When World War I began, many among the Japanese leadership were hesitant to take advantage of the opportunity to move into Micronesia. What changed their minds, and how were they able to square a colonial government with the idealistic language of the postwar League of Nations?

Sources

Peattie, Mark R. Nan’yo: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945.

Hezel, Francis X. Strangers in their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands.

Tuori, Taina. “From League of Nations Mandates to Decolonization: A History of the Language of Rights in International Law.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Helsinki, 2016.

Pedersen, Susan. The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire.

Images

Transcript

The Japanese takeover of Micronesia during World War I is often treated as inevitable, given the newfound power position of the empire by the dawn of the 20th century. But in reality, the decision to extend Japan’s empire into that region was the result of a great deal of wrangling back in Tokyo during the early days of World War I in the late summer and early fall of 1914.

On the one side were those, primarily members of the navy and their supporters, who saw the islands as a valuable strategic resource. They could serve as bases for the navy to project its power throughout the Western Pacific, in essence serving as a sort of fortification to protect Japan from the south.

Proponents of this strategy in the navy were supported by an array of nationalistic journalists like Taketoshi Saburo (who himself would eventually be elected to the Diet). Taketoshi himself called for the Western Pacific to become “A Japanese Lake” in which the interests of the empire reigned supreme–making the homeland more secure, and of course providing a valuable captive market for Japanese goods as well as allowing for the extraction of natural resources from the islands.

However, not everyone was as bullish on the plan to build an empire to the south. Members of the foreign ministry as well as some members of the navy were deeply concerned about such overt territorial aggrandizement serving to alienate their British allies. They were also concerned about potentially angering the United States–Micronesia lies between Hawaii, by this point a territory of the US, and the Philippines (also a territory of the US at that time). A Japanese occupation of Micronesia, particularly if it was followed by fortifying the islands, could become a major diplomatic issue.

In other words, the more cautious crowd objected to a takeover not out of humanitarian grounds or anything like that, but because the potential downsides for Japanese diplomacy outweighed the benefits.

For the first six weeks or so of Japan’s World War I experience, this cautious crowd–which enjoyed the backing of the foreign minister Kato Takaaki, as well as both navy minister Yashiro Rokuro and his vice minister Suzuki Kantaro–won out and kept the squadron sent to Micronesia to its original goal of pursuing and destroying the German Far Eastern fleet (which unbeknownst to them was already long gone).

And yes, by the way, that is the same Suzuki Kantaro who would, 31 years later, preside as Prime Minister over the deliberations regarding Japan’s surrender in 1945.

However, as these early weeks wore on, the expansionists in the navy and their backers among civilians launched a massive public appeal–editorials in newspapers and speeches in the Diet decrying the failure to take advantage of this heaven-sent chance to expand the empire in a (as they saw it) vital new strategic area.

The result was that the early days of Japanese military presence in the region were a sort of comedy of errors. Two stories illustrate this well.

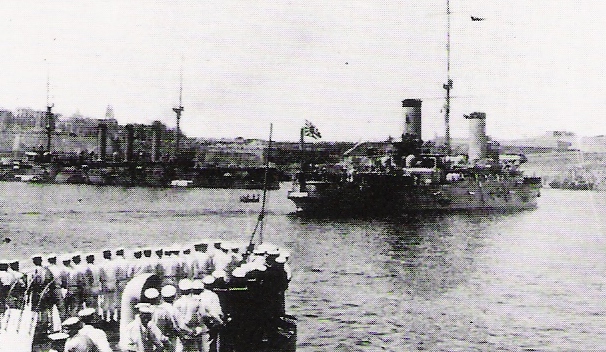

First, we have the initial dispatch of the South Seas Squadron itself, led by Admiral Yamaya Ta’nin. Yamaya had strict orders, initially, to limit himself to driving out the German military presence in the region–which by this point was largely gone, the German Pacific Fleet having bolted for the Atlantic in an attempt to return home. Yamaya, on his own initiative, decided to head to Jaliut Atoll, a part of the Marshall Islands and center of German administration in Micronesia.

His fleet arrived there on September 29th, 1914, and he promptly ordered a landing by marines to take control of the area–a process that went very smoothly, as the small number of Germans on the island had no chance of meaningful resistance and none of the indigenous people had any interest in helping them.

However, when Yamaya radioed back to Tokyo to announce that he’d taken the nerve center of German Micronesia, he immediately got orders to pack up his occupying force and head back to Eniwetok atoll in the northern Marshalls. Navy minister Yashiro was extremely worried about the appearance of territorial aggrandizement on Japan’s part and didn’t want any landings taking place to make it look like Japan was unilaterally seizing territory without checking in with its allies and other regional powers like the US.

However, Minister Yashiro appears to have been overruled, because no sooner did the fleet arrive in Eniwetok than admiral Yamaya received a new set of orders–go back to Jaliut and re-occupy the place. It is a testimony to the weakness of the German presence in the area that this created no problems and he was able to do so smoothly by October 3rd, but still indicative of just how divided the navy, and the government more broadly, was on this issue.

Nor was Yamaya the only one to get confusing instructions. Early in the war, at the request of the British, the Japanese Navy organized a Second South Seas squadron to protect shipping from New Zealand and Australia to Europe–both of supplies and of troops. The admiral placed in charge of this fleet was Matsumura Tatsuo, and on his way to his new fleet in Sasebo he decided to swing by Tokyo to pay respects. First, he went to the Navy Ministry to meet with Minister Yashiro Rokuro, who of course cautioned him on the importance of avoiding any unnecessary appearance of territorial expansion. He was told in no uncertain terms not to even land on a German-controlled island unless it was absolutely necessary, and if he did to get on and off as quickly as he could and under no circumstances to raise a flag or make any other gesture that could be construed as a territorial claim.

Doing so, Yashiro warned, would anger Japan’s allies and create a diplomatic issue that the tiny islands of Micronesia simply were not worth. Thus cautioned, admiral Matsumura made his way to his second stop, the offices of the Japanese Naval General Staff responsible for planning the fleet’s actions. There, in meetings with senior admirals and the vice chief of staff for the navy, he relayed his instructions–which were promptly mocked by basically everyone he talked to. Why shouldn’t Japan pick up some new territory for its troubles in the war, they said? The empire should have something to show for its efforts, and after all it was the empire the navy served, not Japan’s allies. Besides, they said, many of the islands of Micronesia were strategically valuable or rich in useful resources like phosphates.

Based on his private writings, these arguments were far more compelling for Admiral Matsumura, and indeed they proved to be so for most people–cautioning about potential diplomatic issues was not quite as easy a sell as “here’s this easy land to seize that’s just waiting for us.”

In the end, pressure from the navy as well as civilians who were pro-expansion forced the hand of the government, which by the end of 1914 had agreed to land marines on German territories in Micronesia.

While the wrangling over what role Japan would take in Micronesia in 1914 didn’t produce any substantial military setbacks, it did end up badly damaging Japan’s reputation overseas. The public statements by Prime Minister Okuma Shigenobu to the effect that Japan would not seek any territorial expansion as a result of the war seemed rather deceptive when the navy then began landing marines on Micronesian islands and setting up an administrative system to govern them.

That reaction was exacerbated by oen additional factor; after the military operations against Germany in the Far East in 1914, Japan obstinately refused to send any troops to the theaters of combat in Europe–which made the protests that this was all being done in the name of Japan’s alliance with Britain ring a bit hollow. For the remainder of the war, Japan’s commitments would be limited to shipments of arms and supplies, as well as escorts by the navy of convoys coming from Asia–indeed, the only Japanese ship lost in the war, the Sakaki, was torpedoed off the coast of Malta in 1917 while hunting for U-boats. All told, Japan lost about 300 soldiers in the whole war (though that number goes up to 4000 if you include things like serious tropical diseases and the like). By comparison, the UK took well over three quarters of a million losses, and France lost over 2 million.

Given those circumstances, some skepticism around the claims that Japan’s operations in Micronesia were to the benefit of its allies in the war was frankly justifiable, all the more so because after those early months of vaccilation, even the moderates in the Japanese government seem to have accepted that quitting Micronesia after the takeover would be political suicide and so came around to pressuring the other Allies into letting them keep the territory. Thus, by 1915 we have foreign minister Kato–once a voice of moderation–telling the British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey that, on the one hand, he agreed with the stance of the British government that all occupations of land should be temporary and the final terms agreed to at the end of the war, while saying at the same time that, “in view of the very extensive operations in which the Japanese navy has engaged…the Japanese nation would naturally insist upon the permanent retention of all German islands north of the equator.”

Grey himself noted in his reply that Kato was kind of talking out of both sides of his mouth here; how could he agree that these things would be settled at the end of the war but also insist that Japan had to keep the islands. Kato’s response was to dodge that question and merely continue to insist upon Japan’s territorial rights.

Which is more or less where things rested for the next three years. Eventually, the British government agreed to back Japan’s claims to Micronesia, not out of genuine conviction but for two far more political reasons.

First, when in 1917 Germany authorized unrestricted submarine attacks against Allied shipping, the British government requested more assistance from the Japanese Navy in protecting its convoy shipping. The Japanese government agreed–in exchange for a recognition by Britain of Japan’s claim to Micronesian islands north of the equator. This was the exact deal that led to the Sakaki being in the Mediterranean where it was sunk by a u-boat.

Second, the British government was under a lot of pressure from one of its dominion territories, Australia–which wanted to hang on to German islands and colonies south of the equator, most notably Kaiser Wilhelmsland (what’s now the northern part of Papua New Guinea). Ironically, the main reason the Australian government wanted this territory was to ensure it did not fall into Japanese hands–the Australian state at the time was dominated by adherents of the “White Australia policy”, which is…pretty much exactly what it sounds like. For these politicians, hanging on to territory to the north was essential as a buffer for Japanese expansion.

Britain eventually caved in to Australian demands that conquered German territories south of the equator be given to them (they would remain Australian land until the 1970s under a League of Nations Mandate, and eventually a UN Trusteeship). The British government in turn needed the backing of other countries to support this claim–and so cut a deal with Japan that in a final peace conference, each would support the other’s territorial claims.

Thus, when World War I finally came to an end, Japan’s occupation of Micronesia was essentially a fait accompli. Japan had been running a colonial administration on the island for years by this point (about which more in a bit), and had the backing of one of the greatest powers on earth for its claims in any eventual peace settlement.

I think it’s fair to say that Japan’s retention of Micronesia was more or less a foregone conclusion. There is, however, one more interesting wrinkle to the story of how Japan seized Micronesia–a wrinkle created by one of the titanic figures of the age, the American president Woodrow Wilson.

Over the course of his time as president, Wilson went from an isolationist who literally ran in 1916 on the platform of “he kept us out of war” to a proponent of American intervention in the First World War. Wilson was an idealist in terms of international relations–though not in terms of race relations in the US, where he remained a staunch segregationist–and justified intervention on the grounds that it would allow the US and other nations to build a new and more just world order on the ashes of the conflict. Specifically, Wilson called for a postwar world built on his 14 Points–essentially some of the foundational ideas of liberal internationalism as we know it today.

These are things like freedom of navigation and commerce, open diplomacy instead of secret agreements between governments, and some sort of international organization to serve as a forum for discussion between governments. Included in this idealistic vision was the idea that going forward, nations should reject deliberate territorial aggrandizement in war.

America’s influence postwar was such that Wilson could not simply be ignored in the final negotiations at Versailles, France in 1919–but his vision was only half completed. The new League of Nations was very much a part of his vision, for example, but was largely toothless–and of course America itself never joined due to opposition from isolationist Republicans in the US Senate. Similarly, Wilson was able to torpedo any suggestions of outright expansion by the Allies postwar–but was forced to accept a compromise proposed first by General Jan Smuts, the representative of the British dominion of South Africa.

In this compromise, victorious powers would be granted “mandates” by the League of Nations to control territories where the locals were insufficiently “advanced” to govern themselves–a concept grounded, of course, in the racist ideas of social Darwinism and racial hierarchy that still had a lot of currency at the time.

In reality, there was little that separated these mandates from traditional colonies other than the rhetoric of the League–which in many ways was just a re-upping of the idea of the “white man’s burden” to civilize nonwhite peoples which had served as an impetus for 19th century imperialism.

In the case of Micronesia specifically, Japan easily secured acceptance of a mandate for the region, and even inserted into the League of Nations covenant a clause stating that owing to Micronesia’s geographic isolation and economic underdevelopment it should be governed under Japan’s own laws (where other mandates had to at least pay lip service to some separation between the territory and the mandatory power).

Practically speaking, the only way in which Wilson’s idealism seriously impacted the mandate system was his insistence that mandatory powers agree not to fortify their territories militarily–something the Japanese government eventually agreed to as a part of the 1922 Washington Naval Conference so long as its control over Micronesia was recognized.

And so, by a torturous policy of diplomacy ranging pretty much everywhere in the world except for the islands directly affected by it, Micronesia became a mandate of Japan–for all practical intents and purposes, a part of the Japanese empire.

I cannot stress enough, by the way, the extent to which the mandate system was frankly kind of a joke. It was, in essence, colonialism in all but name. For example, mandates were technically subject to the supervision of the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations, a collection of 10 (eventually 11) individuals from different countries who were in charge of ensuring that the mandatory powers were not overstepping their authority and were following on their charge to, in the words of the League of Nations Covenant, uphold the “sacred trust of civilization” by preparing the locals to “stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world.”

Leaving aside the, again, pretty racist assumptions underlining those ideas–which is one hell of an aside–the permanent mandates commission was frankly a joke. For starters, 5 of the 11 member states were mandatory powers themselves, and for the most part the representatives sent to the commission were people who had made their livings through colonialism–retired colonial governors or functionaries, basically.

Susan Pedersen, who has done what’s probably the definitive work on the mandate system, said that the Permanent commission, “”began to resemble a spa for retired African governors.” And frankly, she seems spot on from what I’ve read.

The actual job of the commission members was to review annual reports on each mandate required by Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations (which set up the whole mandate system). Specifically, Article 22 required that, “In every case of mandate, the Mandatory shall render to the Council an annual report in reference to the territory committed to its charge.”

Those reports would come in two waves every year, one in June and one in November–Japan’s Micronesian mandate was one of the June ones. Mandatory governments basically produced a book report on their activities in the mandate based on a questionnaire created by the mandate, which was intended to serve as a policy guide or checklist for colonial administrators. The questions were intended to focus on the “uplifting” of indigenous communities, but the commission members had no ability to actually check the reports they were receiving back.

Each year, the commission would examine the report it received on a mandate and its members would question a representative sent to the commission by the mandatory power. And that was pretty much the extent of the ‘supervision.’

None of the commission members ever went to the mandates themselves, relying on reports from the mandatory administrations. They were rarely critical of anything they heard about the mandates, and when they were tended to mix those criticisms in with compliments about the ‘progress’ of the mandate. As Taina Tuori notes in their work on the mandate system, the primary concern of the commission seems to have been avoiding the perception that they were undermining the colonial administration in front of the natives.

The commission members couldn’t do more than give ‘recommendations’ to mandatory governments anyway, and beyond that their only duty as spelled out in the league charter was to ‘advise’ the league’s governing council regarding each mandate.

Frankly, it’s a system of supervision so weak as to not really be worth the name, and because of that from this point on I’m generally not even going to reference the term mandate and just call Micronesia a Japanese colony instead.

So what happened in Micronesia once it became a Japanese colony? During the years between the 1914 takeover of the islands and the final establishment of the mandate system in 1920, the islands were governed directly by the Imperial Japanese Navy as occupied territory–however, sensitive to the need to convince the other Allies of Japan’s claim to them, the navy’s occupation was fairly light. An initial overwhelming show of force in the form of the two south seas squadrons was enough to cow local resistance or any attempt by the scattered German population to resist Japan’s takeover–most of the Germans were then forcibly expelled. The navy administration then simply replaced the German one, keeping the same laws and regulations in place in the process.

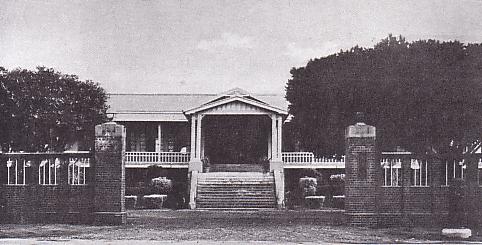

Starting in 1918, the navy began to hand off more control to the civilian government, and in 1920 the new Japanese administration–the Nan’yocho, roughly “south seas office”–took over officially.

The Japanese colonial government of Micronesia represented a pretty radical break from the German administration that had been there previously, which had largely been there just to be there, so to speak. Japan’s colonization of Micronesia was, like that of Germany, intended as a political prestige maneuver, but the Japanese presence was far more active than the old German regime.

As we’ve already covered, the Japanese bureaucracy in Micronesia was far bigger than that of the Germans–950 members, instead of just 25. It was also staffed with people from one of the more unique branches of the Japanese government: the bureaucracy. And remember, this ia a bureaucracy with a very different self-image from the one some of you might have, particularly if you’re American, when you think of the word bureaucrat. Japan’s bureaucrats were and are graduates of elite universities who went into high prestige, high power fields that give them a lot of responsibility and power. In the imperial era (and arguably still now) the professional ethos of the bureaucracy was one of disdainful confidence, one might say–disdain for those with a lesser education, and supreme confidence in their own knowledge and talent when it came to using policy to guide society.

Not for nothing was one of the defining phrase of the imperial bureaucracy kanson minpi–revere the bureaucrat, and despise the people.

And it was from this class of people that the management, so to speak–specifically, from the Takumukyoku, or Colonization Bureau, of one of the most powerful branches of the bureaucracy: the Home Ministry, or Naimusho, which among other things appointed all prefectural governors and ran the justice system.

This organizational structure might not sound like the most exciting thing in the universe, but it had a few important effects on the nature of Japanese rule in Micronesia. For one thing, the bureaucrats picked to fill leadership roles were selected for their knowledge, not of anything related to Micronesia, but of more abstract principles related to law, political theory, economics, and the like. The position of Nan’yo choukan, essentially the colonial governor of the region, was a rotating one that Colonization Bureau bureaucrats would work through on a semi-regular basis, with most serving only 2-3 year terms before moving out of Micronesia permanently. Combined with a lack of knowledge of the local languages and cultures, as well as that haughty attitude so stereotypical of the Japanese bureaucrat, most of the colonial administration had little interest in the Micronesian population beyond questions of how best to extract useful resources from them.

For another, Micronesia itself was subject to some decidedly unusual circumstances in its government. If you’re at all familiar with the colonial history of Taiwan and Korea, you know that both were subject to powerful soutoku-fu, or governments general. These were prestigious and independent colonial governments with substantial backing from two of the most powerful political institutions in imperial Japan: the army and navy.

The Nan’yochou was not like that. That ‘cho’ suffix was the same one used for the governments of Sakhalin Island and the Japanese outpost on the Liaodong Peninsula north of Korea. The governors of these regions were not from the highest ranks of the bureaucracy–which was answerable only to the emperor–but lower ranking members who were appointed by the Home Minister (or, after a reorganization of how the Home Ministry operated in 1929, a separate Colonial Minister). Simply put, the post was low prestige compared to the ‘major’ colonies, so to speak.

Of course, prestige is a relative thing. Within his sphere, the governor of Micronesia had basically unquestioned authority. The regulations for how Micronesia (and every other colony) operated were set up by imperial ordinance, and those ordinances gave the colonial government absolute authority. While in larger colonies like Taiwan and Korea the non-Japanese population was able to push for some limited (though largely fig-leaf) self-government, in Micronesia the colonial bureaucrats were able to successfully argue that the region’s status as a League of Nations mandate meant the area wasn’t even fully under Japanese sovereignty.

This is a bit disingenuous given that the League of Nations Covenant explicitly describes Micronesia as a region that should operate under Japanese law. As a result, the Nan’yochou essentially suspended the Japanese constitution on the islands, removing even its limited guarantees of things like free speech and freedom of religion. The separation of powers on the island was equally nonexistent; the Japanese governor made and executed all laws himself, and while there were colonial courts in Micronesia all the judges were appointed by and answerable to the governor.

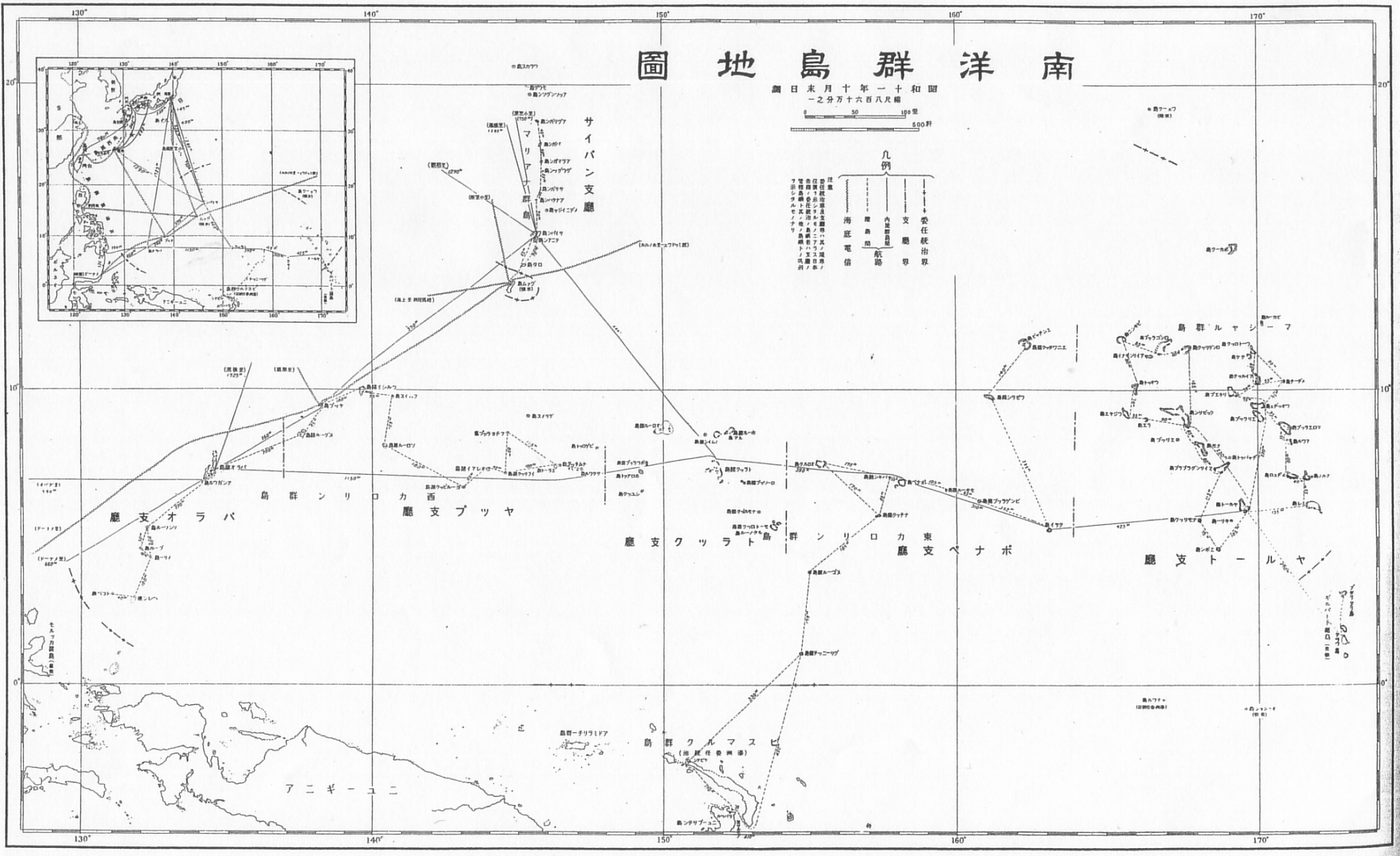

From the governor, all authority flowed downward. The governor’s mansion was on Koror, in the Palau Island chain on the Western end of Micronesia; from there, he would direct the efforts of five branch governments (shichou) led by branch governors who reported to him. Those governments were located on Saipan in the Marianas islands, Yap in the Western Carolines, Truk in the central Carolines, Ponape in the Eastern Carolines, and Jaliut in the Marshall Islands. The authority of the branch governors of these regions was similar to that of the governor himself, with the obvious exception that they were answerable to him.

Beneath these governors were a whole host of bureaucrats, responsible for documenting and managing Japanese rule–setting up school systems, hospitals, and the like to demonstrate Japan’s commitment to the “civilizing mission” given to it by the league of nations, or less charitably to make it easier to mold the locals into useful imperial subjects.

The basis on which this entire imperial structure was built was, of course, the police system–which didn’t even have the minimal restrictions of the Meiji Constitution and its associated laws to keep it in check.

Police were responsible, of course, for enforcing the law–but they were also crucial to the colonial administration in other ways. Japanese policemen collected local taxes, handled the announcement and distribution of new ordinances from the governor in Koror, and even supervised the building of public works. Particularly in some of the more distant islands, the local police station (which might only have 2-3 Japanese police in it) pretty much was the colonial administration, and the Japanese police were quite possibly the only actual Japanese people many Micronesians ever met during colonial rule.

For example, the distant Ratak chain of the Marshall Islands had precisely one police substation for its 16 different atolls (on Wotje), and the 3 cops stationed there were literally it in terms of direct Japanese presence in the area.

Of course, running a government takes more than 3 people even at the local level, and so pretty much from the jump the Japanese police recruited junkei, native constables who would do much of the policework–coopting the locals into colonial government also being a time honored tradition of imperialism.

These junkei were recruited from the population of native men under 40 who passed a physical and had five years of primary education. After a 3 month crash course on the Japanese language and police methods, they were allowed to investigate misdemeanors and do some of the bureaucratic legwork of policing–but were never allowed to rise above their Japanese superiors and couldn’t even investigate Japanese citizens in any legal proceeding until 1929.

The other way in which native Micronesians were incorporated into the ruling bureaucracy was via the system of village chiefs. That position, of course, long predated any form of colonialism in the region, but first the Spanish and then the Germans and Japanese had adopted the practice of making use of these traditional authority figures to bolster their own regime. Under the Spanish and Germans, the traditional Micronesian leadership had largely been left in place, albeit with some curbs (unevenly enforced) to their authority. The Japanese hand, however, was far stronger; ruling families that were unwilling to comply with Japanese directives were replaced with those that were, and a pattern of indirect rule was replaced with one where the traditional village leadership was directly supervised by the local police. The chiefs were, practically speaking, the lowest rung of Japanese colonial bureaucracy, subordinate to the orders of even the lowest ranking Japanese member of the Nan’yocho. They couldn’t even really make decisions independently–largely their job was to enforce directives from above, and they weren’t even fully trusted to do that, as their decisions could be overruled at any time.

You might wonder whether there was any active resistance to what was, after all, a substantially more heavy-handed approach to colonialism than had existed before. The answer is, not really–for two reasons.

First, remember that Japan’s rule over the region was inaugurated with a show of overwhelming force–a large naval squadron steaming through the region landing marines left and right. That force withdrew by the 1920s, but the threat of it was still there; indeed when a rebellion on Palau sparked by the syncretic Modeknegi religion broke out in 1918, it was put down by swift police raids that arrested the founder and most of the leadership.

Beyond this, organized resistance proved a challenge to organize. Micronesia is, as we’ve discussed, a vast territory covering a truly massive expanse of sea–and while its residents do share linguistic and cultural relationships, those relationships were not particularly close. Put in terms of somewhat fancy academic speak, a Micronesian ‘imagined community’ whose members saw themselves as tied together in the sense of a modern country did not yet exist–indeed, it was the shared experience of colonialism that would create that identity, in many ways. But in the 1920s, the absence of a shared framework for thinking about Micronesian resistance–instead of Palauan resistance, or Marshallese Resistance, and so on–meant that a mass movement genuinely threatening to Japanese rule was not yet possible.

Besides, resistance movements like that generally aren’t successful without outside help, and that was hard to come by. Japan’s rule, after all, was recognized by the League of Nations, and Japanese regulations swiftly barred ships from outside powers from entering the region. Technically, this was a violation of League of Nations promises about freedom of navigation through the seas, but frankly most of the League members did not care–their only interest was in telegraph cables running underseas through the region, and as long as those were not interrupted, well, there was not much to worry about.

Only the United States–which did and still does control a part of Micronesia in the form of the island of Guam–ever pushed back against the orders closing the region to outside observation. And that pushback went away when the Japanese leadership promptly guaranteed there would be no interference with American shipping in the area.

Next week, we’ll get into the Micronesian experience under Japanese rule.