This week: the dramatic career of Emperor Go-Daigo, who brought down the Kamakura shogunate and ended Hojo rule in Japan. This despite the fact that just a few months before victory, his forces were on the verge of defeat!

Sources

Hall, John Whitney, “The Muromachi Bakufu” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol III: Medieval Japan

Goble, Andrew Edmund. “Go-Daigo, Takauji, and the Muromachi Shogunate” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850

Images

Transcript

For my money, one of the most interesting recurring debates in history as a discipline, and one we’re going to return to quite a bit over the coming months, is the question of what drives the events of history themselves. Is history the result of complex, longterm and impersonal changes in social, economic, and political trends–in other words, is historical change driven by systems bigger than any one of us? Or is it driven by the actions of individuals, whose presence (or absence) at key moments determines how things will unfold?

The reality, of course, likely lies somewhere in the middle, but where precisely is the balance? That’s a hard question to answer, and I think the difficulties of it are illustrated nicely by the downfall of the Kamakura bakufu.

We’ve been covering, over the last few weeks, the growing systemic weaknesses of the government of the Hojo clan, set up in Kamakura on the eastern side of Honshu to maintain and reward the coalition of warrior families which had won the Genpei War.

Victory over the Mongol Invasions had been extremely costly economically, and the systems set up to reward Japan’s warriors for service did not operate very well when victory didn’t come with lands or plunder to redistribute. Similarly, the growing independence of the provinces made it harder and harder for the central government to capture and distribute revenue to its followers–meaning said followers increasingly saw less and less of an actual point to Hojo rule since they were not getting as much out of it.

Similarly, while the Hojo system was increasingly stable as the decades went on, it was ultimately a political structure based on personal alliances between the lead branch of the family and their supporters–alliances that could shift and collapse fairly quickly. For example, in 1285 the Adachi family, marital family and longtime supporters of the regent Hojo Tokiyori, was purged en masse–Tokiyori had died the previous year, and his son and heir was supported by rival families who wanted the Adachis cleared out to make room for their own influence.

This kind of thing is, to put it mildly, not great for producing stable or sane governance.

The Hojo government also had a hard time controlling the warrior class itself (ostensibly the whole point of the bakufu). Particularly in the provinces, banditry–or more accurately, renegade samurai who took what they wanted as “taxes” from local estates and who refused to allow legal verdicts to reign in their acquisitiveness–remained a serious issue.

The renegade jito–samurai charged with protecting the shoen estates, who in turn went around and extorted the estates without regard for the legal limits on their powers–were kind of iconic figures of the late Kamakura period, and that’s…frankly not a great look.

All of this meant that over time, various interest groups that had once supported the Kamakura government–provincial warriors, major samurai families from the Kanto area, and the like–became increasingly tepid on its future. And that, in turn, helps explain why when things finally came down to it, the whole thing collapsed like a house of cards.

Still–that explains why the Kamakura bakufu eventually fell apart, but not who started tearing it down and why. To answer those questions, we need to leave the realm of big systemic change and start looking at individuals and their presence in the historical record again, and to do that we need to return to an old stage for our story: Kyoto.

The imperial capital was not, to be clear, absent from politics during the age of the Kamakura government. The Kyoto court continued to operate much as it had for centuries before–indeed, we sometimes refer to this period in Japanese history as one of “dual government” for precisely that reason.

However, the civilian government of the Kyoto court did operate as a distinct subordinate of the military one at Kamakura during this time period–particularly after the abortive Jokyu Rebellion of 1221, when the retired Emperor Go-Toba tried and failed to claw back some power to Kyoto by force.

After his rebellion failed and Go-Toba was exiled, the Kamakura bakufu replaced him with a more pliant relative–Go-Saga, who first as emperor and then as retired emperor would dominate politics in Kyoto for decades until his death in 1272. While in power, Go-Saga’s tenure was generally defined by his support for the Hojo and the Kamakura government–naturally enough, given that they were the ones who put him in power in the first place.

However, after his death, things started to get messy–thanks to what else but a good old succession crisis entirely of Go-Saga’s making. As was the wont of aristocratic men of the time, Go-Saga had multiple female partners and thus a great many sons. As had been the case with many a retired emperor before him, he rotated these sons through the imperial seat as figureheads through whom he could run things–but showed a clear preference for his second son, Emperor Kameyama.

This naturally did not much please his eldest son, Emperor GoFukakusa (who was made to retire in favor of Kameyama and who did not much like being pushed into a secondary role despite being the older of the two).

Go-Saga’s death in turn created a succession dispute between supporters of Go-Fukakusa, who believed the imperial line should flow through him as the eldest son, and those of Kameyama, who believed that his father’s clear preference for him meant that his line should be the main branch of the family.

Now, all of this involves some EXTREMELY complex political wrangling that we do not have time to fully summarize here. Fortunately, if you’re interested, all you have to do is go back to episode 454–which is all about one of the women of the court during this time, Lady Nijo. Lady Nijo was intimately involved in the details of this moment–she was concubine to Go-Fukakusa and was exiled from Kyoto because of an affair she had with his hated half-brother Kameyama.

Her life is VERY fascinating in its own right and for the window it offers into Kyoto politics during this time, so again–check out episode 454 if you’re interested.

In the end, the Kamakura bakufu itself had to step in to head off more division in Kyoto–remember, all of this is happening in the middle of the Mongol invasions, so not exactly an ideal time for the Kyoto court to be turning on itself in this way.

The brokered solution arrived at in 1287 was a divided succession–Go-Fukakusa’s heirs would alternate on the throne with Kameyama’s, thus maintaining a balance between them (and between the various factions in Kyoto and Kamakura who saw some benefit in supporting one or the other).

And for a time, this balance worked. Go-Fukakusa was, by the traditional country, Japan’s 89th emperor. His younger half-brother Kameyama was number 90. For the next five imperial reigns, the succession would alternate effectively back and forth between the imperial lines–until we get to emperor number 96, known to history as Go-Daigo.

Go-Daigo was born under the name Prince Takaharu in 1288. He was from the Kameyama branch of the family (the younger brother), son of the 91st emperor Go-Uda and brother of the 94th Go-Nijo. His second cousin Hanazono (grandson of Go-Fukakusa) was elevated to the throne in 1308, and thus following the agreement created by the Kamakura shogunate Go-Daigo became crown prince. Ten years later, Hanazono would abdicate to focus on raising his nephew and children as future heirs, and because he was more interested in Rinzai sect Zen and the composition of waka poetry than politics. And so, Go-Daigo came to the throne.

By this time, the split between the two lines of the imperial family had gone from personal sibling rivalry to a question of high politics. You see, the division within the imperial line didn’t just affect the succession itself–each line maintained independent properties like shoen, for example, that it tried to pass down through relatives and political allies.

This could make for some VERY tense economic disputes; for example, in 1300 the two lines had a huge blowup when Muromachi-in, a Buddhist nun who was a daughter of one of the emperors from before this whole dispute started, died. This death was not terribly unexpected; she was 72, after all. But she had also inherited over 100 shoen from her family after her brother died unexpectedly.

Muromachi-in’s direct relatives were allied to the Gofukakusa side of the family (the opposite side from emperor Go-Daigo), but before she’d become a nun she’d married into the Kameyama side–and as a result, by the laws of the time, would pass the shoen on to her children after her death. This meant, in essence, that 100 shoen of wealth was about to swap sides in one go, completely upending the balance of power in Kyoto.

The Go-fukakusa side was naturally extremely upset at this prospect, and the tensions between all involved got to be such that the Kamakura government had to step in and mediate a solution (dividing the shoen 50/50 between the two branches).

The division wasn’t just economic, either–it was cultural. The Kameyama line, for example, became famous for patronizing new cultural developments out of China–for example, they brought over some of the first scholars of Neo-Confucianism, a Confucian revivalist movement that would come to dominate Chinese politics for the next millenium, and were big supporters of Zen Buddhism and Chinese-style arts like calligraphy.

Not to be outdone, the Go-fukakusa branch became major patrons of the older Japanese Buddhist sects like Tendai and of more traditional Japanese arts like waka poetry.

What I’m getting at is that by the time Go-Daigo inherited the throne Kyoto was a city deeply divided between these rival factions in a pretty profound way. Go-Daigo himself meanwhile was, from what we can tell, a man of profound ability.

For example, he made an effort to staff his court with men of ability, including those from the opposing Go-Fukakusa line. He was also interested in the details of policy; he was actually responsible for reforming the taxation rules in Kyoto itself, for the first time imposing taxes on artisans such as sake brewers rather than relying simply on taxation of the peasantry.

When a famine struck Kyoto in 1330, he intervened directly to pass edicts ordering price stabilization and the opening of government granaries to feed the population.

His name itself is actually something of a hint to his ambitions and talents. The prefix Go- in Go-Daigo indicates “latter”; Go-Daigo is also sometimes rendered in English as Daigo II. Emperor Daigo/Daigo I ruled back in the 900s; he was one of very few emperors early in the Heian period who was not dominated by Fujiwara clan regents, and who attempted with some success to re-centralize power under the imperial family (though his successors would not be successful in maintaining that legacy).

Go-Daigo was not known by that name during his own reign; until his death, he would have been referred to simply as the Emperor, and continued to use his personal name (Takaharu) when signing edicts. Similarly, the current emperor is referred to publicly as Naruhito; it’s only after he dies or abdicates that he’ll officially be styled Emperor Reiwa.

Go-Daigo was always open about his desire to emulate his illustrious ancestor Daigo in returning more power to the emperors, and his posthumous styling is almost certainly a tribute to his ambitions.

His hopes, however, were stymied from the jump. Around the time of his death the seniormost member of the opposing Go-Fukakusa side of the imperial family died, and there were serious worries that the balance of power between the two branches was about to tip again. Once more, the bakufu intervened to mediate a settlement to prevent a breakdown within the imperial capital.

As a part of that settlement, Go-Daigo’s position as the new emperor was re-affirmed–however, the bakufu also decreed that so as to prevent Go-Daigo from centralizing too much power within his side of the family, none of his children could ever inherit the imperial throne. Without that ability–raising his own heirs and preparing them to hang on to the power he intended to win–Go-Daigo was going to have a hell of a time actually succeeding in building a lasting legacy for the imperial court. Perhaps, like Daigo himself, he was doomed to spend his whole life working to strengthen the imperial line only to see his successors undo all that work without him there to ensure they didn’t.

And it was likely because of this very decree that Go-Daigo began to contemplate turning against the Kamakura bakufu. After all, if they were not around to enforce their decision, well, it wouldn’t matter at all then!

The moment to strike also seemed opportune. The last time an Emperor had tried to turn against the warriors of Kamakura more than a century ago, they’d been united by shared purpose and the leadership of Hojo Masako. Now she was nearly 100 years gone, and the Hojo were extremely divided–in 1311, the Hojo shikken, or regent, was replaced by a nine year old after the incumbent died, and that nine year old was…well, 9, and not a great leader–and at any rate resigned in 1326 because he hated politics.

After that, the Hojo spent the next four years trying to kill each other via a series of increasingly convoluted assassination plots I will not even bother you with in order to determine who was going to take over–not that it matters much, because it’s about to be irrelevant anyway.

At the same time, Hojo authority in the provinces was weakening. The bandit problem among the shoen estates was getting worse and worse, and in many cases local warriors supported those bandits–who, after all, were generally fellow samurai trying to sustain themselves off illegal taxes from local lands–than they did the decrees of the distant Hojo, trying to protect the property rights of shoen estate holders.

Decrees from Kamakura trying to bring the bandit problem under control–for example, 1324 one demanding that shoen owners hand over any captured rogue warriors or face having their lands confiscated–were routinely ignored. And it is REALLY not a good sign for your government when people start just flat out ignoring the things you say, especially (as was the case here) when you are unable to make them face any consequences for doing so.

Go-Daigo was not a fool, and he could see the faltering of the Kamakura government plainly. From what we can tell, as early as the first years of the 1320s he’d begun to plot against the bakufu and lay the groundwork for a rebellion. Unlike the Jokyu Rebellion of Emperor Go-Saga a century earlier, Go-Daigo was patient–for example, he carefully maneuvered two of his sons to the top of the Tendai sect temple of Enryakuji atop Mt. Hiei, bringing the influential clerics–and the wealthy temple lands, as well as a good sized army which defended them–around to his cause.

He also cultivated allies among the warrior class opposed to the Hojo, most notably in the Hino family, a group of Kyoto aristocrats who had switched vocations to become warriors over the past few centuries. Go-Daigo relied upon the Hino to reach out to their fellow warriors, especially those living outside of the traditional bastion of support for the Kamakura bakufu in the Kanto plains, and convince them to jump ship.

However, the Hino conspiracy to mobilize forces against the bakufu was successfully detected by agents of Kamakura’s Rokuhara Tandai–the agency responsible for monitoring goings on in Kyoto–not once but twice, in 1324 and again in 1331. The first time, Go-Daigo was able to argue he had nothing to do with these men raising an army in his name and got away unscathed. The second time this was…harder to do, and Go-Daigo ended up having to flee Kyoto a few days later for Nara, where he fortified himself atop Mt. Kasagi and called for all his loyalists to join him.

This…did not produce terribly inspiring results. The Kamakura bakufu promptly mobilized an army, scattered Go-Daigo’s defenders, captured the emperor, and forced him to abdicate. He was shipped off to the Oki islands in the Japan Sea, now a part of Shimane Prefecture–basically the middle of nowhere.

You’d think this would be it for Go-Daigo–his loyalists beaten, his armies scattered, he himself forced into distant exile. But, shockingly, it was not. And a lot of the credit for that has to go to one of Go-Daigo’s sons, known as Prince Morinaga.

Morinaga was one of the children Go-Daigo had worked to place into the leadership of Enryakuji, atop Mt. Hiei–hoping to bring the temple’s wealth and military might to bear for his cause. And from what I can tell, at least, Morinaga was not actually that interested in Tendai sect Buddhism; at least, it didn’t take up much of his time or energy. He was interested in helping his father succeed.

After Go-Daigo was exiled, Morinaga became the head the Kameyama branch (his side of the imperial line) while the Go-Fukakusa one was placed upon the throne by the bakufu. Morinaga carefully bided his time, quietly rallying more support among the warriors of central Japan–and crucially reaching out to the so-called akuto, or bandits, in the provinces.

Remember, many of these so-called bandits were just members of the warrior class who for one reason or another had gotten into it with the Kamakura bakufu (usually over property rights related to their shoen). They were perfectly good fighters–indeed, well practiced ones–and useful people to have on your side.

For a good while, Morinaga was patient, but by the 11th lunar month of 1332 (so around 1 ½ years into his father’s exile) he had left Enryakuji and was openly rallying followers in the Yoshino area of Yamato province about 100 KM/61 miles south of Kyoto.

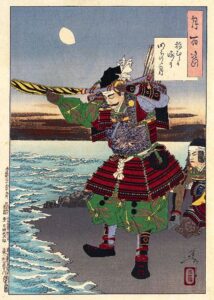

As news of this got out, he was joined by one of the followers of his father’s original uprising, and someone we do simply have to talk about: Kusunoki Masashige.

Now, Kusunoki Masashige is one of those figures whose story is so much wrapped up in legend and myth that it’s hard to separate historical fact from later fiction–for reasons we will get to more in the next episode.

Indeed, very little is known of Kusunoki before this time. The Taiheiki, the dramatized history of the conflicts we are about to discuss, describes him as being descended from Tachibana no Moroe, a major figure of Nara-era politics (he was a backer of Empress Kouken, who we talked about back in episode 505) and a distant relative of the Minamoto clan. None of this is backed by any other source, however, and one thing we’ll see is that sources from premodern Japan have a tendency to invent illustrious backgrounds for famous people from whole cloth.

All we know for certain is that Kusunoki Masashige–born in 1294–was a minor landholder in Kawachi Province (what’s now Osaka prefecture) who answered Go-Daigo’s original call to rise up in 1331 with a few hundred men under his command.

After Go-Daigo was defeated and exiled, Kusunoki Masashige did NOT do what most of his compatriots did–accept defeat and hang it up. Instead, he kept fighting, leading a guerilla campaign against the Kamakura shogunate for the next year and a half while constantly harassing their military forces as best he could.

And when he got word of Prince Morinaga’s second uprising, well, naturally enough he joined that too.

And here, the tides of fortune began to shift dramatically against the Kamakura bakufu. Prince Morinaga, knowing a seasoned commander when he saw one, naturally placed Masashige in command of a good chunk of his forces. Masashige then advanced and, in the first lunar month of 1333, defeated an army sent by Kamakura to stop him in the vicinity of Shitennoji in what’s now Osaka.

The bakufu counterattack was not long in coming, and drove Masashige out of the fortified Akasaka castle in the foothills of Osaka. However, he was able to escape with most of his forces intact and retreat back to Chihaya castle further up the mountains–and when the bakufu forces followed him there, they were greeted with the classic tactics of the akuto bandits.

Kusunoki Masashige relied on ambushes and raids on the bakufu besiegers, as well as tricks like the use of straw dummies to hide weaknesses in his defenses–bleeding the bakufu besiegers and trapping them in the valley leading up to Chihaya itself.

From here, things snowballed. Rebellions against the bakufu by anti-Hojo warriors crapped up in Harima, and Iyo provinces (modern Hyogo and Ehime Prefectures) by the end of the first month. Go-Daigo, getting wind of what was going on, slipped his captors on the Oki islands and raised a new army to return to Kyoto.

At this point, the Kamakura bakufu–finally realizing how bad things were going–mobilized two armies in the eastern Kanto to send to Kyoto and crush the rebellion. One of these was led by a guy named Nagaoshi Takaie, and I will not bother you with him further because he’ll promptly stumble into a trap set by one of Go-Daigo’s loyalists, Akamatsu Norimura, and get himself and all his followers killed.

The other was led by a guy who we REALLY need to talk about, whose name was Ashikaga Takauji.

Now, I think it is fair to call Takauji absolutely the most controversial figure from this entire period–once again, one of those guys who makes separating myth from legend a bit of a challenge. Fortunately, that complexity has more to do with his internal motivations (especially around his later actions) than it does with his origins.

The Ashikaga were a pretty prominent family already by this time. They were distantly related to the Seiwa line of the Minamoto family–they traced their lineage back to one Minamoto no Yoshiyasu, grandson of the famous Yoshiie and distant cousin to Yoritomo. Yoshiyasu had thus fought for the Minamoto in the Hogen and Heiji Rebellions and survived to fight in the Genpei War on the Minamoto side as well. For his troubles, Yoshiyasu and his son Yoshikane (who joined him on the battlefield for the Genpei War) were rewarded with jito manager rights over a shoen estate in Shimotsuke province (today Tochigi prefecture north of Tokyo), named Ashikaga-no-sho–and so eventually began to call himself Ashikaga Yoshiyasu to distinguish himself from the other Minamoto.

Yoshiyasu’s son Yoshikane also married into the Hojo family, and after Yoritomo’s death in 1199 and the 2 and a half decade mess that followed it the Ashikaga naturally shifted allegiances over to the Hojo. Indeed, the name “Ashikaga”–derived from the shoen in which the family had first settled–appears pretty prominently in the list of pro-Hojo forces from accounts of conflicts throughout the Kamakura bakufu’s history.

This history made Ashikaga Takauji a pretty natural choice as a commander of a pro-Hojo army sent to deal with Go-Daigo once and for all. Except that’s not quite what happened.

You see Takauji took his armies and marched west from the Kanto in spring of 1333; by this point, Kyoto was already the site of battles between pro- and anti-Hojo forces, and Takauji’s armies would tip the scales decisively–particularly because he made his way first to Tamba province north of Kyoto, home to many followers of his mother’s family the Uesugi, to bolster his forces further.

However, then the unexpected happened–Takauji switched sides.

When exactly Takauji made the determination to swap sides is unclear (though we do know he was in contact with Go-Daigo’s forces for a while before he officially flipped over to the emperor’s cause) –as is why.

One of the tricky things about this period–and indeed much of Japanese history before the last century and a half or so–is that the major leaders did not keep diaries, or if they did those diaries were kept secret and never made publicly available. This contrasts quite a bit with, say, big chunks of European history–where you have things like family letters or diaries that are far more explicit about the internal lives of the participants in major events.

So we’re left with a lot of speculating as to the motives of major historical figures. In the case of Ashikaga Takauji, it’s often suggested that he turned on the Hojo at least in part out of a sense that he’d been slighted by the Kamakura bakufu–that the shogunate had not sufficiently honored him, and thus he’d decided to betray it. This is the version given by the Taiheiki, where Takauji responds angrily to an order to both fight for Kamakura and take a special renewed oath of loyalty before he marches off to battle: “[the shikken Hojo] Takatoki is but a descendant of Hojo Tokimasa, whose clan long ago came down among the commoners, while I am of the generation of the house of [Minamoto], which left the imperial family not long since. Surely it is meant that Takatoki should be my vassal instead of contemptuously handing down orders such as these!”

Another theory involves the Ashikaga shoen from which the family took its name. Remember, the Ashikaga were the jito of that estate, responsible for managing its security and relations with the warrior population. But who was the actual estate owner? Well, the Ashikaga shoen actually belonged to the imperial family–specifically, to the Kameyama branch from which Go-Daigo descended. So perhaps Ashikaga Takauji saw himself as owing his loyalty to the imperial line and Go-Daigo.

It’s also sometimes suggested that Takauji simply saw the bakufu for what it had become–weak, riven with factionalism, and unable to functionally control the country. And thus, he decided that preserving it was not worthwhile, and moreover that a new government would serve the country better.

And this is a very interesting question to consider, because the debate on what motivated Ashikaga Takauji is very important for discussions of his character and historical reputation. I don’t think there is a clear or obvious answer here, to be honest, but for my money there is one answer to the question of his motives that tends to stand out–and I do want to be clear here that I’m relaying my opinion here, and that opinion is grounded more in a broad sense of Takauji than anything else. Take it for whatever that’s worth to you.

You see, I am a believer in the idea that you can get some sense of a person’s character from their actions–that, in essence, someone is what they do. And I do get a sense, I think, of at least a part of Takauji’s character purely from his actions over the next few years. The main thing that jumps out to me personally, frankly, is that Takauji was a pragmatist. He was, in my view, motivated simply by a political instinct to do whatever advanced his own interest, without a lot of concern for the long-term consequences.

I think you can see this a bit more clearly when we talk more about him next week.

Read through this lens, Takauji’s betrayal of the Hojo is simple enough to explain. He saw an opportunity to advance his own interests, and he took it. But again, that’s just my read on things.

Regardless, with Takauji on his side Go-Daigo’s forces swiftly took Kyoto early in the fifth lunar month of 1333. The Hojo loyalists stationed in the city fled with the emperor installed to replace Go-Daigo (known to history as Emperor Kogon) but did not make it long before they were captured, with the Hojo warriors escorting the emperor either dying fighting or committing suicide to avoid capture.

The day before Kogon was captured, Hojo rule in Kamakura collapsed. The culprit was one more betrayal. Nitta Yoshisada, a warrior who had previously fought for the Hojo (he’d actually fought Kusunoki Masashige at the Battle of Chihaya Castle) had later decided to swap sides. His motives, again, are unclear; the Taiheiki says that he was treated poorly by a taxation official sent to his personal shoen, but other sources suggest that he was convinced to swap sides by Go-Daigo’s son Prince Morinaga, who was by all accounts a charismatic leader in his own right.

Regardless, Nitta Yoshisada raised an army from his home in Kozuke province in the interior of Honshu and marched on Kamakura. Despite being outnumbered initially by Hojo defenders of the city, he was able to defeat Hojo armies several times–thanks largely to either defections to his cause by warriors who could see which way the wind was blowing, or by local samurai and “bandits” who joined him out of hatred of the Hojo.

And again, precisely one day before Emperor Kogon and his followers were captured retreating towards Kamakura, Nitta Yoshisada’s forces broke through the final defenses of Kamakura. They annihilated the remaining defenders and torched a good chunk of the city; Hojo family members and loyalists generally died fighting or committed suicide.

Hojo rule, and the Kamakura bakufu, were over. Within the week, Go-Daigo would issue an edict–still on his way to Kyoto–removing Emperor Kogon as emperor and returning himself to the throne, and vacating the two positions of shogun and shikken.

He had, it appeared, succeeded–power had been restored to the emperor and the throne.

We call this period the Kenmu Restoration–it was, after all, an era of restored imperial political power, and Go-Daigo changed the nengo upon taking the throne to Kenmu–a phrase that’s rather hard to translate. Ken is the character for “build” or “construct”; mu is “arms”, “warriors”, or more poetically “chivalry.”

So, something like “raising the martial spirit”, I suppose–a recognition on Go-Daigo’s part of what had enabled his rise to power.

Because while Go-Daigo’s rule on the one hand represented a return to an older arrangement of power with the imperial family at the center, on the other it wasn’t much of a change at all–after all, it was the warrior families who backed him that enabled his victory over the Hojo.

Most central to his new regime were three warriors in particular. Kusunoki Masashige, that early loyalist who had stuck by Go-Daigo’s cause even in its darkest moments, was naturally one of them. Ashikaga Takauji, whose betrayal of the Hojo had turned the tide in Kyoto, was another. Then there was Nitta Yoshisada, who had finished off the Hojo family for good.

With their support, Go-Daigo set about establishing a new government and rewarding his followers. For example, Takauji received a court rank (junior fourth grade), the privilege of using one of the characters from Go-Daigo’s own personal name (the taka in Takaharu is also the Taka in Takauji), as well as the governorship of two provinces and shugo rights over another and a whole truckload of landholdings.

Surely, we are now on the cusp of a new age of political stability under this revived Kyoto government!

And I’m checking my notes here and…next week it all comes crashing down into a massive civil war. Oof, that sounds bad.