This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: crises about during the late Edo period. A crisis of samurai identity! Questions around vengeance, honor, and duty! And of course, the most confounding subject of them all: macroeconomics. But hey, I’m sure we can figure this all out as long as no pesky Americans show up to ruin things, right?

Sources

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan

Bitō, Masahide, “The Akō Incident of 1701-1703.” Translated by Henry D. Smith II. Monumenta Nipponica, 58:2 (Summer 2003), pp. 149-70.

Barshay, Andrew, Willem Boot, Albert Craig, Brett de Bary, Peter Duus, J. S. A. Elisonas, Grant Goodman, et al. “THE WAY OF THE WARRIOR II.” In Sources of Japanese Tradition: Volume 2, 1600 to 2000, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur E. Tiedemann

Walthall, Anne. “Peace Dividend: Agrarian Developments in Tokugawa Japan.” In Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850, Ed. Karl Friday.

Images

Transcript

Any time someone discusses the Edo period, they are contractually obligated to note that the golden age of the Tokugawa shoguns reached its apogee around the time of what’s called the Genroku Period.

Genroku is one of those nengo, or era names–as a reminder, since the 700s chroniclers in Japan had tracked the passage of time through named eras that would last for a few years until something–an omen, a bad event, whatever–necessitated a changing of the era. The Genroku Era began in 1688, and would last until early 1704.

And to be fair, I do think part of its positive reputation is simply the name–the two characters in genroku roughly translate as something like “origin of happiness”, which is definitely a positive spin on a period if ever I’ve heard one.

But to be fair to the Genroku Era, its positive reputation is not solely a matter of good branding. The period right around 1700 is generally agreed to be a real golden age of Japanese history, by which point the peace of the Tokugawa regime had led to a flourishing economy (and a thriving cultural scene built atop it).

We’ve discussed a few of the elements that emerged from that cultural scene before, from new theatrical forms like kabuki to the proliferation of fine dining. Others we have yet to talk about but are fairly well known outside Japan, such as the blossoming collector’s market for the woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e, or pictures of the floating world.

Of course, there’s a flip side to the obligatory Genroku Era discussion that must accompany any talk of Edo period history–seriously, I am fairly sure it’s somewhere in the constitution that you have to do it. Which is a follow up sentence something along the lines of: shortly thereafter, things began to go downhill.

To spoil history from a century and a half ago, I guess, the observant among you have likely noticed that Japan is no longer a feudal society–the Tokugawa shoguns are no more.

To be fair, the family is still around; they now run a charity dedicated to education about the Edo Period, which is cool, if a bit self-serving.

Anyway: most of the action of that collapse would take place over the 1850s and 1860s; we’ll start talking about it next week. But the seeds of the problem are quite a bit older, and they did start showing up within a couple years of the Golden Age of Genroku.

Some of these issues we’ve already covered, such as the social strain created by an extremely fixed status system–one which handed down power and status based on bloodline rather than talent.

Which could be very frustrating for those locked out of power, because as the centuries wore on, well–I think the best illustration of the whole situation is the fact that “daimyo no gei”, literally “skills of a daimyo”, a feudal lord, became an insult for someone who had no skills at all.

The humiliation of it all was keenly felt particularly by lower-ranking samurai as well as wealthy and educated commoners–who had enough of an education and proximity to power to feel keenly the humiliation of being locked out of it by a bunch of upper crust twits whose only claim to fame was being descended from people who were once important.

As we’ll see, the social classes most prominent in the movement to overthrow feudalism were these lower samurai and (to a lesser extent) educated and wealthy commoners–and given that sense of resentment, it’s not hard to see why.

More broadly, Tokugawa society always had this fundamental tension within its ruling class: who still called themselves warriors but who were, particularly by the golden age of Genroku, clearly not. They were professional bureaucrats whose job was to administrate and adjudicate, and no amount of wearing swords in public or reading about the glorious deeds of their ancestors or training in martial arts alongside philosophy was going to change that.

Which in turn raised a question that proved impossible to answer: what was even the point of the samurai anymore? After all, they’d been so successful in bringing peace they’d essentially worked themselves out of a job.

Many a samurai would grapple with this question, though I think it’s fair to say none found satisfactory answers. Some turned to Confucian thought, like the scholar Yamaga Soko, who emphasized that samurai should essentially serve the role of the scholarly gentleman of Confucianism: a moral sage whose virtuous character would inspire good behavior in those around them. As he put it in his treatise Shido: “The business of the samurai is to reflect on his own station in life, to give loyal service to his master if he has one, to strengthen his fidelity in associations with friends, and, with due consideration of his own position, to devote himself to duty above all…outwardly he stands in physical readiness for any call to service, and inwardly he strives to fulfill the Way of the lord and subject, friend and friend, parent and child, older and younger brother, and husband and wife. Within his heart he keeps to the ways of peace, but without, he keeps his weapons ready for use. The three classes of the common people make him their teacher and respect him. By following his teachings, they are able to understand what is fundamental and what is secondary.”

As an aside, that name Shido is hard to translate. It’s often glossed as “the way of the warrior”, and indeed it’s the same two characters that are used in the word Bushido–though that term is an anachronism that did not exist during the actual age of the samurai. But shi is also the character for the Confucian scholar-gentleman; so the book is both “the way of the warrior” and “the way of the scholar-gentleman”, appropriate for a text essentially arguing those two things are the same.

Others took a more…let’s call it traditional approach. These days, if someone has heard of any of the Edo period thinkers on this question of warrior identity, they’ve probably heard of Yamamoto Tsunetomo and his work Hagakure–Hidden by the Leaves.

The text is infamous for its rather extreme claims by Yamamoto, a samurai of Saga domain in Hizen province in Kyushu. Yamamoto, who was born in 1659, was infuriated by what he saw as the bureaucratization of samurai life and the loss of the core virtues of the warrior class–an ethos of loyalty and self-sacrifice.

In particular, he was furious when his lord Nabeshima Mitsushige died in 1700; Yamamoto wanted to follow an old custom called junshi, whereby he would commit suicide to follow his lord into the afterlife–a custom that, it’s worth noting, had not ever been particularly common or popular for reasons that I would hope are fairly obvious, and which at any rate had been outlawed both by the bakufu and by Saga domain itself.

Infuriated at this “weakness”, Yamamoto retired from public life, took the vows of a Zen monk, and would live the rest of his life in solitude. The only exception was a young samurai, Tashiro Tsuramoto, whom Yamamoto allowed to visit him on occasion after the young boy suffered some career setbacks and came to him for advice. Hagakure is Tashiro’s transcript, in essence, of the advice Yamamoto gave him.

The text is a fascinating mixture of idealized samurai traditionalism–and I do want to emphasize the “idealized” part, because Yamamoto was born over 50 years into the Tokugawa peace and had only fictionalized and idealized accounts of life before to go off of–with Zen Buddhist notions of anti-intellectualism. The result was a philosophy often summed up in the best known quotation from the text: “I have found that the Way of the samurai is death. This means that when you have to choose between life and death, you must quickly choose death.”

It’s worth noting, though, that Yamamoto didn’t just mean you should rush off to die just because. Instead, the idea of “quickly choosing death” meant that if called to die for your lord and domain, you should do so unhesitatingly–and that until that moment, you should devote yourself unhesitatingly to service. That unswerving devotion, in turn, will give you a strength beyond reason.

To quote another, less well known section of the text: “Bushidō is nothing but charging forward, without hesitation, unto death (shinigurui). A [samurai] in this state of mind is difficult to kill even if he is attacked by twenty or thirty people….ou must become like a person crazed (kichigai) and throw yourself into it as if there were no turning back (shinigurui). Moreover, in the Way of the martial arts, as soon as discriminating thoughts (funbetsu) arise, you will already have fallen behind. There is no need to think of loyalty and filial piety. In bushidō there is nothing but shinigurui. Loyalty and filial piety are already fully present on their own accord in the state of shinigurui.”

Again, a lot of these ideas are inflected with notions borrowed from Zen–the state of “discrimination” that Yamamoto attacks is described using terms borrowed from Zen to describe an irresolute mind to attached to this world to achieve enlightenment. Yamamoto also borrows heavily from Zen notions of time and our place in it: “There is really nothing other than the thought that is right before you at this very moment. Life is just a concatenation of one thought-moment after another.”

So his ideas are perhaps best understood not as a sort of desire to die immediately, but to live resolutely and in the moment–and, as a part of that resolution, not to fear death, since: “There is nothing that is impossible. If one thought is aroused, Heaven and earth will move in response. It is not that something is impossible but that people are too timid to make up their minds to do it.”

Even if Yamamoto’s ideas are less extreme than they are commonly thought to be they are still, for lack of a better word, pretty out there–and he was never particularly popular in his day, though he did have a following.

It was really after the downfall of feudalism, when the emergent Imperial Japanese Military began making use of Hagakure as a tool to argue that modern-day soldiers were like the samurai of old, and should embrace death in the name of the empire, that Hagakure really became famous. But that’s a ways off yet for us.

These two thinkers were not, of course, representative of the totality of thinking on this subject–they’re two examples of a very complicated conversation around what it meant to be a part of a warrior class at permanent peace. There are many, many others we could look at–but I think you get the general notion.

This fracture around the meaning of warrior identity was best exemplified, of course, in one of the most famous incidents of the whole period, known by a few different names: the Ako Incident, the Ako Vendetta, or the 47 Ronin Incident.

The incident has its origin, as the name might imply, in Ako domain, a moderately-sized feudal domain of 53,000 koku in what’s now Hiroshima prefecture along the coast of the inland sea.

In 1701, said domain was ruled by one Asano Naganori, whose family had ruled the area since 1645–the previous ruling family, the Ikeda, had been dispossessed after their daimyo, Ikeda Teruoki, had some sort of mental episode and went on a murdering spree.

And Asano Naganori was…at least not that. But he was also reputed to be, to put it frankly, an unpleasant person. Which perhaps explains how things went so wrong for him in 1701.

In that year, Asano made his way to Edo with an entourage for his sankin kotai–the regular attendance upon the shogun.

Asano was a fudai daimyo–part of the trusted group of Tokugawa loyalists–and was thus expected to work a job in the bakufu while he was in Edo. Specifically, he was tasked with working in the part of the bakufu bureaucracy responsible for receiving high-ranking envoys, mostly those sent by the emperor and imperial court in Kyoto.

Those envoys were of course intended to maintain the fiction of an equal working relationship between court and bakufu–in reality, one was entirely subordinate to the other, but that was beside the point.

Asano had done this job at least once before 1701, and had come into contact with one Kira Yoshinaka–who was one of the shogun’s hatamoto, or personal retainers, as well as a kouke, a master of ceremonies responsible for orchestrating all these elaborate receptions (among other things).

We don’t know exactly what happened between the two men–indeed, a big part of the issue is that this incident would later become so famous that the fictionalized reinterpretations of it would serve to obscure the actual history. For whatever reason, on the 14th day of the 3rd lunar month of the 14th year of Genroku (or April 21st, 1701 if you prefer) Kira and Asano got into a fight–and Asano, infuriated, drew his sword and slashed Kira.

Ever since the moment itself, much ink has been spilt speculating as to the rationale for the attack. The only surviving direct account of the attack comes from one Kajikawa Yosobei, who was clearly a part of the shogun’s trusted circle–he was one of the rusuiban, the officials charged with guarding the women’s quarters of Edo castle.

In other words, he had the sort of job where an untrustworthy person could cause a lot of embarrassment for the shogunate.

According to Kajikawa, both Asano and Kira were supposed to participate in a ceremony honoring ambassadors from the court–it was a yearly tradition that the shogun would dispatch envoys for the lunar new year to Kyoto, and that the emperor in turn would dispatch envoys of his own to thank the shogun.

The date of the Kira/Asano fight was also the date for a ceremony where the emperor’s envoys (who had arrived three days earlier) would be received by the shogun–gifts would be exchanged, and the emissaries would make their way back to Kyoto.

Asano was supposed to participate as the host escorting the envoy from Emperor Higashiyama, while another fudai daimyo (a descendant of Date Masamune) would serve as host for the envoys of the retired emperor Reigen (who had sent his own emissaries just to make things fun and complicated). Kira, as as master of ceremonies, was supposed to help MC.

According to Kajikawa (who was supposed to help present gifts to the emperor from the shogun’s consort). Things got off to a tricky start when Kajikawa got news that Kira had moved up the time scheduled for the ceremony. Unable to find Kira, he then tracked down Asano to check in with him and confirm the new plans. This done, he spotted Kira walking around the palace and went to check in–and saw a figure rush up behind Kira and attack him. This proved to be Asano, whom Kajikawa restrained to prevent Asano from killing Kira.

According to Kajikawa, Asano shouted kono aida no ikon oboeteru ka as he attacked–roughly, something like “do you remember my grudge from these past days?”

Asano was restrained and bundled off to be interrogated as to why he’d attacked; his response was to loudly repeat: “I have had a grudge against Kira for some time, and although I much regret the time and place, I had no choice but to strike at him.”

The attack took place around noon; by 4pm that afternoon, an order had come down from the shogun and his counselors that Asano was to be punished with an order to commit seppuku–ritual suicide through disembowlment.

That might seem harsh for a fight that had wounded, but not killed, Kira Yoshinaka–but the punishment was less for the brawl than for drawing a weapon within the shogun’s palace, which was a big no-no for what I imagine are obvious reasons.

The order was promptly carried out; Asano, in his final message for his samurai retainers in his Edo mansion and back in Ako, said: “I should have informed you about this matter in advance, but what happened today could not be helped, and it was impossible for me to let you know. You must wonder about the situation.”

He then composed one final death poem, and that was that.

And as an aside, I should note there’s one more account of the action, from a shogunal metsuke, or inspector, named Okado Denpachiro–but there are also some disputes as to the date said account was composed, and in particular that it was written after some subsequent events recast the brawl in a new light. And while this account is somewhat different–in particular, it’s way more critical of Kira as behaving snobbishly towards Asano–it’s similar and still emphasizes Asano’s grudge as the reason for the attack.

So, what was the grudge? We honestly don’t know. The most commonly reported account comes from a 1703 text called Ako Gijinroku, composed by a Confucian scholar named Muro Kyuusou.

To simplify his narrative somewhat, Muro says that Asano was supposed to offer Kira a “gift” in exchange for his tutelage on ceremonial matters–essentially, a bribe–but that whatever Asano gave was not enough. Kira was thus rather rude to Asano, and moreover insulted him publicly, which then incited Asano to vengeance.

It certainly makes sense, but Muro was not from Ako or directly connected to events and was likely just repeating hearsay he’d picked up from the Edo rumor mill.

Still, the reason for the attack matters less than what came next. In short order, a series of judgments came down from the bakufu. First, Kira Yoshinaka was not to be punished at all, despite having possibly provoked Asano. Critics of that choice would later point to the longstanding principle of kenka ryouseibai–a bakufu policy, though not written in law, of punishing both parties involved in a fight equally rather than apportioning punishment based on blame. That principle predated the Tokugawa peace, and was originally intended to keep the samurai of the various daimyo focused on killing their opponents rather than each other–a policy the shogunate had found it generally advantageous to maintain.

However, Kira did not attempt to fight back against Asano, and so the judgment of the shogun was that this was an assault, not a fight. To the extent that the incident made headlines outside the castle, meanwhile, it was mostly in the form of jokes about Asano’s martial prowess–a samurai should know that if you wanted to kill someone with a shortsword, you had to stab, not slash. Clearly, Asano wasn’t just a country bumpkin but neglectful of his warrior training.

The second judgment was that, given Asano’s flagrant behavior, his domain was to be stripped away from his heir (his younger brother) and instead handed off to Nagai Naohiro, a fudai daimyo who was popular with the shogun and was thus “upgraded” from his smaller fief of Karasuyama to the larger Ako domain.

Nagai, in turn, had his own followers he would take with him to his new posting–meaning that the samurai of Ako would have to scramble for a few remaining openings in Nagai’s following. Most, however, would be come ronin–samurai without masters. In other words, they would lose their stipends and their special social status, and be forced to fend for themselves.

Job prospects for a ronin were not particularly good. Given that there were no more wars, and that most domains had a hard enough time sustaining the warriors they already had, your chances of finding another lord to serve were close to nil. Of course, you could find work as hired muscle for a wide variety of businesses from the legitimate to the openly illegal–gambling, for example, was officially illegal but still widespread, and gambling houses always needed toughs to keep their clientele in line.

But this was a far cry from samurai status, and initially there were some concerns about the handoff–would former Asano retainers resist it in the name of their fallen master (or to make a point about their own disposession) and fight to hang on to Ako castle? The concern was real enough that the shogunate sent several officials to ensure things went according to plan.

But ultimately, they did. Nagai would take possession of Ako castle and its attached domain, Kira Yoshinaka would convalesce in his mansion in Edo, and it seemed the world had moved on.

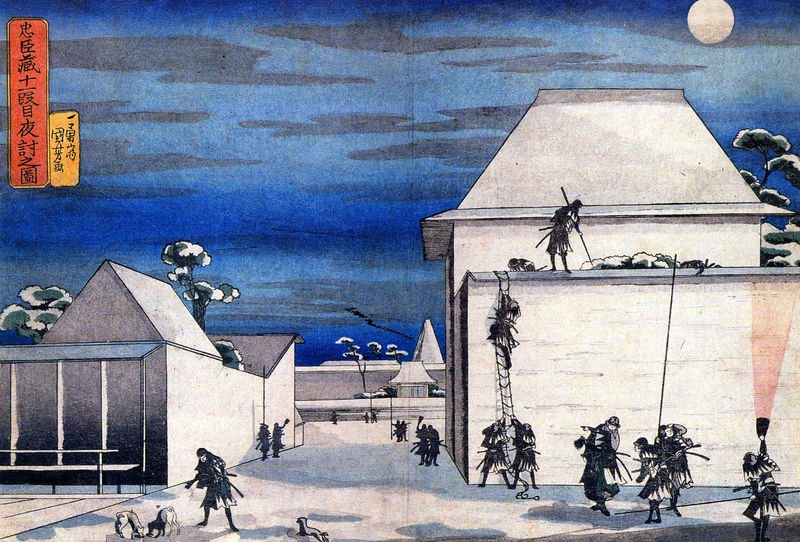

At least, it seemed that way until the 14th day of the 12th lunar month of 1702–or January 31, 1703, if you prefer. On that date, 47 former Ako samurai attacked Kira Yoshinaka’s mansion in Edo’s Honjo district (now a part of Sumida ward).

Led by one of the senior retainers of the Asano, Oishi Kuranosuke, the ronin were able to overwhelm the guards outside the mansion–who had initially been worried about an attempt at revenge against Kira but who had relaxed their guard as time went on. Kira was tracked down within the mansion, beheaded, and his severed head taken to the grave of Lord Asano at the Buddhist temple of Sengakuji. That grave, by the way, was 10 kilometers–a bit over six miles–away, so as you might imagine the parade of ronin with a severed head caused quite a stir in the city. Word spread quickly about what had happened.

After offering up the head, the Ako ronin surrendered to bakufu authorities and were placed under house arrest as the shogunate decided what to do with them. And those deliberations took a LOT of time. On the one hand, the ronin had in a certain sense defied the judgment of the bakufu–which had held Kira blameless for the original attack.

They had also broken the sixth article of the buke shohatto, the codes governing the samurai class–which forbade samurai from organizing and forming conspiracies (since instead they should just be taking orders from their lord). And I mean, if this wasn’t a conspiracy, what was?

On the other, they had also arguably lived up to the highest ideals of the class, and shown their loyalty beyond death to their master’s final wishes–revenge upon Kira. When interrogated, Oishi and the others claimed they were engaged in kataki-uchi–revenge killing, which was a legally protected action during the period for a samurai, albeit one that usually (and this is true) required you to get a permit for it.

Yes, there was paperwork you had to fill out to legally get your vengeance permit.

That said, it was fairly uncommon for a follower to take revenge on behalf of a superior; in most cases, a son or younger brother would be taking vengeance for an older male family member. Indeed, one of the first academic studies of revenge practices ever done, Hiraide Kojiro’s 1909 work Katakiuchi, found only one other instance from the whole Edo period besides the 47 Ako retainers.

That specific instance involved a woman named Takino, who worked in the Edo-based household of Matsudaira Yasutoyo, daimyo of Hamada fiefdom in what’s now Shimane prefecture. Takino would end up committing suicide after a series of insults by another of the household’s ladies in waiting named Sawano. Shortly thereafter, another of the ladies in waiting, a 14-year old named Yamaji, killed Sawano to take revenge for the death of Takino.

That vengeance tale would become the basis of a popular play (Kagiyama Kougyou no Nishikie), but was never as famous as the 47 ronin–and indeed, one woman taking revenge against another was a far cry from 47 samurai defying a bakufu edict in terms of concerns to state power.

Ultimately, the decision on the fate of the ronin would take until the 3rd lunar month of 1703. The bakufu announced that while the act of vengeance was righteous, it was still a defiance of the law–46 of the ronin were ordered to commit seppuku, which at least was a more honorable end than Kira’s guards, as those who had not died defending him were executed publicly like common criminals for running away from their master’s defense.

For reasons that are not quite clear, the 47th member of the conspiracy, Terasaka Kichiemon, was spared–he was both the youngest and lowest-ranking member of the group, but why he was not punished remains a mystery about which there has been substantial speculation ever since.

The case of the 47 Ronin ignited a massive debate around the role of the samurai within Edo society–had the ronin done the right thing by seeking vengeance or the wrong thing by breaking the law? Attempts by the shogunate to suppress this debate–which after all could go in directions critical of bakufu decisions–were not terribly successful, and in the end the 47 ronin became some of the most famous people of the Edo period. Their story is told and retold in books, movies, TV, and elsewhere to this very day.

More important than their stardom, however, is the fracture their tale reveals in warrior identity. That tension between samurai-as-warrior, always ready to publicly and violently defend his honor, and samurai as bureaucrat, whose main job was to enforce and follow the rules, was never really resolved and would remain fundamental to Edo period society.

And that sort of psychological tension would be important to the ultimate end of feudalism. For many of the samurai who ended up siding against the Tokugawa, the notion that they were acting in line with their ancestors, standing up and fighting rather than simply living as bureaucrats, was an attractive one.

Of course, there’s one more fundamental flaw in the system that became increasingly apparent after the golden age of Genroku: money, or really economic growth.

Peace, you see, had been enormously successful in bringing prosperity and stability, but the benefits of economic growth were far from evenly distributed.

Merchants and townsmen, those most directly participating in the thriving urban economy, did the best out of the new order. However paradoxically, the samurai class–ostensibly the rulers of the state–were not among the winners of the economic peace.

Well, at least some of them. Wealthy members of the warrior class–the daimyo and elite samurai of the domains, for example–well, they were living well. But for many other samurai things became increasingly economically bleak as time went on. For you see, things were becoming increasingly expensive, and the stipends the samurai class had to live on were not keeping pace.

It turns out that life as a Confucian bureaucrat concerned with moral philosophy nor experience as a warrior will make you a good economist, and so attempts by members of the warrior class to diagnose the cause of these shifts were not very successful.

For example, the anonymous author known as Buyo Inshi, whose criticism of Edo society we talked about two weeks ago, blamed these shifts on greed and laziness: “However, it appears that in the past two hundred years, people have grown weary and self-conceited from living in this splendid order, and perhaps because of too much ease and plenty, customs have changed greatly in recent times. Excessive luxury has caused both high and low to ignore the limits pertinent to their status. Opulence increases by the day and reaches ever greater heights by the month. People’s dispositions have become unstable, and the bedrock of trust and duty is worn thin.”

Obviously, the situation was a bit more complicated than this. The “excess luxury” Buyo Inshi was complaining about could be read as a simple peace dividend–the spreading of prosperity brought by the end of war, which in turn created opportunities for a genuinely national commercial economy that had not previously existed.

That prosperity wrought some truly incredible changes across the country. In the countryside Osaka, demand for fertilizer to farm cash crops was such that by the late 1700s it basically single-handedly sustained a herring-fishing industry up in Hokkaido, with the fish being ground up into fertilizer and then shipped down south.

In the Ina valley in the southern part of what’s now Nagano prefecture, many of the farming villages were so prosperous they were able to build their own kabuki theaters (some even had big city innovations like revolving stages). Obviously, not everywhere reached this level of prosperity, but the fact that parts of the country did is indicative of the power of Edo period economic growth.

At the same time, the structures of Tokugawa society did not allow for much of that growth to reach the warrior class. Initially, taxation in the Edo period was based on a system of harvest inspection–officials responsible for collecting taxes would go around to view the harvest and collect a percentage of it.

This process certainly worked, but it was both VERY time consuming and extremely open to corruption–after all, you could always slip your inspector a bribe to undercount your harvest.

This complexity–plus the fact that in an agrarian economy, income was always uncertain because bad harvests and even famine was a constant possibility, and the fact that over-farming actually caused some environmental degradation that saw arable land shrink by the 1720s–meant that many domains switched over to a fixed tax system. In this arrangement, villages were assessed a fixed amount in taxes that would remain consistent over time outside of the most extreme circumstances (like a famine). This was certainly simpler administratively, and it was actually a great deal if you were a farmer–agricultural returns would eventually bounce back, and when they did you got to keep more of what you farmed.

It was less of a good deal if you were a domain looking to get a good return on your taxes, for simple reasons of supply and demand.

Taxes, at this point, were still largely being paid in kind–a percentage of the harvest meant a literal percentage of what was harvested, which the domain would keep in a warehouse (usually in Osaka, home to much of the commercial economy) and then try to sell to convert it into cash.

But here’s the thing; as agricultural productivity rose, the supply of all these harvested goods (particularly rice, but also others) went up as well. And as we all know, when the supply goes up, generally speaking, the price went down.

As a result, the tax returns in harvested goods for each domain became increasingly less valuable as time went on. In theory, revenues from agricultural taxes were steady–in practice, though, they were going down in value.

At the same time, growing wealth across the country–particularly in the cities, but also in the countryside–was driving up the standard of living, increasing demand for the goods of daily life, from nice clothes to spices to anything else you can think of.

And as we all know, when demand goes up, so does price.

So everything is getting more expensive, and tax revenues are getting less profitable. And I think we can all see where that’s going.

To be fair, both the shogunate and the domains were aware of the issue, and tried measure to stave it off. But those measures were by turns draconian, ineffective, or both–for example, merchants in Osaka were enjoined to spend their wealth buying back rice, keeping it off market and thus driving up the price (and increasing the value of tax rice in the offing), but this both produced a LOT of protest from the merchants, who were being asked to essentially eat a loss on the government’s behalf, and in some cases exacerbated famines, because government revenues required keeping food off market.

Other attempts to drive up agricultural income, for example by opening new lands to cultivation, were mixed successes–by the late 1700s, pretty much all the land that was farmable with existing technology was being farmed.

And so the government was left to things like sumptuary laws, intended to outlaw non-samurai from purchasing certain luxury goods–which proved more or less impossible to actually enforce.

Pretty much every level of samurai society suffered from this funding shortage; the shogunate, for example, was constantly losing money on sankin kotai, because while every daimyo who came to see the shogun had to offer him a gift, the shogun had to offer gifts of his own that were higher value in order to demonstrate his superior station. In addition, maintaining the shogunate’s network of fortifications, and its arsenal to defend them, was not cheap–and those investments did not produce any economic returns.

Hardest hit were lower-ranking samurai, who were often told that because of their domain’s financial straits their stipends had to be cut–the domain simply couldn’t afford the cost. Some domains avoided this by taking out loans, but by definition that’s only a temporary fix–loans have to be repaid, and while samurai could simply refuse to do it (wasn’t like a merchant could take them to court), if they did future loans might be harder to find.

This was a serious problem by the 1800s, but not one that was necessarily unfixable. Agricultural reform, after all, was possible. But then, one more problem came down the pipe, in the form of a young, expansionistic country called the United States–and it would be the straw that broke the camel’s back.