We’re exploring the history of crime fiction with Reynard, a rascal whose exploits are definitely not the sort of behavior you’d expect from a cute talking fox today. How did our vulpine antihero go from a murderous rapist to a cuddly kids’ character? Why did Walt Disney keep trying to make a movie about one of fiction’s nastiest criminals? And how long is Isaac willing to listen to descriptions of medieval butt jokes before he begs Demetria to wrap up this episode?

Content note: This episode is marked explicit for discussions of fictional sex, violence, animal deaths/murder, scatological humor, and very crude use of religious symbols. There is a detailed discussion of a trial revolving around a fictional situation that modern audience would probably consider a charge of sexual assault, but medieval audiences may have read as a false accusation.

Featured image: An illustration from a version of Roman de Renart published some time between 1290 and 1300. In this version of the Reynard stories, the animal characters ride horses, hold titles and castles, pay homage to their lion king, and interact with humans like farmers and monks but still retain their beastly natures and appetites. (Image source)

Another illustration from a very early copy of Roman de Renart created in the 1100s. This one shows a scene with Reynard and a hound. (Image source)

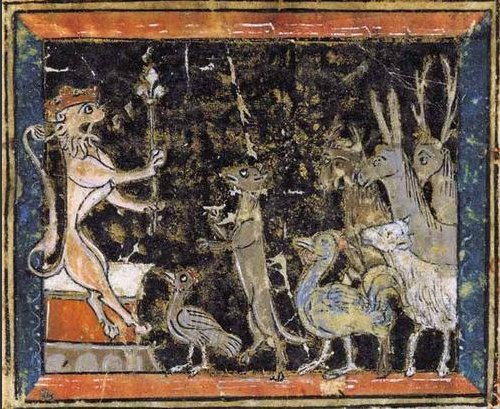

An illustration from a 1200s manuscript of animals at the court of King Noble the lion. (Image source)

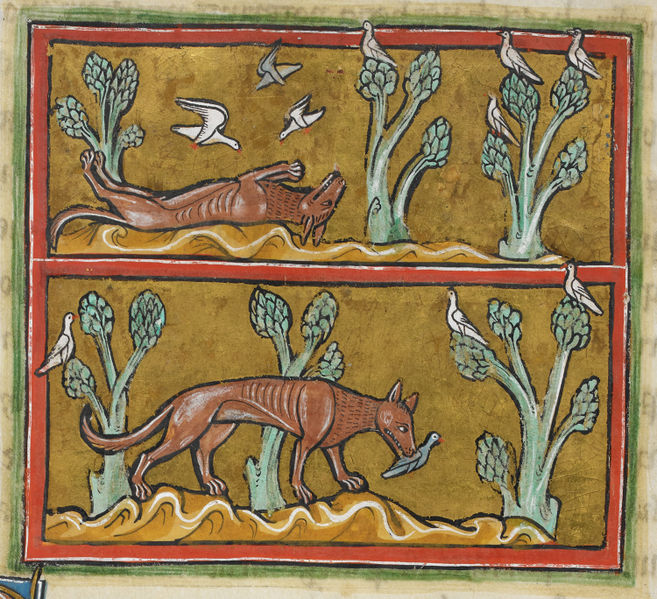

An illustration from a late 1200s bestiary of a fox playing dead in order to entice a tasty meal to approach him. Although this may not be a direct illustration of a Reynard story, Reynard does play dead very often and pulls a similar trick on a crow in some versions of his adventures. Whether this is real fox behavior or a bit of folklore is a matter of some debate. (Image source)

A carving from the 1300s or 1400s depicting a version of the Renard story. (Image source)

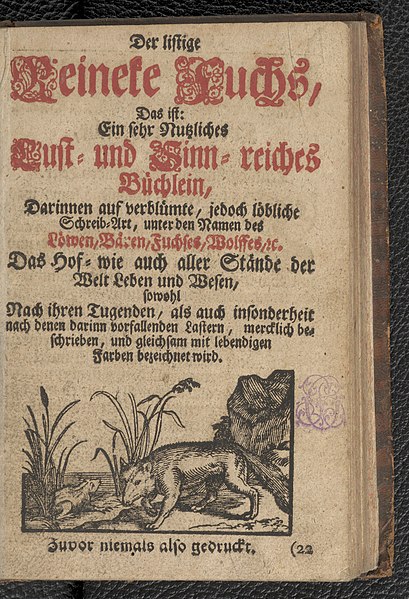

A German version of the story from the very early 1700s, with woodcut illustrations. (Image source)

A scene from Goethe’s version of the story. Like I said in the episode, I haven’t read it yet, but it does seem that despite Reynard’s more nuanced moral character there are still plenty of dirty jokes in this one. (Image source)

An illustration from the late 1800s of Reynard at the lion’s court. This comes from a Dutch version of the story and looks like it might have come from a kids’ book. (Image source)

The fox and the wolf, still mortal enemies, duke it out in front of the lion and his courtiers. An interesting note: by now, kids reading these illustrated books would be familiar with giraffes, elephants, and other animals that don’t appear in earlier Reynard stories but seem to have been included in these illustrations. (Image source)

A statue of Reynard erected in the Netherlands in the 1930s. (Image source)

A fox cub making off with a bird feeder from someone’s garden. Foxes can be very bold about stealing from humans and other, larger animals. (Image source)

Sources

Reynard story variants and scholarship about Reynard

- Reynard The Fox

- Ysengrimus

- The History of Reynard the Fox

- Robert Henryson’s The morall fabillis of Esope the Phrygian

- The Enigmatic Death of Cuwaert

- Reynke de Vos, Lübeck

- Chaucer’s Nonne Prestes Tale and the “Roman de Renard”

- Reynard the Fox : an early apologue of renown, clad in an English dress, fashioned according to the German model supplied by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- The History of Reynard the Fox: How Medieval Literature Reflects Culture

- Rape and Adultery: Reflected Facets of Feudal Justice in the Roman de Renart

- “Reynard the Fox” in the Seventeenth Century

- The Political Import of Goethe’s Reineke Fuchs

- Fox Mykyta

- New exhibition explores the long history of Anglo-Dutch relations from 1066 to 1688

- Hunting Reynard: How Reynard the Fox Tricked his Way into English and Dutch Children’s Literature

- Le Roman De Renard / The Tale of the Fox (1930)

- Disney’s “Reynard The Fox” – Part One

- Disney’s “Reynard” – Part Two

- In His Own Words: Ken Anderson on Disney’s “Robin Hood” (1973)

Genres and literary history

Other sources about history and Reynard authors

Fox behavior

- Video of a Tibetan Fox stealing prey from a Brown Bear

- Foxes in the Henhouse? Here’s How to Protect Your Chickens from Foxes

- Shoe-stealing foxes are a problem in suburbia, but there’s a reason behind the madness