Japan would seize control of German Micronesia in the fall of 1914, but Japanese interest in the region goes back centuries further. This week: how did Japan get from disinterest in the nebulously defined ‘Southern Seas’ to active military operations to take control of them?

Sources

Hezel, Francis X. Strangers in their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands.

Peattie, Mark R. Nan’yo: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945.

Ruegg, Jonas. “Mapping the Forgotten Colony: The Ogasawara Islands and the Tokugawa Pivot to the Pacific.” Cross Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 23 (June, 2017).

Images

Transcript

When we tell the story of Japan’s colonial ambitions and overseas expansion, we tend to focus on places on or near the Asian mainland: Korea, Taiwan, and so on. And there are good reasons for this–those histories remain very current and important for understanding relations between Japan and its neighbors today, as well as being very central to the narrative of Japan’s imperial history.

But that focus can leave behind some important parts of that history, and today I want to add a bit to the story of Japan’s overseas expansion. We’re going to start taking a look at Japan’s imperial presence in a rarely discussed region of the empire: the Nan’yo, a broad term just meaning “Southern Sea” in Japanese.

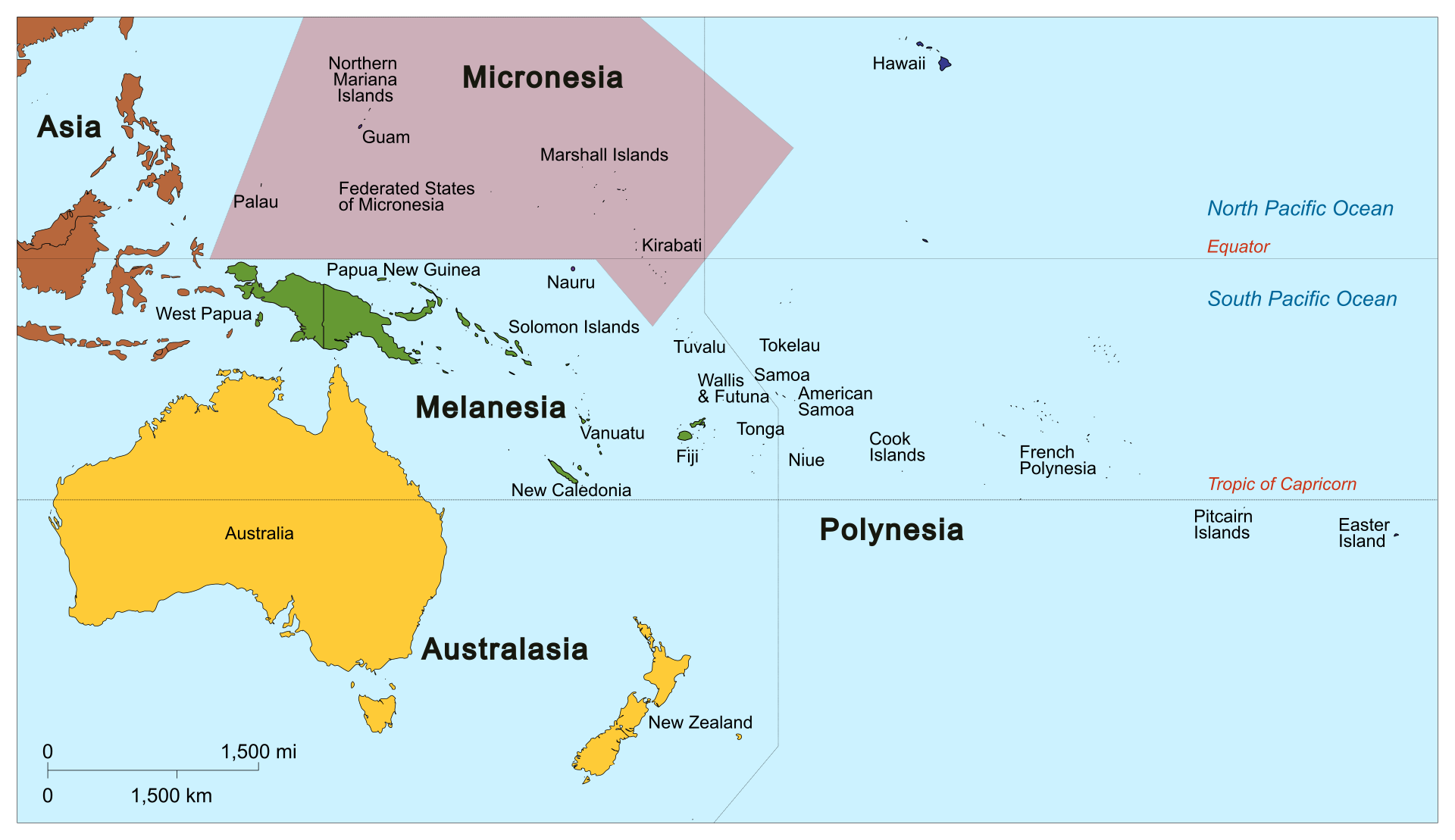

The very broadness of the term shows how loosely this region was defined during the imperial period, but broadly the “Nan’yo” covers the region of Micronesia–the various island groupings in the Western Pacific, spread across the seas north of Indonesia, east of the Philippines, and of course south of Japan. Specifically, these would be the Marshall, Gilbert, Caroline, Mariana, Volcano, and Bonin Island chains. And don’t worry if your geography in this region is a bit shaky–I’ll put some maps up on the show notes, and at any rate my plan is to write this with the assumption that you’re not actively looking at a map or that familiar with the geography.

Anyway: this was a region of the world that, prior to the imperial period, was essentially unknown in Japan. The overseas trading networks of earlier eras had never reached that far south, and of course for 200+ years during the reign of the Tokugawa shoguns the construction of deepwater vessels large enough to intentionally reach those islands was banned by law.

Japanese sailors had reached as far south as the Bonin Islands in the early Tokugawa years. In 1675 the Nagasaki-based captain Shimaya Ichizaemon reported to the shogun Tokugawa Ietsuna that he had found a collection of islands “as large as the province of Sado” 300 ri (about 1,170 kilometers, 727 miles) to the south of Hachijoujima, the largest island in the chain off the coast of what’s now Tokyo. Shimaya had been hired to chart the islands after a crew of shipwrecked sailors had washed up there a few years earlier and then made their way back to Japan; he was one of few captains who had experience sailing before 1633, when the shogunate’s prohibition against deep sea voyages went into effect. Thus, he could do the kind of astral navigation out in the deep ocean required to reach a place like the Bonins.

Apparently he was not very good at sizing landmasses, though; Sado Island in the Sea of Japan is 330 square miles/850 square kilometers, where the total area of the Bonins is 32 square miles/84 square kilometers.

Shimaya’s report on the islands was not promising. They were uninhabited, which is where the name Bonin comes from–it’s a corrupted reading of the characters for Munin, as in ‘without people.’ Other than that, he made observations of the cultivatable land on the islands (there was very little) and of some of the local species before returning home. Hopes that the islands represented the location of the fabled “Kingouto”, or “Island of Gold”, to the southeast of the Japanese mainland proved unfounded.

These less than promising reports meant that for several centuries, the islands were paid little mind by the Tokugawa shogunate. Indeed, the ship used for Shimaya’s expedition would be dismantled in 1679; Shimaya himself would write a treatise on astral navigation, but would never go back to the deep ocean.

The Bonins would pop up occasionally in the social discourse going forward; for example, during the agrarian reforms of the shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune in the early 1700s, there was brief discussion of the Bonins as a potential source of new animal and plant species (and thus new agricultural innovations and wealth for the shogunate). However, when Yoshimune ordered a new expedition to the islands in 1722, officials on Hachijoujima (the island from which the expedition would be launched) found there were no sailors willing to participate in it.

The most prominent appearance of the Ogasawara islands in the public discourse of the time was probably in 1728, when a ronin, or masterless samurai named Ogasawara Sadayuki put in a request with one of the two machi bugyo, or city magistrates, of Edo.

That city magistrate’s name was Ooka Tadasuke–we’ve talked about him before back in episode 273, as he’s a famous guy in his own right. Anyway, Tadasuke received a request from Sadayuki that the shogunate recognize his familial claim to the Bonin Islands, which he said had been given to his distant ancestor Ogasawara Sadayori by no less illustrious personages than Toyotomi Hideyoshi and later Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Sadayuki claimed his ancestor Sadayori had resided on the Bonins in the late 1500s, and that he would lead a private expedition to settle and reclaim the family “fief” there. Ooka Tadasuke ultimately gave the whole affair his permission, but the whole thing proved to be something of a disaster. Ogasawara and his advance party would leave on an advanced expedition to the islands in 1730, but they were never seen again after departing their port of origin (Toba, in what’s now Mie Prefecture).

The Ogasawara family was later stripped of its samurai status alongside a proclamation that their claim was falsified–which it almost certainly was, given that the documents Sadayuki had produced of his ancestor’s voyage there contained references to things like fur seals that don’t tend to appear on subtropical islands.

The islands remained on Japanese maps–indeed, in the 1780s another shogunal official, Hayashi Shihei, suggested that the islands be settled as a protection against Western imperialism: “All of the ten [major Bonin] islands have bays and plains where people can live. They can grow the five grains, and since the climate is warm, exotic things can also be cultivated. Therefore, we should secretly relocate people to this island in order to let them grow trees and build villages and engage in fishery and forestry. Once we have established a productive new province, we will create a regular sailing connection and sail there three times a year to collect the products. The cost for the construction of ships will be compensated with one voyage.”

This is a somewhat rosy estimate of the value of the islands, but at any rate the proposal went nowhere; more conservative elements of the shogunate who wanted to reinforce the existing prohibitions on overseas voyages or contact with the outside were ascendant in the 1790s, and Hayashi ended up under house arrest until his death in 1793.

A similar plan was advanced by the scholar Toujou Kindai in 1843, who advocated that, in response to growing Western empires in Asia and the threat they presented to Japan, the Bonins should be settled and incorporated into Japan itself. Once again, the plan went nowhere, and Toujou was ultimately banished from Edo for encouraging violation of the seclusion policy.

It wasn’t until 1862 that Japan, in the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate, made its first foray proper into the foreboding Nan’yo. By that point, American whalers, drawn to the Western Pacific by the substantial “Japan grounds” of whales–see episode 438 for that–had settled on the Bonins. Their community wasn’t much–just a few harbors with support infrastructure for whaling expeditions–but it represented the first meaningful attempt at settlement on the islands.

By 1862, the Tokugawa shogunate decided to contest this claim–the ongoing crisis with the foreigners triggered by the forced opening of Japan and the unequal treaties had finally led to serious acceptance among some sectors of the shogunate of a plan for expansion into the Bonins.

In 1862, a small collection of colonists–led by none other than Oguri Tadamasa, the focus of episode 463–arrived in the Bonins and declared it Japanese territory. Their claim, Oguri said, dated back to the ill-fated expedition of Ogasawara Sadayuki, which is why you also see these called the Ogasawara Islands sometimes.

I guess ultimately he did get his fief, from a certain point of view. His story was known to be bunk, but it was some kind of grounds for a legal claim to the islands, after all.

Backed up by one of Japan’s only modern warships, the Kanrin Maru, and by a shogunal proclamation to assembled foreign diplomats in Edo as to Japan’s claim to the islands, Oguri and the settlers tried to make a go of it. The group attempted to settle Chichijima, the largest of the Bonins at 23.5 square km (9.1 sq mi).

The settlement effort was, ultimately, not successful–rosy estimates about the economic returns from the settlement proved, well, overoptimistic, and of course the Tokugawa shogunate had far better things to spend money on. The expedition did accomplish a few things; it erected a memorial stele and shrine to Japanese sailors, especially Ogasawara Sadayuki, who were supposed to have died on the islands (and thus spiritually claimed them for Japan), and one of the sailors found an orange tree planted by American sailors on Chichijima (a different variety from the mandarin oranges of Japan, and according to said sailor the new ones “tasted much better”).

Still, man does not live by oranges alone, and after 18 months the shogunate abandoned support for the colony and its residents returned to Hachijojima.

Visions of an empire in the south seas were not abandoned, however–the new government that emerged from the chaos of the shogunate’s downfall shared many of the old one’s concerns about the southern seas.

Which was, in a sense, understandable. Micronesia was one of the last areas on earth to be charted by the European powers, given the complexities involved in navigating the wide open seas it spans. But by the 1870s, that process was drawing to a close, and European empires had already begun to plant their flags in the area.

The Marianas and Caroline islands had been claimed by Spain, which sold off the Marshall Islands to Germany in 1885 as part of the German scramble for an overseas empire to match the other European powers. The Gilberts were claimed by the British, and even the French had laid claim to a few islands in the area (most notably Tahiti).

Notably not consulted in any of this, of course, was the local population. The Bonins were, of course, unpopulated–that’s where the name comes from, as we’ve already said. But the only other island chain in the area for which that was true were the Volcano islands, which we’ll have more to say about in a bit.

All the other chains in the area were populated by groups of Micronesian people. Micronesia–a classification based on linguistic similarities. Specifically, Micronesian languages are a subgroup of what we call Austronesian languages, spread by seafaring peoples who, 3500-3000 years ago, began to sail away from Southeast Asia to new lands. Austronesian seafarers went as far west as Madagascar, as far north as Taiwan, and as far East as Hawaii and Easter Island–it’s a truly remarkable human migration and an incredible feat of navigation and seamanship.

Unfortunately, these local tribes were massively outgunned by the Western fleets that began showing in the area in the 1800s; many tribes ended up signing protection deals with Western powers as a result and were forced into colonial status.

All of this was of course par for the course for Western empires around the world. The logic was also accepted by Japanese expansionists looking toward the southern seas, many of whom embraced the racial hierarchies colonialism was based on–and hoped to prove the advanced nature of the “Japanese race” through subjugating others.

Put simply, the social Darwinist rhetoric of colonialism–that the strong deserved to have power over those who couldn’t resist them–appealed to many in the imperial leadership, who accepted it rather unquestioningly as a part and parcel of what it meant to make Japan “modern” and therefore powerful.

Among these men was Enomoto Takeaki, a man we’ve encountered a few times before. Born in the 1830s, Takeaki was the son of a hatamoto family–direct bannermen to the shogun–who went into service in the nascent navy set up by the shogunate in the 1860s. In 1867, he went on a training cruise that took him through the South Pacific, and the experience apparently gave him a strong interest in the region that would follow him for the rest of his career.

And oh what a career it was. Takeaki is best known for what he did the year after getting back from the cruise; as the shogunate was crumbling in 1868, he took what he could of its fleet and sailed north to Hokkaido, hoping to establish a breakaway pro-Tokugawa regime there. The attempt failed, and Takeaki was jailed–but in 1872 he was released, because the new government needed anyone it could get with experience in naval affairs, and Takeaki seemed like a good choice.

Indeed he was; he’d spend the remainder of his career either working directly on the construction of the Imperial Japanese Navy, or on related projects such as assisting with the colonization of Hokkaido. Takeaki would also use his position in the government, and especially in the navy, to organize for his vision of the colonization of the Nan’yo.

For example, Enomoto encouraged a new settlement program on the Bonin islands in 1875, once again using settlers taken from Hachijojima. This one actually lasted, largely because of more government funding to keep the settlement operational.

He is actually also the man behind the discovery of the Volcano Islands; in 1887, he lent a Naval Ministry charting vessel to an expedition of private explorers (led by the governor of Tokyo, Watanabe Hiromoto), who hoped to find some new territory upon which to hoist the flag. And that’s exactly what they did; the group found the Volcano islands, composed of Kita Io Jima, Io Jima, and Minami Io Jima (the name literally means ‘sulfur island’, which gives you some idea of what’s there). There’s also a fourth island, Nishinoshima, that’s mostly just a giant volcano.

The Volcano islands were annexed two years later, and would eventually develop a small settlement concentrated on Io Jima itself. By the way, the “Iwo Jima” spelling is based on an older system of writing Japanese; it’d be pronounced Iojima, or more commonly ioutou today.

Beyond these settlement programs, Enomoto was a big booster for Japan’s expansion more generally. He’d often give births on Japanese naval voyages through the region to journalists known to be pro-expansion, knowing they would come back and write pieces urging further Japanese exploration and colonization of the area. One such journalist, Shiga Shigetaka, is known for his proclamation in 1890 that, “Every year on the anniversary of the Emperor Jimmu’s accession, February 11, and on the anniversary of his passing, April 3 we should ceremonially increase the territory of the Japanese empire, even if it only be in small measure. Our naval vessels on each of these days should sail to a still unclaimed island, occupy it, and hoist the Rising Sun. If there is not an island, rocks and stones will do. Some will say this is child’s play. It is not. Not only would such a program have direct value as practical experience for our navy, but it would excite an expeditionary spirit in the demoralized Japanese race.”

Takeaki also financially supported the establishment of the Japanese Geographic Society in 1885, which like its counterpart the Royal Geographic Society in London was both an academic institution and a booster for expansion of the empire into the new regions it described–essentially a lobbying group for imperialism.

Slowly but surely, this PR-focused approach to empire began to convince some in Japan that Micronesia represented a valuable source of wealth and a new frontier for expansion of the Japanese empire. The first steps of this expansion were based on trade; in 1887, a cattle farmer from the Bonin Islands, Mizutani Shinroku, took it on his own initiative to fill a schooner with trade goods and head off to Micronesia.

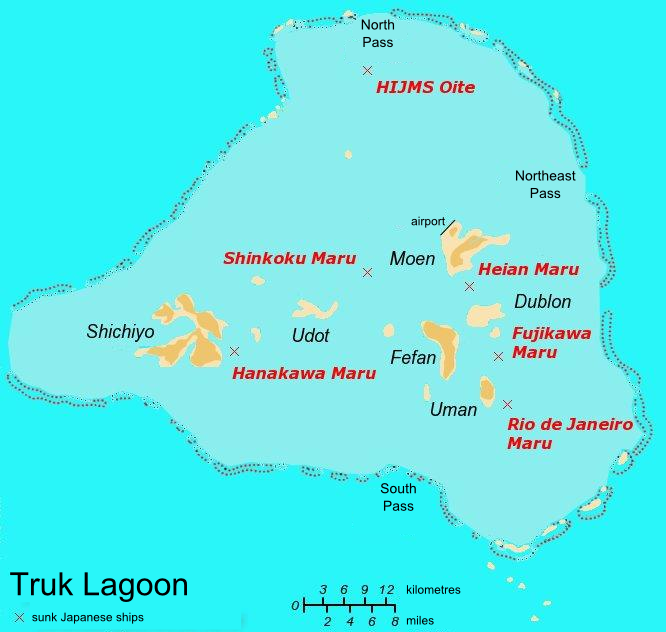

His start was not auspicious; he arrived first at Pohnpei, an island in the Carolines, and after visiting a few of the ports was promptly arrested by the local authorities of the Spanish Empire. Spain had a strict mercantilist policy banning its colonial possessions from trading outside of the Spanish empire, and Mizutani was fined and briefly imprisoned for breaking these rules before being given the boot. This would not discourage him, though; for the next few years he would continue to smuggle in the area, though he would focus on less heavily settled areas like Guam, Truk, Mongil, and Pinglap where there would be less of an official Spanish presence.

Mizutani would eventually organize his own trading company, the Kaitsu Corporation, through which he hoped to expand his economic reach in Micronesia.

This…did not work out the way he’d hoped. Mizutani’s company owned precisely one ship, the Kaitsu Maru, which took its maiden voyage to what’s now called Weno Island. His trading mission with the local villages went well, but on the way home the Kaitsu Maru ran into a storm that forced it up to Hokkaido, where the ship then sank.

Undaunted, Mizutani chartered a new American ship for a second voyage…which promptly vanished during a return voyage from Truk. From this point on Mizutani and the Kaitsu Company vanish from the record, the one presumably financially ruined and the other bankrupt and dissolved.

The fate of Kaitsu is illustrative; many other small Japanese firms attempted to get in on what they saw as a valuable market to exploit, trading Japanese industrial goods in exchange for the local resources of Micronesia. But many, like Kaitsu, failed to find much in the way of returns and found their costs quickly outstripping any revenue.

Indeed, in these early days only two companies were genuinely successful in the region, and only then because they had a LOT of capital invested in making them function at all. These were the Nan’yo Boeki Hiki Goushigaishai (Hiki South Seas Trading Company Limited) and the Nan’yo Boeki Murayama Goumeigaisha (Murayama South Seas Tradign Company, Unlimited). Both firms had substantial financial backing–Hiki, for example, was named after the wealthy landowner Mitsumoto Rokuemon, who had been born in Hiki village in what’s now Wakayama Prefecture. Mitsumoto’s money was what allowed Hiki to operate a fleet of four vessels focused on commercial and agricultural business in the Marianas and Caroline islands.

Neither company made substantial money, however; they just had enough coming in to avoid falling too far into the red.

Conditions began to change, however, in 1898, thanks to events on the other side of the world–the United States ended up going to war with Spain to “liberate” one of Spain’s last remaining colonial possessions in the Western hemisphere, the island of Cuba.

The Spanish-American War, as it’s known, was a crushing defeat for the Spanish Empire and a real indicator of the growing power of the United States on the world stage. More importantly for our story, Spain didn’t just lose Cuba–the US Navy also led a seizure of the Spanish Phiilippines, and in the eventual peace negotiations Spain also ceded the island of Guam to the USs, square in the middle of Micronesia.

The next year, the Spanish government decided to get out of the Pacific game altogether, and sold its claim to the Marianas and Caroline islands to Germany just as it had with the Marshall Islands more than ten years earlier.

The government of Kaiser Wilhelm II was, for its part, eager to expand Germany’s overseas empire, which it saw as a vital part of its competition for prestige and power with other established European states (particularly France and the United Kingdom).

However, those of you skilled with geography will note that Germany is quite a ways away from the Asian side of the Pacific, and those with a background in European history will also know that unlike Spain Germany does not have much of a history as a naval power.

In the aftermath, German firms, most notably the Jaliut Trading Company, tried to move into the region, but they found that the more established Japanese companies already had substantial footholds in the area–having built them illegally under the noses of the Spanish.

The result was an ongoing conflict between Japanese merchants in Micronesia and German ones–whose positions were far weaker, but who enjoyed the backing of the German authorities sent to govern the area.

Those authorities could prove useful allies; for example, one company operating on the island of Palau had its legal claim to lands purchased covertly under Spanish rule challenged by the German governor of the island, who stripped the company of part of its property–the resulting legal battle between the German and Japanese Foreign Ministries was not resolved before the start of World War I.

More spectacularly, the Hiki trading company was the focus of an operation by German authorities who–correctly–suspected that the company was smuggling liquor into the islands. Germany, like quite a few other colonial governments, made a lot of money off of a state liquor monopoly in its territories–a product that, of course, produces its own demand in a lot of ways.

Hiki’s operation on Truk–14 businessmen and farmers–was raided on New Year’s day 1901, as a German frigate entered the harbor and disembarked marines that surrounded Hiki’s offices. Searching the premises at the order of the local German officials, the soldiers found liquor and weapons, and promptly arrested all the Hiki employees. A few days later they were expelled and banned from ever returning to German territory–an order they, of course, immediately ignored by setting up a shell company to hide Hiki’s continued economic involvement in the region.

Still, the Germans were never really able to stop the Japanese economic encroachment into Micronesia. By the 20th century, Japanese trading interests in the region were simply too embedded–those links were physically maintained by large numbers of Japanese men who had come to the islands. These men–and they were overwhelmingly men–formed the backbone of Japanese economic operations on the island, and often lived among the locals and maintained good relations with their political leaders, though they pointedly remained unassimilated. That relationship proved hard to dislodge.

Let’s look at an example: the life of one Mori Koben, born in Kouchi city in what’s now Kouchi Prefecture in 1869. He was the well-educated son of a samurai family, and like many others with that background became interested in politics.

Specifically, he ended up joining the Freedom and People’s Rights movement and becoming an active member of the Jiyuto–and was a part of the plot known as the Osaka Incident which we covered last week.

Mori was only a minor (all of 14) when the incident took place, and was serving as an aid to one of its ringleaders, Oi Kentaro. Because of his youth and tangential involvement, he was released–but found this treatment infantilizing, and so hatched a cockamamy plan to steal incriminating evidence against Oi from a courthouse. This plan was foiled in short order, and did net Mori the prison stay he seemed to be after.

After his release, Mori moved to Tokyo and fell in with some of the crowd orbiting Enomoto Takeaki and advocating for Japan’s expansion south. He was swept up in the romanticism of the idea–like many Jiyuto types, he saw no contradiction between advocating for enlightened liberalism in Japan and empire abroad, and in fact saw the two as inextricably interlinked. Full of a desire to spread enlightened Japanese masses to the benighted peoples of Micronesia (whom, of course, he did not ask to see if they actually wanted this) and swept up in a desire for adventure, Mori headed south. Specifically, he came to Truk, an island famed for both the weakness of the Spanish grasp on the island and the ferocity of the locals. There, he befriended a local chief named Manuppis and offered himself up as a military advisor. He quickly became one of Manuppis’ trusted advisors, both out of personal friendship and because Mori was able to bring Manuppis Japanese-made rifles and scores of disaffected Japanese liberals (as well as former supporters of the Tokugawa shogunate) who were disaffected with the homeland and looking for a fight.

Mori’s devotion to Manuppis was such that he literally got part of his own hand blown off in 1896, during an accident while preparing some ammunition. He returned to Japan for a time for treatment, but came back to Truk after only a few years recuperation.

His close relationship with Manuppis in turn made Mori a valuable agent for any firm looking to do business on the island. He worked for Ichiya trading company, and when they went under switched over to Hiki–as well as also taking a brief gig with Jaliut, the chief German firm in Micronesia. The fact that Jaliut offered this to him is a mark of how useful Mori was as an agent–German firms rarely hired Japanese agents in Micronesia because of the longstanding economic rivalry.

As an agent for these firms, Mori would run a small trading house, receiving shipments from his partners, selling them to the locals, and buying in turn whatever his employers wanted from the area. He acted, in effect, as a franchisee for these trading companies, and did quite well for himself out of it.

Mori was so entrenched on Truk that not even the German raids against Hiki Trading company on the island could dislodge him, and he continued to live there (married to one of Manuppis’s daughters, and raising all his kids to identify as Japanese) through the entire period of German rule.

Still, while the story of men like Koben is interesting,it’s worth noting that the Germans never put consistent effort into dislodging Japan from the region because the colony itself was never a particularly high priority–merely, to use the words of the scholar Mark Peattie, a remote trading outpost where Pacific breezes might waft over the Kaiser’s flag.

It was a territory the Germans had purchased not for any strategic reason, but because having a great empire was what great powers did, and nothing said great power like remote colonies far from the mainland. The extent of German investment in the region is made clear by the fact that the entire German colonial government of the region–consisting of over 2000 different islands covering 3 million square miles (7.77 million square kilometers)–was made up of 25 men total. The place was not, to put it succinctly, a priority.

The other reason Japanese economic interests proved hard to dislodge was that eventually, Micronesia did become a worthwhile market for them. Two products proved essential in drawing the eyes of Japanese businessmen more consistently to the south. The first was copra, a fancy term for the hard shell of a coconut. What can you do with these, you might wonder, other than use them to imitate the sound of a horse’s hooves in your whacky surrealist 1970s English comedy sketch film?

The answer is that you can extract coconut oil–which is in turn used in a variety of exciting industrial applications from making soap and detergent to paint.

The second item was fish, because by the start of the 20th century Japan’s population had expanded so tremendously (adding about 10 million people from the start of the Meiji Era to the dawn of the 20th century) that the nation’s own coastal fisheries could not meet the required food needs.

These two things put together were not exactly the mythic isle of gold, but it was, as they say, a living.

Indeed, business was good enough that by 1908, the leadership of the Hiki and Maruyama trading companies decided that they would be far better off collaborating than competing. The two virtually dominated the south seas trade by this time, and if they combined would become by far the most powerful force in Micronesia’s economy–even the German firms in the area couldn’t hold a candle to their market share.

Which is precisely what happened; the two firms signed a merger agreement in 1908, and together became the Nan’yo Boeki Kabushikigaisha, or South Seas Trading Joint Stock Company. That corporation swiftly became the dominant economic force in Micronesia, which had of course been the intent of the merger in the first place.

And with that economic dominion in place, the extension of Japan’s political dominion over the region was, frankly, a bit anticlimactic.

The moment came, of course, with the advent of the First World War in August, 1914. Japan was bound to one of the Allies by the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, and article 3 of said alliance bound Japan to support the UK (and vice versa) if they faced a war against multiple powers. However, in London, there was some hesitancy to ask for Japan’s support–the sense, not unjustifiably so, was that more than a few members of the Japanese government saw the alliance as an opportunity to seize German territory in Asia and were not actually interested in providing meaningful assistance.

Still, concern over Micronesia won out–the islands of the region were just a few days by steam from crucial Allied supply lines from Southeast Asia and Oceania, and just a few months earlier the German Far Eastern Squadron, commanded by the venerable admiral Max von Spee and possessed of two modern battlecruisers (the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau), had sailed into the area. The British had then lost track of them, and that fleet could produce substantial problems by raiding Allied shipping in the area.

And so, by late August, concern over von Spee’s fleet won out, and the UK asked Japan to join the war under the terms of the alliance. The cabinet of Prime Minister Okuma Shigenobu was happy to oblige, and on August 23, 1914, Japan joined the Allies in World War I.

As it turned out, von Spee was not really an issue; figuring correctly that Japan would join the war and knowing he was massively outgunned, he tried to return to Germany via the Drake Passage around Cape Horn. He was able to defeat a small British blocking force off the coast of Chile, but in December ran square into a massive British fleet waiting for him in the Falkland Islands. In the ensuing battle, the Far Eastern Squadron was wiped out, and von Spee himself went down with the Scharnhorst.

All of which meant, back in Micronesia, the newly designated South Seas Squadron of the Imperial Japanese Navy–a big show of force, with a battleship, two cruisers, two destroyers, and six troop transports loaded with marines–was able to sweep through the area with ease. The process by which Japan’s informal sphere of influence in Micronesia would become an empire had begun.