy).

The narrative is largely episodic–it’s fairly likely that Murasaki wrote the early chapters (either just before or after the untimely death of her husband), rose to prominence because of them, and then began to receive sponsorship to finish the rest. Specifically, she was taken in as a lady-in-waiting to Empress Shoshi, one of two rival primary wives to Emperor Ichijo. With Shoshi’s sponsorship, she continued to work on the text, finishing it by 1021 (when Takasue’s Daughter references completed manuscripts in her diary).

Genji Monogatari is often held up as not just a classic of Japanese, but of world literature; in its heyday, it was widely circulated both as a manuscript and as an emaki–a version with illustrations of the various scenes attached.

There is, of course, a lot more to say on Genji–but I do also have to note here that, as longtime listeners of the podcast know, I am not a huge fan of this particular text.

No shade to those that are; the episodic style is simply not my thing–and besides, it has fierce competition from my absolute favorite author from this period.

She is, of course, Sei Shonagon, also a pseudonym–Sei coming from a character in her father’s last name, and Shonagon being the Japanese name of the government rank of Junior Counselor, though it’s unclear why this moniker was attached to her as neither her father nor her husband ever served as Shonagon.

Sei Shonagon was also a lady in waiting to Empress Teishi–who was the OTHER primary consort of Emperor Ichijo, creating something of a rivalry between Teishi and Shoshi and between their various retinues, including Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon.

This is partially why our episodes on Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon are back to back in the catalog–episodes 270 and 271, specifically, so that as in life so in death they can rival one another.

Sei Shonagon is best known, of course, for Makura no Soushi, often translated as The Pillowbook of Sei Shonagon–that name being reference to the text serving like a diary, kept by one’s bed to record one’s thoughts.

Still, the Makura no Soushi is emphatically not a diary–it belongs to a distinctly Japanese (and distinctly Heian) genre called zuihitsu. Literally meaning “wandering brush”, zuihitsu are not intended to provide a narrative of one’s life in the style of a diary. Instead, the goal is to record amusing or interesting anecdotes, shorter stories, or just interesting “shower thoughts”, to use a modern turn of phrase.

Basically, think of it like a series of social media posts rather than a coherent narrative.

The text got its start because Sei Shonagon was gifted some paper by Empress Teishi–paper being a luxury item since it had to be hand produced, but the commissioning of a new manuscript of one of the Chinese classics (Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian) meant there was some extra lying around the palace.

Sei Shonagon used this paper to begin composing her musings, supposedly just for her–she was, she claimed, very upset that she’d just so happened to leave her writing out in plain view in her home while away on a trip, and that friends of hers just so happened to come by and find it lying out there and JUST SO HAPPENED to read it and find it funny and take it with them to read more and read with other people and oh no woe is me my secret work is out there!

Obviously the text was always meant for public consumption, as a way for Sei Shonagon to show off what a witty and clever person she was.

And I have to admit, I think it worked. I find Makura no Soushi to be extremely fun, from her anecdotes about a one night stand (ending with annoyance at her lover taking too long to get dressed and beat it), to her advice to religious orders (that they hire hot priests so people will pay attention to what they say) to the things she finds annoying in men: “A man you’ve had to conceal in some unsatisfactory hiding place, who then begins to snore.” / “”A man who has nothing in particular to recommend him discusses all sorts of subjects at random as though he knew everything.”

I find this sort of humor easy to connect with, which probably explains why I prefer Makura no Soshi among all the Heian classics–it helps also that the anecdotal style means the narrative is not as long or complicated as, say, Genji, and thus easier to follow.

This is all, of course, a brief sampling of the classics of Heian literature–as I’ve said, each text we’ve talked about either could be or already is an episode all its own, and even those don’t really do justice to all you could get from them.

That said, I think an overview of the literature of the era is worthwhile, because of what it tells us about the period in general–the importance of public perception as a part of one’s literary persona (be it writing poems or dunking on your lovers in a witty anecdote), the fusion of fashionable Buddhist notions into the literary scene, and of course the central role of women in creating what came to be defined as the classical Japanese corpus of literature.

By far my favorite thing about Heian period literature, however, is how alive it all feels. You can read something like Makura no Soshi or the Sarashina or Kagero Nikki and get a sense of the personality, of the life, of a person who lived 1000 years ago. How cool is that?!

Next week, it’s back to politics, but I hope you’ve enjoyed our foray into the world of more cultural history.