This week: why did the Mongols invade Japan? How did a seemingly invincible military machine falter in its assaults on the island of Kyushu? And why, in the long term, did the Mongol invasions begin the process of bringing down the Kamakura shogunate?

Sources

Conlan, Thomas D. In Little Need of Divine Intervention: Takezaki Suenaga’s Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan

Ishii, Susumu. “The Decline of the Kamakura Bakufu.” Trans. Jeffrey P. Mass and Hitomi Tonomura in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol III: Medieval Japan

Images

Transcript

Some time during the period of samurai political emergence–the date is disputed, but 1162 is the most commonly favored year–a boy was born thousands of miles from Japan.

The precise date and location are a matter of some dispute–again, 1162 is the most commonly favored choice, but the source from which that was derived was decades removed from the fact. In terms of location, the most commonly cited is the banks of the Onon river in what’s now Khentii province in northern Mongolia.

Indeed, much of the young life of this boy–which took place as the rule of Taira no Kiyomori was coming together–is the subject of mystery or legend (or both). He would not emerge into contemporary written sources until decades later, and by the time he was famous enough for there to be an interest in his young life, well, so many stories had accumulated around him that it was near impossible to sort truth from legend.

It’s clear that the young boy named Temujin was a talented warrior. His station was comparatively humble; his father Yesugei was a chieftain, but not a particularly wealthy or powerful one.

And at any rate, the steppe nomad group to which young Temujin belonged–the Mongols–were not the strongest or fiercest or most powerful group on the wide open steppelands of Eurasia. At least, not yet.

Of course, that name–Mongols–both gives away who we’re talking about and where all this is going. Because while I would wager most people have not heard of Temujin or Yesugei, they have heard the name Temujin would eventually take after leading his followers to glory and power: Genghis Khan.

And by the way, I am reliably informed the actual Mongolian pronunciation is closer to Chingghis Chan”, but I’m going to stick to Genghis Khan simply for reasons of recognizability. I hope any Mongolian speakers in the audience can forgive me.

A full recapping of the origins and expansion of the Mongol empire is a bit beyond the scope of podcast–indeed, it’d be a podcast all its own. Suffice it to say that over the course of one of the most legendary political and military careers in human history, Genghis Khan took the Mongols from a minor player in the politics of the Eurasian steppe to masters of an empire that sprawled over a good chunk of China all the way to the edges of Europe.

To do it, he killed untold numbers of people–literally, it’s very hard to estimate how many people died in the rise of this empire, but even the most conservative estimates would make the rise of Genghis Khan one of the most destructive events in the history of humanity.

Japan, however, remained untouched by the initial wave of conquest, for that most basic of reasons–geography. The strength of the Mongol empire lay in its land-based logistics and ground tactics, and those things become a bit trickier to use when you’re talking about a group of islands over 100 miles off the shore of the mainland.

Specifically, if you’re wondering, the shortest crossing is from Busan in Korea to more or less Fukuoka in Kyushu–and that’s 135 miles, or 218 kilometers. So not exactly a luxurious day out boating.

Of course, the leadership of the Kamakura shogunate was well aware of what was happening on the continent. The shogunate was emerging in the early 1200s, right around the time Genghis Khan was conquering China (for example, he took what’s now Beijing in 1215). Through merchants going to China, as well as Buddhist monks engaged in pilgrimages, the Kamakura leadership received regular updates on the progress of the Mongol advance.

A good number of Chinese refugees actually came to Japan to escape the Mongols as well–after all, with all that water between them, clearly they were safe?

Except, of course, that this did not last. Genghis himself seems never to have contemplated an invasion of Japan–nor did his successors Ogedei, Guyuk, and Mongke (respectively, Genghis Khan’s eldest son, grandson by Ogedei, and grandson by another child). It was not until the fourth Khan, Kubiliai, that an invasion was considered.

By this time, the Mongol empire was far less unified than it had been; its sheer size had led to a growing fragmentation between competing descendants of Genghis Khan, each of which claimed a different chunk of what had become the largest empire in the world. Kubilai, nominally the khagan–the ruler of the whole empire–in practice found his influence largely limited to its single wealthiest segment.

This was China, which was still in the process of being conquered–it was not until well into Kubilai’s reign and after the first Mongol invasion of Japan that the final holdouts of the previous Chinese dynasty, the Song, were defeated.

Still, even this smaller empire represented a tremendous amount of wealth and manpower–certainly enough to threaten Japan, particularly given the decentralized and fragmented nature of its government.

By the mid-1260s, Japan was already on Kubilai’s radar, thanks both to its proximity–neighboring Korea, ruled at this point by the Goreyo dynasty, had already been subjugated–and because it had been a trading partner of the Southern Song dynasty, as that final remnant of pre-Mongol rule had been known.

In 1266 Kubilai sent his first letter to Japan, by way of the Korean kings of Goryeo who were ordered to act as intermediaries and accompany his messenger. However, that messenger was turned away upon arrival in Japan–it was not until 1268 that a letter from an at this point incensed Kubilai (who had made it clear in no uncertain terms to the Koreans that they were to convince the Japanese leadership to read what he had wrote) made its way to Kamakura.

That letter reads: “From time immemorial, rulers of small states have sought to maintain friendly relations with one another. We, the Great Mongolian Empire, have received the Mandate of Heaven and have become the master of the universe. Therefore, innumerable states in far-off lands have longed to form ties with us. As soon as I ascended the throne, I ceased fighting with Koryo and restored their land and people. In gratitude, both the ruler and the people of Koryo came to us to become our subjects; their joy resembles that of children with their father. Japan is located near Koryo and since its founding has on several occasions sent envoys to the Middle Kingdom. However, this has not happened since the beginning of my reign. This must be because you are not fully informed. Therefore, I hereby send you a special envoy to inform you of our desire. From now on, let us enter into friendly relations with each other. Nobody would wish to resort to arms.”

Now, that is about as unsubtle as it gets in the wild world of politics–certainly the language was peaceful, but the implications were anything but. And to make matters worse, leadership within the Hojo family had just transitioned, with a young boy of 17, Hojo Tokimune, having risen to the post of shikken–regent to the shogun.

Tokimune was young and untested, but he had a good pedigree going for him; his father was Hojo Tokiyori, the fifth shikken, whose rule is generally considered to be a golden age for the Kamakura shogunate–a period of substantial economic prosperity thanks to growing trade with China, as well as the invention of new agricultural techniques to clear arrable lands and use them more efficiently (such as double cropping).

Tokiyori had retired from office in 1256 and died in 1263, but his influence was such that the shikken since and a good chunk of his son Tokimune’s inner circle were still very attached to his memory–a fact which would serve his son in good stead.

So, how did this group of leaders handle Kublai’s missive? Well, the emissaries delivering it were not given a response and instead ordered home. We also have fragmentary evidence suggesting messages were sent to western Japan to order local samurai to prepare defenses for a potential invasion (though only one of the messages, to the shugo of Sanuki Province in Shikoku, now Kagawa Prefecture).

It was clear the Kamakura government was not going to accept Kublai’s demands, and as early as 1268 he had ordered the king of Korea to begin assembling an invasion fleet and drafting men to fight. He did continue diplomatic overtures as well–another messenger made it to Tsushima, the Japanese held island in the middle of the strait between Korea and Japan, before being confronted by the locals.

Apparently, a skirmish ensued that saw the Mongol envoy head back to the continent with two Japanese prisoners–who were interviewed by Kublai before being returned home with yet another letter professing his peaceful intentions.

Still, even as the great Khan continued to insist on his desire for peace, he had begun preparations for war–albeit somewhat delayed by a rebellion in Korea against the Goryeo monarchy, driven at least in part by said monarch’s collaboration with the Mongols. That rebellion took until 1271 to crush, delaying any plans for an attack.

In the end, an invasion would not come until 1274, after several more attempts by Kublai to force submission diplomatically (all rejected without answer) and after the completion of several more military campaigns.

In particular, Kublai delayed the invasion to finish securing his control over Korea, and to complete his attack on Xiangyang, the fortified city in southern China that was halting his advance into the south of the country. That fortress, besieged since the mid-1260s, finally fell in 1273, freeing up money and troops for an invasion of Japan.

Kublai initially planned to dispatch his forces in the 7th lunar month of 1274. However, delays–particularly around the construction of the more than 900 ships required for the attack–pushed the start back to the 10th lunar month, and even then many of the warships in the Mongol fleet (mostly built in Korea) were of rather haphazard workmanship to meet the Khan’s extremely demanding timetable.

Still, the sheer scope of the invasion was by all accounts incredible–the histories of China’s Yuan dynasty (as the period of Mongol rule came to be known) described 15,000 Yuan dynasty soldiers, a further 8,000 Koreans, and an astonishing 67,000 boat workers and other maintenance people.

How reliable those numbers are is a matter of contention, but it is clear the force involved was substantial.

The first wave of the invasion arrived on Tsushima on the 5th day of the 10th lunar month of 1274–November 4, by the Western count. The shugo, So Sukekuni, led a valiant defense with the 100 men at his command, but they did not stand much of a chance at all.

Nine days later, the nearby Iki island just off the coast of Kyushu was similarly captured, and two weeks after that, the Mongol forces arrived in Hakata bay in Kyushu.

Now, it’s worth taking a moment here to quickly stop and talk about the political arrangement of power in Kyushu, because that will matter to us quite a bit here.

That island was, by the standards of the mid-1200s, rather remote from Kamakura, which made it challenging to control–even more so because of its geography, which as we’ve already described divided the island into roughly three bands running east west with substantial mountain ranges between them.

To maintain his hold on such a remote island, way back in 1185 Minamoto no Yoritomo had set up an office he called the Chinzei Bugyo, roughly “Magistrate for the Defense of the West,” who would be deputized, in essence, to serve as the voice of the shogunate in the region and to manage things locally–avoiding the need to constantly run questions or policies back to distant Kamakura.

The Chinzei Bugyo was set up in Dazaifu, now a part of modern Fukuoka City along Hakata bay in Northern Kyushu–this being the region that was easiest to reach by boat from the heartland of Japan in the Kansai area, it was also the most developed and heavily settled region of the island.

Holders of the post were chosen from the region’s shugo, or military governors of the provinces of Kyushu, and charged with coordinating the shugo in support of bakufu policy–and with keeping an eye on them to ensure they were toeing the lines set by Kamakura.

In 1274, the position was held by two men splitting its duties in advance of the invasion: Shoni Sukeyoshi, who had been appointed in 1268, and Otomo Yoriyasu, sent down in 1272 to assist him. Both were also shugo in their own right, responsible for rallying their local colleagues to defend Hakata–the obvious spot for an invasion, given its central position and the fact that a force landing anywhere else would have to march over at least one mountain chain to attack the bakufu nerve center in the West.

They were in command of a force of unclear size, because the nature of the Kamakura bakufu’s organization makes it hard to estimate. Essentially, shugo in specific provinces would be given an order to mobilize their forces. They were responsible for rallying local samurai living in the province–both the jito and gokenin, a term that’s hard to define specifically without a long-winded tangent, but which broadly refers to lower-ranking samurai loyal to the shogunate. Those jito and gokenin who had their own followers would in turn mobilize them, and so on down the chain.

In other words, it’s not like there was a clean tally of “X number of potential fighters living in Y province” that makes it easy to tally up how many fighters there were on the Japanese side in 1274. Almost certainly their numbers were less than the Mongols–beyond that, it’s tricky to say.

This first battle–the Battle of Bun’ei, as it’s often known, since it took place in the 11th year of the Bun’ei era–was not what you’d call a decisive win for the Japanese side. Hakata fell extremely quickly, and Japanese forces skirmishing with the Mongol troops met with inconclusive results.

The Mongol forces were well-coordinated and trained to work together–where differing bands of samurai brought together to fight may never have met before–and had access to explosive gunpowder weapons brought over from China. On the other hand, the Japanese forces knew the terrain much better than their attackers, and were able to harry the Mongol forces. However, attempts to counterattack–for example, a strike on Mongol landing sites at Torikai Beach west of Hakata–ended in defeat, and one of the major local shrines (Hakozaki Hachiman Shrine) was burned by the Mongols. Not exactly an impressive outcome, and certainly not the sort of thing that would make the Gods look favorably on your endeavors when you would presumably need them most.

Eventually, the Mongol forces withdrew to their boats–not an acknowledgement of defeat, mind you, but a tactical retreat and reorganization to prepare for a second attack. And then, of course, came the storm.

In the course of a single night, a typhoon blew through and destroyed huge chunks of the fleet–forcing the Mongol commanders into a retreat back to the continent.

This first invasion had been warded away–but, as the phrase “first invasion” somewhat gives away, this was not the end of it. Kublai would, once his forces came limping home, dispatch one more embassy to Japan to try and force peaceful submission–after all, his armies had lost, but they weren’t wiped out.

That embassy arrived in Dazaifu in summer, 1275, and were forwarded on to Kamakura. And this time, there was a clear Japanese response.

An emboldened Kamakura leadership, led by the young Shikken Hojo Tokimune, ordered all the envoys rounded up and publicly beheaded.

This pretty much guaranteed another invasion all its own–after all, it was an act of deep disrespect to Kublai to kill his emissaries like that. But the response would not be immediate; Kublai and his advisors decided to prioritize a more immediate issue, and finish off the remnants of the Southern Song dynasty.

In 1279, the final bastions of the Song fell to Mongol/Yuan dynasty forces–freeing up even more soldiers, and capturing the substantial Song dynasty navy which could serve as a platform for the invasion. Kublai also ordered his new Chinese and Korean subjects to continue expanding his invasion fleets, and even established a government Ministry for the Conquest of Japan composed of his own veteran commanders and captured Song dynasty generals, tasked with drafting battle plans.

The Kamakura leadership had not been idle in the meanwhile; almost as soon as the first invasion force was dispatched, Hojo Tokimune and his advisors (most notably his father in law Adachi Yasumori) began busily planning for the next one.

Local shugo were ordered to contribute to shoring up the defenses of Hakata, including stone fortifications around the bay–extremely unusual for the period, as the cavalry-heavy armies of the period tended to rely on maneuverability and light fortifications of rammed earth and wood rather than stone defenses.

And these were no minor fortifications. They only remain partially intact today, but from records and remains we can deduce that they were huge–1.5 to 2.8 meters high depending on the place (that’s between 4.5-9 feet). And it was long–20 kilometers side to side across Hakata Bay, so about 12.5 miles. And to boot, the whole thing came together in just over a year starting in 1276, thanks to an edict drafting local shugo and gokenin as well as all the shoen holders of Kyushu to support it financially. For example, a document from Osumi province suggests that shoen holders were responsible for funding one shaku of the wall (a bit less than a foot, or 1/3rd of a meter) for each cho of arable land in their shoen (slightly less than one hectare, or 2.4 acres).

The power of local shugo was also substantially expanded–they were given the ability to “tax” even non-samurai in their territory in support of defensive efforts. For example, the shugo of Aki province in Western Honshu seized a fleet of ships and a large shipment of rice bound for the owner of a shoen in Kyoto as a “tax” to support the defense efforts.

Somewhat more cynically, the Kamakura leadership took advantage of the opportunity presented by the war crisis to strengthen their own political power. Of the 11 shugo appointed to their positions between 1274 and 1281, 8 were members of the wider Hojo clan family. The other three were from the Adachi, the in-laws of Hojo Tokimune.

Simply put, Tokimune was, in the time-honored tradition of leaders everywhere, taking advantage of a political crisis to centralize more power under himself and his closest allies.

Jito, gokenin, and other samurai who had holdings in the Western part of the country were also ordered to head out to the region and take up full-time residence there.

Previously, a given warrior could have land-holdings or rites in the provinces but appoint someone else to manage them–Tokimune ordered anyone benefitting from rights in the western part of the country to reside there, a measure intended to relocate large numbers of warriors to an area where they would be shortly needed.

Finally, and perhaps most audaciously, plans were even briefly drawn up for a potential retaliatory invasion of Goryeo-dynasty Korea in order to take away the springboard for another invasion; we have orders from late 1275 to the shugo of Western Japan to begin assembling their men as well as fleets for an attack. That attack never actually materialized, of course, probably because before long cooler heads prevailed. Why go on the attack, after all, and give up the massive advantage of forcing the Mongols to attack into prepared defenses across a wide open sea?

Still, the fact that this was considered is remarkable–and shows how much the war was at the fore of the minds of leadership during these years.

Back on the mainland, Kublai Khan gave the order for his second invasion force to be dispatched in the first lunar month of 1281–though a final set of logistical delays pushed back the start of the invasion to the fifth lunar month. Once again, estimating the numbers behind the Mongol force is challenging, but it’s clear this invasion was larger than the original–the history of the Yuan dynasty suggests 3500 ships, a mixture of Yuan dynasty and Goryeo Korean crews, in the invasion fleet.

The Kamakura leadership seems to have been aware another invasion was coming–they even had the timing more or less down, as a letter from the Kamakura leadership to one of the shugo of Kyushu suggested the 4th lunar month of 1281 as the likely arrival time for another attack.

Once again, the invasion met stiff resistance. Iki and Tsushima, which had been determined to be indefensible, swiftly fell to the Mongol forces. But here, the Mongols immediately ran into problems. Their forces were divided into two distinct staging groups–the Jiangnan Division, a mostly Yuan dynasty invasion force, and the Eastern Route Army, composed of about 25% Korean soldiers with the rest a mix of different Mongol fighters. The goal had been for the Eastern Route Army, which was the first to depart, to take Iki island and then await the arrival of the Jiangnan Division (planned for the fifteenth day of the sixth lunar month), so that they could advance onward to Hakata together.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, the Eastern Route Army did not wait. Instead, it advanced on to Hakata early in the sixth lunar month without the Jiangnan Division reinforcements. Upon arriving, the commanders of the Eastern Route Army forces discovered the newly constructed stone walls of Hakata–rather than attempting a landing and attacking those walls, a daunting proposition to say the least, they settled on occupying Shiga island off the coast of Hakata.

The Japanese commanders on the ground, led by the same Otomo Yoriyasu who had fended off the first invasion, wasted no time in mounting a counterattack and assaulting the island–though they didn’t crush the Mongol forces, the Eastern Route Army did withdraw as a result.

But hey, soon the Mongols would get reinforcements, right? Except, not so much. The Jiangnan army did not even leave the coast of China for Japan until the middle of the sixth lunar month (by which time they were supposed to be rendezvousing already with their Eastern Route counterparts). The culprit? The sudden illness, and eventual death, of the Chinese general placed in command of the force.

The two prongs of the Mongol invasion did eventually manage to link up early in the 7th lunar month–not at Iki island but in Hirado bay on the western side of Kyushu. From there, they proceeded to Takashima bay about 93 km (or 58 miles) to the west of Dazaifu and Hakata Bay–planning, presumably, to land there and then march to Hakata overland to avoid the fortified defenses of Hakata bay itself.

Otomo Yoriyasu and the rest of the Hakata defenders had, of course, gotten wind of the Mongol position from the locals, and had moved their forces to intercept. All was in place for a climactic final battle. And then, once again, the storms.

For the second time, a massive typhoon swept through the Mongolian fleet overnight, sinking large numbers of ships (the remains of which are still being uncovered by underwater expeditions to this day). Countless thousands of soldiers drowned, with plenty more left stranded and at the less than bountiful mercy of Japanese defenders.

The surviving Mongol commanders swiftly ordered a retreat to Koryo-dynasty Korea.

Thus the second, and final, Mongol invasion of Japan came to an end. Kublai Khan never abandoned the idea of another invasion, mind you, but by this point his health was ailing and he had more pressing concerns–in the form of brewing contention with other descendants of Genghis Khan looking to undermine his rule. When he died in 1294, his successors showed no interest in picking up his plans to invade Japan–there was no formal truce or anything like that, and for a few more decades the leaders of the Kamakura bakufu would remain weary of a third invasion, but in hindsight we can say that with the debacle of 1281, the threat of Mongol invasion came to an end.

Now, the defeat of the Mongol invasions of Japan is historically significant for a couple of reasons.

Of most immediate concern to the people of the time, it marked the beginning of a turning of the tide against Mongolian expansion. Alongside the 1260 victory of Mamluk forces over the Mongols at Ain Jalut in the Jezreel Valley of what’s now Israel, the 1274 victory represented one of the first real breaks in the aura of Mongol invincibility that had existed since the time of Genghis Khan. These defeats, in combination with the emergence of division within the Mongol ranks, meant the beginning of the end of the period of Mongol expansion.

However, in the longer term, the Mongol invasions have some other important legacies that are worth commemorating as well. First, for historians, they’re absolutely crucial in terms of the window they provide into Japanese warfare in the medieval period.

Previous conflicts like the Hogen and Heiji Rebellions as well as the Genpei War were chronicled either by period histories that don’t really talk much about the fighting itself, or by later gunki monogatari–romantic military tales that often contain some pretty extreme exaggerations, with the most famous example of course being the Heike Monogatari which depicts the Genpei War.

As a result, it can be hard for us to reconstruct exactly what fighting looked like in, for example, the Genpei War–we don’t have a lot of good sources for what actually happened when opposing armies clashed together.

The Mongol Invasions, by contrast, ARE very well documented–thanks primarily to one of their participants. This is, of course, Takezaki Suenaga, a man who needs no introduction because we once spent an entire episode on him (Episode 476, to be precise).

Because you can go back to Episode 476 to learn more about him if you are curious, I’m not going to go back over his history too much. Simply put, Takezaki was a lower-ranking samurai from Kyushu who participated in both the 1274 and 1281 campaigns against the Mongols.

After the 1274 campaign in particular, Takezaki felt his rewards for participating in the battle were inadequate–a situation about which we will have more to say in a second–and so he made his way to distant Kamakura, to petition a sympathetic shugo at the warrior capital to increase his rewards.

He was ultimately successful, and used part of his increased reward to commission an elaborately painted scroll known to history as the Moko Shurai Ekotoba– the illustrated scrolls of the Mongol Invasions, roughly translated.

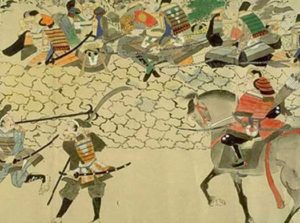

The text is a mixture of images depicting the 1274 and 1281 campaigns alongside text describing Takezaki’s involvement in the fighting. He intended it to be a record of his glorious deeds–and a dedication to the generosity of the shugo who rewarded him–but for historians it’s an absolutely invaluable text, because of Takezaki’s descriptions but also because of the detailed illustrations of fighters on both sides. Today, those images are used to research everything from the armor combattants on both sides wore to tactics and strategy.

There’s far more to the text and what it depicts than we could ever meaningfully do justice to here–if you’re interested, I highly recommend checking out episode 476, and if you can snagging a copy of Thomas Conlan’s excellent In Little Need of Divine Intervention, a great work on the Mongol invasions that deals heavily with the scrolls and which includes a translation of them. Just generally, Tom Conlan is one of three people I recommend anyone interested in English language scholarship medieval Japanese history check out (the others being Karl Friday and Mary Elizabeth Berry). All are great scholars with very approachable writing styles.

The Mongol invasions will have one other longer term legacy beyond their utility for scholars in allowing us to study medieval warfare–though Takezaki’s story is a great gateway to discussing it. I mentioned that what brought him to Kamakura was the belief he’d been insufficiently rewarded for service in the 1274 invasion. This was particularly important to him because those kind of rewards were, in essence, the main way that warriors were “paid.”

Elite samurai might own shoen or other land grants or receive minor stipends, but for the vast majority during this period their main form of income was battlefield plunder. After the fighting, individual warriors would often submit a list of their deeds–enemies killed, particularly those of importance to the opposing side, brave deeds committed, losses incurred, and so on. Those “bills for services rendered”, in essence, formed the justification of their compensation–more deeds done equalled more money in the bank.

In the past, this had worked well for a simple reason: if you were on the winning side, you could plunder the losing one. Lands, treasures, weapons, whatever–you could hand those out as rewards. But defeating the Mongols didn’t get the shogunate more lands, and what treasures the Mongols had with them generally ended up on the bottom of Hakata bay.

And it wasn’t just samurai who demanded rewards either; in the conception of the time, part of any war effort was the fervent prayers of religious institutions on your side, which could produce divine intervention favoring your soldiers. Temples and shrines too went hat in hand to Kamakura after the invasions, insisting–not unjustifiably, given the understandings of the age–that their spiritual efforts had helped defend the nation.

Covering these costs–rewarding all who had contributed–proved financially ruinous for the Kamakura shogunate. The sheer number of samurai demanding compensation, the cost of all the war preparations, drained the accounts of the bakufu to a substantial degree.

Which will help explain why, despite surviving the Mongol invasions and coming out with a stronger and more centralized government than had existed before, the age of Hojo rule was now less than a century from its end.

But that’s something we’ll come to in two weeks’ time. Next week, we’re going to return to the subject of medieval Japanese economics and social changes.

Hi Isaac, love the episode as always. I listen when I’m at work in between podcasts on learning Japanese-historical context is important for learning languages and you provide that quite well! I would like to add that this episode and the last few have had some weird audio quirks, in that the audio cuts out occasionally-only for the length of a syllable, but that does occasionally cut words in half.