This week: the elimination of smallpox is probably one of the greatest medical accomplishments in human history. The vaccine that made it possible, however, was invented during a time of isolation for Japan. So how did the vaccine make it to Japanese shores, and what does that story tell us about public health, the sharing of information, and the nature of society in late feudal Japan?

Sources

Suzuki, Akihito. “Smallpox and the Epidemiological Heritage of Modern Japan: Towards a Total History.” Medical History 55, No 3 (July, 2011).

Janneta, Ann. The Vaccinators: Smallpox, Medical Knowledge, and the ‘Opening’ of Japan.

Images

Transcription

I imagine that these days, if you hear the word smallpox, you don’t have much of a reaction–if you have one at all. The last known natural infection of smallpox was in 1977, and in 1980 the World Health Organization declared it to have been eradicated: the only disease we’ve ever managed to accomplish that with.

But that’s a relatively recent accomplishment; for much of human history, smallpox–a common name for infections of variola virus–was an absolute terror. It’s been with us for basically all of human history; the disease is thought to have first jumped from rats to humans over 10,000 years ago, and we have evidence of infections as far back as Egyptian mummies from the 1500s BCE.

There are several discrete strains of variola virus, which I will not bother you with the names of. The disease’s mortality rate varies a great deal based on the strain, though the most common form (ordinary smallpox) was around 30%. Less common were hemorrhagic strains that were almost always fatal. Regardless of the precise strain, the fact that smallpox can be transmitted by aerial droplets from an infected person meant that it could spread extremely quickly, making outbreaks enormously difficult to contain. The best estimates from the WHO suggest that in the century before it was eradicated, this transmissibility made smallpox an enormous killer–it probably was responsible for about half a billion deaths in the span of those 100 years.

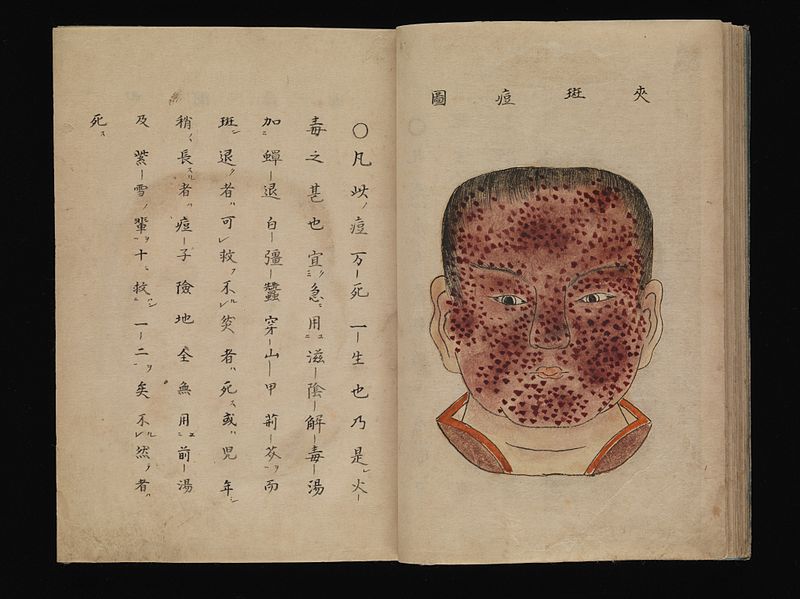

In addition to the usual symptoms associated with viral infections-fever, chills, aches, all that good stuff–smallpox is most readily identifiable by the skin rashes it causes. These look like viral pimples that spread all over the body, hence the name ‘pox’, derived from ‘pockmark’–a pitted mark on the skin. Survivors would find these marks often scarred over after recovery, leaving someone with very visible remnants of their previous infection. Smallpox can also cause a host of other complications, particularly to the respiratory tract. It can also cause blindness if the infection reaches the eyes; it’s estimated that in Europe in the 18th century, one out of every three cases of blindness was probably caused by smallpox infection.

The disease has thus always been a devastating and dangerous one. In Japan, the first recorded smallpox epidemic began in 735 CE and probably killed around 30% of the population (about 1 million people) including several high-ranking members of the aristocratic Fujiwara family. The death toll triggered social chaos–mass migrations of commoners away from infected areas, which in turn triggered massive economic problems caused by labor shortfalls in those places.

The emperor and the court were only able to get things under control by issuing mass tax exemptions and opening up the treasury to pay for public relief–and by establishing several new temples, including Todaiji in Kyoto, to placate the gods against the evil of the virus.

The gods were apparently not entirely placated, however; from 735 to 1204, there were 28 more smallpox epidemics across the country, though none were ever as disruptive as the first.

However, in Japan–and elsewhere–a funny thing began to happen as smallpox became what’s called an endemic disease: one which, thanks to a large enough population, was constantly being passed from person to person and thus never really went away, though more severe outbreaks did on occasion happen. .

By about 800 years ago, Japan’s population became large enough for smallpox to become endemic.

When a disease becomes endemic to a population, that means there’s a large enough number of people that someone is infected basically all the time–there’s enough population to support a constant ‘reservoir’, so to speak, of smallpox.

Most people were exposed at some point, and the survivors, it turned out, never got sick again. We know now, of course, that this is a result of developing antibodies to fight the virus; at the time, all that was known was that if you were infected and survived, you could never get smallpox again.

Which meant the danger of smallpox never really went away; but it also meant that there were always people who had been exposed and were immune in the population, which in turn served as a sort of ‘fire break’ on transmission rates. Given the number of people with immunity, the spread of the virus was always somewhat limited–making it impossible for an epidemic of rapid spread to take place. So on the plus side, no more 735-style epidemics where a third of the population dies–but on the downside, smallpox would always be a concern. It was never going to go away.

The existence of a population immune to the virus due to previous exposure, combined with the high transmission rate of the virus, meant that by the age of the Tokugawa shoguns most of the danger of smallpox was to children.Given how easily the virus spread, most adults were exposed to it at some point–and by definition had to have survived and received natural immunity to reach adulthood.

For example, records from the village of Hida in what’s now Gifu Prefecture in central Honshu show that between 1795 and 1852, smallpox was responsible for an astonishing 735 deaths of children 10 and under; the next highest disease, dysentery, was 217.

For comparison, in the same frame, smallpox killed 38 adults in Hida. More broadly, by the mid-19th century, a child born in Japan had a ⅕ chance of dying from smallpox–and most of them would die before the age of 5.

Childhood exposure to smallpox was thus a literal matter of life and death. There was a pretty substantial cult dedicated to the placating of ‘demons’ thought to cause the disease; folk cures for the disease included everything from pilgrimages to major shrines by family members to red-colored charms and clothing thought to ward away the demons. Children who recovered were even treated to a special celebratory ceremony called the sasayu, essentially a massive family party to commemorate their survival.

By the 1800s, however, these approaches were being pushed out by more modern ones. Doctors like Hashiimoto Hakuju of what’s now Yamanashi prefecture were successfully calling for treatment based on isolation of the infected to contain the disease–and a new idea called vaccination was starting to spread around the country.

The observation that those who caught smallpox once never got it again was, as I’ve mentioned, a pretty obvious one to those dealing with the disease. Before long, it became common practice around the world to expose children to people with mild forms of the disease–hoping that catching and surviving a mild form would give them the best odds of survival long term.

And certainly, the odds were better than just going for it in the wild, so to speak–but even ‘low risk’ exposures were still, well, risky.

In both China and what’s now Turkey, a special approach to this practice called variolation began to develop in the early modern period–that’s more or less the late 1500s. This was a practice of essentially cultivating mild smallpox virus deliberately and storing it for deliberate exposures: in China, the process relied on dried smallpox scabs that were then ground up to be breathed in, while in Turkey the process was an early form of inoculation relying on pus from smallpox victims that was placed under the skin via incision.

We know that Turkish-style variolation had a following in Europe; for example, following descriptions of Turkish variolation gathered by Royal Society fellow Mary Wartley Montagu, the British crown sponsored an experiment on six condemned prisoners in 1722 that seemed to show it as effective in inducing a survivable case of smallpox. Jesuit translations of Chinese medical texts also introduced Chinese ideas on variolation to Europe, though these never developed quite the same following as the “Turkish model”, so to speak, did.

If you’re wondering; Chinese-style variolation did have a small following in Japan, chiefly because one of the biggest proponents of the approach, a Chinese physician named Dai Manquang, trained several Japanese doctors while living in Nagasaki after moving there in 1653. However, his school–known as the “Chinese Fever School” and bolstered by other expats fleeing the civil wars that established China’s final imperial dynasty–never developed a huge following. There was no consensus among Japanese doctors that variolation worked in the way there was among their Chinese counterparts.

The dispute over variolation quickly fell by the wayside, however, because along came a man by the name of Edward Jenner whose discoveries would fundamentally remake our relationship with smallpox and lead, 200 years later, to its eradication.

The English-born Jenner is the one who, in 1798, produced research making a case for what he called vaccination. Jenner was a country man obsessed with livestock, and had noticed that milkmaids who worked with cows infected with what was called cowpox–which produced the same sort of viral pimples smallpox did–could contract that disease themselves. However, cowpox produced far milder symptoms and was never really dangerous to humans, and–and this is the important part–after being exposed to that disease, said milkmaids never caught smallpox.

Jenner thus naturally supposed that there was some sort of immunological relationship between smallpox and cowpox, and tested this by taking puss from a human cowpox victim (Sarah Nelmes) and innoculating a boy named James Phipps with it. He proceeded to catch a mild case of cowpox. Phipps was then exposed to smallpox, but never contracted the disease.

Now, the medical ethics of this are somewhat questionable to be sure, but that’s a whole other podcast. What is very relevant for us is that Jenner’s paper on the subject was groundbreaking. He gave the cowpox a Latin name–variolae vaccinae, to go with the scientific name for smallpox variolae major–and called his new invention a vaccine, from the latin vacca, or cow.

Jenner’s smallpox vaccine was instrumental in remaking our relationship to smallpox, and the wider idea of vaccination is one of the most important breakthroughs in the history of medicine…probably ever? Not an expert on the field but it’s up there for sure.

Why does this matter for Japanese history? Well, news of Jenner’s experiment spread like wildfire across the medical community. Within a year it had been translated in Latin and German editions, and by 1801 there were French and–most importantly for us–Dutch printings floating around as well. Despite Europe being actively embroiled in war while this was going on–the complex wars of the French Revolution, specifically–there was just too much interest in this process to be denied.

From there, news of the invention spread across trade networks and via the colonial empires of the European powers. The greatest challenge was moving live samples of the cowpox virus with which to perform inoculations; for example, initial attempts by the government of Dutch Batavia (what’s now Indonesia) to get the cowpox vaccine to the area failed when the virus died in transport, and so vaccination wasn’t able to begin until 1804. But still–and quite remarkably–it only took about 5 years for both the invention and the actual vaccine to arrive in more or less every region of the globe.

But what about Japan? Well, those of you knowledgable about this period of Japanese history would probably assume that it took a long time for news of this breakthrough to reach Japanese shores. After all, Japan’s trade with the West was tightly controlled–only the Dutch VOC, or East India Company, was allowed a tiny toehold on the island of Dejima in the harbor of Nagasaki, and only then under close scrutiny.

In fact, vaccination actually reached the Dutch outpost in Nagasaki faster than it did the Dutch colonies in what’s now Indonesia–thanks to a weird quirk of the age. Mid-way through the wars of the French Revolution, the Republican government of France would invade neighboring Holland and depose the existing government in favor of a “Republic of Batavia” that was pro-French.

This in turn brought the Dutch into the wars of the Revolution on the side of France, making their ships–including the one a year that handled the run between Nagasaki and Batavia–targets for the other side. And since the other side was the British and their Royal Navy, that was…not a great place to be.

The Dutch East India company needed a fix to keep Nagasaki supplied. They found it by contracting with ships from neutral powers to handle the Nagasaki runs. So, the VOC started an elaborate shell game. Tne of these was the Rebecca, a ship out of Boston. It flew the American flag on its way to Nagasaki, but took that down in favor of a Dutch one before entering the harbor–because the VOC, worried that the shogunate would stop seeing it as useful and expel the company from Japan, hadn’t mentioned anything about that whole ‘invaded by the French’ thing.

They also hadn’t mentioned that the VOC was under the direct control of the Dutch government, because the sense was that the shogunate only tolerated the VOC because it wasn’t a government–and thus had no interests in Japan beyond making money.

Anyway: the Rebecca came to Nagasaki in the fall of 1803, and brought with it news of this new smallpox vaccine–a Boston doctor, Benjamin Waterhouse, was friends with Edward Jenner and had introduced vaccination to Boston literally the year after it was invented. From there, a member of the Dutch staff on the island–Hendrik Doeff–mentioned the invention to one of the hereditary class of Dutch to Japanese interpreters in Nagasaki, Baba Sajuro. Sajuro’s record of the conversation reads: “A ship had just come into the port of Nagasaki bringing a book which Doeff examined. He told me they had recently succeeded in taking lymph from a cow and planting it in a person. This method had a better success than the jinto method (human pox, or variolation) which uses smallpox lymph taken from people.”

Baba Sajuro and Hendrik Doeff are names that are always linked in the history of vaccination in Japan; Sajuro in particular would be instrumental to the history of vaccination in Japan, but only because of a rather odd twist of fate on the other end of Japan.

As we’ve talked about before, by the early 1800s the Russian Empire had begun to push into East Asia–and that push brought Russia naturally into conflict with Japan as Russian forces ran up against Japanese territory and the closed country policy.

Russian merchants had reached the northern island of Hokkaido–under Japanese influence, though not directly a part of Japanese territory–as far back as the 1770s, but as the years went on Russian policy in Japan became increasingly aggressive.

In 1804, a Russian warship, the Nadezshda, arrived in Nagasaki–it was a part of a Russian expedition around the world that had been dispatched from Kronstadt the previous year. The commander of the expedition, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, was in charge of 88 crewmen, four Japanese castaways who had ended up in Russia, and most importantly a letter and gifts from the tzar saying Russia was requesting friendly relations with Japan and a trade agreement.

The Japanese knew they were coming (the Dutch had forewarned them) but not the contents of the request–which ended up taking months to convey, because the tzar’s letter was in Russian, Manchu, and a version of Japanese so garbled by the castaways that it was nigh unintelligible. It was only when one of the Russian crewmen (a ship’s doctor) who spoke some Dutch rendered the requests into that language for the Japanese translators that the meaning could be conveyed.

When it finally was, the Russians were confined to a warehouse in Nagasaki while the request was forwarded to Edo. In March, 1805, the answer came back: absolutely not. The shogunate refused both the request and the tzar’s gifts, and ordered the Russians away.

Rezanov was furious, and determined to avenge this slight against Russia’s honor. On his way out of Japan he used the Nadezhda to scout the defenses of the northern part of the country–what’s now Hokkaido, Sakhalin Island, and the Kuriles. There was a Japanese presence there, intended to maintain control of the local Ainu indigenous population–but Rezanov noted it was a fairly minor one with few defenses that could withstand Russian attacks.

He instructed a pair of officers stationed in the Pacific, Nikolai Khvostov and Gavriil Davydov, to launch retaliatory attacks–which they promptly did, starting in October of 1806. Their forces raided Japanese outposts on Sakhalin as well as Iturup and Urup in the Kurile Islands, raiding and burning Japanese possessions as well as taking Japanese living on the islands prisoner.

The raids had no formal authorization from the tzar, and both men were actually eventually court martialed for them–but what matters for us are the captured Japanese prisoners, to whom we will return in a bit.

But first: news of the raids was met with understandable rage in Edo–particularly given that two ships owned by the shogun had been destroyed in the fighting. In the aftermath, the Tokugawa shogunate began to pay far more attention to its northern frontier (see episode 372 for more info about that if you’re curious), but also to step up its efforts to learn about the world outside of Japan proper.

In 1808, the shogunate set up in the Asakusa neighborhood of Edo a new Bansho wage goyou, or Bureau for the Translation of Western Books, to facilitate learning about the situation outside of Japan. The Bureau was charged with facilitating translation of all Western books–but given that the main connection to the West was still via the Dutch on Nagasaki translators of that language were in particular demand.

Back in Nagasaki, Baba Sajuro was becoming uniquely qualified for this kind of work. Ordinarily, Japanese policy required that the Dutch, especially the outpost chief, be rotated out on fixed intervals–that way, they would never have a chance to learn Japanese, and thus remain dependant on translators provided by the shogun. But the Napoleonic Wars prevented that rotation from taking place; as a result, Hendrik Doeff and Baba Sajuro had struck up a friendship, and among other things Doeff was now teaching Sajuro other, non-Dutch European languages like French and German. This made him a perfect candidate for the new bureau, to which he was posted in April of 1808–Hendrik Doeff’s own diary celebrates the achievement of his friend.

Once in Edo, Baba’s talent for languages resulted in his being allowed access to one of very few Russian language teachers in the country–a Japanese sailor named Daikokuya Kodayu who had been shipwrecked on the Russian Pacific Coast and taken to St. Petersburg before eventually being returned. And that in turn meant that when the whole Russian situation took yet another weird turn, Sajuro would be at the forefront of what came next.

As we already covered, those 1806 raids were not authorized by the tsar and the officers responsible were punished. But apparently nobody in the Russian government realized exactly how much bad feeling there was over them, because in 1811 a captain named Vasili Golovnin was ordered to conduct an exploratory mission of the Sea of Okhotsk and the Kuriles. He put ashore on Kunashiri Island just northeast of Hokkaido, and the local Japanese garrison promptly arrested him and his entire shore party, bound them, and sent them to Matsumae–the castle of the Matsumae clan who ruled Hokkaido on behalf of the shogun.

Golovnin’s ship, the Diana, still had some men aboard, and the new commander decided to head back to Russia. There he’d collect Japanese prisoners taken by the Russians–including the ones from the 1806 raids–and offer to swap them for Golovnin and his men. In December, 1812, the first batch of Japanese prisoners was returned to Hokkaido.

Among their number was one Nakagawa Goroji, previously a merchant working in the fishing trade that was a key part of Hokkaido’s economy at this point. Nakagawa had been held in Siberia for six years, and during that time had become a physicians assistant in Irkutsk helping with, among other things, the cowpox vaccination. When he was returned to Japan, he had on his person a small, Russian-language government publication explaining the benefits of vaccination over variolation as well as how to perform the procedure.

Neither the text nor Nakagawa himself was of immediate interest to the Matsumae clan or the officials of the shogun in the far north–both tended to view returned castoffs with some suspicion, and at any rate none of them could read Russian. The book was promptly stuffed into an archive in Matsumae castle, and Nakagawa interrogated first in Matsumae and then in Edo about his experiences.

Meanwhile, Baba Sajuro was informed in early 1813 that he was going to Matsumae with another employee of the Bureau (a mathematician), to negotiate with the Russians regarding the release of captain Golovnin. In the meantime, he was to use his Russian skills to learn as much as he could from the captives before they were let go.

Golovnin at first found the two annoying–after all, he was their prisoner, and now being asked to play geography and language teacher–but eventually came to find the enthusiasm of the two men rather endearing. Baba Sajuro in particular made a very good impression, and Golovnin eventually helped him put together a primer on Russian grammar.

And then came the fateful moment. Baba was told about an archive of captured Russian texts in Matsumae castle, and began to look through it. There he found Nakagawa’s vaccine primer, and took it to Golovnin, who explained what it was. Baba would later recall:

“The book was about how to plant lymph. I remember clapping my hands and thinking: I heard about this [method] in Nagasaki several years ago, and now I am hearing about it again in this distant land of Matsumae. Not only that, I am also able to see the book in the original Russian language.

I was delighted and asked…for permission to take this book to my inn. Every day I took this book to the Russian residence and asked [Golovnin] about its content. At the time, I had had only three or four months to learn Russian, so it was not easy to understand what he was saying. This took a great effort. After many days I grasped the general sense of the book.”

Before Golovnin left Japan in October of 1813, the two had compiled the start of a translation of the text. But it was only a start; Baba later recalled that, given his rudimentary knowledge of Russian and without Golovnin to ask questions of, he could only understand about 1/3rd of the text.

So Baba made the decision to lay the text to the side while he focused on improving his Russian. He would not return to it–or indeed, from what I’ve seen, discuss it substantially–for six years. It might seem strange to you that Baba would just leave behind a project with such obvious and immediate value–particularly because, in his own recollections, he spends only a single sentence on that decision. There’s a few factors at play, though, that I think help us to understand why he would do that.

First and most directly–speaking as someone who has done some translation work in the past, though I would never call myself a translator since I have no talent for it at all–I do understand his reasoning in terms of language. If you’re just a few years into learning a language, translation can be fun as a project to help you build your understanding of a language, your ‘mental map, so to speak, of how ideas and concepts correspond to those in other languages you know. It’s a useful exercise, but the goal of translation is to produce something anyone can use, and that is WAY more demanding, particularly when moving between languages as different as Russian and Japanese. So if Baba wanted to produce something any doctor or official could use to understand why vaccines worked and how to do them–as opposed to just some fun practice for his Russian–I kinda get it.

Second, Baba was hoping that before long, a Dutch-language book would arrive in Nagasaki with information on vaccination. He could then convince the local officials to buy it off the Dutch; given the higher levels of familiarity with that language in Japan, such a text would make life a lot easier. That’s not an unjustified hope; as we’ve established, Jenner’s original text was translated as early as 1801. But, for reasons unknown, no copies of it or any other work on vaccination arrived in Japan during Baba’s lifetime.

But there’s more at play here than simply wanting to produce something useful or hoping for a Dutch text to make life easier. Baba was one of a privileged few scholars in the employ of the shogunate to study the West, but his access was still tightly controlled. The shogunate controlled the access to texts of rangakusha–scholars of “Dutch Studies”, as it was called, since most knowledge of the West came by way of Dutch-language texts. That access was usually restricted to ‘official’ topics, and Baba’s work on smallpox was not by any means official. Indeed, technically just having the pamphlet was a violation of Edo period laws around owning foreign texts. Those laws were admittedly vague and highly uneven in their enforcement, but in a certain sense that made things worse–it was kind of a guessing game who Baba could go to for approval of his project. And there wasn’t a procedure for him to ‘report’ the translation or the text either, despite the fact that everything he was working on was obviously beneficial to the shogunate.

This rather odd position helps explain, I think, Baba’s reluctance to speak much of his work on the translation or to talk about it with anyone else–and speaks to one of the fundamental issues created by the rigid and tightly controlled social order of the Tokugawa state.

Ultimately, what got Baba to return to the project was yet another incursion into Japanese waters by a Western ship. On June 17, 1818, an English ship, the Brothers, sailed into Uraga on the edge of Edo bay. The captain, Peter Gordon, was sailing to Okhotsk from Bengal, and wanted permission to swing by Japan on the return leg of the trip to sell cargo. Once again, Baba Sajuro was dispatched alongside his previous travel companion Adachi San’ai, with a twofold mission. First, they were to politely but insistently pump Gordon for information regarding goings on outside of Japan–particularly the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which had come to a conclusion just three years earlier with Napoleon’s dramatic defeat at Waterloo. Second, they were to politely but firmly tell Gordon to go the hell away.

Gordon described the encounter with the two men as pleasant, but mostly focused on how impressed he was by the command Adachi and Baba had of foreign languages (the conversation apparently took place primarily in Dutch, with which any Japanese specializing in “foreign knowledge” at this time would have been very familiar). Far more interesting is what Baba had to say about their time together: “In the summer of Bunsei 1 [1818], when a British commercial ship arrived at Uraga, I was ordered to board the ship for a thorough inspection. At the time, the captain took out a book, a glass bottle, and a glass plate. He explained “that the glass bottle contains cowpox scabs, the glass plate is a tool for grinding them; and the book explains the vaccination method. I have no other gift so I will present these to you.” But I had to decline them.”

Why did he have to decline them, you might be wondering? Well, because the laws Baba operated under forbade him from accepting gifts from foreigners, particularly those who had come to the country without approval. Otherwise, it might be taken as encouragement of their endeavors.

So Baba was forced to leave behind basically everything he needed to figure out the vaccination process. But the experience stirred him to return to the Russian text, and with six years of practice he was far better equipped to translate. As he put it in the preface to his translation: “As thought about it afterward, I first heard about this from a Dutch person in Nagasaki. I then obtained a book from a Russian in Matsumae. Now in Uraga an English man wants to give me a book and scabs. I had heard about this vaccination three separate times. How odd. So I again took up the translation of the Russian book. No one had translated this book before this time. I was the first to do so. Therefore, there may be many misunderstandings and mistranslations. I hope that people who come after me will correct it.”

The final translation was called Tonka Hiketsu, roughly something like “secret methods for the prevention of smallpox.” Baba’s preface to the text shows that by the time he finished the translation in 1820, he was utterly convinced that smallpox vaccination worked and could save countless lives.

However, the text was never officially published–we don’t know why, but quite possibly because once again it wasn’t an “official” project for Baba while he was at the bureau.

Supporting that theory is the fact that he signed it with his childhood name (Sadayoshi) and referred to himself as an official of Nagasaki rather than Edo (where the Bureau was located)–perhaps to distance himself a bit from an unauthorized project.

Baba completed a manuscript translation in 1820, and two years later died suddenly at the age of 35. We do not know the cause of his death, and so far as we know prior to his passing he never shared his translation with anyone.

However, we also know that the manuscript he created continued to circulate after his death, though it was not officially published until 1849–we have evidence, for example, of a copy of the manuscript being sold in Nagoya in the 1830s, about which we’ll have more to say next week.

Still–Baba’s death, and his secrecy around his work, meant that progress spreading knowledge of vaccination around Japan was going to be limited. We’ll see that conversation continue–leading to the eventual start of Japan’s first, genuine, national public health campaign–next week.

That’s so interesting you’re going over this since I recently finished an anime called Hidamari no Ki, based on Osamu Tezuka’s manga, whose central plot is based around Tezuka’s real great grandfather Ryoan Tezuka trying to set up a bakufu-approved smallpox vaccination clinic in Tokyo during the Bakumatsu. His biggest enemies are the traditional medicine practitioners who want to ban western medicine and the people spreading rumors that the vaccine will turn you into a cow. Ryoan’s foil is a fictional Fuchuu shishi who gets involved with Saigo Takamori. You should look into it. It covers all the great historical events of the bakumatsu like the cholera outbreak, the Ansei Purges, and the Ansei Earthquake.