For part 2 of our Revised Introduction to Japanese History: what do we know about the origins of Japan’s imperial family? And how does that knowledge line up with the mythology built around the family’s rise?

Sources

Brown, Delmer M. “The Yamato Kingdom” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 1: Ancient Japan

The Basil Hall Chamberlain Kojiki translation. It’s not the most readable, but it is public domain!

Ooms, Herman. Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: The Tenmu Dynasty, 650-800.

The Japanese Historical Text Initiative at UC Berkeley holds a complete, searchable copy of Nihon Shoki (among other things).

Images

Transcript

Today, the imperial family of Japan is one of the most visible symbols of the nation. Indeed, that’s written into the modern day constitution of Japan itself, Article 1 of which states that, “The Emperor shall be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the People.”

In the preceding imperial era spanning the time from the downfall of feudalism to the end of WWII, the emperor played an even more prominent role politically as the legitimating symbol of the whole social and political order, in whose name Japan’s empire was being built (and won on the battlefield).

Even in the prior ages of samurai dominance, when the emperor was little more than a figurehead, the throne maintained something of an aura of antiquated mystery–indeed, this was partially why growing numbers of Japanese nationalists began to speculate that the imperial throne represented the most important part of Japan’s cultural inheritance, a divine link between this world and the realm of the gods themselves.

What I’m getting at here is that the imperial throne has a lot of history–and is very central to a lot of narratives of Japan’s past.

And that makes it all the more interesting–and kind of incredible–that we don’t really know where the imperial family is actually from or how they came about.

Well, I should say, skeptical academics don’t know. There are plenty of stories out there, some of which are taken pretty literally by some, purporting to explain just how the imperial clan got its start.

The most famous of these are, of course, the Kojiki, or Record of Ancient Things, and Nihon Shoki, or Chronicles of Japan. The former of these dates to 712 CE, the latter to 720–both of them represent the first attempts to create a centralized dynastic history of the imperial family and Japan itself, modeled after the practice of Chinese imperial dynasties.

However, there are a few reasons to view those documents with some skepticism, not the least of which is that they were compiled several centuries after the imperial clan emerged.

Oh also the gods show up a fair amount and are pretty actively involved in the narrative, which tends to make your average historian a bit skeptical of the veracity of the account for some reason.

Anyway–my plan today is to focus on the mythology of the imperial family and where they came from, and then dive into what the historical record can offer us on that subject for comparison. But first, here’s my brief attempt to summarize the narrative of the origin of the imperial clan–which is offered in both Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, though there are slight differences in the narratives of the two that we will touch on in a few spots.

Both Kojiki and Nihon Shoki begin their histories of Japan with the remote and misty age of the gods, and deal substantially with the creation myth of Japan and the historical genealogies of the gods themselves. For example, both deal with seven generations of gods who existed after the creation of the world, at first individual, and then in male-female pairs that were simultaneously brother and sister as well as husband and wife.

Which is probably something you could dig into in a very richly Freudian way, but such things are not uncommon in creation myths and this is not a psychology podcast, so let’s just move past it.

It’s the last of these seven generations, the gods Izanami (who is female) and Izanagi (who is male), who create both Japan itself and the other gods. The land is created first by engaging in metaphorical sexual activity–the dipping of a jeweled spear into the unformed mass of the earth, with the resulting dribble from the tip of the spear forming the first islands–and then with actual sexual activity that creates the remaining islands of Japan.

It is worth noting that the eight islands so created define “Japan” a bit differently than we do today. “Japan” consisted of eight islands–Shikoku, Kyushu, and the main island of Honshu, as well as the five outlying but sizable islands of Awaji (between Shikoku and Honshu), Tsushima and Iki (between Kyushu and Korea), the Oki islands in the southern part of the sea of Japan, and Sado island a bit further north off the Noto peninsula in Honshu.

Hokkaido and the Ryukyus do not appear in this mythology, nor were they thought of as a part of Japan at the time–their inclusion in Japan as we understand it is a substantially later phenomenon.

The two then proceed having children, a series of male, female, and genderless dieties that is WAAAAAY too complicated for us to get into here because oh my god there are a lot of them. They do this at first the old fashioned way–and if you don’t know what I mean, go ask your parents and/or health teacher and don’t tell them I sent you.

That ends, however, when Izanami gives birth to a fire god, Kagutsuchi, the unpleasant emergence of which kills Izanami–a reference, obviously, to the dangers of childbirth.

Izanagi, distraught, first burns his wife’s corpse while crying (his tears producing yet more gods) and then kills Kagutsuchi with his spear–the blood of his child producing even more gods, because now gods are just emerging every which way I guess.

Izanagi then famously decides to head down to Yomi, the underworld, to try and rescue his beloved–when they meet, she agrees to go back to the world of the living with him, but is afraid to show her face because, being dead, it is a bit less pleasant than it used to be.

And of course, if you know your mythology–and especially if you’re familiar with the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice–you know what’s coming next. Because of course Izanagi is tempted to sneak a peek at his wife, and does not love the corpsy visage he finds–and so flees in terror before they can leave the underworld together.

Izanami is, of course, not super impressed with this broken promise and sends the spirits of the underworld to pursue Izanagi–eventually, Izanagi escapes, sealing the entrance to the underworld behind him, while Izanami must remain in the underworld enacting her vengeance upon his creations (explaining the existence of death in the process).

Upon leaving the underworld, Izanagi purifies himself in a river–and it is from this act of purification that, once more, some gods are born. Most significant of these are the final three, born respectively from the water used to wash Izanagi’s left eye, right eye, and nose (presumably gross from all the crying he did for his lost love).

These gods are Amaterasu, the sun goddess, Tsukuyomi, the moon god, and Susano’o, the storm god.

Amaterasu, of course, is particularly important for our story– despite coming somewhat late in the game in terms of the overall divine genealogy. For his last children, Izanagi provides an important charge.

Tsukuyomi is to reign over the night, while Susanoo is to reign over the sea. Finally, Amaterasu is charged with reigning over the land of the gods, Takamagahara (literally, the high plain of Heaven).

The three divine siblings thus empowered, they begin their reign over their new lands. Unfortunately, it doesn’t take long for sibling relationships to get complicated–I suppose that’s just how these things work.

First, Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi have a bit of a disagreement–the Kojiki version has the two of them going down from the High Plain of Heaven to our world, to visit one of the gods who lives there. Said god serves them a banquet, but made entirely of things that god vomited up–which Tsukuyomi is so enraged by that he kills their host.

Amaterasu is not pleased by his violence, because while puke-based dinners are gross, murdering your hosts is just plain impolite. So the two split up–thus dividing the world into day and night.

The Susanoo/Amaterasu break, meanwhile, is a substantially more famous story.

This particular tale, as it’s related in these myths, starts with Izanagi getting annoyed at how much Susanoo pines for his dead mother–and deciding to handle it like any good parent would, by exiling his child from the plain of heaven.

Susanoo decides to visit his sister before he leaves, making his way up to her palace. But apparently his reputation precedes him somewhat, because she is not exactly thrilled to see him–and instead challenges him, suggesting that he is, in fact, up to something.

So she meets him clad in armor, prepared for a fight–Susanoo insists this is all aboveboard, and offers to undergo a trial to prove his sincerity.

In said trial, the sibling gods will either consume items they have on hand or swap items with each other to consume (depending on which version you’re reading), and then see what sort of gods they can create–with the results determining who is right.

Either way, Susanoo is victorious, but here the two accounts differ somewhat. In the Nihon Shoki version, Susanoo is gracious in victory–in the Kojiki, he goes a bit nuts at being proven right, and begins to rampage around Amaterasu’s lands–breaking down her rice fields and at one point killing and flaying one of her horses and throwing it through the roof of one of her halls, much to the surprise of Amaterasu’s various maids who are busily weaving various nice tapestries for her.

One of said maids is so shocked that she accidentally strikes herself in her own unmentionable bits with the weaving shuttle and dies from the injury, which really makes you wonder what that weaving shuttle was made of.

The Nihon Shoki version frames things somewhat differently, offering two variations of the tale (one where Amaterasu is injured by the weaving shuttle, another where one of her weaving maids succumbs to a hand injury), for reasons that are a bit unclear–but we’ll discuss one of the more common interpretations of this difference in a bit.

More important in the immediate term: in both versions of the story, this is where Amaterasu seals herself in a cave out of frustration with her brother (who in the mean time is booted out of the plain of high heaven to go cause trouble somewhere else). The remaining gods turn their attention to getting her to come out; led by Ame no Uzume, the goddess of mirth, they have a massive party (complete with Ame no Uzume stripping down and flashing everyone), much to the consternation of a very sad Amaterasu, who questions how they could be having so much fun without her.

To which the gods respond that a much greater goddess has come to them to replace Amaterasu–they trick her using her own mirror when she comes out to get a peak, seeing her own reflection and presuming it to be this new arrival and challenger. And of course, when she steps out to confront the challenge, the other gods pounce, pulling her out of the cave and sealing it behind her.

So, that’s good–crisis averted, things would be bad with no sun goddess around given that we all, you know, need the sun. But there’s some lingering bad blood between Susanoo and Amaterasu, and this is important for explaining what happens next–and how it leads, in the mythological narrative, to the foundation of the imperial line.

The story goes that Susanoo, having been exiled for his less-than-gentile behavior, is sent down to this world (called Ashihara no Nakatsukuni, or the Central Land of Reed Plains), where he goes on various and sundry adventures, including slaying the evil serpent Yamato-no-Orochi and claiming a mighty sword–what would become one of the three treasures of Japan’s imperial regalia–from the serpent’s guts.

In time, one of Susanoo’s sons, Okuninushi, is set up as the ruler of this realm–Susanoo himself having made his way to the underworld.

Eventually, either Amaterasu herself (in the Kojiki version) or one of the other gods, Takamimusubi (in the Nihon Shoki version) decide that our world, the Central Land of Reed Plains, is too greatly in disarray–and that the gods of heaven should pacify it.

This proves to be a bit of a challenge, however–Amaterasu dispatches several of her sons down to earth to deal with Okuninushi and the other various gods who live down there, but some (like her son Amenooshihomimi) simply refuse to do it on the grounds that the earth is too much in disarray, while others (like Amenowakahiko) jump sides and end up working with Okuninushi (for which Amenowakahiko is killed by an arrow from heaven after he kills a divine messenger sent down to check in on how things are going).

Still, the gods of heaven are not to be denied, and eventually led by the thunder god Takemikazuchi, they crush Okuninushi’s resistance (and in the Nihon Shoki version, Takemikazuchi literally crushes the arms of one of Okuninushi’s less bright sons, who challenges him to a wrestling match).

So, this realm is finally secured–but now, the ugly question of who is going to run things rears its ugly head. Eventually, Amaterasu’s grandson Ninigi-no-Mikoto is volunteered for the job, and is sent down to earth complete with three treasures to show heaven’s favor for him–a curved gem (yasakani no magatama), a mirror (yata no kagami), and Susanoo’s old sword (Kusanagi no Tsurugi, which Okuninushi had been made to surrender).

These three objects form the imperial regalia of Japan, symbol of the legitimacy of the imperial line–though nobody is allowed to actually see them, even the emperor himself. They are simply presented in boxes to him during the coronation ceremony, and then returned to storage. The actual regalia, of course, likely are not from heaven itself–and at any rate the original pieces were likely lost over the course of time. But nobody knows, because nobody is allowed to actually open the boxes that supposedly hold them.

Ninigi’s descent–which supposedly occurred in Takachiho in what’s now Miyazaki Prefecture–marks a transition in the mythology away from the realm of the heavens and towards this world.

Ninigi and his descendants would live in Kyushu for centuries; shortly after arriving, Ninigi would marry the volcano goddess Konohanasakuya and have three sons, whose progeny would spread throughout the land. In turn, Ninigi’s great-grandson would become Jimmu, the first emperor of Japan. Specifically, one of Ninigi’s sons (Ho’ori no mikoto) would marry Toyotama, a sea goddess/dragon–in turn, they would have exactly one child, a son whose name is a bit of a mouthful (Ugayafukiaezu).

Ugayafukiaezu would in turn marry his aunt and have exactly four children, the youngest of whom would become Japan’s first emperor.

I am, by the way, skipping over a lot here–both because trying to go over the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki versions would be extremely complicated, and because while it is interesting I don’t think a deep dive really serves our purposes here.

Jimmu’s story remains one that stretches credibility, to say the least–along with his brothers, he’s the one who leads the migration of Ninigi’s descendants from Kyushu to what became known as Yamato province–more or less where Nara is today in the center of Honshu, reigning for 75 years with a lifespan of 125.

Landing in Naniwa–what’s now Osaka–the imperial line engages in a series of bloody battles to conquer the land, the upshot of which is well summarized by Herman Ooms in his book Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: “The story is one of treason, murder, and bloodshed…the sun line of rulers prevails through perilous times, and the realm flourishes…”

This moment–and especially Jimmu’s enthronement as emperor, conventionally dated to 660 BCE–is the founding myth of the imperial household. Starting with Jimmu as the very first emperor and going all the way down to the current emperor Naruhito (ostensibly, emperor number 126), this represents (in theory) an unbroken imperial lineage that goes from Jimmu all the way back to Amaterasu herself–and which thus legitimates the imperial throne.

The reality, of course, is substantially more complex–and does not bear much resemblance to that story–though the story itself will have a lot of currency with Japanese nationalists of various stripes over the years, which is one of the reasons it’s worth knowing at least a bit about.

But still, it is naturally somewhat challenging to accept a literal reading of this origin story given all the divine intervention and magic powers and also literal dragons and such flying about–not to mention both the lack of archaeological evidence supporting an imperial line going all the way back into the late Jomon/early Yayoi period, and the fact that the two main sources for these events were compiled literally a millennium after they supposedly happened.

There are tantalizing hints here, perhaps, of the actual origins of the imperial family buried in these myths–for example, the narrative of the imperial family “descending” down to Japan and arriving in Kyushu, and then from there spreading to central Honshu before beginning the construction of their kingdom, seems highly plausible.

After all, as we know from last week there was a great deal of migration to Japan from the continent, especially Korea, during this period–naturally Kyushu would be the first place they’d arrive, and it makes sense that at least some of these migrants would go east in search of fertile pastures and eventually set up shop in what’s now the Kansai area of Honshu.

Of course, that would also mean the imperial family are descended from Korean migrants–a theory that is not uncommon among scholars today, and which the retired emperor Akihito did at one point express some sympathy for, but which remains very controversial in Japan. After all, right-wing Japanese nationalist types don’t love the suggestion that the fundamental symbol of the state came from Korea originally!

These myths are also suggestive in one other way. Early Japan was dominated by powerful clan families, of which the imperial family was at first but one–and during the early years of the Japanese state, merely the first among equals. These uji, or clan groups, wielded substantial power and authority in their own territories, leading to a deeply decentralized structure of power. They also had independent religious identities, with their own ujigami, or clan gods–Amaterasu, for example, being the ujigami of the imperial line.

Though it is clear that the imperial clan came to predominate over time through a combination of war and diplomacy, that power was still predicated on a very careful balance to keep the various uji divided from each other and tied to the imperial line.

And arguably, the myths of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki themselves illustrate this careful balance of power. The wide net of the family of the gods–Amaterasu and her siblings, or Ninigi and his many children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren, of whom Jimmu is but one–likely represent attempts to incorporate the ujigami or foundational mythical figures of these various clans into the imperial genealogy.

To use somewhat academic language, the goal here was likely to establish a sort of fictional kinship, tying powerful clans to the imperial line’s own mythology and establishing the notion that such and such a clan was related to the imperial line (and thus benefitted too from the power of said imperial line).

Certainly, by itself this would not be enough to keep such a tangled and delicate balance of power together–but in those delicate moments, every little thing helps, right?

This would also explain the multiple different variations of many of these stories, both between and sometimes within the texts of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. After all, if myths are being rewritten and added to support the narrative of the imperial line as needed, it only makes sense there’d be a few different versions floating about there, wouldn’t it

Still, there’s a limit to what we can learn (or infer) from mythology–and what we do know from more conventional academic sources about the origin of imperial rule in Japan diverges quite a bit from this more fanciful account.

For a start, there’s no real evidence of rule by the imperial line going back to 660 BCE, or anywhere close to it. The best guess of modern academics based on the available archaeological evidence is that the Yamato Kingdom–as the early state of the imperial family is often called–began to emerge some time in the 200s CE, almost 800 years after the date of Emperor Jimmu’s supposed coronation.

That evidence is archaeological–for example, the massive kofun burial mounds we talked about last week would be pretty good evidence for the emergence of a more powerful and organized state–and thus pretty fragmentary. That’s particularly true because Chinese records from the period are unreliable and fragmentary–from the collapse of the Han dynasty around 200CE until the rise of the Sui dynasty 400 years later, both China and Korea were divided into warring rival kingdoms, only some of which occasionally had any contact with far flung Japan.

As a result, the written record is basically unavailable until the 500s, and at that point–with the earliest domestic written records–things are still fragmentary.

It’s not helped by the fact that the Japanese government–which is naturally one of the largest sources of funding for research into Japanese history–generally did not fund projects dealing with this period up until the end of the imperial era, because the position of the pre-WWII government was that the legendary accounts of the divine origins of the imperial dynasty should be taken fairly literally.

It’s really been since 1950 that new and more intensive research has begun on this period. That research, for example, turned up evidence from Korea of the strengthening of the Yamato state. Korea at the time was divided into rival kingdoms, the strongest of which was Goguryeo in northern Korea.

In the 1880s, Chinese and Korean officials uncovered a stele erected in 414 CE to honor the 19th king of Goguryeo, Gwanggaeto–the stele honored the king’s accomplishments, including the defeat in 399 of “invaders from the land of Wa.”

Similarly, one of the sites associated with the early years of the imperial family, the Isonokami Shrine, contains a ritual sword with an inscription saying it is a gift from the king of Baekche, a rival Korean kingdom to Goguryeo.

This is highly suggestive, given that both the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki contain mention of one of the rulers of the nation, the 15th emperor Jingu, leading an invasion of Korea during her reign (which the Kojiki places in the 200s, but its dates are highly suspect).

And by the way–Jingu was a woman, one of several who have reigned during the course of Japanese history. Jingu’s historicity as a figure is somewhat disputed–other than her, six other women have sat in the imperial throne over the years, two of them doing so twice (abdicating and returning to the throne).

The Japanese term used for the emperor–tenno–is actually gender neutral; its literal translation, heavenly sovereign, is self-consciously different from terms like “the son of heaven” used for China’s emperor, which are of course distinctly gendered in meaning.

The relationship between gender and political power in early Japan is complicated–but it’s fairly clear that at least early on, there was more acceptance of female power than one sees on the continent (where, for example, China only ever had one empress regnant, the much maligned Wu Zetian, and my understanding is that Korea only ever had one as well during the monarchy (Queen Seondok of Silla, who at least has a pretty good reputation

At any rate–these two pieces of evidence point to a Yamato kingdom centralized and organized enough to dispatch armies over to the Korean peninsula by the late 300s, which tracks pretty well with the timeline we have from Kofun period archaeology in terms of growing sophistication of administration domestically.

Speaking of archaeology–while the modern restrictions of the Imperial Household Agency somewhat limit what scholars are allowed to do to what are (presumably) the burial sites of the ancestors of modern emperors, some limited work has been allowed since the postwar period.

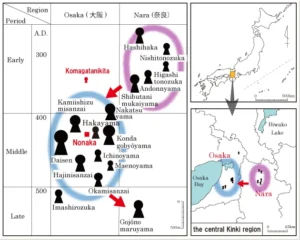

Those archaeological studies in turn have located the origins of the Yamato Kingdom in the area around what’s now Miwa Shrine to the south of the city of Nara proper (now a part of the city of Sakurai). In particular six kofun burial mounds located in that vicinity have been dated to the early to mid 200s, and finds in or around those mounds have suggested that they are probably associated with imperial ancestors.

They’re substantially larger than other mounds from that period, for starters, and even larger than burial mounds found in contemporary Korea (where kofun mounds were also used for the wealthy and powerful, though the ‘keyhole shape’ mound is unique to Japan). The limited excavations of the interiors of these burial mounds have also turned up evidence of substantial wealth and power in the form of elaborate coffins made from pine and bamboo, surrounded with large caches of mirrors, weapons, tools, and various metal ornaments.

It’s commonly suspected that what enabled the rise of this kingdom was the arrival of metal tools in the region during the Yayoi period, which steadily boosted agricultural productivity in what was probably an existing chiefdom–for a few of these sites have yielded pottery from earlier periods. In turn, the growing population required an increasingly sophisticated administration to manage it, and the ancestors of the imperial family–by hook or by crook–somehow seized control of that administration and made themselves into both a priestly and monarchical family.

As an aside, one of the reasons that the area around Miwa shrine was first investigated by archaeologists is that the shrine operates somewhat differently from others–there’s no shinden, or main worship hall where the central objects of veneration are stored. Instead, Mt. Miwa just behind the shrine is treated as the object of veneration–and it’s been theorized that this represents a preservation of an older form of worship from the early years of Yamato rule.

And by the way, both the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki do have legends of imperial ancestors who variously engage with (and even intermarry) the kami, or god/spirit, of Mt. Miwa–furthering the idea that there’s some sort of link there to the foundation of the dynasty.

By the mid-300s, Yamato power had begun to shift north, to what’s more or less Nara proper today–that shift being indicated, of course, by the construction of Kofun in the area. From here, from what we can tell, the Yamato kingdom began to dispatch invasion forces to the west and north, bringing even more of the Kansai area under their control–it’s sometimes theorized that the journeys of the epic hero prince Yamato Takeru are based on these campaigns, though the connection remains hard to prove.

Thus, by around 400 CE the Yamato Kingdom had extended its control out of its heartland in the Nara plains to the north and West across the main island of Honshu as well as parts of Shikoku–and had sent armies as far away as Korea to participate in that country’s civil wars.

Over the course of the 400s in turn, the power of the Yamato court would continue to expand as the kingdom came to encompass much of the West and South of the country, including the entirety of Shikoku and much of Kyushu. Once again, we see this reflected in the heartland of the dynasty, as the base of power shifts yet again–this time to the west, and the area along the Seto Inland Sea that would become modern Osaka. It was likely the need to use Osaka as a port–a launching off point for trade, messengers, and armies that held the growing kingdom together–that necessitated the move.

And we see this in the physical culture as well; the kofun tombs from this period are even larger, culminating in the massive mausoleum complex known as the Daisenryo, the largest kofun ever constructed and traditionally associated with the emperor Nintoku.

Speaking of Nintoku–it’s around this time that the historical chronicles that we rely on start to get more reliable–Nintoku, for example, appears in both the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki. Neither one should be treated as accurate accounts of his reign, of course; for one thing, they claim he lived to be 109, which seems rather unlikely at best.

Rather, it’s likely that starting somewhere at or before Nintoku (who is emperor number 16 according to the official chronology beginning with Jinmu), the mythology starts to reflect actual figures from the dynasty rather than mythic or semi-mythic ones.

Why do we suspect that Nintoku was a real person? Because around this time, the depiction of the lives of the emperors begins to shift–earlier, the emphasis is much more on the religious side of things, and in particular on the emperor’s relationship with the kami. However, beginning around Nintoku’s reign, the emphasis begins to tip the other way–the focus is far more on his involvement in military and political affairs, presenting a far more grounded (and thus, likely to be far more historically accurate) narrative.

Still, that’s speculation–but speculation based on incomplete evidence is pretty much what we have for the period.

Put together, the image that emerges is of a kingdom that, over the course of about 200 years, expands outwards from a strategically strong position in the center of the country, with much of that expansion taking place during the final 50 years or so before the middle of the 400s CE. This more or less lines up with the timeline of later written sources, though those sources generally try to push the date of the kingdom back further into antiquity–presumably as a way of legitimating the ruling dynasty by tying them back into the remote and misty past.

As archaeological discoveries continue, you’d have to expect that our knowledge of this period will continue to grow–but it’s always going to be somewhat unsatisfactory, simply because the lack of contemporary written accounts means that you’re so reliant on archaeological interpretation. And that in turn can be a very tricky thing to do, because–to paraphrase a common saying–there are a lot of unknown unknowns about this period that you simply can’t account for.

Next week, we’ll start moving into recorded Japanese history and out of the age of myth and legend–and discuss the start of the evolution of the Yamato kingdom into what could be called the first organized Japanese state.