We’re back at the beginning for Part 1 of a new miniseries: A Revised Introduction to Japanese History.

Sources

“The Earliest Societies in Japan” (J. Edward Kittier, Jr) and “The Yamato Kingdom” (Delmer M. Brown) in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 1: Ancient Japan

A good introduction to early Japanese history from Martin Colcutt, courtesy of the Japan Society

The scientific study I mentioned in the podcast: Caspermeyer, Joseph. “New Genetic Evidence Resolves Origins of Modern Japanese.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 32, No 7 (July, 2015)

Images

Transcript

When does Japanese history begin? It’s a seemingly simple question, without any real or easy answer. The written record seems like a natural place to start–and for many historians, that’s very much our comfort zone. But in Japan proper, said record only goes back about 1500 years–older references from Chinese histories go back an additional 500.But, given that the earliest traces of human habitation in Japan–likely by migrating tribes following herds of animals across the then still-extant land bridge from Asia– go back somewhere between 35,000-40,000 years ago during the pleistocene era, that still leaves a LOT of lost time.

There’s also, of course, the thorny issues of who appears in the written record (given that widespread literacy is a fairly recent arrival historically) and who even counts as Japanese in the first place–certainly many people holding Japanese citizenship today, from Ryukyuans to Ainu, come from populations that did not always consider themselves Japanese. But that’s a whole other discussion–and one we will be returning to down the line.

Without a written record to rely on, most of what we can learn about the vast majority of Japan’s history (at least in terms of chronology) comes from archaeology. And this, too, is not without its pitfalls–for example, in 2000, the Japanese archaeological world was rocked by a huge scandal. The newspaper Mainichi Shinbun published an article accusing Fujimura Shin’ichi, a prominent archaeologist responsible for some of the earliest chronological finds out there, of forging several of his own “discoveries” of some of the earliest artifacts in Japanese history–Fujimura had previously been something of a minor celebrity, because he sold his fake finds as being contemporary with or older than some of the earliest archaeological finds in Korea and Japan. His “findings”, which spanned decades before his forgeries were uncovered, thus appealed to patriotic sentiment in Japan–to the idea of Japanese exceptionality and particularity (which in turn perhaps explains why his forgeries were undetected for so long).

Fujimura’s forgeries are thus interesting because of what they reveal about how these early years fit into Japanese nationalism today–unfortunately, his work has also clouded somewhat our ability to make conclusive judgments about these earliest years of human habitation.

Anyway: from what we can tell, Japan was connected by land bridges to the Asian mainland up until about 20,000 years ago, and this was how the earliest settlers of the land made their way over. As already mentioned, they appear to have been following migrating animals, largely megafauna like Megaloceros giganticus, or giant deer (which were over 6 feet/2 meters tall, so pretty giant) or Naumann elephants (Palaeoloxodon namadicus). Hokkaido was even home to a population of mammoths, though my understanding is they never made their way south to the other home islands. All of these species in turn were wiped out by their human hunters, as happened in so many other places around the world.

These earliest human arrivals were part of paleolithic communities of hunter-gatherers with comparatively small populations. That word, paleolithic, is a fancy way of referring to the “old stone age”, the time in history distinguished by the use of the oldest known stone tools. Today, there are a few thousand known paleolithic sites scattered around Japan, particularly in the area of the Kanto plains–where the flat land and multiple riverbeds made for good hunting and foraging, even if there was the danger of the occasional big volcanic eruption.

About 12,000 years ago, the world of those paleolithic hunter-gatherers began to change rapidly, driven by two factors. First, they had–like their counterparts in other areas of the world–largely successfully hunted the local megafauna to extinction using their existing tools (and more importantly, their ability to collaborate on complex tactics via language). Second, the weather was beginning to change–after the last ice age, temperatures were rebounding as the world began to get warmer.

These shifts brought about what we call the mesolithic, or middle stone age–a period of transition away from traditional hunter-gatherer modes. And here’s where we have to stop and talk terminology for a second.

So as you might imagine if you’ve started to see the pattern here, the mesolithic, or middle stone age, will be followed by the neolithic, or new stone age. The neolithic period is the era of the adaptation of agriculture, of animal domestication, and just generally of the transition towards settlement that would come to dominate much of human civilization. In Japan, these two time periods–the mesolithic and neolithic–are in turn associated with two names that have come to stand for the earliest moments of Japanese history: Joumon and Yayoi.

Joumon in Japanese simply means “cord marked”, and is a reference to a term first coined by the American scientist Edward Morse, who came to Japan in 1877 and took an interest in some shell mounds he saw at Omori, now more or less right next to Haneda airport, during a train ride from Yokohama to Tokyo. Setting up an excavation of the site, he found several pieces of pottery he referred to as “cord marked”–cords of some kind had been used to make repetitive geometric patterns on the surface of the pot. The literal translation of that phrase, “joumon”, became the name for the period of Japanese history associated with that pottery.

From what we can tell, the first place in Japan where pottery was developed was in Northwestern Kyushu, where the process to make the pots was developed from trial and error and then spread east to the other parts of the country.

Pottery might not sound like that exciting of an innovation, but in fact it was crucial for this period of transition away from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. For one thing, pots were incredibly useful for foraging in coastal areas–for example, harvesting shellfish as a replacement food source. For another, pots could be used for this newfangled invention called cooking–boiling certain plants that were inedible raw made them actually consumable by humans, providing yet another replacement foodstuff. At this point, it’s pretty unlikely that said humans were actually planting these foodstuffs for harvesting–more than likely, they simply made use of local forage sites. But this was still a big step on the road to settled, agricultural society

Thus, pottery was kind of a big deal–and from what we can tell it was a totally homegrown invention. The earliest pottery from China actually comes after these earliest Joumon pots, which were often pointed on the bottom to allow them to be stuck into the ground. They weren’t the sturdiest–the pots were fired in low temperature open air pits, and have an unfortunate tendency to shatter into very small pieces if mishandled–but the technological shift they represented cannot be understated.

At the same time, the mesolithic was still a transition period–and the other big technological shift of the era was the development, also totally homegrown from what we can tell, of the bow and arrow to replace the throwing spear as the primary hunting tool. Bows appear to have been developed in northern Honshu, where the slightly cooler climate was not as well adapted to foraging as Kyushu and where hunting remained a larger part of the diet.

These two developments became the underpinnings of Joumon life, which sustained a peak population of about 250,000 people spread across the home islands by 5000 BCE. To put that in comparative terms, that’s about 7% of the total number of people who, on average, go through Shinjuku Station in downtown Tokyo every day (about 3.6 million people), so not a large population at all.

Joumon villages were generally small, about 6-10 dwellings. These dwellings were also fairly basic, usually built around a scooped pit dug into the ground to house an interior fireplace, with a grass or brush-wood roof held up by posts. From what we can tell, they were also largely disconnected, with at most a bit of local trade (for example, salt from the coast for stone from inland) to tie neighboring villages together.

Again, these communities were largely still sustained by foraging from what we can tell, though there’s some debate as to whether by the late years of Joumon villages had begun to engage in farming–deliberately cultivating crops they knew they could eat down the line.

Indeed, there’s some pretty intense ongoing academic discussion about how to break the Joumon into various subcategories based on sites from different periods–all of which is beyond our scope here because it involves some very deep dives into variations in local pottery as well as the remains of middens, essentially trash piles that were buried and preserved and thus give us some clues about how people lived day to day.

Now, some time around 900 BCE, you start to see the emergence of a new culture on the Japanese islands. We call this the Yayoi culture, named for the Yayoi neighborhood of Tokyo just north of what’s now the main campus of the University of Tokyo. Back in 1884, that area was home to two things–an Imperial Japanese Army firing range, and an old shell mound that was just beginning to be explored by archaeologists, but which was generally more famous for its large population of stray dogs. And it was in that old shell mound in 1884 that a young archaeological student named Tsuboi Shogoro, son of a samurai family that had turned to medicine and one of the first students of the new Tokyo Imperial University, found some pottery that clearly was not joumon in origin–rather than a rough, textured exterior, the pottery was smooth and painted with geometric designs. Clearly, this was a find from a whole new period of ancient Japanese history.

The precise dating of what’s now called the Yayoi period is something of a challenge–indeed, despite Tsuboi’s discovery, it took a further 40 years for the idea of a distinct Yayoi period separate from the Joumon to even come into vogue in academia.

If you look in older sources, they’ll generally say the Yayoi period starts around 300 BCE–today, 900 BCE is the more common dating, and there are (to my understanding) some academics who want to push things even further and lump some of the late Joumon period into the Yayoi one.

Partially, this is all a matter of some rather arcane discussion about changes in pottery techniques and other archaeological remnants, which (in the absence of the written record) serve as the main way we distinguish these various eras from one another.

Partially, however, there’s a bigger debate going on here about what the relationship between the Yayoi and Joumon cultures even was.

The Yayoi culture brought two big technological shifts to Japan in the form first of agriculture, and second in the form of metalworking.

Agriculture, of course, is probably one of the biggest technological innovations in human history, providing as it does a comparatively consistent and stable food source relative to foraging or hunting. In Japan, the earliest agricultural crops were wheat, barley, millet, soybeans, adzuki beans, peaches, persimmons, and–of course–rice.

Rice agriculture as we understand it now–based on leveled fields that can be flooded to irrigate rice plants–was distinctly a late Yayoi innovation, brought to Japan by Korean and Chinese farmers fleeing the mainland–both of those countries being divided, at this time, into competing warring kingdoms that made the region a somewhat unpleasant place to be if you were worried about being caught in the crossfire.

Metalworking, similarly, was brought over from the continent–Chinese bronzeworking dates back to about 3000 years ago, and ironworking was widespread by about 2500 years ago. Both of these technologies, of course, allow for far higher quality tools (and weapons too) than are possible with unrefined materials like stone, allowing for an even greater efficiency of farming and harvesting.

The fact that both of these technologies came over from the continent has led to the widespread theory that the Yayoi culture essentially represented a new wave of immigration into Japan–of continental refugees seeking to escape the wars of the mainland, and bringing new technologies with them.

Which makes sense, and certainly tracks with the available information, but raises the question of the relationship between this new Yayoi culture and the existing Joumon population. For a very long time, that relationship was theorized to be one of conflict, of superior Yayoi technology overwhelming and subsuming the Joumon population outside of a few aboriginal groups in the remote east and north of Honshu.

That reading owes a lot to theories that were in vogue in the early 20th century and which tended to read history through a “clash of civilizations” lens that treated conflict between different cultures as “natural” to a certain extent.

Today, that reading has fallen out of favor, driven both by some very necessary questioning of that clash of civilizations mindset and by some new advances in biology. For example, a genetic study in 2015 compared genetic data from Ainu populations (thought to be more closely related to the original Joumon population) to that of people from Beijing (thought to be more closely related to the Yayoi population). The findings of this study suggested hybridization between the two groups–that, rather than fighting, Joumon and Yayoi populations had intermarried and unified.

The study authors themselves are quick to note that their findings are not conclusive, and one way or another it’s unlikely we’ll ever know, but the whole saga does serve as a good reminder of the importance of not projecting our own prejudices back through time.

Yayoi metalworking of course opened up new frontiers in efficient agriculture through more advanced tools, leading to a steadily growing population that by its height reached around 2 million people across the archipelago–slightly less than the population of modern Nagoya, for comparison. Metalworking also led to the creation of ritual objects like mirrors and swords (possibly including the original imperial regalia of Japan, about which we will speak more next week), as well as the distinct bronze bells called dotaku.

If you’ve never seen a dotaku before, they’re these tall, thin bronze bells covered in decorative nature motifs. It’s somewhat unclear what they were actually used for, though the prevailing theory is that they were a part of fertility rituals intended to promote agriculture.

Speaking of agriculture, in many ways this is the central development of the period. More consistent food sources allows for a larger population, which in turn can be leveraged to grow more food–farming being something that “scales”, so to speak, very effectively off of the manpower you put into it. In addition to a growing population overall, Yayoi period farming led to larger villages–from 10 families or so to around 30, in larger, oval shaped houses (some of which could be up to 48 square meters, or 1500 square feet, in order to fit an entire extended family inside).

But this growing material prosperity did not just lead to larger populations–as farms grew, so did demand for flat farmable land, which in volcanic and mountainous Japan is a somewhat limited commodity, as well as for water to irrigate rice fields.

The result was the emergence of conflict between villages, and their organization into growing chiefdoms or even small kingdoms which could pool their manpower to fight neighbors for those resources. These early competing chiefdoms represent some of the first states in Japan–the first times where political power expanded beyond a single village, in other words.

These chiefdoms, in turn, were likely the genesis of both Japan’s oldest aristocratic families as well as Japan’s imperial line, which traces its ancestry back to this remote and misty prehistory (though as we’ll see next week, the story of where the imperial family emerged from differs from the archaeological record in some pretty important ways).

This is also, by the way, the moment where Japan first starts to appear in written records–though not its own. Instead, the first mentions of Japan appear in the dynastic chronicles of ancient China.

It’s not entirely clear when these Japanese communities began to formally contact their counterparts on the Asian mainland. The record here is a bit fragmentary, but it’s clear at least that by the end of China’s Han Dynasty in 200 CE, Chinese rulers were aware of the various chiefdoms and kingdoms of the Japanese islands.

First contact appears to have been made, naturally enough, in Korea; the northern Korean kingdom of Gojoseon was conquered by the Han Dynasty in 108 BCE, after which a good chunk of Northern Korea would remain under Chinese rule for about 400 years. In turn, ambassadors from Japan came to the Chinese ruled part of the peninsula some time thereafter–when is not precisely clear, and a bit hard to date. The Lunheng, roughly “Discourses on Balance, by the scholar Wang Chong, was written some time between 27-100 CE, and contains several offhand references to the “Land of Wa”–the name given to Japan in these earliest records.

By the way, you still hear that name “Wa” used for Japan today, but the character being used has changed. These days, the “wa” in “wajin”–the name often used for ethnic Japanese–uses the character for harmony. However, in the original Chinese, the “wa” means something like “dwarf”. Those sorts of pejorative names were commonly used in Chinese writings about non-Chinese peoples, a reflection of the belief that China’s imperial state was the beacon of civilization on earth and that other peoples existed on a distinctly lower rung of the civilizational ladder than China.

Fun fact: during World War II, some leaders in China, including Chiang Kai-shek, began to revive the older, more negative “wa” character in relation to the war with Japan.

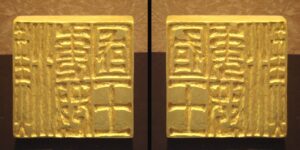

Anyway: both our timeline of Japan-China relations and our sense of what those relations look like are enriched by one of the greatest archaeological finds in Japanese history, found by a farmer in April, 1784 in what’s now Fukuoka in Northern Kyushu. The story goes that a farmer named Jinbei, while repairing an irrigation ditch, found a series of mounded up stones buried in the ground that seemed to be protecting something. Upon removing the top one (which was heavy enough that it took two people to lift)–he found inside a square seal composed 95% of gold, a bit less than an inch high. The seal was turned over to the local samurai rulers in the Kuroda clan, who passed it town until 1978, when the Kuroda family donated it to the city of Fukuoka.

The seal has five characters on it, which together read–King of Na in the Land of Wa of the Han Dynasty.” We can actually date the seal itself thanks to one of the dynastic histories of the period, the Chroncile of the Latter Han Dynasty, which describes an ambassador from the Land of Wa coming to the court of the Han emperors in 57 CE to swear his kingdom’s allegiance to China’s emperor, in exchange for which he received presents including a golden seal.

That same chronicle describes the kingdom of Na as being in southern Japan–combined with the fact that the seal was found near Fukuoka, that’s led most to surmise this is where the ancient kingdom was. However, no definitive location for the Kingdom of Na has ever been established.

So, it’s clear that by about 2000 years ago there are already a series of chiefdoms, or even rival kingdoms, around the Japanese archipelago, and that several of them were sophisticated enough to undertake the long sea voyages necessary to go to China. But why pledge allegiance to the emperor of China or accept a position as a vassal?

The answer, like as not, is one of the core motivating forces of all politics: trade and money. The formal tributary system of imperial China which you might be familiar with already was not in existence during the Han dynasty–it would be formalized over the subsequent centuries–but the same core logic applies here.

Good relations with China’s emperors opened up the potential for trade, and given the spectacular power and wealth of China’s emperors–far and away the strongest rulers in East Asia–an official relationship with them reflected well on a regional king who could use any extra legitimacy they could get.

Though Na itself appears only this once in the historical record, it’s pretty clear that contact with the mainland continued consistently if infrequently over the course of the next few centuries. By the end of China’s Han dynasty in the 200s CE, mentions of the “land of Wa” were cropping up fairly regularly in the written record, and those appearances were becoming a bit more detailed in how they described life in Japan.

Most famous among these is the Weizhi, or the chronicle of the state of Wei–one of the three kingdoms that succeeded China’s Han dynasty after its collapse.

The Weizhi is, naturally enough, most concerned with Wei’s own history–but it does reference goings on in other parts of the world as well. In particular, its appendices deal with the “barbarian peoples” on Wei’s border, including those of the land of Wa.

The Weizhi describes Japan as follows: “[The people of Wa] formerly comprised more than one hundred communities. During the Han dynasty, [Wa] envoys appeared at the court; today, thirty of their communities maintain intercourse with us through envoys and scribes…In their meetings and in their deportment, there is no distinction between father and son or between men and women. They are fond of liquor. In their worship, men of importance simply clap their hands instead of kneeling or bowing.

The people live long, some to one hundred and others to eighty or ninety years. Ordinarily, men of importance have four or five wives; the lesser ones, two or three. Women are not loose in morals or jealous. There is no theft, and litigation is infrequent.In case of violations of the law, the light offender loses his wife and children by confiscation; as for the grave offender, the members of his household and also his kinsmen are exterminated. There are class distinctions among the people, and some men are vassals of others…”

The Weizhi is also responsible for one of the most enduring mysteries of early Japan, thanks to its description of one of the island’s rulers: “The country formerly had a man as ruler. For some seventy or eighty years after that there were disturbances and warfare. Thereupon the people agreed upon a woman for their ruler. Her name was Himiko. She occupied herself with magic and sorcery, bewitching the people. Though mature in age, she remained unmarried. She had a younger brother who assisted her in ruling the country. After she became the ruler, there were few who saw her. She had one thousand women as attendants, but only one man. He served her food and drink and acted as a medium of communication. She resided in a palace surrounded by towers and stockades, with armed guards in a state of constant vigilance.”

Side note: the name of this queen is sometimes romanized as Pimiko, which is a variant reading of the characters used to write it. Himiko is the better known one, so I’m going to stick to that.

The Weizhi describes Himiko dispatching an ambassador named Nashonmi to Wei, along with one of her lieutenants (Tsushi Gori) and tribute in the form of “ four male slaves and six female slaves, together with two pieces of cloth with designs, each twenty feet in length.”

For doing this, Himiko was bestowed the title of “Queen of Wa, Friendly to Wei” along with her own golden seal with a purple ribbon (which, sadly, has never been found).

Himiko’s reign was not untroubled–her envoys complained to Wei of wars with neighboring rulers, which Wei dispatched an envoy to resolve. Subsequently, Himiko passed away, and, “When Himiko passed away, a great mound was raised, more than a hundred paces in diameter. Over a hundred male and female attendants followed her to the grave. Then a king was placed on the throne, but the people would not obey him. Assassination and murder followed; more than one thousand were thus slain. A relative of Himiko named Iyo, a girl of thirteen, was [then] made queen and order was restored…”

Now–this bit of text has naturally received a lot of attention from scholars, for a couple of different reasons. Obviously, it’s one of the first written accounts we have of life in Japan, and provides several juicy tidbits–for example, the ‘fondness for liquor’ that the natives of Wa have is used as evidence for the antiquity of sake brewing, and the discussion of etiquette and religion are fascinating as well.

But of course, the most interest has gone towards Himiko herself, for a few different reasons. First, of course, there’s the description of a female ruler and how she ruled–through witchcraft and sorcery, apparently.

Reading between the lines, it’s likely this is a reference to religious mysticism–it seems pretty clear that this is a reflection of the position of women in the earliest forms of native Japanese spirituality, today referred to as Shinto (though that term is anachronistic and came into use fairly recently historically). Likely, Himiko’s religious status is reflective of a more prominent role for women in earlier forms of religious practice–we’ll talk about this more when we talk about the history of the imperial family.

There are also plenty of other fascinating tidbits in there–the bit about her remaining unmarried suggests a link between ritual and sexual purity that does seem to continue in later forms of religious practice in Japan, along with the part about the 1000 female attendants and singular male.

And then, of course, there’s the line on the people “agreeing” on Himiko as their ruler. What does that mean?

These questions, and the historicity of Himiko as a figure, remain hotly contested, with various attempts having been made to locate her kingdom, referred to as Yamatai, throughout the years.

Particularly among later Japanese nationalist whose views put the imperial family in a very central role, it became rather fashionable to try and tie Himiko as described in Chinese records to specific powerful women from the history of Japan’s imperial family–thus verifying the antiquity of said imperial family well beyond what Japan’s own written records can provide.

All of these claims are highly tenuous, however–like as not Himiko was not an ancestor of the modern emperors, but one of the various local rulers with whom said emperors clashed over the course of their rise to power.

As political organization got more sophisticated, so too did the power of the rulers themselves. And it’s from one of the most visible signs of this power that the last era of history before the written record in Japan takes its name: the Koufun, or Tumulus period.

A tumulus is a fancy archaeological word for a burial mound–they’re also sometimes called a barrow. Essentially, this is a small hill one builds over the grave of a rich or powerful person–with the resulting earthen mound serving as an enduring testament to that person’s power and wealth.

These barrows were markers of the political power of rulers, in much the same way as the massive pyramids of Egypt built by the pharaohs.

There are thousands of these spread across Japan, from Kyushu up to central Honshu, with substantial variations between them. Some were round earthen mounds, others shaped somewhat like a scallop shell. The most distinctive design, found only in Japan, is the “keyhole” barrow–square in the front and rounded in the back.

Some of these kofun could be absolutely massive–the kofun associated with emperor Nintoku is in Osaka, and it covers 80 acres of land (.125 square miles, or .323 square kilometers)–making it the second largest tomb ever constructed, after only the massive and still largely unexcavated complex built to honor Qin Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of China.

The Kofun themselves are of course the most visibly spectacular remnant of this period, but there’s another reason they’re so important for us as we think about the arc of Japanese history–they symbolize the fundamental transformation, in many ways, of the era–which runs roughly from 250 CE to the mid 500s, the precise end date being a matter of some controversy for reasons we will discuss in future episodes.

The economic transformations of the Yayoi Era saw the emergence of local rulers like Himiko who held power over specific regions of the country. There were a great many such small kingdoms–the Weizhi, you’ll recall, references over 100 such that the Chinese were aware of by the 200s.

In a pattern we’ll see repeated a few times over the course of Japanese history, these small kingdoms naturally began to “separate”, so to speak, based on the qualities of their administration. Well-run kingdoms with strong leadership were naturally more prosperous–reflected both in an ability to conquer neighbors and in growing material wealth, most notably the massive kofun.

After all, you can’t afford such a massive tomb, or organize the workers necessary to build it, if your state is not well run.

These kingdoms scrapped for basically any advantage they could find, including taking in settlers from more advanced and wealthier parts of Asia like Korea and China who brought with them improved techniques for metalworking, pottery, and warfare.

For example, it was around this time that the horse was introduced to Japan, some time in the 300s CE and almost certainly from Korea. Many of these Kofun-era rulers maintained close cultural ties with Korea and some appear even to have participated in the peninsula’s various civil wars–it’s likely this was how the horse was introduced to the Japanese home islands.

Once again, naturally some kingdoms were more successful at conquest, administration, and simply attracting talent than others, and began to outcompete their neighbors as a result. And it’s starting around 400 CE that one of these small kingdoms really began to emerge on the historical stage.

It was based in what was traditionally called Yamato province in Japan, now more or less Nara prefecture. This is more or less smack in the middle of Honshu, nestled between the mountains of the Kii peninsula and the coastal area that’s now Osaka. The exact history of the clan that ruled this area is somewhat controversial because of a lack of contemporary documentation of their rise–but it’s likely that rise was enabled by a combination of warfare and shrewd dealmaking with potential rivals to turn them into allies and vassals.

As a result, by the 400s, what would become Japan’s imperial family was emerging as, if not the rulers of the country, at least the head of a coalition of powerful families that were on their way to consolidating the beginnings of a Japanese state.

We’ll look more at the emergence of this family, and the mythology surrounding them, next time.

I’ve so been waiting for you to more detailed episodes chronologically like this, History of Rome style. I hope this turns into another super long series, like how Fall of the Samurai stretched out!