This week: Japan’s empire in Micronesia comes apart under the face of both the miscalculations of military leadership and the contradictions that had haunted it from the jump.

Sources

Peattie, Mark R. Nan’yo: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945.

Hezel, Francis X. Strangers in their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands.

Poyer, Lin. The Typhoon of War: Micronesian Experiences of the Pacific War

Poyer, Lin. “Chuukese Experiences in the Pacific War.” The Journal of Pacific History 43, No 2 (Sept, 2008)

Images

Transcript

It wasn’t really until 1940 that war came directly to Micronesia. Its indirect effects had been felt for years by that point, however. Japan had been involved in conflict for 3 years at that point on the Asian mainland, as part of the long slog of the ‘China Incident’, but outside of an uptick in patriotic exhortations–and an extension of the draft to those Japanese civilians eligible to it–the China war’s main impact on the area was the implementation of rationing protocols to military resources like gas and steel.

Micronesia itself was very much a rear area in the China conflict, and so its mobilization was correspondingly limited. Starting in 1940, as tensions grew worse with the United States, this began to change.

Which actually leads to an important point from the jump. Remember, one of the terms of Japan’s league of nations mandate in Micronesia was an agreement not to militarize the islands with defenses or bases. Both its mandate charter and the treaties signed by the interwar government banned the fortification of the area. In particular, the Five Power Treaty on naval arms limitation, signed in 1922, proclaimed that, “no new fortifications or naval bases shall be established in the territories and possessions specified; that no measures shall be taken to increase the existing naval facilities for the repair and maintenance of naval forces, and that no increase shall be made in the coast defences of the territories and possessions above specified.”

However, the decision by the Nan’yocho to close the islands (outside of a few specific open ports) to foreign shipping led immediately to suspicions in the US Navy that Japan was violating its mandate and treaty obligations and turning the islands into naval fortresses.

In point of fact, from everything we can ascertain, that was not the case. The Nan’yocho carefully followed the fortification ban, and while the Imperial Japanese Navy did have a liaison presence in the area dedicated to surveying islands and making plans for their potential fortification in a crisis, those plans were very much just that–potential ones, to be used only if the situation (in the eyes of the Japanese leadership) warranted it.

The only real military improvements made by the Nan’yocho were mixed use ones, so to speak, like deepening the harbors in Palau and adding drydocks–things that had civilian use, but could also be converted to military ones as needed.

Still, US Navy leaders remained deeply concerned about the potential for Micronesia to be militarized, particularly given that such an action would cut off the American-controlled Philippines and threaten Guam, the two strongest American bastions in the West Pacific. ONI, the American Office of Naval Intelligence, spent a great deal of time and energy trying to ascertain whether a secret program of fortification was, in fact, going on.

The most famous of these was the “undercover” sojourn of Colonel Earl Ellis in the region from July of 1922 to May of 1923. Ellis was a US Marine who had served in Asia for a time before eventually being attached to the Marine Corp’s Intelligence division. There, he sold his superiors on a plan to infiltrate Japanese Micronesia and there make topographical and hydrographical maps of the region to be used if Japan and the US ever went to war–and along the way, he’d keep a lookout for any Japanese violations of the non-fortification agreements.

Now, I imagine a few of you might be thinking–wait, isn’t this man the worst spy imaginable? As the name “Earl Ellis” gives away, he’s about as white as they come, after all, in a region dominated by people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent. Wouldn’t he stand out like a sore thumb?

Well, you’re right, that probably would be the biggest problem with this plan–except it wasn’t, because Ellis was also a raging alcoholic who spent a good chunk of his sojourn through the region drunk out of his mind.

He also kept his notes totally unciphered, so when the Nan’yocho police started tailing him (which they did almost immediately), it did not take them long to figure out who he was (though they did not arrest him for fear of a diplomatic incident).

Ultimately, Ellis’s mission would end when he got so drunk in Palau–at one point then blabbing to his fellow bargoers about his mission–that he then took ill, dying shortly thereafter from complications of alcohol poisoning. His terrain surveys did prove useful down the line, but they also made the Nan’yocho leadership way more paranoid about American intentions in the region and served to ratchet up the mistrust even further.

Stories like Ellis’s drive home the extent of the mistrust even at this early stage between Japanese and American military leadership–after Ellis’s little misadventure, the Imperial Japanese Navy became far more paranoid about American presence in the area, even in ostensibly civilian forms like scientists or merchants. All, they assumed, were part of an advance guard of Americans reconning the area in preparation for a future attack. On the American side, that paranoia about Americans simply reinforced the assumption that Japan was violating its agreements and fortifying the area–why else would they behave like they had something to hide?

In reality, though, Japan did follow its mandate agreements, as we’ve said–at least, until 1939. By 1939, Japan had withdrawn from the League of Nations and all its arms limitation treaties–more importantly, tensions with the US were being inflamed by Japan’s horrific acts in China and by the growing closeness of the Japanese military leadership to the regime of Nazi Germany. Increasingly, leaders on both sides assumed war was inevitable.

Up until 1939, the Imperial Japanese Navy took a fairly limited role in the region. Outside of its liaison office attached to the Nan’yocho central government in Koror, on Palau Island, the navy had no official presence in the region.

It had consulted on some of the harbor expansions and improvements made in Micronesia (especially the Marianas, the heart of the Japanese presence in the area), and on some of the improvements to airfields and communication lines made during the mid-1930s. But these were always collaborative efforts with the Nan’yocho, and ones that had (ostensibly) civilian uses.

In 1939, the Navy dropped all pretense and began to take a direct hand in the region. In that year, the Fourth Fleet–outfitted primarily for naval construction–was dispatched to Micronesia to begin a program of fortification intended to serve Japan’s goals in the region in the event of war.

What were those? Well, this is where we get a bit into the changing face of war on the sea at the time.

As I mentioned a few episodes back, Micronesia was not actually that helpful as a base area by the standards of traditional naval doctrine before World War II. Those doctrines focused on the primacy of the battleship, which could blow any other ship away with its mighty guns.

To protect those ships, the thinking went, a fortress island should have deep, easily fortified harbors to shelter and repair ships–which should butt up against difficult terrain like cliffs or jungle that could help protect a bunch of shore batteries. Thus, you could create this little fortress area from which battleships could range out, attack the enemy, and then fall back to as an easily defensible base.

This was the orthodoxy of the imperial navy, but unfortunately Micronesia was poorly suited for it. Only Truk really matched the specifications for this kind of fortification; most other islands did not have deep enough harbors or the terrain was just a few feet above sea level and hard to fortify.

However, a different wing of the navy saw a very different kind of potential in Micronesia, thanks to the advent of a powerful new tool–naval aviation.

The interwar period, as it’s called, is the time where some naval thinkers began to realize that the advent of aviation, and especially the aircraft carrier, had rendered traditional battleships kind of obsolete. After all, all those powerful long range battleship guns were impressive and the ships look very badass, but none of those guns are ever going to outrange a squadron of bombers launched from a carrier. More broadly, coastal defense guns on a fortified island can control a lot less space, so to speak, than a wing of long-range bombers stationed on an airfield atop that island can.

Adherents to this aircraft-centric approach to naval war, however, were on the outs in the upper levels of Navy leadership–most of the upper levels of command remained firm believers in the traditionalistic battleship approach, which after all had been good enough to win last time Japan had fought in a big naval conflict against Russia in 1905. So why shouldn’t it be good enough now?

This division within the Navy, combined with the fact that Japan actually did maintain its commitments against fortification in the region until fairly late in the game, meant that military preparations in Micronesia could best be characterized as haphazard.

Members of the ‘aircraft faction’ were able to push through construction of some impressive airfields on Roi in the Kwajalein Atoll, Taroa in the Maloelap Atoll, and on the Wotje atoll. Truk was also substantially fortified along the lines of a traditional ‘fortress island.’

But the fortification effort was still only partially completed by late 1941–the Marshall Islands, for example, were practically unfortified by late 1941. And then it was too late–in December, 1941, Japan and the US finally came to blows.

Now, if you were an observer on Truk or Palau or one of the other islands of the region, your first inclination would probably be to say that the partial completion of the fortifications didn’t really matter.

In the final months before Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Navy had moved large numbers of men, ships, and planes into the region–at the same time the Pearl Harbor attack began, those forces went into motion. An invasion force stationed in the Bonin islands sailed on to Guam; a wing of bombers stationed on Saipan made way for the Philippines; from Kwajalein atoll, another wing of bombers set off for Wake Island, followed by an amphibious attack force; from Jaliut, another amphibious attack force set off for the Gilbert Islands.

In all of these efforts, success came swiftly–the only substantial resistance came from the US Marines on Wake Island, who held out for two weeks before surrendering.

Success, simply put, seemed to be in the offing–Micronesia had served the purpose the navy had always wanted it for, as a strategic grounds for expanding Japan’s military reach in the Pacific.

Except, of course, that’s not quite how it went down in the longer term. The whole assumption behind the massive surprise attack was that it would sap America’s will to fight a long war. Even if it didn’t, when the Americans inevitably launched a massive counterattack with their combined Pacific Fleet, the Japanese could meet it and destroy it with a single blow, forcing the Americans to the peace table.

Except, of course, none of this worked out the way it was supposed to. The Americans didn’t come to the peace table, nor did that massive combined counterattack ever come–instead, the American fleet split up, operating in smaller divided forces to first stop the Japanese advance and then begin driving it back. And here, the many problems of war preparation in Micronesia began to show themselves.

First and foremost, the war itself was not only not something that Micronesians themselves bought into–high-minded rhetoric about ‘liberating Asia’ notwithstanding–but actively served to perpetuate the clear gulf between themselves and their Japanese occupiers.

For example, much of that prewar rapid construction buildup was done, not with Japanese labor, but by Micronesians conscripted to serve in labor battalions. The Nan’yocho did not have much in the way of mechanized construction equipment (to be fair, in general Japan’s construction industry was woefully unmechanized in general at this point compared to the US), and the only help the Imperial Japanese Navy offered was the construction forces of the Fourth Fleet–not much to cover over 2000 islands.

The central government in Tokyo was not much help. The Justice Ministry did offer a few thousand convicts from prisons in the Tokyo area, particularly the Yokohama Central Prison–thousands were shipped off to the Nan’yo to great celebration and fanfare, complete with patriotic speeches enjoining the convicts lined up on the docks to prove their redemption by sacrificing for the homeland. The group were even given a fancy name–the Sekiseitai, or Sincerity Battalions.

All that sincerity didn’t help them much when they came to Micronesia to do forced labor building defenses and airstrips; on Tinian, 20 out of the 1200 men assigned to work on a new airfield died of heatstroke, and hundreds more suffered severe health problems from the appalling conditions and severe work demands.

The Nanyocho also relied on labor from Korea, and on deals with companies like Nanyo Kohatsu that offered some of their employees for the construction process. But even this was not sufficient for the navy’s demands, and so most of the labor fell on Micronesians themselves, who were conscripted in massive numbers by the Nan’yocho and the Navy, relocated to other regions, and forced to labor on the defenses of the region.

Sometimes, the conscription was done with a lighter hand; on Truk, the same Mori Koben who once upon a time had fought beside local chiefs and run the small Japanese trading outpost on the island still had quite a following, and was able to convince enough young men to sign up for labor for the Nan’yocho that nobody had to be forced into it. But that was the exception, not the rule–in many cases, Micronesian men were simply rounded up by the police like prisoners.

This did not, as you might imagine, endear them very much to Japanese rule–particularly given the many other issues of Nan’yocho rule we’ve already talked about.

To use the words of Parang Nomono, a native of Truk who was conscripted to help build up the island’s defenses and who spoke to academics about the experience decades later: “At that time, some Japanese were bad; new Japanese replaced those of the previous government. They were our bosses and were very tough on us. They often beat us with metal, or anything they had. Work got harder, just the opposite of our previous jobs. We were told to work hard because it was for the war, and if we don’t they will beat us because it’s also for their Japanese leader, Tenno Heika [the Emperor] that all these things or work should be accomplished. We worked days and nights.” Nor was he alone in that experience; Taru Ounuwa, another native of Truk, had a similar experience: “We no longer had Sundays. Every day was a weekday. We didn’t do our own work; we just worked for the government, clearing areas for soldiers’ buildings, putting up their houses. When they came, they would check out a place, see if it was a good spot,and assign us to clear it, because that’s where they were going to put up buildings for the soldiers’ supplies. We were surprised when they just came and moved us from our places; we said, “What’s happening? Why are they doing this, asking us to make this place, but without announcing it or talking to us first?”

Both he and others also recalled that beyond forced labor, many were forced to give up their homes–just as Nan’yo Kohatsu had done in the Marianas to build the sugarcane industry. This time, however, they were being dispossessed to make room for new military facilities and the support staff to run them.

To make matters worse, in cases where conscripts were moved from one island to another the Japanese simply left Micronesians who’d been relocated on the islands they’d been taken to rather than shipping them back home, claiming the capacity was needed for war related reasons. Many of these conscripted laborers didn’t even make their way home until the war ended half a decade later–if they did at all.

There were a few Micronesians who were by this point true believers in the Japanese cause, primarily those who had been young children at the time of the start of the occupation and who had joined the Seinendan, the young men’s associations, as a result. These were some of the only successful attempts at propagandizing to Micronesians about the benefits of the ‘glorious rule’ of Japan’s emperor, primarily because they involved a lot of things that make young men excited–hosting social events and marching around in vaguely military uniforms singing songs.

So it’s not that surprising that most of the Micronesians who actually volunteered for service in the war were former Seinendan participants. They were organized into volunteer detachments (Teishintai in Japanese) led by Japanese officers, often retired military types who served in the Nan’yocho government or who had settled in the region. Pointedly, they were not allowed to serve in either the army or navy; the navy never took non-Japanese sailors, and the army barely got around to taking Korean and Taiwanese conscripts by the end of the war, with Micronesians seen as far too lacking in “East Asian spirit” to even be considered.

The history of these few groups who actually did care about the Japanese empire demonstrates, quite frankly, why so few Micronesians ever felt that way. They were treated as fundamentally disposable and unimportant.

Teishintai units were deployed in 1942 and 1943 in the fighting along the southern edge of the empire, in places like Rabaul and New Guinea. There, they were given support duties as laborers–and often split up from each other and assigned to different Japanese units. Given that again, if they were lucky, these young men had gotten five years of Japanese language education tops, one has to imagine it was a somewhat isolating experience.

And then of course there was the actual fighting, during the course of which Teishintai units took enormous casualties. One unit, sent from Ponape to Gona in eastern Guinea, lost all but 3 of its members. Even after the fighting, teishintai units were treated as an afterthought. The 104th Construction Detachment, a volunteer unit sent to Guinea, was left behind once Japanese forces evacuated–its Japanese commander killed himself, and they were abandoned on the island without any supplies.

It would take the members of the 104th 10 years to arrange a way home for themselves–and to add insult to injury, none were ever paid the salaries promised them by the army ministry as a part of their ‘glorious’ labors for the empire.

The war, simply put, served to further alienate Micronesians from Japan–a process, to be fair, that had already been well underway by that point. And then, as the war situation turned worse, even more problems were revealed.

By 1943, Japan had changed its strategy once again; now, it would attempt to set up a defense perimeter in its existing territory and hold the line in preparation for renewed offensives by 1944. Micronesia was at the front end of that perimeter–the navy’s massive combined fleet, based on the heavily fortified island of Truk and led by the great battleship Yamato, was tasked with ensuring the Americans did not make any headway into the empire’s territory.

But the navy leadership, it turned out, had massively misjudged the value of Micronesia as a military bastion in the Pacific. Truk was one of very few islands with substantial fortifications, and the combined fleet rarely ventured away from it–even after repeated requests that the Yamato and other battleships be dispatched to the frontlines for fire support for embattled Japanese troops.

Naval leadership was too hesitant to risk its fleet for anything other than the decisive final battle, which the Americans were never really willing to give them by massing up their whole fleet too. So instead, the combined fleet simply sat at Truk well into 1943, with the crews of its great warships focused primarily on looking spiffy in uniform and enjoying the many pleasures of shore leave–including the extension into Micronesia of Japan’s native system of licensed brothels.

Meanwhile, the other islands of Micronesia had their smattering of military airfields, but these proved less useful on defense than had been hoped. Particularly after the disastrous Battle of Midway in 1942, when Japan’s navy lost several of its carriers in a decisive defeat by the US, America had command of the skies–and the few airplanes those fields could muster were wiped out one at a time as Allied warplanes simply picked them off one at a time.

And that’s when the Japanese could actually get their planes into the sky, which proved increasingly hard to do because of another key American tactic: the use of submarines.

The Imperial Navy had largely neglected submarines, both for itself and in terms of anti-submarine countermeasures. It was far more concerned with decisive surface engagements. The United States, by comparison, devoted a great deal of time and energy to submarine warfare.

And it turns out, if you can’t get things like food and medicine to your island garrisons, or airplane fuel to your remote aerial outposts, because the US Navy keeps sinking all your ships, well, that’s a bit of a problem.

Indeed, more than a bit of a problem; by the end of the war, the US Navy alone had sank 58% of Japan’s total merchant marine (the fleet of vessels responsible for logistics), and the Royal Navy and various commonwealth navies had taken down even more.

Without food or gas, or even the ability to successfully redeploy troops to areas under new threat, the island garrisons of Micronesia became less ‘defensive bastions’ and more ready made target galleries for the Americans whenever they got around to it.

From this point on, the history of Japanese-occupied Micronesia becomes, frankly, rather repetitive. Once their submarine and aerial superiority was assured, the Americans began a strategy of island hopping–attacking the islands they needed as advance outposts to push deeper into Japanese territory, and bypassing the ones they did not.

And frankly, there was very little that the Japanese military could do about this; they couldn’t reshuffle troops to areas that were under threat because their transports kept getting torpedoed, and the constant attacks on merchant shipping made it hard to get enough aviation fuel to even keep basic patrols going, let alone send aerial reinforcements to a beleaguered island or try to ‘win back the skies.’

Realistically, the ‘strategic bastion’ of Micronesia was successful in delaying the American advance into the Pacific and prolonging the war, but not much more than that. Instead, the defenses of the region were slowly rolled up by the American advance, which swept west through the Gilberts (taking Tarawa and Makin atolls), and then the Marshalls (where they landed on Kwajalein and Eniwetok). In each of these cases, American forces swiftly overran Japanese defenses on the coral atolls, whose flat nature made them hard to fortify–particularly as American planes bombed them in advance of the landings.

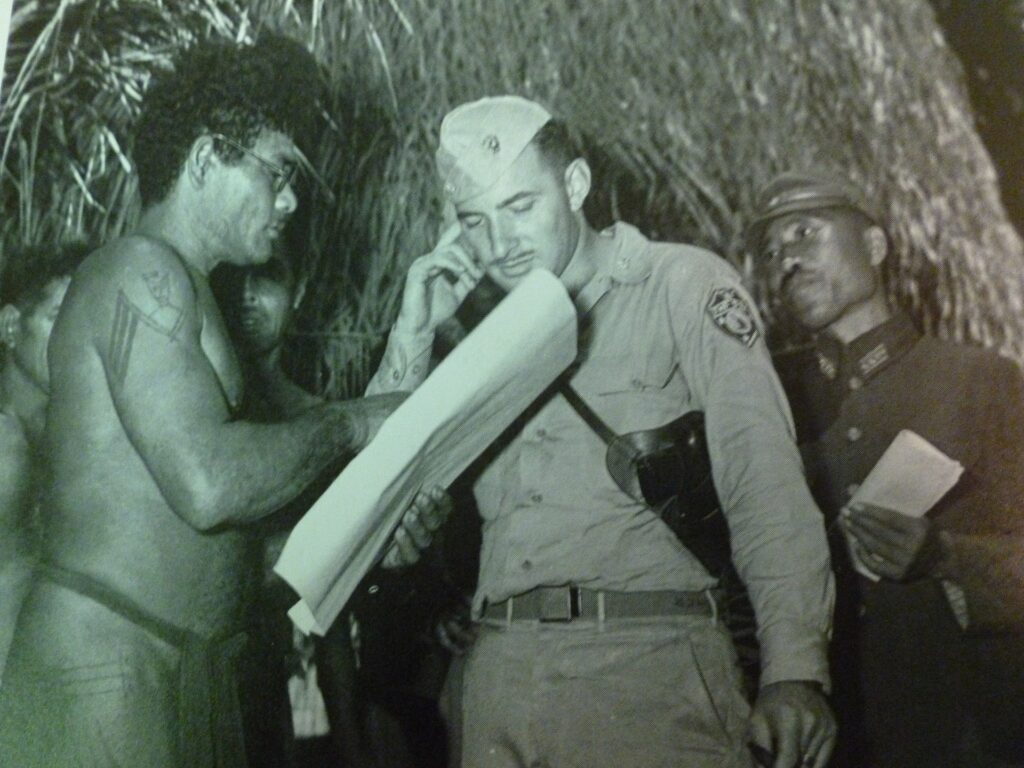

In many of these cases, the Americans were assisted in their knowledge of the local defenses (such as they were) by defections of Micronesian laborers–Japanese records make regular references to the rachi, or kidnapping, of Micronesians by Americans, but it’s pretty clear that these were very voluntary abductions, so to speak.

Which, after all, makes sense–one has to imagine that a Micronesian dragged off to the opposite end of Micronesia to do forced labor under grueling conditions digging up antitank trenches or laying down razor wire or what have you would not feel much in the way of burning loyalty to the empire that sent him there.

This was particularly the case because as the war situation worsened, tensions between the imperial military–which by this point had functionally shut down the Nan’yocho and declared martial law in the region–and the locals grew ever worse. The navy commanders on scene (and eventually army ones sent to reinforce them) commandeered everything they saw as necessary for the defense of the area, without much in the way of sensitivity to the needs of Micronesians themselves. The locals were often given lower priority for what food, water, medicine and such was available–and tempers ran high as a result. Several Japanese garrison commanders appear to have unilaterally ordered the execution of Micronesians they suspected of ‘betraying’ the cause, either by talking to the Americans or taking supplies they needed to live–or simply for insufficient zeal for the cause. It’s hard to get a sense of how many died, however, given the lack of documentation and the wholesale destruction of what records there were by Japanese commanders toward the end of the war.

That’s not to say, however, that Americans were welcomed with open arms. In pretty much every theater of war in WWII, the United States followed a doctrine of massive firepower–basically, using its superior industrial base to build a boatload of bombs, artillery shells, and the like, and blasting the hell out of a place before they attacked it. This was certainly effective at clearing a path forward for American troops, but it also resulted in a great many casualties among Micronesians caught in the crossfire.

Chris Perez Howard, a native of Guam born in 1940 (son of an American father and a Guamanian Chamorro mother), described the results in his novel Mariquita: A Tragedy of Guam: “The sadness I feel for those who suffered injustice at the hands of the Japanese is deep, but I do not hate. The wanton bombing of the island by the Americans, especially the city of Agana, which had to be bulldozed to restore any semblance of order, to the extent that the old Spanish bridge now only points to where a river once existed, is to me equally unjust.”

Similarly, here’s the recollection of Ichios Eas, a native of Truk: “But what I remember most from the war, the hardship, the hard life, the difficulties we faced during the war ? being scared, the Japanese being harsh/cruel, of starving and suffering. I don’t understand why we had to do that, why we had to go through that ? it wasn’t us going to war. When I think back, that’s what I remember the most. Especially the bombs. When the noise coming from the war was so loud we could hear it on another island. Not only that, but those things that light up the sky or the whole island, it was like daylight during nighttime, you could see everything. That was the most scary, during nighttime. Where are we going to run to? Where are we going to hide? The Americans lit up the whole island, even in the dark and in the forest, we could see each other as though it was daytime.”

Interestingly, many of the Micronesian accounts I found expressed a great deal of pity for Japanese civilians; a noble, but perhaps unsurprising sentiment, given that military planners did not exactly show a great deal of care for the fate of civilians either (as pretty much every episode we’ve ever done on the Pacific War demonstrates).

Early in the war there were attempts to evacuate Japanese subjects from Micronesia and away from the fighting, but these proved both haphazard and fraught with plenty of danger given the nature of American submarine warfare in the Pacific.

For example, at the start of the war there were about 43,000 Japanese civilians in the Marianas islands. By the start of 1944 that number was down to about 20,000, but attempts to continue the evacuation proved challenging. One convoy of civilian evacuees in March of 1944 had not even left the sight of Saipan before coming under submarine attack and losing 3 ships.

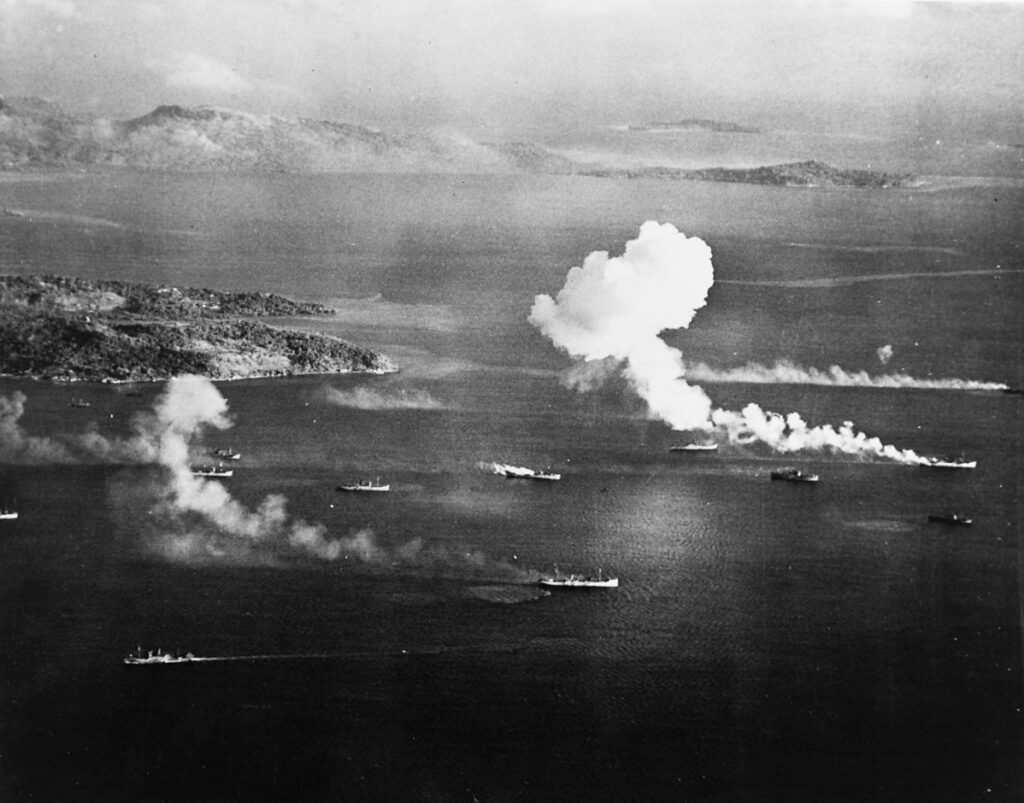

Ultimately, this was how Japanese rule in Micronesia came apart–slowly but, given the military situation, inevitably, the signs of Japanese presence began to vanish. In February, 1944, Truk, the ‘fortress island’ that was sometimes described as the Gibraltar of the Pacific, was blasted to smithereens by Allied bombers in Operation Hailstone. The Allies never even bothered occupying the island itself after destroying its defenses, drydocks, and runways.

Koror city on the island of Palau, once home to the Nan’yocho government offices, was similarly rendered uninhabitable by Allied bombs in advance of an American move into the region in Fall of 1944. The tattered remnants of the Nan’yocho, by this point little more than an appendage to the military government of the area, were relocated to Aimeliik on the west end of the island, but functionally there was little for them to do.

The islands of Saipan and Tinian, once the beating hearts of the Japanese economic presence in the area, were reduced to uninhabitable smoking ruins, the sugarcane fields scorched to the ground.

The war, of course, finally ended in 1945, with the Nan’yo consisting of nothing more than islands which had fallen to the Americans or which housed starving garrisons cut off from the homeland. It took until December of 1947 to ship all the Japanese in the area still remaining at wars end back home.

Today, there’s not much left in terms of physical remnants of the Japanese presence on Micronesia. Much of the infrastructure built in those days was blown to pieces by the Americans–and what survived, like the Shinto shrine on Koror, was taken down to help rebuild the islands. Today, the “Nan’yo” area is home to a host of different countries like Kiribati, Palau, and the Federated States of Micronesia–and, of course, to US territories like Guam.

But Japan is not gone from the region–starting in the 1970s, and with the support of businessmen who had 30 years earlier operated in the islands, Japanese economic interests began to return to the area. These days, it’s mostly tourism (though fishing also remains big business); the Federated States of Micronesia also gets a good amount of money from Japan in overseas development aid.

There are other, more visible remnants of the old relationship as well, in the form of Micronesians with Japanese ancestry–including the children of men like Mori Koben, who remained on Truk until his death just a week after the end of WWII. The first president of the Federated States of Micronesia, for example, was Tosiwo Nakayama, who as the last name gives away had a Japanese father.

Ultimately, what can we make of this interlude in Japanese history? Well, in a lot of ways, I think the “Nan’yo interlude”, so to speak, highlights both the most distinctive ideologies of Japanese imperialism–its pan-Asian rhetoric, its emphasis on Japanese racial superiority, its militaristic justification–and the fundamental contradictions of those ideas.

Just as much, maybe even moreso, than in Korea and Taiwan, the rhetoric that Japan was in Micronesia to “help” was so completely belied by actual policy, which was intended to reduce Micronesians to dependent appendages of the empire. It’s an important reminder, simply put, not to unquestioningly accept the rhetoric of colonialism, but always to question it. Otherwise, we risk replicating the same viewpoints that justified empire in the first place.