This week, we’re beginning a month on radical activism in the 1960s with a look at the student uprisings of 1968. Today is all about where those uprisings came from, how they’re related to the “two Zens” of the 1960s, and the specific example of the University of Tokyo, where a debate about student medical internships turned into a violent and bloody battle between leftist student groups.

Sources

Andrews, William. Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture from 1945 to Fukushima.

Eiji, Oguma. “Japan’s 1968: A Collective Reaction to Rapid Economic Growth in an Age of Turmoil.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 13, No 12 (March, 2015)

Kapur, Nick. Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo.

Images

Transcript

I imagine that, if you have any familiarity with the history of the 1960s in the United States, you’re at least a bit familiar with the history of student activism at the time.

The political student movement was extremely active during this time, a major feature of the political landscape of the 1960s. From Students for a Democratic Society to the anti-Vietnam War movement, the student movement was a major driver of and participant in the debates around what was happening in America in the 1960s

And the interesting thing about the 60s is that this sense of chaos and opportunity the student movement was bound up in was not just an American phenomenon. The student movement was something global–and shaped the 60s around the world, not just in the USA.

We’ve already talked about how Japan’s 1960s radically reshaped the country–how the anti-security treaty protests in 1960 led to the birth of the conservative Liberal Democratic Party as we know it today, and how the very success of the protests also helped to undermine the leftist movement in Japan seemingly just as it was poised for its greatest success.

But one thing we have not spent that much time on is Japan’s student movement in the 1960s, which was briefly a major force in the social and political arena–before flaming out almost as quickly as it rose to prominence.

So today is going to be about the student movement in Japan, and especially one of the most pivotal years of that movement–1968–and how the rise and fall of that student movement reflected both tensions in Japan itself and a sort of broader youth rebellion that, in a certain sense, helped shape the uncertainties of the 1960s–and the world that came after.

But first, we should probably remind ourselves–what the hell is even going on in Japan in the 1960s? And to do that, we really do have to start by talking first about the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty.

As a reminder–that treaty has been in place since 1951; signing it was one of the preconditions for the United States ending its military occupation of Japan at the end of WWII. The original treaty, however, contained several terms deeply unfavorable to Japan–and so in the late 1950s, the newly ascendant Prime Minister and leader of the governing conservative Liberal Democratic Party took it upon himself to renegotiate.

That Prime Minister was Kishi Nobusuke, and he expected the renegotiations to go rather well. After all, the treaty was unpopular across the political spectrum in Japan–conservatives disliked that the current incarnation of the security treaty was deeply unequal (for example, allowing the US to make use of its bases in Japan without consulting the Japanese government), and leftists worried the treaty as written would drag Japan into the Cold War if it ever went hot. Everyone hated it, so who could object to renegotiation?

But Kishi deeply underestimated the depth of feeling about the treaty issue on the Japanese political left in particular. They didn’t just dislike specific aspects of the treaty–the left disliked having the treaty at all.

The result was a series of protests starting in late 1959 against the renegotiation of the treaty, picking up steam when Kishi began the process of having the new treaty ratified by the Diet–the national parliament–in the spring of 1960.

The protests grew out of control–particularly once Kishi responded to them by making use of the most heavy-handed tactics he could to force ratification of the treaty as quickly as possible rather than allowing for a full debate within the Diet.

People who were disgusted by Kishi’s heavy-handedness joined those with ideological opposition to the treaty to form the largest street protests in Japanese history–eventually leading to the storming of the Diet in mid-June and the death of one of the protestors. In the aftermath, Kishi–though he did get the treaty ratified–was forced to resign as PM.

Student groups were extremely active within the anti-treaty movement, led by the Zen nihon Gakusei Jichikai Sou Rengou–The All Japan Federation of Student Self-Government Associations, though it’s almost always referred to by the Japanese abbreviation Zengakuren in English.

The Zengakuren had initially been an outgrowth of the Japanese Communist Party, founded in 1948 by the JCP as a way to–in the early days of the postwar when old anti-communist laws were going by the wayside–get the party more influence on university campuses.

The Zengakuren was (and is) a centralized organization with a series of campus-based affiliates. You can think of it like the campus Democrats or Republicans on a college campus–a project run by students at the university, but affiliated with a larger political entity.

There was one key difference, however. In America, those college campus orgs are independently put together by students. In Japan, the Zengakuren could latch on to an existing organization–the jichikai, the student self-governing associations, essentially a combination student government and student union. Individual jichikai could–and often did–choose to affiliate with the Zengakuren, allowing the movement to grow rapidly because it could piggyback on existing campus student governments.

While it was initially very successful as a vehicle for JCP influence on campus, by the mid-1950s the party started to lose control of the Zengakuren. Partially, this was for international reasons–the acknowledgement by Nikita Khrushchev of the crimes of Josif Stalin during his “secret speech” turned many around the world against the USSR and Marxism in general, for example. But they were also unique to Japan; for example, in the early 1950s the Maoist wing of the JCP attempted to stage a revolution against the Japanese government. That revolution failed miserably, resulting in little more than a few bombed police stations–but it did a great job of turning the average citizen against the JCP, including students.

Thus, by the late 1950s, an anti-Stalinist, anti-Japanese Communist Party branch of the Zengakuren came to dominate the student movement. The group was called the Bund–Bunto in Japanese–derived from the name of Bund der Kommunisten, or Communists’ League, founded by Karl Marx back in 1847.

As the name might clue you on to, this faction was NOT anti-communist–just anti-JCP, and in particular anti-Stalinist.

The Bund was, in fact, an early example of what could be called Japan’s New Left. “New Left” is a term that was thrown about quite a bit in the 1960s, and one that didn’t ever really have a fixed meaning. Broadly, the new left was best understood in relation to what it was rejecting–the so-called “old left”, particularly the establishment socialist and communist parties as well as the trade unionist movement, all of which were treated in New Left literature as being compromised in some way–either because of failed revolution like the JCP, or because of ties to Stalinism, or more broadly because of their emphasis on issues of social class and party discipline over individual freedom and expression.

The JCP’s aborted revolution in particular stirred a lot of students over to the side of the Bund, and by the late 1950s this faction dominated the Zengakuren and established it as a force independent of the communist party.

It was the Bundist-led Zengakuren that took such a prominent role in the 1960 security treaty protests, for example. In the aftermath of the protests–arguably the biggest single success for Japanese leftism since the 1940s (the last time the socialist party had won an election–the Zengakuren seemed to be on the cutting edge of the Japanese “new left”–the groups independent of the leadership of “old left” organizations like the communist party.

But, like so many other left-wing organizations in the aftermath of the security treaty protests, the Bund-led Zengakuren’s victories proved hollow and short-lasting at best.

Because the victories of 1960 were, for many leftists, very hollow. It was true that the protests had turned the single largest mass movement in Japanese history–but much of that had been driven by Kishi’s autocratic behavior in forcing the ratification through with minimal debate, not necessarily pure opposition to the security treaty itself.

And the treaty had not been stopped–it was still ratified, Kishi made sure of that before he stepped down. The protests stopped Kishi from making a whole PR stunt of it–in particular, they shut down his attempt at a photo op during the ratification with the US president Dwight Eisenhower–but they didn’t stop the treaty itself, which was for the political left the whole point of the protests.

The unpopular Kishi had been brought down–a real win for left-wing parties who absolutely despised him (not unjustifiably: Kishi had been, after all, a backer of the old imperial government and a supporter of both the Second World War and Japan’s overseas empire, and had only narrowly escaped prosecution for war crimes). But in the aftermath, it wasn’t like the left got to take over; Kishi was simply replaced by another right-wing politician from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

And to make matters worse, his replacement–a former bureaucrat named Ikeda Hayato–proved extremely politically competent and was able to heal the rifts in the LDP created by the protests. The moment of conservative weakness passed fairly quickly–indeed, Ikeda’s program was not only able to heal fractures within the LDP, it also led to explosive economic growth in Japan–which in turn led many Japanese formerly aligned to the radical political left to abandon revolutionary politics. After all, revolution and radicalism are a lot more appealing when you’re poor and it feels like there’s nowhere to go but up.

This inability to capitalize on the momentum of 1960, and the not unjustified perception that the protest movement had failed in its actual goal–stopping the treaty–led to years of infighting among the broader Japanese political left. That included the Zengakuren–the failure of the Bund-led Zengakuren to stop the security treaty from being ratified led to the movement fragmenting into a series of competing “Zengakurens” spread over the country. From university to university, different chapters of the group would choose different Zengakurens to affiliate themselves with–there were breakaway movements that were explicitly revolutionary (often identifying themselves with one of the most extreme Communist leaders of the age, China’s Chairman Mao Zedong). There were more moderate factions, and ones that supported rebuilding the Zengakuren’s old relationship with the Japanese communist party. These various factions ranged from a few hundred members to a few thousand.

Sometimes, individual campuses would have multiple competing Zengakurens affiliated with different national Zengakuren movements. Waseda University in Tokyo was infamous for this, and was jokingly referred to as a “department store” for the different student movement factions.

The student movement looked to be on the ropes–its leadership was divided and student activism itself was increasingly unpopular. A 1965 survey of Japanese college students asking what they enjoyed most about college life found that only 1% put “student activism” first. And when, in 1964, several Zengakuren factions managed to agree on a joint action (protesting the arrival of a US nuclear submarine at the port of Yokosuka), they still only managed to scrounge up a few thousand protestors–not unimpressive, but not exactly the titanic showing of 1960 either.

The student movement looked to be on the ropes–but then, suddenly, it burst back to life.

Why remains something of a subject of debate, but a big part of it was probably the“turnover” of student generations, so to speak; by 1968, the students who had driven the 1960 protests were long out of university, to be replaced by a new generation who had not had the chance to participate in great moments of national political significance like the security treaty protests.

Now was their moment–for a few students, that was enough to get them interested in student activism. The numbers of such students, and the frequency of student protest, had been steadily growing starting around 1965 due to this generational shift. Beyond this, Zengakuren sects began to get increasingly savvy about recruitment, moving away from an overt focus on text and ideology and towards more of a social group structure–something we’ll talk more about next week.

In the shorter term, participation in the student movement was also driven by the growing popularity of New Left ideology as well as growing antipathy towards government policy, particularly around support for the American war in Vietnam.

The result was an explosive growth in the student movement–Zengakuren chapters at universities around the country saw massive upwellings of support from students who were outraged at what they’d seen. That upsurge in support was also driven by the So, by early 1968, the student movement had come back to life. What did it do with that renewed energy? In 1968, student activism primarily took the form of one of the iconic aspects of the 1960s student movement: campus occupations.

Campus protests were, of course, nothing new anywhere in the world–there’s a long tradition of university students being active in politics in that way. But especially in the late 1960s, a new tactic began to emerge–student groups occupying one or more campus buildings and barricading themselves inside in order to force campus administrations to listen to them on a particular issue.

This tactic was far from unique to Japan; in the United States, campus occupations took place at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in the fall of 1967, Columbia University in the spring of 1968, and at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University in the fall, eventually spreading around the country. In France, a massive student revolt in May of 1968 saw occupations of several university campuses in Paris.

This was, in other words, a global student movement–one that Japanese student activists drew inspiration from, even as students in other countries drew inspiration from what was happening in Japan.

In Japan specifically, the campus occupation movement was driven by an offshoot of the leftist movement–the Zenkyoutou movement, short for Zengaku Kyoutou Kaigi, or All-Campus Joint Struggle Committees.

These movements, like individual Zengakuren committees, grew up in specific campuses around Japan–there was a Tokyo University Zenkyoutou, and a Waseda University one, and a Keio University one, and so on. The earliest Zenkyoutou committees in fact sprang up at Keio and Waseda Universities, both private universities operating in Tokyo.

The “struggles” of these early Zenkyoto often involved fighting against tuition increases, as well as general concerns about the quality of their education–private universities at the time were infamous for relying on part-time instructors as a cost-cutting measures, and said instructors were as a result not often on campus to answer questions and often juggling classes in several places at once, resulting in what I’d call not exactly the highest caliber of classroom teaching from even the most willing and engaged.

As a former adjunct professor, that sounds weirdly familiar from somewhere.

Even full time faculty didn’t exactly provide the highest quality educations; most classes were mass lectures, and most students would never even speak to their professors–not exactly a scintillating intellectual environment.

Anyway: the early student movements responding to these sorts of pressures grew out of existing campus structures like the jichikai student governments or various politically-affiliated clubs. Interestingly, they often did not grow out of the Zengakuren, which was still as a whole an organization dominated by Marxists and the Marxist-adjacent.

Generally, the students who supported the Zenkyoto were not ideologically Marxist–many were intensely individualistic and obsessed with ideas of personal freedom and agency, which runs counter to the idea of Marxist “scientific” analysis that’s supposed to provide a precise pattern of historical evolution shaping human societies (rather than humans having the power to shape those patterns). The Zenkyoto, simply put, was very much a “New Left”, non-sectarian movement that billed itself in direct opposition to the old left of Marxism more generally, and especially to the factionalizing tendencies of those movements.

That said, existing campus Zengakuren groups were often at least supportive of the Zenkyoto, if not openly willing to work with them–though often the Zengakuren membership would be critical of the Zenkyoto’s emphasis on local conditions at a school rather than national politics. Still, there was enough cooperation and overlap between the two “Zens”, so to speak, for “zenkyoto” and “zengakuren” to have somewhat blended together in the parlance of the 1960s.

Both groups shared a self-identification as “New Left” groups appealing to a new generation of Japanese citizens, as opposed to the “Old Left” of traditional communist parties. That–and the fact that both were ultimately composed of students–gave them some sense of kinship, even with their different politics.

The two groups also learned from each other.The tactics adopted by the Zenkyoto were often based on Zengakuren ones, including things like sit ins, hunger strikes, and the occupation of campus buildings intended to force a response to their demands from the school administration. School administrators, however, were not willing to negotiate–one large Zenkyoto occupation at Waseda University in 1967 dragged on for 150 days of stalemate with administrators refusing to discuss anything with students.

In the interim, administrators even mobilized students–often either members of right-wing student groups or student athletes, who were viewed as more politically conservative–to attempt to break the occupation up. This resulted in student-on-student clashes on campus

It ended only when said administrators requested the intervention of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, who stormed the occupied buildings and beat the students into submission and arrest over 200 of them. When classes finally resumed, it was with police on campus to ensure no repeats of the prior issues.

This worked in the short term–but in the long term, it didn’t exactly address the root of the problems driving campus occupations. And those would flare up again in a big way in 1968.

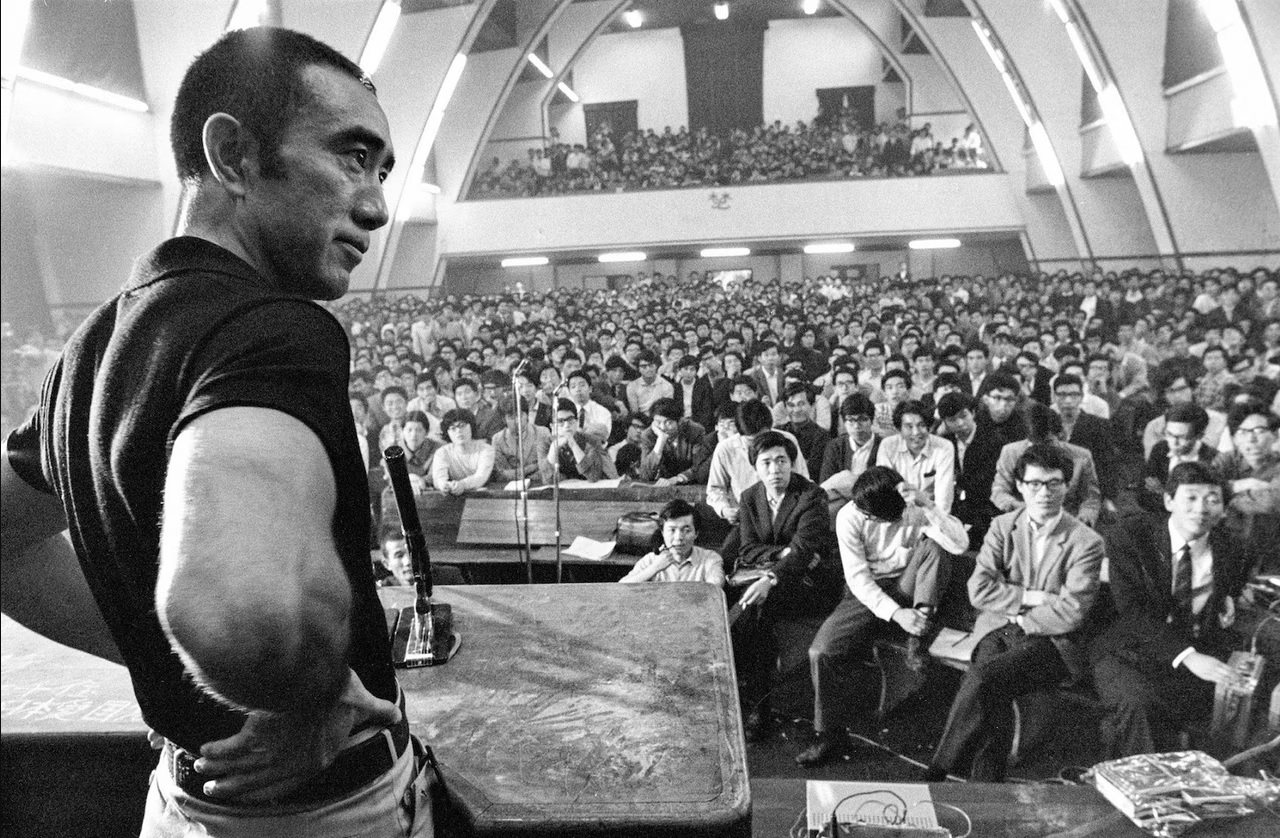

The biggest campus occupation of 1968 was undoubtedly Tokyo University, the most prestigious school in Japan more or less since its founding–still the highest ranked of all Japanese universities, and in the 1960s the recipient of 10% of the overall national budget devoted to the funding of public universities and colleges.

Tokyo University’s Zenkyoto movement was, like many others, a product of the overbearing and cost-cutting attitudes of the university leadership. The issue began with the university’s medical students, who were subject to a rigorous six year internship program that essentially forced them to engage in free labor for the university and affiliated hospitals. In January of 1968, the school agreed to reform the program, but the reforms did not go far enough for the medical students–who went on strike indefinitely as a result. The strike lasted, too–in mid-February, some of the involved students met with a tutor hired by the school to talk things over, and somehow the talk became a scuffle.

It’s still not entirely clear what happened or who threw the first punch, but things did get violent and the school clamped down hard as a result.

Seventeen medical students were punished–four, including one who was not even in Tokyo when it happened but was home in Kyushu visiting family, were labeled as instigators and expelled.

This did little to alleviate the ill feelings of the medical students, who then decided to disrupt the school’s graduation in March of 1968 (the Japanese academic year runs April to March rather than the September to June approach of the USA). University leadership delayed graduation to early April as a result, and called in riot police to ensure it would go forward this time–as a result, the medical students ended up occupying a university building, Yasuda Hall, with barricades to try and force the issue again.

Yasuda Hall is almost certainly what you’ve seen if you’ve ever seen a picture of Tokyo University–it’s this red-brick clock tower and lecture hall built in the 1920s with money from the Yasuda corporation, one of Japan’s major zaibatsu, and is in the heart of the campus.

Initially, student reaction to this decision was mixed–but it became decidedly more favorable to the med students when the university president, Okochi Kazuo, once again called in the cops to storm Yasuda Hall.

Fury at this heavy-handed approach led to a school-wide strike by students that would end up shutting down Tokyo University for the entire academic year–a strike that was backed by graduate students as well as a huge portion of the school faculty.

To enforce the strike, student organizations and the jichikai student government combined to form a Zenkyoutou, intended to combine and focus the efforts of the school’s students.

The university president, Okochi Kazuo, first attempted to wait things out over the summer holidays–when August came around, classes resumed, and the strike picked right back up.

By this point, Okochi was coming around to meeting the frankly very reasonable demands of the Zenkyoto–which were basically amnesty, so to speak, for the medical students and reform to the medical program–but then, things went to hell.

All university Zenkyotos had been loose movements ideologically–as we’ve already discussed, Zenkyoto groups tended to be defined by loose ideological commitments to intellectual agency and freedom as well as the shared campus space more than anything else.

And by the fall of 1968, the Tokyo University Zenkyoto began to come apart, primarily because radical factions of the Zengakuren started to get in on the action.

Specifically, the radical–but anti-Japanese communist party–factions of the Zengakuren ended up seizing on the strike as a means to bring attention to their Marxist politics. These factions, the names of which I will not trouble you with because you need a literal flowchart to keep track of their various splits and breakawys, already had a substantial presence on campus. Starting in the fall, those factions began to break away from the Zenkyoto line, and call in ‘reinforcements’ from other campus Zengakuren factions.

The result was the descent of the Tokyo University occupation into disorganized chaos and outright violence. Many of these Zengakuren factions were anti-Japanese Communist Party, but not anti-Marxist–several were radical Maoist factions enamored of China’s Cultural Revolution. Several of them went so far as to emulate cultural revolution style tactics on campus.

For example, one of the hallmarks of the cultural revolution was the so-called “struggle session”, where an accused counter-revolutionary was brought before the masses and subjected to a barrage of questions alongside insults and derision (and sometimes violence as well). Even if the struggle session was not a violent one they were still very degrading and psychologically damaging, particularly because they could go on for hours at a time.

Zengakuren factions emulated this tactic with professors or administrators perceived as opposed to their goals: one professor was detained for nine straight days, and one of the unviersity deans faced 160 hours (so about 6 and a half days) of nearly continuous interrogation. Obviously, these were not great conditions for the faculty; many left, and at least four ended up committing suicide due to the stress.

To be fair, these radical Zengakuren factions did not reserve their ire purely for faculty. The various Zengakuren factions also ended up fighting each other; by November, both the two largest factions on Tokyo University’s two major campuses (the Hongou and Komaba campuses) had occupied their own buildings and started fighting each other. So had another group–the Zengakuren factions were Marxist but opposed to the Japanese Communist Party, which put them naturally in conflict with the Democratic Youth League, or Minshu Seinen Domei (Minsei for short)–the youth movement of the Japan Communist Party. Minsei too entered the fray, occupying its own buildings and building up a “force” of students.

The result, starting in late October and early November, was clashes between the students of each of these different factions. Unlike the United States, it’s pretty hard to get weapons in Japan–guns are extremely heavily regulated to the point where they’re a very marginal presence, and even knives have some pretty strict laws governing them. Most of the students were armed, therefore, with long wooden sticks–often referred to as “gewaruto-bou”, or “gewalt sticks”, with gewalt being the German word for “violence.”

These paradoxically made the battles between the factions both less and more violent. Obviously, while you can still hurt someone pretty badly with a stick, it’s not quite like getting stabbed or shot. As a result, the police were more hesistant to directly intervene in these battles for fear of escalating violence that would probably not lead to fatalities–just to a lot of injuries. At the same time, this meant the battles were allowed to continue; the only group trying to stop them were the “non-sectarian” students still loyal to the Zenkyoto, who would try to break up the clashes or, failing that, serve as “medics” taking away the injured students for treatment.

When not actively fighting, the factions would hole up in their various fortified school buildings–and I do mean fortified, at this point. As the occupation of the campus dragged on, everything from barricaded doors to broken glass to honest to god barbed wire was deployed to help maintain each faction’s hold over their respective territory. Many of the occupying groups also got their hands on loudspeakers, used in combination with throne bricks and stones to try and harass opposing factions nearby.

One other interesting thing to note about this; while many of the students involved in the fighting were ideologues who genuinely believed in one faction or another, others were not. For example, there’s the fascinating case of Miyazaki Manabu–the son of a yakuza boss who followed the family business for a time before going to college. While there, he ended up falling in with one of the more radical Zengakuren factions (one of the pro-Japanese communist party ones), but not necessarily for purely ideological reasons.

In his autobiography (which I highly recommend reading, because Miyazaki is a fascinating guy and might make for a good episode of his own one day), Miyazaki talked less ideology and much more about image. In his own words, he was attracted to the, “awesome resolve of an organization prepared to use illegal means to accomplish its goal of overturning society. I felt that being a Communist was a lot cooler than being a Yakuza.”

That’s not to say that Miyazaki was totally without sympathy to the communist worldview and in it purely for the style, or that his views were representative of everyone involved–but we shouldn’t underestimate the extent to which part of the attraction of radical politics was simply the aesthetic of rebellion.

Regardless: The situation, to put it mildly, had gotten extremely out of hand. In November, the sitting president of the university, Okochi Kazuo, ended up having to resign for health reasons after being attacked by a mob during an attempt at negotiation that went sour. The resulting beating put him in the hospital for several months before his resignation.

In fairness, he probably would have ended up resigning anyway given how badly he’d bungled basically this whole damn thing.

His replacement was a far younger man, Kato Ichiro–who had a far better strategy for dealing with the occupation. Appointed as interrim president in November, he pursued a clever strategem of resuming negotiations with the Zenkyoto–while also negotiating separately with the other factions, particularly the JCP’s Minsei youth league.

As a result of this approach and general exhaustion with the violence of the strike, students and supportive faculty began to peel away from the movement. Zenkyoto, which was in the end a collection of several participating student groups, saw its participants dwindle; hardliners in the movement tried to bolster their numbers by calling in reinforcements from other Tokyo based universities, but by January, 1969, the balance was starting to tip. More and more students were abandoning the strike as the factions continued to fight and nothing appeared to be progressing–eventually, by mid-month, only Yasuda Hall (now covered in red banners and a giant portrait of Chairman Mao) and a few other buildings on the main Hongo campus were still under the control of the strikers.

Now in a far better position, Kato and the Tokyo city government finally called in the police to finish things off. On January 18, 8500 riot police descended on the campus–it took a day of hard fighting against students armed with everything from sticks to a makeshift flamethrower, but by the evening of the 19th the final holdouts on the upper levels of Yasuda hall were defeated. All along the way, the students holed up in the building were broadcasting via radio regarding the battle–their final broadcast ended with, “Our fight has been a triumph … It has by no means ended … We are temporarily halting these clock tower broadcasts until the day when we can truly commence broadcasting them once again from a liberated lecture hall.’

In told, 100 students and 500 policemen were injured–and Yasuda hall and many of the other occupied buildings were trashed and had to have their interiors more or less redone completely. Over 600 students were tried for their involvement in the strikes–the outcome often being publicity that torpedoed their ability to get jobs in the future as well as extremely long stays in jail, given the Japanese legal system’s permissiveness of long detention without trial.

The Tokyo University student uprising was one of the most visible examples of the student uprisings of 1968, but it was not the only one. We’ll cover some other examples, and the legacy of Japan’s 1968, next week.

I had seen in Japanese media a lot of mention of the turbulent 60s, one character even saying he “survived the 60s” and I had never understood what they were referring to. Now I see why. Graduating and getting a good job after all that WOULD be an achievement.