This week: the bizarre story of an attempted coup in Korea that, along the way, touches on everything from Japanese liberalism to the birth of overseas empire.

Sources

Driscoll, Mark W. The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protectionism.

McMahil, Cheiron Sariko. “Japan’s First Feminists: The Life of Hideko Fukuda.” Off Our Backs 12, No 3 (March, 1982)

Patessio, Mara. Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan: The Development of the Feminist Movement.

Jansen, Marius B. “Oi Kentaro: Radicalism and Chauvinism.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 11, No 3 (May, 1952).

Images

Transcript

Today, I want to discuss an interesting little moment in the history of imperial Japan that, despite being often relegated to a simple footnote or offhanded mention, has a lot of value to say.

It’s a moment that ties in to everything from Japan’s tradition of political liberalism to overseas empire to relations with Korea to feminism–and which, in a nice bit of foreshadowing, sets up the next series of episodes I want to run.

So, today is all about the Osaka Incident of 1885, which I’d imagine most of you have never heard of–but which makes for one hell of a story in its own right. This is the moment when a group of Japanese reformers from the Freedom and Peoples Rights movement decided to gather weapons in Osaka, in preparation for a journey to Korea, where they would overthrow the local government and install a new regime based on liberal ideals.

Which is, uh, probably not what you’d expect people of that political stripe to be doing–so let’s talk about how they got there.

Which means that we need to do two things first: review Japan’s relationship with Korea in 1885, and remind ourselves of the Freedom and Peoples’ Rights movement.

So, for a quick refresh: during the latter years of Japanese feudalism, the relationship between Japan and Korea was one of stability and economic and cultural exchange. On the Japanese end, the relationship was managed by the Sou clan, a family of daimyo, or feudal lords, who had been recognized as the rulers of Tsushima–the island in the midst of the straights between Japan and Korea.

The Sou clan had worked its relationship with Korea’s monarchs out centuries earlier, back in the 1400s–the Sou clan would keep Tsushima, notoriously a pirate haven in earlier centuries, free of any unsavory characters who might be tempted to raid Korea’s coastline, and in exchange they would be given a monopoly on Japan’s trade with Korea.

The whole arrangement was very tidy for the Sou clan. The relationship was briefly interrupted in the 1500s, first by a series of riots by Japanese merchants in Korea around taxes and then (and more damagingly) by Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s attempt to invade the peninsula in the 1590s. However, in the early 1600s the So clan was able to broker a restoration of relations that would last for the next 250 years. In exchange for a nominal show of allegiance to the Korean kings, the Sou clan was rewarded with the right to send trade ships (an average of around 80 a year) and to import Korean products (particularly ginseng, silk, and texts). At the height of the trade, the Sou clan was making about 12,000 kilograms of silver in profit a year.

Meanwhile, the Kings of Korea would dispatch ambassadors to the shogunate to maintain friendly relations on regular intervals (particularly with the ascent of a new shogun). Those missions were a chance to maintain good relations and to show off Korea’s wealth and prestige–ambassadors were chosen from the most learned and accomplished of Korea’s notables, so as to make the best possible impression on the Japanese. And this appears to have worked; one ambassador recorded being mobbed in his inn in Edo by locals who had heard he was a master calligrapher and wanted to get a sample of his writing.

This stable and, if not friendly, at least cordial relationship lasted until the end of feudalism in Japan in 1868, at which point things changed dramatically. The new imperial government that won out in Japan was committed to Westernization and modernization, though what that meant exactly was a bit fuzzy in early days as competing factions within the government fought for control.

The Korean monarchy, however, was deeply traditional in its outlook. The kings of the Joseon dynasty, which had ruled Korea since 1392, were monarchs in the traditional Confucian style. The monarchy and government of Korea was based on that of imperial China, complete with an intensive series of examinations on the Confucian classics that were used to determine positions within the government.

Ostensibly, these exams were meritocratic–in practice, the sheer amount of education you needed to succeed at them (equivalent to a PhD in terms of the length of time you needed to study) meant that only members of the aristocracy, the Yangban class, had a realistic shot at passing.

This government system, invested in a very traditional understanding of Confucianism, worked well for over half a millennium in Korea–but by the mid-1800s it had begun to falter. First, Korea like Japan in the 1800s, was primarily an agricultural economy–and was hit pretty badly by a series of famines in the early and mid 1800s that badly hampered the nation’s economy and the government’s finances (in addition to, of course, killing a great many people). And then, as was the case in Japan, foreign incursions into Korean waters began to take place–Korea, like Japan, had a longstanding prohibition on the entry of Europeans and Americans.

The crisis that resulted ripped the Korean ruling class apart. The yangban aristocracy, chosen ostensibly for their merit in understanding the complex governing philosophies of Confucius, proved utterly without consensus as to how those philosophies applied in this situation. Some embraced a program of Japanese-style Westernization and reform: others an extremist Confucian conservatism and the rejection of all Western ideas. Some argued for a closer relationship between Korea and its longtime ally (and ostensible overlord) in China to counter the Western threat; others argued that China’s power on the world stage was faltering, and that Korea would be better served by a closer relationship with Japan (or Russia, another rising power in Asia at the time).

A skilled monarch could perhaps have navigated the divisions among his advisors and steered the country forward, but the ruler of Korea at the time was not such a man.

King Gojong, as he is known, ascended to the throne in 1864 at the tender age of 12, a decision made because of a longstanding precedent within the Korean system that a new monarch could not be from the same generation of the royal family as the previous one. Thus, when the previous king died, the throne passed to young Gojong (a distant relative, as the former king had no sons) rather than Gojong’s father (who was of the same generation as the former king).

Even when he grew older, Gojong proved a rather inept ruler; he was famously indecisive and constantly dithered between the two major personal influences in his life. First was his father, known to history as the Heungseon Daewongun, or Prince of the Great Court–and a hardline conservative Confucian who served as his son’s regent until the 1870s.

Second was Gojong’s wife, the ambitious and brilliant Queen Min, who was less conservative than her father-in-law and more open to some Western reforms.

We’re not going to recount the blow-by-blow of the result because we do have other things to talk about, but suffice it to say that this was not a mode of governance that was well adapted to crisis management.

And make no mistake, this was a crisis that needed to be managed. As far back as the early 1870s, the nascent imperial government of Japan joined the list of foreign powers pushing into Korean shores. Indeed, Japan was the first country to successfully force Korea to sign an unequal treaty in 1876–modeled on the same ones Japan itself had been forced to sign at gunpoint a decade and a half earlier by Western powers.

It would take until the late 1880s for a consistent consensus among Japanese leadership on Korean policy to develop–that policy being that Japan should seize and annex Korea–but even in the 1870s there was at least a sense among Japan’s leadership that the country had to distance itself from “backwards” Korea with its unmodern Confucian government to be accepted as the equal of the West, and that imperialistic treatment of Korea was an important step in that process.

All of this was happening alongside the second of our important factors this week: the Jiyu Minken Undo, or Freedom and People’s Rights Movement. We’re not going to rehash this entire political movement because it’s well beyond the scope of today’s episode, but as a reminder episodes 310-312 cover the history of this movement.

The quick refresh is that the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement represented a sort of liberal political movement–in the sense of supporting parliamentary systems, limits on government power, that sort of thing.

The movement had its heyday in the 1870s and early 1880s, when its members tried to take a stand against the autocratic government of the early imperial years. Through organizing political parties, petitions to the government, and sometimes organized protest these liberal political groups attempted to pressure the Japanese government into accepting more limits on its own authority–most of the members of the movement were admirers either of French style Republican government or British constitutional monarchy.

Unfortunately, their quest for political representation proved ill-fated. Some movement leaders, like the former Tosa domain samurai Itagaki Taisuke, were coopted by the government–Itagaki was promised a stipend to go to Europe and “study parliamentary government”, making it look like the political leadership was going to listen to his advice.

Instead, they just wanted the charismatic and popular Itagaki out of the country, figuring (correctly, it turned out) that the movement surrounding him would begin to falter without his leadership.

Other liberal-minded politicians who were members of the ruling elite like Okuma Shigenobu were purged from government–in Okuma’s case over a government scandal in 1882 the details of which I will not trouble you with here because in large part it was just a simple excuse to give Okuma the boot.

There were also, it is worth noting, substantial divisions within the movement itself, which contained many competing ideas around what exactly “freedom and people’s rights” even meant–in many ways it makes more sense to talk of several different movements reliant on similar slogans than one cohesive political force.

Some of these disparate movements also turned violent, leading to a government crackdown on liberal organizing more broadly that further dispersed the movement.

The upshot is that by the mid-1880s, the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement was beginning to flounder as its leadership was by turns isolated or removed from influence, and as its individual member groups were driven away from any real political power. The movement did lay the groundwork for the political parties that took shape in the 1890s–the first decade of parliamentary government in Japan–and which became the heart of the liberal movement in the Japanese empire.

So it’s not like the movement had no lasting impact–but it’s not like it radically changed the country either.

Thus, many leaders of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement were, by 1885, fairly frustrated politically–and looking for other outlets for their political energies now that the Freedom and People’s Rights movement was, clearly, not going anywhere fast.

Which takes us, at long last, to the Osaka Incident and its principle cast of characters.

The incident was, fundamentally, the brainchild of three people. First, we have Oi Kentaro, born to a farming family in Buzen Province (now Oita Prefecture) in Kyushu in 1843. His family were well-to-do, best shown by the fact that they were willing to pay for an education for their third son. In 1863, Oi was sent to Nagasaki to add some “Dutch learning”–that is, Western science, technology, and language–to his classical Chinese education, and apparently this really clicked with him. He developed a strong personal interest in chemistry, and eventually ended up with a position in the ranks of the shogunate during its final years helping to train its artillery crews.

After the fall of the shogunate, Oi spent a few more years in Japan’s nascent university system before turning to politics–like many of his contemporaries, an interest in Western science and technology led him eventually to Western political and social philosophy, and before long he was a member of the Jiyuto–the liberal party founded by Itagaki Taisuke, but which floundered without their founder’s leadership.

Our second participant is Arai Shogo, born 13 years after Oi Kentaro and on the other end of Japan–Shimotsuke Province, now Tochigi Prefecture. However, like Oi he was from a wealthy farming family that could pay for his education, both in classical Chinese language and philosophy and then, by the time he was a teenager in the early 1870s, in English. Arai Shogo was a farmer, but the closest thing to an aristocratic farmer there was–the eldest son of a village headman, and thus likely to become headman himself, and his parents clearly believed that an education would help him succeed at the task before him.

And doubtless it did help with all the administrative duties of the village head–but his education, like that of Oi Kentaro, led to Arai Shogo becoming interested in politics. By the late 1870s he was attending meetings associated with the Freedom and People’s Rights movement. In 1880, he joined the Liberal Party himself, and in 1881 he served a few months in jail for violating an ordinance banning unauthorized political meetings–an ordinance passed the previous year specifically to clamp down on organizing by the Liberal Party.

Our final and youngest member of this whole conspiracy is also, in my opinion, the most interesting: Fukuda Hideko. And the name is kind of a giveaway here; as those of you who know Japanese are familiar with, that -ko suffix indicates a woman’s name.

Fukuda Hideko, unlike her two male counterparts, was not a farmer but a samurai, daughter of a warrior of Okayama domain in what is now Okayama prefecture on the Japan Sea Coast.

I should note, by the way, that Fukuda is her marital name, taken from her future husband the liberal intellectual Fukuda Yusaku well after this point. Her original family name was Kageyama, so you sometimes hear her called Kageyama Hideko. You also sometimes (though less often) see her personal name rendered as “Eiko”, a different reading of the same characters. I’m going to use Fukuda Hideko, simply because that’s the way her name most often appears in English-language scholarship from what I’ve seen.

Anyway; Fukuda Hideko’s birth family prized education in the manner many samurai families did, and Hideko herself was extremely intellectually curious–picking up a good command of Chinese as well as several Western languages by the age of 15. She also developed an abiding interest in the figure of Joan of Arc after being leant a biography of her as a teenager.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for someone with that kind of intellectual background, she found herself drawn to politics before long, and in 1882 attended a rally of the Jiyuto in her home town of Okayama. There, she saw a speech by Kishida Toshiko, one of the few women actively involved in the Jiyuto and an early campaigner for women’s rights in Japan. Fukuda Hideko, who herself had just opened a girl’s school in Okayama with the help of her mother, was entranced by Kishida’s speech, which rallied against limitations on women’s legal and social rights and laid out a vision of women’s equality as a part of the struggle for liberalism in Japan.

Fukuda’s enthusiasm for the cause was not tempered when, in 1884, she drew the ire of the government because if it; in her capacity as a school employee she took several of her students to a Jiyuto rally, which in turn led the local branch of the Education Ministry to close the school for violating an official ordinance on political instruction by teachers.

Furious, Fukuda made her way to Tokyo, meeting Arai, Oi, and other disgruntled former Jiyuto members. And together, they hatched the plan that became the Osaka Incident.

So OK, what’s this plan that this episode is supposedly about but which I’ve been talking around a whole bunch at this point? Well it was, quite simply, to get a bunch of guns and money and a hard core of Jiyuto supporters, head over to Korea, and to try and overthrow the government.

Wait, OK, let me explain.

First, you have to remember that these people are committed liberals–and thus had just as little patience for the kind of conservative Confucianism that dominated in Korea’s government as they did the authoritarian centralism of Japan’s.

Oi Kentaro himself was a pan-Asianist who had become convinced of the importance of a Korean-Japanese union under the banner of liberal political ideas–this combination would, he believed, prove strong enough to resist the predations of other imperial powers and to champion liberal thought around Asia. He believed the Korean coup was necessary, “for the sake of Japan, but out of goodwill…in the fashion of global brotherhood.” One of his co-conspirators agreed, later testifying that the plan, “should not be seen as Japan interfering in Korea.” He would later go on to add, ““If you want to talk about our position toward Asia, I need to reiterate that we weren’t using Korea as ‘bait’ to be sacrificed, but were trying to bring about a revolution there as a way to improve the situations in Japan and China as well, in other words, throughout all of Asia. Moreover, this should be seen as one part of our larger strategy of Asia opposing Europe.” He would go on to say that, ““we are all opposed to the contemporary notion of the ‘strong devour the weak [弱肉強食],’ as these are the kind of ideas emanating from a truly barbarian world.”

Oi was not alone in this view: Arai Shogo would later say that the actions of the group were necessary to create a pan-Asian movement to oppose the West, especially the British. Indeed, Arai seems to have viewed the British as the greatest threat to Asia’s future, later saying that no Asian, ““should ever stop opposing the West … as the British Empire gets all its means for enjoyment from the blood and tears of Indians in Asia…“beginning with England’s colonization of Hong Kong and India and now stretching into Central Asia; the Orient has become the wrestling ring within which the Western powers show who has more brute force.”

Simply put, the plotters seem to have bought into the idea that their actions would liberate Koreans from an oppressive feudal system, and were thus fundamentally different from other forms of outside intervention in Korean politics (for example, the gunboat diplomacy employed by Japan and other Western powers). Oi and his colleagues saw themselves in a two-front conflict with despotic and imperialist government in Japan on the one hand and reactionary Confucian conservatism in places like Korea and China on the other. How much you accept that reasoning is, of course, up to you.

And it is true that the plotters did have potential allies in Korea that made the plan seem a bit less outlandish. There were the members of the Gaehwapa, or Independence Party–a group of Confucian officials within the Korean government who had embraced the idea of reforms on the Japanese model in Korea. Many of these officials, including their leader the scholar Kim Ok-Gyun, were also sympathetic in their written work to the ideas of liberalism, leading many Jiyuto members to see them as kindred souls.

The Independence Party was not in the best shape in 1885–in December of the previous year, its members had attempted a coup d’etat that had lasted for three days before being suppressed. Kim Ok-gyun had been forced, with the help of Japanese diplomats in Korea, to go into hiding in Japan, and the Independence Party members who were not killed in the coup scattered. Still, the coup had only failed because of Chinese military intervention against it–requested personally by Queen Min–so I can see how someone might think there might be some remaining sympathizers out there the plotters could work with.

But that is not at all the same thing as “actually a decent plan”; realistically, I don’t think this plot had a chance in hell of actually going off correctly in the sense of replacing the existing Korean government.

But then again, that didn’t necessarily have to be the goal either. Some of the plotters, based on statements after the fact, seem to have believed that even a failed coup might trigger a Japanese intervention and war in Korea–and that this in turn would lead either to protests against the government in Japan or a pro-Jiyuto uprising in Japan itself.

With all that said, if your main response to this is “that sounds completely insane”, frankly, I do not blame you in the slightest. I wouldn’t call this a good plan by any stretch of the imagination; it’s pretty pie in the sky, and involved some pretty wild leaps of logic to even come together into something that could vaguely be called coherent. Though none of the plotters would frame it this way in later years, I suspect a lot of what was driving the plot was a sense of frustration and rage at the Japanese government–a rage that could be vented against a weaker Korean government they also saw as a foe.

So ok, leaving aside our assessments of how likely any of this is to actually work, what was the plan itself? Simply put, Oi, Arai, Fukuda, and a few other Jiyuto members in on the plot decided to follow an age old principle of underground planning. To minimize the potential for disruption of the scheme, its supporters (of whom there were over 130 recruited individually by the ringleaders) would be dispersed into cells around Japan, specifically Kanagawa, Ibaraki, Toyama, Okayama, Tochigi, Nagano, and Fukuoka prefectures. Each of these cells would be small–between 5 and 20 members–and would have two tasks. The first was to make use of the Liberal Party’s various youth groups in the prefectures–called Yuikkan–to recruit willing young men to serve as potential fighters. Many of these youth groups, discouraged by government crackdowns on Liberal organizing, had become increasingly militant, and were thus natural places to recruit soldiers for both the coup and a potential uprising in Japan

Second, and probably more importantly, the local chapters were to fundraise as best they could in order to finance the uprising–after all, war is not cheap–and to send whatever money they could back to Oi Kentaro and Arai Shogo back in Tokyo (where they were engaged in the central organizing of the coup).

Finally, another plotter, Isoyama Seibei, was responsible for organizing the advance guard–some 25 men and women–who would go to Nagasaki and await instructions to head to Korea with the resources to begin laying the groundwork for the coup.

As the plan came together over the spring and summer of 1885, however, it began to run into problems. First, the decentralized nature of the plot’s leadership meant that before long, individual cells began to drift ideologically from each other. Most notably, two cells of the plot based in Kanagawa prefecture began to move away from the “Korea-first” plan and organize instead for a Japan-based uprising to be kicked off by the assassination of several leaders of the Meiji state.

The breakdown of organizational discipline within a coup d’etat is never a good sign, of course, and the issue only exacerbated the plot’s other and frankly far more important issue–money.

Overthrowing governments is not cheap, hence the need for constant fundraising. But the thing was, in 1885 Japan was in the midst of a pretty substantial economic downturn caused by government economic policies–the so-called Matsukata Deflation, intended to rescue the yen and the national account books from a period of massive and inefficient overspending in the 1870s. This worked, but at substantial economic cost, and on the one hand that meant great recruitment numbers for anti-government subversive types. But on the other, it meant scrounging cash to say, support your coup plan was a lot harder than it might otherwise have been.

And this, ultimately, proved the undoing of the whole plan. Some cells of the plot made ends meet by taking money from the ultranationalistic secret society known as the Gen’yosha, whose members supported greater Japanese influence on the Asian mainland (though for reasons of imperialistic expansion). But others turned to more classic ways to scrounge up cash in a tight spot, like bank robbery. Most notably, the Osaka-based cell robbed a bank in the city (which is why this is called the Osaka Incident) which in turn naturally drew the attention of the police. The investigation into the robbery led the investigators to Isoyama Seibei, the guy in Nagasaki who was supposed to be organizing the execution of the Korean coup. Isoyama, when he was captured, cracked and told the cops everything–and in a series of coordinated stings on November 23, 1885, the police dismantled the coup’s organization.

And I do mean dismantled; in total, 139 people were arrested in relation to the plot in a single day. After all, the cell system works well to prevent any one member from having enough info to do more than take out their individual cell if they’re caught–unless the person who is caught is one of the ringleaders and has info on every cell. And Isoyama was exactly that guy.

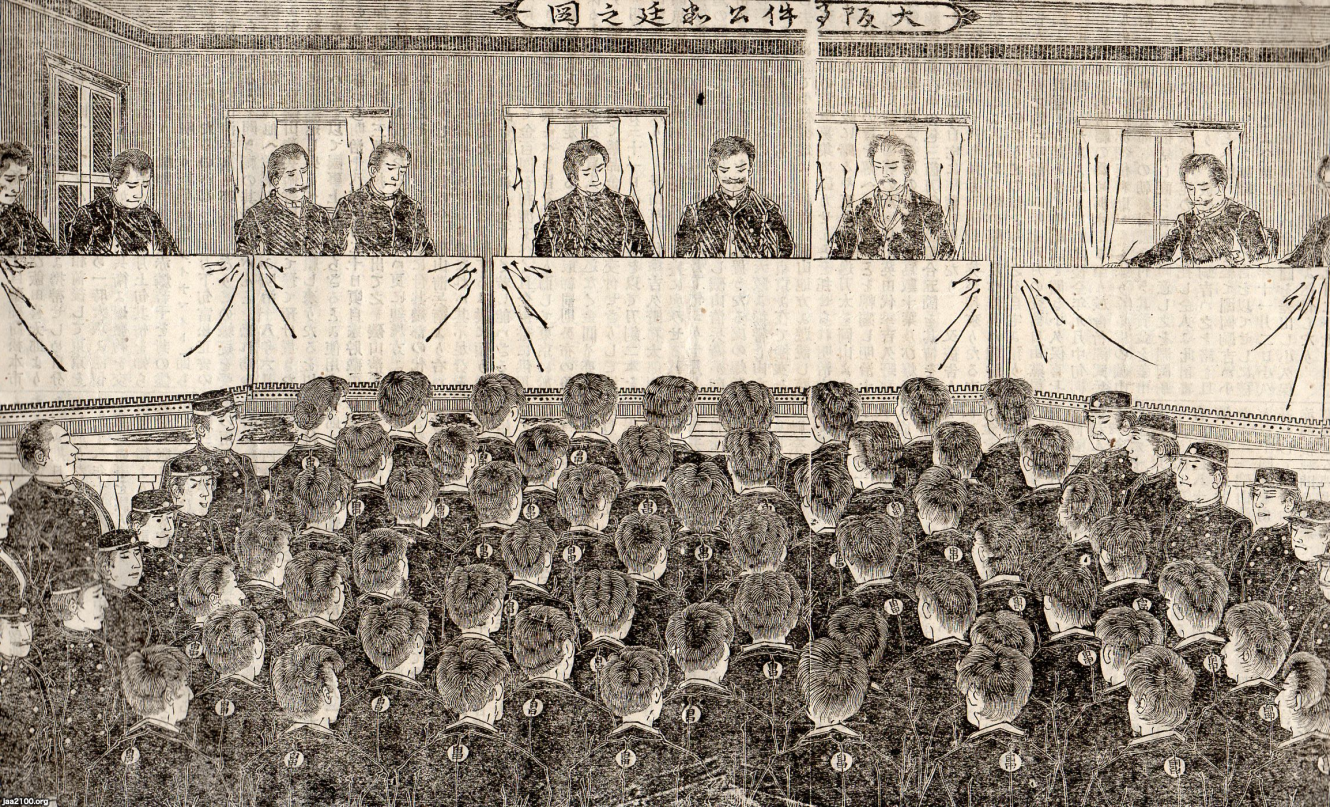

The arrests for a variety of charges, from conspiracy to illegal weapons possession, caused a media sensation–after all, the whole plan was, if nothing else, outlandishly daring. The resulting trials began in 1886 and lasted until 1887, which is where most of our knowledge of the coup and its motivations came from. The members of the plot, like Oi Kentaro, Arai Shogo, and Fukuda Hideko, spoke very openly about what they had been trying to accomplish either out of a sense of pride or because, with the plot foiled, a public trial was their best chance to get their views out there. The statements I’ve been quoting from Oi, in particular, all come from his trial transcript.

The trial was, of course, intently followed in the press, but it’s not like the conclusion was ever in serious doubt. The guilty verdicts rained down: Arai Shogo and Oi Kentaro both got nine years in prison for their actions; Isoyama Seibei, the leader of the coup expedition itself, got his sentence reduced to six because of his cooperation with the authorities.

Fukuda Hideko was given 18 months in prison, largely because in her case the prosecutors were only able to bring enough evidence to bear for a single charge involving the illegal possession of explosives.

Neither she nor anyone else would end up serving their full sentences; Fukuda got out after only 10 months owing to good behavior, while the ringleaders were released as part of a general amnesty proclaimed in February 1889 with the announcement of Japan’s first constitution. That constitution, of course, offered some tacit wins to the old Freedom and People’s Rights movement–it guaranteed some individual rights (within the limits provided by law, of course), and allowed for a parliament (with only one elected house, and which required you to be a man who paid 25 yen in taxes a year to vote). Others would, in the final decade of the 19th century and the start of the 20th, carry forward the cause of liberal democracy and personal freedom–but the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement was decisively defeated.

And of course, ten years after the Osaka Incident plot was foiled, Japan would go to war in Korea–but for reasons of imperial expansion rather than pan-Asian solidarity.

So that’s the Osaka Incident, but what of the central plotters? Interestingly, after their release from prison both Oi Kentaro and Arai Shogo would run for office in Japan’s first national election in 1890–and both would win seats.

Both were active in the early attempts to organize a “new Jiyuto” under the auspices of Japan’s limited parliamentary democracy. Arai would remain in office until his death in 1906; Oi Kentaro would end up moving out of politics and into business ventures releated to Japan’s position in Micronesia.

Interestingly, like a few other liberals of his generation, he would eventually move away from the Pan-Asianism of his youth. By the time of his death in 1922, Oi was far more of an expansionist than he had been as a young man, supportive of Japan’s empire as a vehicle to “liberate” Asia from the West, though of course that liberation in practice was the replacement of one master with another.

Fukuda Hideko, meanwhile, would take precisely the opposite tack. After her time in prison–during which she wrote an autobiography, warewa no hanshogai, or Half My Life–she would leave the Jiyuto behind. Instead, Fukuda would move politically towards socialism and feminism. She was actually one of the initial founders of Sekai Fujin, or Women of the World, a socialist feminist journal that began publishing in 1907. Later, she would publish an article in Seito, or Blue Stocking, one of the most famous publications in the history of Japanese feminism.

If you’re curious for more on that, see the series beginning with episode 329.

Fukuda would remain active in both the socialist and feminist movements–for example, she would join efforts to fight a government-backed relocation effort for Yanaka village, a small town on the outskirts of Tokyo that was to be demolished to be turned into a reservoir for the city’s water supply. Her advocacy saw her publication banned and several of her collaborators arrested.

Ultimately, Fukuda would remain active in politics until her own death in 1927. In her later years she would disavow the plans of the Osaka Incident, saying that in the end they were motivated more by Japanese nationalism and political chauvinism than she realized.

Which takes us nicely to the conclusion of our little tale, because I have to say I agree with her. I understand the ideals the plotters felt they were supporting, but ultimately to me the Osaka Incident is emblematic of one thing above all else.

Well, in a political sense at least. In a strategic sense it’s also emblematic of some deeply mediocre antigovernment planning. I realize it’s easy to armchair QB these things 130+ years after the fact, but like–this whole plan seems very ‘vibes based’ and grounded in a lot of unjustified assumptions about what the response to any of this would be.

Anyway: I think it’s very important to note that Oi Kentaro became a Japanese expansionist later in life. Indeed, that’s why I wanted to do this episode: we’re going to be starting a series on Japan’s colonial activities in Micronesia next week, and Oi–and other frustrated former Jiyuto members–are a big part of that story. They probably really did truly believe that expanding Japan’s empire was, in fact, helping the locals–bringing them “civilization” and protecting them from Western empires. But frankly, Fukuda was right–forcing empire on to others in the name of their own protection is not, really, something you do for their own good. It’s simply the same justification empire has always had–better us than them.

All the good intentions in the world, all the justified anger against the repressive nature of Japan’s government in the 1880s, doesn’t change the fact that this plot was something put together by Japanese people targeting Korea, an attempt launched “for their own good.” And ultimately, that kind of patronizing political attitude is, as we’ll see, self-serving–and does little to further the cause of those it’s supposed to help.

I am loving these episodes on obscure early Meiji politics. You are circling around the topic of my prospective PhD dissertation and I’m taking notes!