This week, we’re looking at the implosion of the Japanese New Left with a focus on the factional conflicts of the Zengakuren. How did a student youth movement end up divided into 20+ factions, the two largest of which engaged in a multi-decade war of assassination and street violence against each other? And how might that be connected to the general decline of Japan’s left-wing opposition more broadly?

Sources

Andrews, William. Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture from 1945 to Fukushima.

Dowsey, Stewart, ed. Zengakuren: Japan’s Revolutionary Students

Shimbori, Michiya, et al. “Japanese Student Activism in the 1970s.” Higher Education 9, No 2 (Mar, 1980).

The official websites of both the Chukakuha (bonus in English) and Kakumaruha

Images

Transcript

One of the rather odd features of postwar Japanese history is the rather meteoric trajectory of the New Left. As we’ve seen, postwar leftist groups that defined themselves at least in part by their opposition to more traditional left-wing organizations like the communist party or labor unions blossomed in the 1960s. But, if you’re at all familiar with the political landscape of modern Japan, you’ll also notice that this surging New Left–which once upon a time, could call on enough support to make Tokyo look like a warzone during its battles with the police–is today pretty much gone.

That begs one hell of a question: where did they all go?

And this week, we’ll wrap up our look at postwar left-wing radicalism with a discussion of that exact question, with a particular focus on probably the most iconic of the new left groups, the Zengakuren.

As a quick refresh, the Zengakuren was originally founded in 1948 as a vehicle for influence by that most old left of organizations, the Japanese Communist Party. The thinking was that the Zengakuren–short for Zen Nihon Gakusei Jichikai Sou-rengou, or All Japan Union of Student Self-Governing Associations–could build up a following among the various jichikai of Japan’s universities, a combination of student government and student union.

These jichikai in turn enjoyed comparative autonomy in the immediate postwar era thanks to educational reforms imposed by the postwar Occupation, and thus could form a powerful support network in favor of the Japanese Communist Party.

Over the course of the 1950s, however, the Japanese Communist Party lost control of the Zengakuren due to both its own missteps (most notably a deeply unpopular attempt at revolution in 1952) and a wider disillusionment with the global communist movement caused by revelations of the crimes of Stalinism. As a result, the Zengakuren was overtaken by a faction of students calling themselves the Bund (after an early Communist group founded by Karl Marx). As that name might imply, the Bund were not opposed to Marxism as an ideology, just to the Japanese Communist Party and the modern communist movement.

The Bund’s dominance of the Zengakuren, however, would not last long–in the aftermath of the 1960 protests against the US-Japan Security Treaty, the Bund fragmented over disagreements regarding why the protests had failed to either a) stop the security treaty itself or b) form the basis of a longer term successful left-wing movement in Japan.

As a result, the Zengakuren itself split into a series of competing factions. And up until this point, whenever we’ve talked about the Zengakuren and gotten to this point, I’ve said something like “I won’t trouble you with the names of all the factions because they’re too complicated.” But, my friends, we have arrived at that fateful time; now is the moment for us to dive into the madcap world of left-wing factionalism that is the fracturing of the Zengakuren.

So: to start with, we have probably the most bitter ideological dispute within the Zengakuren, between the Kakumaru-ha and Chukaku-ha. Both groups grew out of one of the early offshoots of the Japanese Communist Party–the Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyousanshugisha Doumei, or Japan Revolutionary Communists’ League.

When this group broke away from the JCP in 1957, it took with it its own revolutionary youth league, the Marugakudo, or Marxism Study Society. The Revolutionary Communists’ League then spent several years splitting and reforming before finally collapsing outright in 1963 over the issue of how to organize the revolution. One member of the League, Kuroda Kanichi, led a breakaway from the organization that became the Kakumaru-ha–the Revolutionary Faction of the Zengakuren.

The remainder of the league and its youth group then reorganized into the Chukaku-ha, or Central Core Faction. As you might imagine given their shared history, the Kakumaru-ha/Chukaku-ha rivalry was intense, to put it mildly. The two groups were among the most frequent Zengakuren factions to do battle with each other.

The Kakumaru-ha was also one of the most extreme factions among the Zengakuren–unlike many others, it had its own philosopher and thought leader in the form of Kuroda Kanichi, and Kuroda was fiercely opposed to any compromises in his political views, including alliances with other left-wing groups with the ‘wrong ideology.’ Kuroda was also much older than his student followers–36, at the time the Kakumaru-ha broke off–and his role as a ‘elder brother’/mentor figure for the group made him extremely influential among them.

You’ll notice I didn’t talk that much about the actual ideological differences between the two groups–broadly, Kakumaru-ha adherents supported a more traditional national mass party of the revolution (something closer to traditional Leninism), where the Chukaku-ha was in favor of a more decentralized revolutionary organization at the local or industry level. So basically this was purely a question of means, not even goals–but as I’ve seen, sometimes it’s the most minor disputes that produce the most bitter conflict.

By the late 1960s, both factions commanded between 5000-6000 foot soldiers and had several hundreds of millions of yen of cash at hand. The Chukaku-ha was more involved in many of the fights we’ve discussed over the last few weeks, like the attempts to stop PM Sato from going to South Vietnam or the campus occupations–it hoped to create chaos in the model of 1917 Russia to foment the revolution. The Kakumaru-ha, meanwhile, was more interested in organizing its national revolutionary party, though it was also plenty willing to fight the Chukaku-ha as needed.

So far, so good, but these are not the only ingredients in our chaotic pie. There’s also, of course, Minsei, short for Nihon Minshu Seinen Doumei, or the Democratic Youth League of Japan–an attempt by the Japanese Communist Party to re-assert itself among the nation’s students after it lost control of the Zengakuren by setting up its own youth movement. Minsei actually also still exists today, though its modern incarnation is not quite as violent as the 1960s one–in the late 1960s, Minsei was a participant in street battles against and alongside the Zengakuren factions.

Just to give you an idea of how maddening the factionalism gets, Minsei had its own breakaway group who felt the group was insufficiently zealous, called the Zenjiren–though we’re not really going to bother with them because otherwise the whole damn episode will just be talking about breakaway groups.

Meanwhile, the split of the Zengakuren in 1960 over the failure of the security treaty protests led the Japanese Socialist Party to set up its own youth group, the Nihon Shakaushugi Seinen Domei, or Japan Socialist Youth League–the hope being that the Shaseido, as it was known for short, would help the JSP pick up some of the pieces of the imploding Zengakuren.

Which worked….until the Shaseido itself blew up in a factional dispute in 1964. This time, the dispute was over the JSP’s own platform, which had begun to emphasize a gradualist policy of structural reform both to the party and to the country itself. More revolutionary members of Shaseido were angry at what they saw as a weak approach to revolution, and so broke away once again to form their own group–the Kaihou-ha, or Liberation Faction.

Then, finally, there’s the remainder of the old Bund which shattered after 1960. The original Bund broke into a series of competing factions such as the ML-ha (short for Marxist-Leninist Faction or Shagakudo–the Socialists Student League.

However, a small core of the Bund held on, particularly in the Kansai area centered on Osaka and Kyoto, and eventually organized a “Second Bund” in 1966 by merging with ideologically like-minded groups outside of the Kansai area.

In turn, the Second Bund would eventually form an alliance with the Kaiho-ha and the Chukaku-ha collectively called the “Three Faction Zengakuren”, or Sanpa Zengakuren.

Broadly speaking, then, we have three major factions–the Kakumaru-ha, the JCP’s Minsei youth league, and the Sanpa Zengakuren, of which the biggest member was the Chukaku-ha.

Confused? I don’t blame you. To quote William Andrews, “A diagram of the New Left groups in Japan in the 1960s is like the genealogical map of the most traumatized family in history, skewered by divorces and countless stepchildren.”

Seriously, there’s a lot more here. By my count, Stewart Dousey’s book on the Zengakuren lists no less than 20 different breakaway groups, and I’m not sure that’s all of them.

Ideologically, there wasn’t even that much daylight between all these different splinter groups. Generally, they fell into a pretty basic left-wing spectrum. On one end was a fairly small group of structural reformist students who rejected overt revolution in favor of participatory democracy and attempts to create socialism from within the system. On the other was a slightly larger but still marginal group of overt Maoists–extreme radicals who embraced Mao Zedong’s vision of perpetual revolution and extreme opposition to authority as well as more immediate confrontation with capitalist powers like the US (as opposed to a slower approach of waiting for those countries to collapse on their own). But the vast majority in the middle were some flavor of Trotskyite–still revolutionaries, but more moderate than the Maoists.

So why couldn’t these groups get along? It’s a hard question to answer, but I think there’s at least two distinct reasons. First, the very nature of the Zengakuren lent itself to this kind of factionalism. If you’ve ever read any Marxist theory, which of course you have because what else could possibly be a better way to spend your time, you’ve noticed that there is a lot of jargon. And that jargon does serve a purpose–there are a lot of very complicated ideas being bandied about, whatever you happen to think of the content of said ideas, and jargon serves as a useful shorthand for those in the know.

But the nature of Marxist jargon also has resulted in a long history of intense arguing about said terminology, because arguments over the jargon can serve as a sort of flashpoint for ideological conflict. William Andrews puts it somewhat poetically, “the very lexicon of Zengakuren and the student radicals was vibrant, but also faintly toxic, like a kind of overly concocted potion.”

But there’s also a simpler and far less abstract explanation for the violence between these groups. They’ve all, you may have noticed, got some history together, breaking apart and forming back together and breaking apart again. Totally independent of ideology, that history developed a weight all its own. To give one particularly notorious example, both the Chukaku-ha and Kakumaru-ha participated in the battles on the campus of Tokyo University that we talked about three weeks earlier, and both groups contributed to the final defense of Yasuda Hall against the police. But on the night of January 18, 1969, as the police were preparing to storm the campus, the Kakumaru-ha members on campus deserted their posts and fled.

Realistically, this was probably the right call; the Kakumaru-ha was smaller than the Chukaku-ha and could not afford ‘losses’ to arrests and prosecutions at the same level. Besides, the whole idea of trying to stop the police advance was obviously doomed from the start. But for the Chukaku-ha members on the campus, this was the ultimate form of betrayal–a cowardly abandonment of the struggle, akin to desertion by soldiers on the battlefield.

Thus, this moment joined a host of other “incidents”–slights and conflicts both real and imagined–that provided a rationale for fighting between the factions. They also made cooperation incredibly difficult; though the factions were occasionally able to set their differences aside for a common purpose, those alliances rarely lasted.

For example, one meeting called between Zengakuren splinter groups to discuss strategies for opposing the Vietnam war ended in chaos when the stage was stormed by Chukaku-ha members who hurled invectives at the Kakumaru-ha members present before physically attacking them.

As moments like this make clear, the relationship between Zengakuren factions was defined more than anything else by uchi-geba, one of the odd terms coined by the New Left during this time. It’s a combination of Japanese and German; uchi is Japanese for inner or within, both in the actual and metaphorical sense, while geba is short for gewalt, the German word for violence.

Thus, uchigeba is the word for infighting within the left, particularly among the factions of the Zengakuren. Thanks to this history of perceived betrayal and infighting, uchi-geba became the primary way in which these factions engaged with each other–and ultimately, more than anything else, became what destroyed the Zengakuren and the New Left in Japan in general.

And by the way, one other thing to clarify–uchigeba was not, in point of fact, confined to university students, nor was the Zengakuren (in all its tangled manifestations) itself.

Just like the US, a university education in Japan is four years long, meaning that by 1969 several years worth of Zengakuren activists had graduated from their universities (if they had not managed to shut their universities down for an academic year, at least). Thus, many of these factions had members who were no longer students but had moved into the labor force, particularly by the late 60s and early 70s. In particular, both Kakumaru-ha and Chukaku-ha had substantial presences in unionized labor; for example, the railway sector was divided between two unions on opposite ends of the conflict. One, the National Railway Chiba Motive Power Union (Kokutetsu chiba dōryokusha rōdōkumiai, or Doro-chiba for short) was affiliated with the Kakumaru-ha; it broke away from the National Railway Locomotive Engineers’ Union (Kokutetsu dōryokusha rōdōkumiai) because a Chukaku-ha member rose to the presidency of the group.

Indeed, by the 70s 80% of New Left activists were workers, not students, according to at least one estimate.

All of this is, I think, necessary context for understanding what comes next–the self-inflicted destruction of the New Left.

1968 and 1969 were the height of the New Left–the years of Zenkyoto campus occupations and the height of the anti-Vietnam war movement. Not unrelatedly, these were also years when many New Left activists ended up doing at least a little prison time. By 1970, many of them were getting out of prison–and by this time they were often hardened and embittered, which perhaps helps explain what came next.

On the morning of August 5, 1970, the body of a young man was found outside a hospital in Tokyo. He was quickly identified as Ebihara Toshio, a former student of Tokyo University of Education and a member of Kakumaru-ha.

Police investigation revealed that he’d been killed as part of escalating violence between the Kakumaru-ha and Chukaku-ha–for the past several weeks, the two groups had been skirmishing in Ikebukuro, where both had street presences and members who were trying to fundraise and distribute literature. Apparently, Ebihara had been a part of a Kakumaru-ha contingent which had attacked a Chukaku-ha fundraiser–in retaliation, he’d been kidnapped by Chukaku-ha members, taken to a nearby university campus (Housei University, specifically), and then beaten to death with metal pipes and wooden staves.

Ebihara’s death was a bit of a watershed moment. Up until this point, uchi-geba between the factions had been violent and dangerous, certainly, but never intentionally lethal. Indeed, only one student had died–a member of the Sekigunha, or Red Army Faction, who had been kidnapped by members of the Second Bund at Chuo University and fell out a window trying to escape his kidnappers.

To be clear, I am not excusing the violence up until this point because it was not lethal–but Ebihara’s death was still the first time members of one faction had INTENTIONALLY decided to kill someone in another.

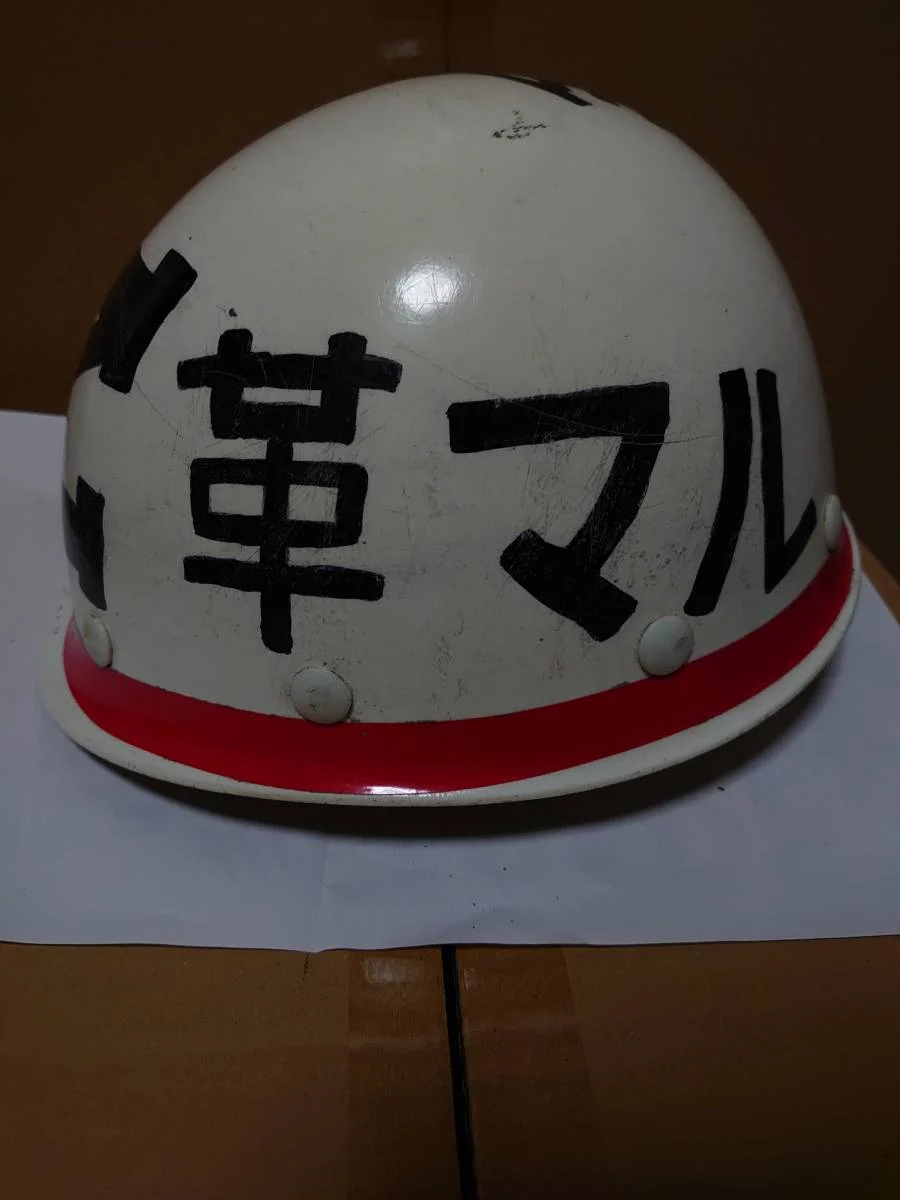

However, it would very much not be the last. A few days later, the Kakumaru-ha would retaliate with an attack on the Housei University–the factions distinguished themselves by differently colored helmets, and the Kakumaru-ha raid members used Chukaku-ha helmets to get in close before attacking. The result was a massive skirmish that had to be broken up by riot police.

These were the opening shots of what I can only really call a Kakumaru-Chukaku war–over the course of the next decade, there were over 1800 incidents of violence between the groups, and more than 60 members of the new left would be murdered.

Of these, the majority were members of the Kakumaru-ha–thanks to its smaller overall size and the fact that the Chukaku-ha was part of the Sanpa alliance (and could call on reinforcements from groups like the Kaiho-ha), Kakumaru-ha was largely on the defensive for much of the conflict, so to speak.

Now, I don’t want to go through these incidents of violence one by one because frankly, it gets fairly repetitive fairly quickly to do so. Broadly, most of the murders were assassinations, where members of one faction would attack or kidnap members of another and kill them. A comparatively small number were fatalities in factional street battles–the factions continued to martial members with sticks and helmets to fight in the streets of major cities (particularly Tokyo), but by the 1970s the police were fairly used to dealing with these.

For example, one battle in January, 1973 where Chukaku-ha members “invaded” a Kakumaru-ha bastion at Waseda University was very violent–but also broken up within 20 minutes by a squad of riot police (who also arrested 60 of the 700 Chukaku-ha members involved).

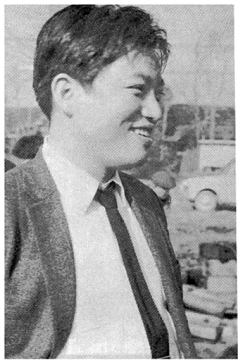

Most of the violence was smaller scale–members of each faction lived in fear of being ambushed at home, at work, or on public transit, and being kidnapped, dragged off, and killed. Leaders of both groups lived under pseudonyms in secret locations to avoid becoming targets, and even then it didn’t always work; on March 14, 1975, Honda Nobuyoshi–a senior leader of Chukaku-ha who had graduated from Waseda University in 1958–was ambushed by Kakumaru-ha members outside his apartment in Kawaguchi city in Saitama Prefecture. A neighbor called the police early in the morning, saying they’d heard crashing noises from the apartment and awoken to find shattered windows and overturned furniture. When the police arrived, they found Honda’s body inside.

Kakumaru-ha, by the way, was not shy about taking responsibility for the assassination, issuing a press release to the affect that: “Our revolutionary warriors from Zengakuren have dealt a crushing class blow, imbued with the fury of the proletariat, to the anti-revolutionary spy group Chūkaku-ha’s leader.” They then declared “ultimate victory” in the factional war and a unilateral ceasefire–but Chukaku-ha was not impressed; 14 Kakumaru-ha members were killed in retaliation assassinations over the course of 1975, which was also the bloodiest year of the whole conflict (19 murders in total).

The two factions would also occasionally raid each others headquarters (both publishing houses responsible for putting out the respective faction newspapers). The Chukaku-ha one is called Zenshinsha, and was located in Ikebukuro in the 1970s, while the Kakumaru-ha one was called Kaiho-sha, located in Shinjuku) These offices were often stocked with baseball bats and members responsible for defending the entrance should an attack happen. One journalist visiting the Kakumaru-ha headquarters in 1975 compared the experience to fears of going to Lebanon and being caught in the crossfire of its ongoing civil war.

Now, naturally enough you’re probably wondering: where are the police in all of this? After all, both these groups had headquarters which were registered businesses–it wasn’t like they were hiding what they were doing or where they were organizing?

The answer is that the police seem to have decided to let the two fight it out. During the 1970s, there were breakaway left-wing groups that actually did spend more time attacking the state than each other, and these groups were very actively targeted by law enforcement. But if the Kakumaru-ha and Chukaku-ha were going to put so much effort into killing each other? The prevailing attitude among the police seemed to have been to let them.

Incidents of overt violence, like that raid on Waseda University, were suppressed by the riot police. At the same time, the cops did investigate incidents of violence; ultimately 21 Chukaku-ha members were arrested in conjunction with the Ebihara murder, for example, and in 1974 alone the police arrested over 400 people in relation to incidents of uchi-geba and solved 54 cases (including five murders). The police also actively infiltrated both groups to gain intelligence on their members, leadership, and activities–though to be fair, neither was shy about publicizing their actions in their newspapers, so it wasn’t like they were trying that hard to hide what they were up to.

But certainly, it’s hard not to view the police response as a bit…disproportionately small, given the violence between the groups. Then again, the usual police response to radical groups was to try to decapitate their leadership with mass arrests, after which the group would dissipate: but Kakumaru-ha and Chukaku-ha were both too large for mass arrests to take out enough of the leadership at any one time.

You might wonder–what was motivating the members of these groups to fight like this? The answer, of course, was largely revenge. The death of Ebihara demanded a response from the Kakumaru-ha, lest the Chukaku-ha think it weak. That response demanded a response from the Chukaku-ha for the same reasons.

The cycle became self-perpetuating; as Honda Nobuyoshi remarked before his assassination, “War comes with war dead. Is it not natural that when two social groups fight a war using physical means there will be deaths? If you are fighting, it is meaningless to detach death for form’s sake.’

The whole thing is, naturally, reminiscent of Japan’s other famous source of turf wars: the yakuza. And the accusation that these factions were acting more like gangs than anything else was made constantly in the Japanese press.

But it is important not to forget that for those involved, the conflict did have an ideological component. For example, Chukaku-ha members were known to work themselves into a lather over accusations that the Kakumaru-ha was in league with the police and betraying the revolution (in fact the Kakumaru-ha was subject to more arrests because it was both larger and more commonly on the offensive.) They also accused the Kakumaru-ha of being fascistic–a group unable to tolerate differences in revolutionary strategy. These accusations served as a source of fervor, giving these acts of revenge an almost sacred meaning in terms of opening the path to revolution (and thus a better world). A Kakumaru-ha member, Domon Hajime, put the role of ideology succinctly: “You think we’re just killing each other, right? Like the goings on of the Yakuza? It’s not like that. Everyone thinks that this is utterly vital for the progress of their own revolutionary movement—they are wielding their iron pipes like they are praying.”

The war continued through the 70s and 80s, with each year producing more dead. It even expanded; Chukaku-ha’s alliance with the Kaiho-ha as a part of the Sanpa Zengakuren dragged that group into its own conflict with Kakumaru-ha. This too turned bloody and violent.

For example, in 1977, the Kaiho-ha leader Kasahara Masayoshi was ambushed on a train by Kakumaru-ha members and beaten to death with metal pipes. The Kaiho-ha, of course, did not let this go unanswered; a few months later, members of that group ambushed a van full of Kakumaru-ha members. They broke the doors of the vehicle so they would not open, then doused it with petrol and set it alight, killing all inside.

However, by the late 80s enthusiasm was clearly beginning to peter out. There were still incidents of violence every single year, particularly by Chukaku-ha members attacking members of the Kakumaru-ha affiliated part of the Japan Railways union (all part of a massive dispute around the privatization of the rail system, which Kakumaru-ha actually supported chiefly because more of JR’s employees were affiliated with a Chukaku-ha union).

By the 1990s, however, the pace of violence began to slow. Deaths still took place, and Kakumaru-ha even got wrapped up in a bizarre little side obsession: the group injected itself into the so-called “Boy A”/Sakakibara Seito murders (about which there is a bonus episode on this feed), believing the official verdict to be a police frameup and going so far as to break into police offices to find the ‘truth’.

Chukaku-ha, meanwhile, was very involved in an unrelated battle over the construction of Narita Airport (see episode 309), and was attempting attacks and sabotage against it well into the 1990s.

All of these groups still exist today, though many have shrunk substantially. Chukaku-ha is probably the largest still, though its protests pull in only a few hundred protestors instead of the tens of thousands they used to. Kakumaru-ha is also still around, as is Kaiho-ha–though that has since split into two competing factions engaged in their own competing uchi-geba.

The highest profile victim there was Katayama Mieko, a professor at Meiji University who was surrounded in the street and stabbed to death in 2000. The most recent incident of violent uchi-geba I could find actually relates to that very split; in 2004 one faction of Kaiho-ha attacked a hideout of another, resulting in several injuries from knife and hammer wounds (though no deaths that I could find).

Looking back at the history, it is frankly hard to avoid the conclusion that uchi-geba absolutely destroyed the Japanese New Left. Indeed, the math seems to bear that out; in 1972, records from the Ministry of Education suggested some 44,000 students involved to some degree or another in New Left groups, but by 1978 that number had plummeted to just under 13,000.

There’s obviously a lot of other things you can point to in terms of blame there. The growing economy, as we’ve talked about before, helped take the wind out of Japanese leftism in general. The end of the American war in Vietnam also brought an end to one of the most emotionally powerful appeals of the new left.

And in the wake of the 1968-1969 campus uprisings, legislation passed by the government of Prime Minister Sato Eisaku did badly handicap the ability of the various Zengakuren sects to organize on campus–it even allowed some universities to outright ban the jichikai student governments that had been the original vehicle of Zengakuren activism. Quite a few campuses flat out banned the groups altogether out a (not unjustifiable) fear of violence.

All of these are valid explanations for the fall of Japan’s new left–which is a shadow of its former self compared to the days when an individual faction could mobilize thousands of foot soldiers–independent of the bloody years of uchi-geba.

Yet it’s hard to escape the sense that uchi-geba, in the end, destroyed the New Left more than any other factor. As Andrew Williams put it, “the more byzantine the New Left in Japan became, the more its strength also dissipated. The strongest groups were engaged more and more with fighting each other (many many more members of protest groups have died through uchi-geba than in clashes with the state).”

Williams went on to reference a 1994 study of former new left activists regarding why they’d left political activism–the number one reason cited was the fear of uchi-geba. Violence didn’t just end up deterring members of other factions, but deterring people from being members of factions at all.

Why does this matter? Because, in a certain sense, it didn’t just hamstring the New Left. Remember, every single one of the groups involved in this little civil war–which, mind you, never officially ended, though what that would look like isn’t really clear–was an offshoot of one or another of a left political party. The Kaiho-ha was descended, so to speak, from the socialists; the Zengakuren and Marugakuha were breakaways from the Communist Party. And so the violence didn’t just reflect badly on the new left, but on the left in general.

I cannot prove this, but I strongly suspect that the violence and factionalism of New Left politics did a great deal to turn people off of the Japanese political left in general. Certainly, the timing tracks–the years of substantial decline for the Socialist party (once upon a time a serious political rival of the governing LDP) line up fairly well with the height of New left violence in the late 1960s into the 70s.

Put simply, I suspect a large number of Japanese voters began to believe that leftist politics in general was not a vehicle for improving their lives, and that in the absence of a serious alternative for the LDP they began to move in the direction of political apathy.

Certainly, the story of the Zengakuren and the implosion of the New Left is, if nothing else, an illustration of the importance of one of the most basic values of modern democratic politics: political pluralism. The factions of the Zengakuren could not, in the end, set aside their differences and work together for a common good. They couldn’t find it in themselves to collaborate where they did share similar views. And in the end, though they technically shamble on, in the political sense their obstinacy has cost them everything. A political force that once commanded respect is now a shadow of its former self.