This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: “closed country” isn’t quite the full story. How did Japan maintain its connections to the outside world during the Edo Period? And how do some of those connections, particularly in the Ryukyus and Hokkaido, lay the groundwork for future imperial expansion?

Sources

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan.

Walker, Brett L. The Conquest of Ainu Lands; Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590-1800.

Kerr, George H. Okinawa: The History of an Island People.

Elisonas, Jurgis. “The Inseparable Trinity: Japan’s Relations with China and Korea” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol IV: Early Modern Japan.

Images

Transcript

This week, I want to talk a bit about Japan’s connections to the rest of the world during the Edo period. Which might seem like an oddly specific topic on its face, because don’t we know the answer already? We talked two weeks ago about the closed borders of the sakoku policy and the restrictions on overseas travel and trade–what more is there to say about the outside world? And this is commonly the message you get about Tokugawa Japan: it was isolated, cut off from the world at large.

And that’s not fundamentally wrong–certainly, compared to the 1500s, and certainly to post-feudal Japan, Edo-era Japan was far more isolated from the rest of the world. But isolation is not the full story either.

Which is why taking some time to talk about the ways in which a connection to the outside world was maintained is so important–because in reality, there were still some lines of communication open, and particularly as feudalism came to an end those continued connections would become extremely important for shaping what came next.

But first, we should probably refresh ourselves on what exactly Tokugawa foreign policy looked like.

One of the most iconic elements of the Tokugawa shogunate was the so-called sakoku, or closed country policy. In reality, this was less a singular policy and more a series of discrete edicts from the early years of the shogunate–for example, the 1614 decision by Tokugawa Ieyasu to ban Christian missionaries (particularly the Jesuits of Nagasaki), and the 1635 ban by the third shogun Iemitsu on all forms of Christianity within Japanese territory.

Collectively, these laws had the effect of a) shutting down all trade with European nations outside of the Netherlands, b) confining the Dutch specifically to a single trading outpost on Nagasaki and c) forbidding the construction of deep ocean vessels in Japan, and banning all Japanese people from leaving the country.

The aims of these policies should be understood in relation to the wider aim of the shogunate itself. From its inception, the Tokugawa shogunate was a system built on the idea of political stability, with the goal of producing a fixed political and social equilibrium (with the shogunate and its supporters on top) that could be maintained indefinitely. The goal of the closed country policies was simply to maintain this equilibrium; Westerners, and especially Christianity, were seen as a threat to it.

In part, this was because of word reaching Japan of the behavior of Catholic empires in the Americas, where the church was at the forefront of Spanish and Portuguese colonial conquests and enslavement. In part, it was because Christianity itself was perceived as fundamentally subversive, with its emphasis on loyalty to the faith above any other authority–Japan had a long history with militant religion before the introduction of Christianity, and it didn’t take much imagination to see how Christianity itself could lead to an even more dangerous forceful challenge to the existing order.

Finally, European trade was valuable and lucrative–the closed country policy ensured that the shogunate, which controlled Nagasaki directly, had a monopoly on this valuable source of information and income.

Of course, the “closed country” was not ever fully closed. The Dutch, as we’ve established, were allowed to continue trading under the auspices of the VOC-the Dutch East India Company, which controlled a colonial outpost in what’s now Indonesia and dispatched annual trade missions to Nagasaki from their primary fortress at Batavia (now Jakarta).

Merchants from China were also free to come to Nagasaki without restriction on the Japanese side–in doing so, they were technically breaking Chinese law, which forbade trade with Japan since it was not a tributary state of China’s emperor, but smuggling in this way was good money so there were plenty of people willing to chance it (and, it turned out, plenty of Chinese officials willing to bankroll said smuggling in exchange for a cut of the profits). Envoys and merchants from Korea also regularly came to Japan, and would not have seen the country as closed in any meaningful sense of that word.

The Korean case is particularly interesting. In 1609, Tokugawa Ieyasu set up a treaty of peace with Korea ending formally the hostilities of Hideyoshi’s invasion. Both sides also set up a trade network running through the Japanese-controlled island of Tsushima (where the daimyo of the So clan was entrusted with managing Korean relations) to Korea’s coastal ports, most notably Busan.

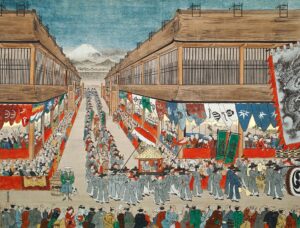

Yearly trade continued apace throughout the Edo period, and the Korean monarchs of the Joseon dynasty dispatched no less than 12 embassies to Edo over the course of the Tokugawa years–usually to mark the ascension of a new shogun. These embassies were a BIG deal, with 300-500 participants. Those participants were in turn handpicked; the diary of one embassy member from 1764 describes all participants being interviewed personally by Korea’s king, who had them compose poetry under a time limit to make sure they’d be able to hold their own and impress their Japanese hosts.

And to their credit they usually did; one of the most famous Japanese scholars of the period, Arai Hakuseki, would later recall as one of the proudest moments of his early career having the Korean leaders of an embassy remark favorably upon his poetry–one of them even wrote a foreword for it.

And it wasn’t just nerds like Arai who were excited to meet the Koreans. Sin Yu-han, who visited Japan in 1719 to congratulate the new shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune, described being virtually mobbed in Osaka as, “a rush of people wanted to have my poetry; they piled papers on my desk to ask me to write something, and although I wrote for everyone who asked the papers continued to pile up like firewood….sometimes I could not sleep until dawn, or I was kept from eating, by these people. Japanese respect our writing as though we were gods, and keep them as treasure. Even a miserable palanquin bearer is happy to have a Chinese character written on a piece of paper by a Korean envoy.”

If you’re wondering, Sin was not equally impressed with the Japanese as they apparently were with him; in particular, he was deeply disturbed by the rarity of formal reverence for Confucius. Confucian temples honoring the great sage are common in Korea and China, but Confucius worship (just like Confucius himself) never developed as big a following in Japan as it did on the mainland.

He did however remark at the material prosperity of Osaka and especially Edo, as well as the numerous villages he visited along the way. A true Confucian, he expressed disdain at all this distracting material wealth, but was forced to admit that Japan’s people appeared to be well off.

One might be tempted to conclude here that relations were friendly between the two powers, but that would be a bit disingenuous. And I’ll quote here from Marius Jansen’s epic The Making of Modern Japan: “. Sin Yu-han recorded a conversation with Amenomori Hoshu in which each complained about the other’s view of his country. We have been friendly with Korea for some time, Amenomori said, but Korean books still refer to us as pirates; how can this be? Well, said Sin, those books were probably written after the Japanese invasion of Korea, so it’s quite understandable. Still, how is it that Japanese refer to us as Tojin (Chinaman)? Well, responded Amenomori, by law we are supposed to call you Chosenjin (Koreans). But because of your similarity to Chinese, we usually call you Tojin; this means that we respect your culture. Unfortunately, Amenomori was disingenuous, for Tojin had become a generic term for foreigner, which ordinary Japanese applied even to Westerners. Worse still, only a few years before this the diary of the Dutch mission head in Nagasaki notes of a summer day that “this day commemorates their victory over the Koreans, whose country they turned into a tributary nation.” In other words, in Nagasaki the Japanese were explaining to the Dutch that they were celebrating Hideyoshi’s “victory” over the Koreans and that Korean missions were those of a tributary state.”

Beyond Korea, of course, there was Okinawa, specifically the Ryukyuan kingdom. That kingdom has its own fascinating history that is frankly more than we can really get into here; simply put, the kingdom emerged in the 1400s when a man named Sho Hashi was able to unify the warring kingdoms of the largest island of the Ryukyuan archipelago, Okinawa. His descendants would reign over a unified kingdom of seafaring merchants at the center of one of the Western Pacific’s major trade hubs.

In particular, the Ryukyus became something of a clearinghouse of Chinese goods thanks to limitations on maritime trade put in place by Chinese emperors (who considered overseas trade socially disruptive and therefore something to be limited). This position made the Ryukyus quite wealthy; it also made them a melting pot of cultures. For example, the administration of the Sho kings was patterned off of that of imperial China and governed by a similar elite of scholar-aristocrats, with some Ryukyuan scholars even receiving permission to study in Beijing’s great imperial academies. However, the elite of this kingdom also wore two swords on their hips in the fashion of elite members of Japan’s samurai class.

By the late 1500s the prosperity of the kingdom would begin to decline thanks to competition from the Portuguese, and in the 1600s the kingdom was truly brought low. In 1606, Tokugawa Ieyasu himself authorized a punitive expedition to seize the islands of the Ryukyus.

Why would he do this, when in other arenas–like the disastrous war in Korea–he had shown a desire to avoid military expansion rather than embrace it?

Well, partially of course it was a matter of power differential–while war is never a sure thing, the relative power imbalance between Japan and the Ryukyuan Kingdom was substantially greater than that between Japan and Korea.

The Ryukyuan monarchy had also engaged in several diplomatic slights against the new shogunate; the Ryukyuan king Sho Nei had repeatedly refused Ieyasu’s requests for aid in re-establishing relations with the Ming dynasty (which had been broken off during Hideyoshi’s invasion) and for a Ryukyuan envoy to come recognize Ieyasu as the new ruler of Japan.

Such things could not be allowed to stand, of course–they would reflect poorly on the prestige of the Tokugawa house.

The invasion took three years to come together, and given the challenges involved in an overseas invasion the onus fell onto the nearest feudal domain: Satsuma, the remote but wealthy southern outpost of the Shimazu family.

The Shimazu had been hostile to Ieyasu before his rise, but had accommodated themselves to his new regime after Sekigahara, and besides: on the Japanese side, the invasion was a win-win, so why not go along?

When the attack finally materialized, it was frankly something of an anticlimax. The island kingdom’s defenses were swiftly overrun, and King Sho Nei agreed to come to terms with the invaders.

The resulting treaty saw the Ryukyuan kingdom become a tributary of Satsuma domain–and thus indirectly the Tokugawa shogunate. The kingdom was also forced to give up several of its northern islands to Satsuma–collectively, they are known as the Satsunan islands (literally “south of Satsuma”) and remain a part of Kagoshima Prefecture rather than Okinawa today.

Those islands were largely converted into sugar plantations to fuel Satsuma’s economy, run a brutal regime of forced labor.

The Ryukyuan kings, meanwhile, were forced to pay regular tribute to Satsuma (which in turn forwarded some of the cash to Edo) and to send annual missions to the Satsuma domain castle town of Kagoshima to demonstrate their subservience. They were also responsible for implementing Japanese policies like the closed country edict and the Christian ban.

However, there was one interesting hiccup to all this–the Kings of the Ryukyus were also ordered to maintain their status as a tributary state first of China’s Ming dynasty and then to its successor (which overthrew the Ming during the 1600s), the Qing.

But wait, I hear you asking, how is it possible for one kingdom to be a vassal of two different states–and why would Satsuma domain or the shogunate want that? Well, it’s important to remember two things here. First, tributary status to imperial China was in practice not particularly demanding; you had to send missions every so often to show your submission (while also engaging in trade), call your ruler a king rather than an emperor, and acknowledge the nominal overlordship of China’s emperor. But the Chinese emperors did not intervene that much in the policies of tributary kingdoms; in practice, this was more symbolic than anything else.

Plus, and this is really important: trade with China was valuable. Like, seriously valuable. Even though coinage was no longer the commodity it once was–the Tokugawa shogunate was the first government in centuries to succeed in creating something approximating a national currency system, though that system remained a bit messy and confusing–there were a LOT of other things people in Japan wanted to buy from China.

And legally, they couldn’t; Japan wasn’t a tributary state, and thus couldn’t engage in legal trade with China. There were quite a few Chinese smugglers who were willing to brave legal troubles back home in the name of profit, but even so never enough to match demand (which was why the goods they brought were so valuable).

So on the Japanese side, a vassal state that could legally engage in trade with China was worth quite a bit–so much, in fact, that Satsuma domain issued a regulation that nobody in the Ryukyus should learn Japanese (so that Chinese envoys visiting the islands would not be suspicious about their relationship to Japan).

But surely, I hear you wondering, the Chinese would notice something was up, right? Well, there’s ample evidence to suggest that yes, they were in point of fact totally aware of what was going on–but chose not to make an issue of it.

Once again, we’re left asking ourselves why. And the answer appears, based on what we can find in the record, to be a matter of cold, hard cash. Ostensibly China’s rulers were a class of Confucian nobles educated in the values of the great sage, which included rejecting acquisitiveness and materialism in favor of personal virtue. But practically, well, Confucian virtue didn’t pay the bills–and so there’s a lot of evidence that officials in both the Ming and Qing dynasty chose to look the other way about the Ryukyuan situation and in fact helped bankroll the indirect trade with Japan through the islands. After all, they were aware of how valuable the trade was–so why not profit off it?

The other place we should turn our attention to for a moment is Hokkaido–though using that name during this period is an anachronism.

You see, in the 26 episodes we’ve done so far, I’ve been referring to three main Japanese islands–Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, plus a smattering of others. But these days, we say there are four home islands–so how did Hokkaido become one of them?

Well, to answer that question we have to once again talk a bit of background context, specifically around the aboriginal people of Hokkaido, the Ainu.

And by the by, the Japanese name for the island at this time would have been Ezo or Ezochi, but I’m going to stick to Hokkaido even though it’s anachronistic simply because more people are likely to know what I mean by that, and in my experience when talking geography in an audio medium it’s best to be as clear as possible.

Anyway: the Ainu are often posited as related to a group that came up in our discussions of early Japanese history, the Emishi. These are the so-called “shrimp barbarians” whose defense of their homelands in northern Honshu led to a multi-century conflict with the court of Japan’s emperors, who in turn created the samurai class to fight that war.

The Emishi, you might recall, were largely subjugated by around 1000 CE, with the conquests of the imperial court extending all the way to the northern tip of Honshu and the straits of Tsugaru separating it from Hokkaido.

It’s often theorized that some part of the Emishi population retreated to Hokkaido and became the Ainu–or alternatively that the Emishi and Ainu were related populations that branched off from each other due to geographic isolation. But there’s no way to know for sure; sociological and archaeological studies of the Ainu have found a lot of similarities with the indigenous populations of the Russian Far East and Siberia, so it’s possible the Ainu migrated to the region from those areas independently.

Regardless: the Ainu lands on Hokkaido were at this point considered too remote for first the emperors and their regents and then the first two shogunates to bother with directly. Instead, they empowered a local clan, the Ando–possibly descended from Emishi who had culturally assimilated, though the truth of that story is debated–to manage relations and trade with the residents of Hokkaido. Through the port of Tosaminato on the northern Honshu coast, the Ando managed a flourishing trade of Japanese crafts and metalwork (especially tools) headed to the Ainu, while the Ainu sent down fish, furs, and other natural goods.

The relationship was mutually beneficial in many ways–indeed, Japanese tools enabled an explosion in the Ainu population, which in turn expanded onto neighboring Sakhalin Island and the Kurils as well as the Asian mainland. In fact, the Ainu became so powerful they actually defeated a continental tribe, the Nivkh, and seized some of their land–they were driven back only when the Nivkh turned to the Mongols for help.

Still, the Ainu-Japanese relationship was not a totally rosy one. A series of Emishi revolts in the north in the 1260s and early 1300s were supported by Ainu raids, and in 1454 the lord of the Ando clan got it into his head to try and expand militarily into Hokkaido to seize more land and power for himself.

The result was an absolutely brutal conflict with the Ainu known as Koshamain’s War, after the Ainu cheiftan who led the resistance. The Ando did win the war, but at substantial cost–they built 12 fortresses in the southernmost part of Hokkaido, the Oshima Peninsula, to hold their conquests, and in the fighting 10 of them were burned.

In the aftermath, the Ando would confine themselves to Oshima. They would also largely escape the fighting of the civil wars thanks to their remote position–but not the danger of internal strife. Late in the Sengoku period, the Ando were overthrown by one of their retainers, Kakizaki Yoshihiro–who in turn backed first Hideyoshi and then Ieyasu, and thus held on to his post. The Kakizaki–who changed their name to match their primary fortress, Matsumae Castle just west of the main Japanese settlement on Hokkaido, Hakodate–would manage the Ainu trade and govern the region on the shogun’s behalf for most of the Edo period.

They would be allowed exceptional leeway to do so, with the shogunate itself offering little oversight in terms of how the Ainu trade was managed. The Matsumae themselves oversaw a fascinating trade system that involved dividing up geographic trade rights with different Ainu communities between the clan’s vassals in the same that other clans divided their lands into fiefs. This system worked quite well for the Matsumae clan, their vassals, and the Japanese merchants who managed the trade on behalf of the samurai clans, because really–what samurai actually would know how to turn trade rights into something productive?

As for its impact on the Ainu themselves, well, honestly it was pretty variable. If your kotan, or settlement, was on good terms with the Matsumae, you could gain access to Japanese-made tools or equipment the Ainu could not produce themselves, giving your settlement quite an edge over its neighbors (and the chiefs who secured that relationship with the Matsumae a lot of power over their followers).

If your kotan didn’t have that relationship, meanwhile, it was at a substantial disadvantage. As a result, the Matsumae could pit villages against each other and keep them divided–in many ways, the system is reminiscent of that being used by European colonial powers in North America at the same time in history, where trade rights became a tool to pit indigenous communities against one another.

There would be Ainu rebellions against the Matsumae system–most notably the rebellion of Shakushain in 1669, who rallied some 30,000 Ainu to his cause. However, these revolts met with little success; Shakushain had numbers, but the Matsumae samurai had better training, weapons and armor, and reinforcements from the mainland. Shakushain himself was forced to surrender before too long, and within a year was killed by drunk Matsumae samurai out for revenge.

After that rebellion, the Matsumae would begin to clamp down even harder on the Ainu population, banning the sale of edged metal tools (potential weapons, in other words) or the learning of the Japanese language by Ainu (which would enable them to circumvent the Matsumae trade monopoly). Kotans which traded with Matsumae (which by this point was most of them) had to agree to terms requiring a clamping down on anti-Japanese dissent in their territory, and Matsumae dotted the Ainu lands with trading posts to “monitor” the region.

The full on colonization of Hokkaido and its incorporation into the territory of Japan proper would not begin in earnest until the 1870s–but particularly after Shakushain’s revolt was quashed, in many ways Hokkaido was already a Japanese dependency, if not a full on colony.

Now, I want to devote the last chunk of this episode to talking a bit more in depth about European powers and Japan, which means returning to the subject of the Dutch–the only nation that stuck around with the Japan trade after the seclusion edicts of the early Tokugawa years closed things down.

The Dutch trade, as we discussed in a previous episode, was managed by the VOC–a Dutch acronym that I will not try to pronounce in full because every time I try and read out something in Dutch I completely beef it.

Fortunately, VOC is just Dutch for the far more pronounceable East India Company–which I will refer to as the Dutch East India Company to distinguish it from the English East India Company.

Much like their English counterparts, the Dutch East India Company wasn’t just a corporation but a corporate government; it ruled a territory conquered in what’s now Indonesia and governed from Batavia (renamed Jakarta after Indonesia’s independence in 1949). During the Edo period, the VOC government in Batavia (and then later the Dutch government itself, which eventually assumed control of the VOC and its lands) would dispatch trade ships and a rotating permanent crew to man a factory–a trading outpost–in Nagasaki to manage the Japan trade.

That factory was moved around a few different times before being settled in Nagasaki–specifically an artificial island called Dejima constricted in Nagasaki’s harbor. Remember, Nagasaki was one of the cities directly controlled by the Tokugawa bakufu, so locating the Dutch outpost in that city was a way of ensuring the shogunate could control the Dutch trade.

Part of the reason for that was, of course, wealth–the Dutch trade had a pretty substantial value attached to it both as a vehicle for yet more smuggled Chinese goods and, as time went on, as a conduit for European-made goods into the country.

But far more important to the shogunate was information. The Dutch trade was the main method for the shogunate to remain aware of what was happening outside of Japan.

In particular, the head of the Dutch personnel stationed at Nagasaki–the opperhoofd, or “upper headman”–was required to come regularly to Edo to attend up on the shogun at regular intervals just like the daimyo were with the sankin kotai system we’ve talked about in previous episodes.

Partially, the goal here was political theater; it reflected well upon the prestige of the shogunate if even the emissaries of an overseas power like the Netherlands came to perform homage to him. But largely, the goal was to gather intelligence. The shogun and his advisors would often grill the Dutch on events outside of Japan–a way to keep up with goings on in the wider world in order to protect the security of Japan itself.

Of course, curiosity about the outside world wasn’t just restricted to matters of political importance. For example, in 1691 and again in 1692 the German physician Engelbert Kaempfer, who worked for the VOC, joined the Dutch mission to Edo and was received by the shogun (Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, shogun number 5, for those keeping track).

Here’s his description of the experience, as quoted in long form in Marius Jansen’s The Making of Modern Japan, and I love it so much that I’m just going to quote the whole thing:

“Soon after we came in, and had after the usual obeysances seated our selves on the place assign’d us, Bingosama [the Lord of Bingo] welcom’d us in the Emperor’s [shogun’s] name and then desir’d us to sit upright, to take off our cloaks, to tell him our names and age, to stand up, to walk, to turn about, to dance, to sing songs, to compliment one another, to be angry, to invite one another to dinner, to converse one with another, to discourse in a familiar way like father and son, to shew how two friends, or man and wife, compliment or take leave of one another, to play with children, to carry them about upon our arms, and to do many more things of like nature. Moreover we were ask’d many questions serious and comical; as for instance, what profession I was of, whether I ever cur’d any considerable distempers, to which I answer’d yes, I had, but not at Nagasaki, where we were kept no better than prisoners; what houses we had? whether our customs were different from theirs? how we buried our people, and when? to which was answr’d, that we bury’d them always in the day time . . . Whether we had prayers and images like the Portuguese, which was answered in the negative . . . Then again we were commanded to read, and to dance, separately and jointly, and I to tell them the names of some European Plaisters, upon which I mention’d some of the hardest I could remember. The Ambassador [Opperhoofd] was asked concerning his children, how many he had, what their names were, as also how far distant Holland was from Nagasaki . . . We were then further commanded to put on our hats, to walk about the room discoursing with one another, to take off our perukes . . . Then I was desired once more to come nearer the skreen, and to take off my peruke. Then they made us jump, dance, play gambols and walk together, and upon that they ask’d the Ambassador how old we guessed Bingo to be, he answer’d 50 and I 45, which made them laugh. Then they made us kiss one another, like man and wife, which the ladies particularly shew’d by their laughter to be well pleas’d with. They desir’d us further to shew them what sorts of compliments it was customary in Europe to make to inferiors, to ladies, to superiors, to princes, to kings. After this they begg’d another song of me, and were satisfy’d with two, which the company seem’d to like very well. After this farce was over, we were order’d to take off our cloaks, to come near the skreen one by one, and to take our leave in the very same manner we would take it of a Prince, or King in Europe . . . It was already four in the afternoon, when we left the hall of audience, after having been exercis’d after this manner for four hours and a half.”

Beyond staying on top of European dating and fashion trends (and of course political developments more broadly), the Dutch trade did have one other important function; it allowed for some technology from outside Japan to filter into the country. For example, in 1774 the doctor Sugita Genpaku completed a text he called Kaitai Shinsho (roughly, “A New Treatise on Anatomy”) that was a translation of a Dutch-language anatomy textbook. For doctors trained in traditional Chinese medicine, the text’s depiction of the study of anatomy based on dissection was a revelation–Sugita himself, who had learned to read Dutch as a student, had been inspired to do it after viewing an execution and then using the Dutch textbook to study the anatomy of the deceased.

Sugita’s story and Kaitai Shinsho are among the best-known examples of outside technology filtering into Japan, but the story isn’t unique; if you’re curious, check out episodes 469-470, which go over the history of how smallpox vaccination made its way into Japan before the country was “opened” to foreign trade.

So on balance, what we have here is a regime of foreign policy intended to control Japan’s external relationships–with China, Korea, the Ryukyus, the Ainu, and the Dutch–to manage them to the benefit of the existing political order.

And all of this did work to the advantage of the shogunate–at least, until the 1790s. For it was during this time, you see, that storm clouds in the form of Western empires began to gather on the horizon.

If you know your European history, you know that starting in the 1400s and 1500s Spain and Portugal began to construct substantial overseas empires. In the 1600s and 1700s, they were joined by powers like France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and eventually imperial Russia.

Russia in particular was the first threat to emerge to this carefully controlled foreign policy. As the empire of the czars expanded eastward and reached what’s now Siberia and the Russian Far East over the course of the 1700s, the czar’s explorers began to make their way into the Western Pacific, and by the 1790s they had reached Hokkaido.

In 1792 the first such expedition, headed by the Swedish Adam Laxmann in the employ of the czarist government, arrived in Hakodate–though Laxmann was successfully convinced to leave by promises that Russian ships would be allowed into Nagasaki (promises which were not kept), the experience was eye opening; the system for managing foreign relations was now being pressured from a new direction.

A few years later, the Napoleonic Wars would make their way to Asia as the Netherlands themselves fell under French sway during the conflict. As a result, Great Britain–now locked in a long-haul war against Napoleon’s France–began to attack Dutch shipping in Asia. In 1808, one Royal Navy warship, the HMS Phaeton, entered Nagasaki harbor to intercept a Dutch trade ship that was due to arrive. The Phaeton sailed into Nagasaki under a Dutch flag, and then revealed its true colors to wait for its target.

Nagasaki’s magistrate, Matsudaira Yasuhide, attempted to force the ship (captained by the youthful captain Fleetwood Pellew) to leave the harbor–Pellew refused, and demanded he be allowed to resupply his ship from Nagasaki to boot.

Pellew would eventually leave the harbor without incident–the Dutch ship he was hoping to intercept had in fact never left Batavia, because the war had wreaked havoc on shipping in general. However, the whole incident was a massive shock to the shogunate, particularly because it was revealed that many of the neighboring feudal lords had neglected the forces they were supposed to maintain to defend Nagasaki because they assumed said forces would never be used.

Magistrate Matsudaira would end up committing suicide for his failure to deal with the Phaeton–and officials of the shogunate were left to wonder.

The challanges to the shogunate’s authority over foreign relations were growing–how could they be dealt with?

We’ll find out the answer a few episodes down the line.