This week, we’re taking a look at some of the economic and social structures of Kamakura period Japan in order to answer the question: just what makes medieval Japan so…medieval?

Also, I’ll be taking next week off for the New Year. See you all in 2024!

Sources

Oyama, Kyohei, “Medieval shoen“, Keiji Nagahara, “The Medieval Peasant”, and Kozo Yamamura, “The Growth of Commerce in Medieval Japan” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol III: Medieval Japan

Tonomura, Hitomi, “Gender Relations in the Age of Violence,” Thomas Kierstead, “Rise of the Peasantry,” and Ethan Segal, “The Medieval Economy” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850

Pearson, Richard, et al. “Medieval Japanese Trading Towns: Sakai and Tosaminato.” Available online here

Images

Transcript

Today, I want to put a pin in our narrative of the chronology of Japanese history to turn our attention to an important and related, but distinct, subject. We generally refer to the Kamakura bakufu as the beginning of Japan’s medieval era, and so we should take some time to talk about what that change means–what’s different enough about medieval Japan to make it, well, medieval?

The answer begins with a return to a discussion we’ve had before, regarding the shoen–the tax free estate.

As a quick refresher, shoen estates were initially created as a means to provide religious institutions with support, and to encourage private investment into the expensive and difficult process of clearing more of Japan’s mountainous land for agricultural cultivation.

Shoen lands, once granted, became in essence a permanent source of income for their holders–who did not pay taxes from their shoen to the central government, and who instead could collect taxes to sustain themselves from those who worked that land.

This is an arrangement that obviously greatly benefits the shoen holder–particularly because the rights are perpetual, meaning they do not ever expire and can be handed down to your descendants. You also didn’t need to manage your shoen in person–you could always pay a local manager to do that for you, and simply have them forward you the profits as you resided somewhere else (almost always in Kyoto or its surrounding environs). Nor was there any limit on the number of shoen an individual, family, or institution could hold.

Competition for them thus became EXTREMELY fierce, and in many ways it was this system of tax free holdings that created the unique governing structure of the medieval era.

This was a structure where multiple different centers of power–the imperial family, powerful aristocratic families, great temples and shrines, and now the various warrior families including the shogunate–held their own shoen. Those shoen provided the wealth for these independent groups to operate, and both justified the existence of and paid the financial cost for maintaining independent military forces to protect those land rights.

The proliferation of shoen–by the late Heian era, accounting for somewhere between 40-60% of taxable land–also substantially weakened the central government in Kyoto, which had a harder and harder time meeting its projected tax revenues from the ever decreasing amount of kokugaryo, public lands that were open to taxation.

This was a particular problem for the kokushi, provincial governors appointed by the Kyoto government to manage one of Japan’s 60 provinces–and whose main job was to meet the projected tax revenue for their tenure in office however they could.

In some provinces, this was harder than others; Noto province (now northern Ishikawa prefecture next to the Sea of Japan) had over 70% of its paddy lands converted into shoen by the 1200s.

Given the immense value of the shoen–particularly in a country where the economy was still overwhelmingly based on agriculture and would remain so for centuries–it’s not terribly surprising that shoen estates were worth fighting over. And during the medieval period, new contenders in the contest over their wealth emerged: the shugo, and jito.

These two positions collectively represented one of the most important concessions wrested from the civilian government by the Kamakura shogunate during its ascension.

Shugo, theoretically, were the samurai military counterparts to the civilian kokushi governors who oversaw Japan’s 60 provinces. They were supposed to handle issues of concern to the samurai class within the provinces–and to keep order among the fractious warrior families, who could be violently jealous of each other’s power and prestige.

Jito, meanwhile, were stewards appointed to individual pieces of land, often but not always shoen estates. In both cases, the goal was theoretically similar–the shugo and jito were intended to represent the interests of the samurai class, and to maintain order within the territory they’d been charged with, be it a whole province or an individual shoen.

The reality, of course, was quite a bit less smooth. It’s not entirely clear to us what the relationship was between the shugo and the various shoen estates–which among other things could not be entered by government agents without the permission of the shoen holder. Did that same rule apply to shugo, whose job included tracking down wanted criminals? The historical record is not totally clear on this point, but certainly we do see documented instances of shoen holders resisting shugo interference in their affairs.

It’s also pretty clear to us that the vast majority of shugo never even bothered taking up residence in the provinces they were assigned to, particularly if they were remote areas–after all, doing so would mean removing oneself from both Kyoto and Kamakura, the two places to be in terms of both culture and your personal political influence.

Realistically, shugo are important for us more for the precedent they set–samurai influence over affairs at the provincial level–than for their immediate effectiveness, which was questionable at best.

The jito, on the other hand, were a very different story–and one that’s extremely hard to tell because of how varied the story can be. The role of the jito, again, was to manage affairs for warriors in a given localized area–often defined by a shoen, though not always. And the charge of the jito was both broadly empowering and extremely vague. Their appointments were permanent and in perpetuity, revocable only by the Kamakura bakufu–and not answerable to the holder of a shoen estate or their deputies at all.

Jito were theoretically supposed to obey local precedents in terms of how they exercised their powers–but those precedents were often not well documented and at any rate left to the jito to discover.

This arrangement–a rather broadly defined job to “maintain order”, and complete independence from the existing arrangement of power within the shoen–made for a heady political cocktail. And indeed, the historical record is pretty clear that from the jump, jito clashed often with the existing powerholders wherever they were assigned–which is, in large part, why we know so much about them.

A good chunk of the Kamakura bakufu’s time and energy, particularly early in its history, was devoted to dealing with legal disputes between jito and shoen holders or between neighboring jito–the sheer number of problems an independent minded jito could create meant that a LOT of paperwork useful to modern historians was generated in the process of trying to keep them under some semblance of control.

As an interesting aside, the position of jito was also not a gendered one–it could be inherited by both men and women, and jito titles were not “combined” by a marital family unless that was explicitly agreed to as a part of the marriage (in other words, a wife could pass hers down separately from her husband).

It was not until the Mongol invasions when this changed. Women in the warrior class certainly contributed to the war effort, but few of them fought on the frontlines–and the shogunate explicitly condemned this, ordering in 1286 that women no longer inherit landed titles in Kyushu until the threat of a third invasion permanently passed. Families without a male heir to inherit their lands were to adopt one immediately.

That order was never rescinded, but neither was it consistently followed–enforcing such things in remote Kyushu was difficult, and at any rate few families were terribly keen to adopt new heirs who weren’t necessarily loyal to the family just because the shogunate told them they had to. Still, this was the beginning of an official clamp down on female inheritance among the samurai class–alongside shifts in the inheritance patterns of the time which we’ll talk about in a second, this was the beginning of a shift for warrior women into a distinctly second-class status.

And by the way, I do also want to note that while women don’t appear much on the frontlines of battle during this time, there is evidence to suggest that the women of the warrior class did fight. Of course, the example of Tomoe Gozen–a minor character in the Heike Monogatari, who is depicted as a follower of Minamoto no Yoshinaka and who does some pretty badass stuff before riding off into the sunset, is illustrative–though it is unclear, as with so much of Heike Monogatari, how fictionalized this all is.

Similarly, there’s an offhanded reference in court documents from the Nanbokucho wars–about which more starting next week–to a “female cavalry”. Unfortunately, said document says nothing else about them.

Even during the massive wars of the 1500s, there are accounts of women fighting–primarily to defend their homesteads while men were away on campaign. For example, one witness to the siege of Amakusa castle in 1589 said that the women of the castle fought back so fiercely that, “they filled the moat with the bodies they slew.”

Anyway–all of this is interesting, but a bit beside the point. Suffice it to say that both men and women had the ability to inherit these titles during the Kamakura period, and fiercely defended their ability to do so.

You see, regardless of their relative levels of power, the positions of both shugo and jito were highly coveted, for a simple reason. You see, it might seem a bit counterintuitive, but it’s worth remembering that at this point there’s not really a sharply delineated warrior “class”–the samurai are not a distinct social category in the way they will be in later years. Before the Kamakura period, warriors were also local officials, tax collectors, and anything else they had to be to make a living–and were dependent on the continued good will of local officials or employers in the various estates to keep their jobs.

One of the main ways Yoritomo and his immediate successors won their followers was by promising, in essence, job security–with the positions of shugo and jito, functionally lifetime tenures dependent only on the goodwill of the shogun, being one of the main ways they made good on the bargain.

However, even with these new positions the issue of satisfying warrior demands for land never really went away, and in retrospect this would become one of the key structural weaknesses of the Kamakura shogunate and a massive contributor to its eventual downfall.

As I’m going to keep saying for…well, at least a dozen and change more episodes, the economy of Japan at this point is overwhelmingly agrarian, meaning that land rights are the main way a person makes money. Thus, when Minamoto no Yoritomo and his successors took it upon themselves to organize the warriors of eastern Japan into a coherent political force, one of the main demands of those warriors was for more land.

And early on, satisfying that demand was not too difficult. Yoritomo could redistribute lands from the defeated Taira as well as other foes, and his successors had no shortage of opportunities to do the same.

For example, both the crushing of the Hiki clan by the Hojo in the first decade of the 1200s and Emperor Go-Daigo’s Jokyu Rebellion in 1221 saw massive redistributions of land to pro-Hojo families once the shogunate won out.

However, over time this sort of redistribution became harder and harder to manage, for the simple fact that military challenges to the shogunate became comparatively rare. The last serious rebellion against the shogunate was in 1247 (by a retainer family called the Miura who hoped to forge an alliance with the Kyoto court to challenge the Hojo).

After that point, opportunities to crush a military challenge (and thus redistribute land to favored retainers) were fewer and further between–and new medieval farming technologies had reached their limits in terms of bringing new lands under cultivation.

You might be asking: why is there this insatiable demand for more and more land among the warriors of Kamakura? At what point would enough be enough? Well, partially, this is a matter of politics–each successive generation of leaders needed favors to give out to win support, after all.

After all, relying on good policy to convince people to follow you is all well and good, but sometimes you just need a bit more of a…traditional incentive, shall we call it?

But more important than sheer political bribery was inheritance practice. Before the 1300s, it was actually relatively uncommon for warrior families (or anyone else) to engage in primogeniture–the inheritance of family assets by an eldest male heir.

Instead, from what we can tell, assets appear to have been split between all children, often but not always including daughters.

Which was wonderfully forward thinking and all, but meant that the estates of these powerful families were constantly fragmenting, and thus needing to be replenished.

Eventually, this would result in a shift towards primogeniture and single male heirs for families–but that shift would take a lot of time, both because changing social customs always does and because potential heirs would, naturally enough, have some feelings about the issue.

And a single heir being, well, one person meant that barring some serious family tragedy there were always going to be more people invested in fighting that sort of shift than supporting it.

In the intervening years, warrior families attempted stopgap measures–for example, lifetime inheritances that would go to children other than the oldest male and then revert to the main family line after death.

However, in general warrior families were constantly losing income due to inheritance practices.

The constant battles for wealth shaped the nature of warrior society during the Kamakura period. They were also a big part, for example, of why the jito position could be such a legal mess–more than a few families who had inherited jito titles tried to make up for shortages in income created by inheritances by keeping more taxes from the estates they were “guarding” than they were entitled to.

And that wasn’t even really something the estate owners could do all that much about; their only recourse was to complain to the shogun in Kamakura, enacting a lengthy and complex court process that could take years to resolve–and which the shogunate often had a hard time enforcing anyway.

Some jito families even took up banditry when they lost a court case against an estate holder–in essence, continuing to collect taxes and daring the government to stop them.

And rarely, if ever, were they actually stopped.

All of this meant that land rights and wealth were an increasingly contentious subject during the Kamakura period. As we mentioned last week, the great victories against the Mongols didn’t result in more lands or wealth to redistribute either, so paying back warrior families for their service often involved dipping into the shogunate’s own reserves.

And this was a distinctly dangerous situation to be in. Remember, the warriors of eastern Japan had come to follow Minamoto no Yoritomo largely not out of personal allegiance, but because of the practical promises he made them–join me and we can become a political force to reckon with, and that force can be wielded to protect your interests and wealth.

If the Kamakura government could no longer guarantee great rewards for its followers in the way it once had, well, maybe it was not quite as useful as it once had been.

When we look, next week, at the rapid collapse of the Kamakura government, I think this will be important to keep in mind. As we look for explanations for why that government would collapse so rapidly in the face of a military challenge from the seemingly defanged Kyoto government, it’s important for us not to ignore in many ways the most obvious explanation: the Kamakura government collapsed because its most important constituents had stopped seeing the point or value of it.

But of course, warrior interests are not the only important part of this period, and I want to leave the samurai where they are for a bit to turn our attention to another subject: the lives, of, well, more or less everyone else.

Because while we’ve been dealing mostly with the lives of warriors, aristocrats, and priests, these people were comparatively speaking a tiny fraction of Japan’s population–estimated, by the year 1100, to be somewhere between 5.6 and 7 million people.

For comparative purposes, the higher of these two numbers–7 million people–is about ½ the population of Tokyo proper today (14 million people)–which by the way is JUST the 23 wards of Tokyo itself, not counting the greater metro area (which is of course quite a bit bigger.

Anyway–all of that’s to say that our focus has primarily been on a tiny fraction of a comparatively much smaller population than what exists now. And there’s a good reason for that, of course–literacy.

Literacy, in Japan as everywhere else, was far from universal before the advent of modern public education, and in particular during the medieval era literacy was not common at all. Only those who could afford an education–which is to say, the upper levels of the samurai class and the Kyoto aristocracy–reliably knew how to read and write. Those who made it into the Buddhist priesthood, meanwhile, would learn as well–after all, you had to know how to read in order to chant a sutra–but that group too represents a fairly small substrate of society.

Meanwhile, the vast, vast majority of Japan’s population at this time belonged to none of these groups–they were, instead, farmers.

Our knowledge of medieval peasants is limited, to say the least–it would not be for a few centuries yet that literacy would begin to penetrate substantially into the countryside. In the written record–which represents the single greatest collection of sources available to a historian–medieval peasants appear rarely, and when they do it’s pretty much always through the eyes of other social classes who did not have a particularly high opinion of them.

In addition, those records almost entirely deal with subjects of dispute, primarily in relation to land and taxes. From what we can tell, most of the interactions of peasants in the countryside with the literate elites of the cities revolved around issues of taxation–those owed taxes complaining that they weren’t getting enough, and the peasants complaining that too much was being asked of them.

This skews our perception even further; if the written record is to be believed, legal battles with shoen proprietors and local warriors over their produce was the secondary vocation of all farmers after farming itself.

Given that the ones collecting taxes are the ones writing these records, they’re also not very favorable to the peasants–depicting them as duplicitous, more interested in the avoidance of their justly owed taxes (from the perspective of those owed said taxes) than anything else.

Indeed, in many ways as time went on the separation between elites writing history and peasants living through it grew stronger. Recall that most aristocrats and elite warriors during this time are drawing their income from shoen estates. Doing so, however, explicitly did not require actually living on said estate–the vast majority of estate proprietors farmed out the job of actually running their estates to locals called shouken, who did the actual managing and forwarded the profits on to the owners (minus their take, of course).

All of which meant the people doing the most writing of the historical written record would, in many cases, never see a peasant except from afar on a pilgrimage route or something similar.

There’s also the confusing fact that, during this period, written records don’t really distinguish between farming and other non-elite professions. There was no legal distinction, for example, between a farmer living on a shoen and a local merchant who might move between a few neighboring estates to make a living. Nor was there any special system to tax the transactions of said merchant–they were treated as a part of a farming family and owed taxes based on the size of said family and their family lands.

Similarly, produce like fish or salt would be assessed in an equivalent value of rice–an extremely gameable system in an age before modern commodity markets.

Which was nice if you were a local–after all, it made figuring out the taxes you owed quite a bit harder. But it definitely makes our jobs as historians a bit more challenging.

We’re not entirely reliant on traditional written records, to be sure. One particularly famous example is an emaki, or illustrated scroll, depicting the life of the founder of Pure Land Buddhism, Hounen–the Hounen Shounin Eden.

Hounen, you might recall, was exiled from Kyoto at one point due to concerns about the unorthodox teachings of his sect; this scroll includes a depiction of his time in the countryside preaching to the locals while they are farming.

He himself is the focal point of the scene, while the farmers do the work of transplanting rice seedlings into paddy fields. Men are shown preparing the fields while women work behind them transplanting the seedlings, with some percussionists equipped with drums and a rattle providing an accompaniment–presumably as a way to keep time and keep spirits up during the difficult work.

That scene is pretty famous–it’s the basis for the farming scene at the end of Kurosawa Akira’s epic film The Seven Samurai, for example, symbolizing the bonds of village life and the return of peace–but there’s no way of knowing how accurate it is. After all, the artist in question was mostly interested in depicting Hounen’s life; they could have just made the scene up altogether.

What we’re left with, then, is an attempt to read out the history of the vast majority of Japan’s population from the margins of the written record itself–reconstructing what we can from offhanded and fragmentary references.

That situation, mind you, is nowhere close to unique to Japanese history. Indeed, the last few decades have seen a massive interest in trying to do similar work around the world–where, for the exact same reasons, the written record (where it exists) overwhelmingly favors the elite and well-educated.

The picture that emerges when you begin to do this is fascinating–because it implies that peasants were far better at organizing themselves than their elite counterparts gave them credit for. For example, a 1334 record of Niimi estate near modern Okayama in Western Japan provides a fascinating window into tax collection–it was assembled by a monk named Jinson, whose temple owned the estate and who was charged with ensuring taxes from it were being properly collected.

Jinson’s document details all the usual information you’d need, but in doing so provides a fascinating window into rural life. For example, one of the expenses listed for the estate is a new year’s banquet thrown by the estate manager to which all the peasants of the estate were invited–given that this is treated as, in essence, a business expense that is tax deductible, this seems to have been a social expectation for estate owners.

Similarly, the document makes reference to “market dwellings”–primarily in the context of taxation, as these market dwellings have fields attached to them from which taxes are to be collected.

However, this gives us a clue that even a small estate like Niimi held a market town–which in turn implies trade with neighboring estates.

Fragments like this provide us a hint of what was happening out in the provinces, but they are just that–fragments. Unfortunately, a better understanding of life in the provinces would have to wait for a few more centuries yet.

More broadly, we can look at the economy of medieval Japan and make some interesting inferences.

And I do have to emphasize that here too we are very reliant on inference; the historical record is not as thorough when it comes to, say, the spread of coinage or the growth of commodity markets as it is when it comes to wars and succession disputes.

And at any rate these things lack hard and fast dates associated with them in quite the same way that, say, a war has a definitive beginning and end.

Still, there are some distinct shifts in the economy that we can observe over the course of the medieval era, and if we can’t pinpoint exactly when they took place they still serve as valuable illustrations of how much was changing–and how quickly.

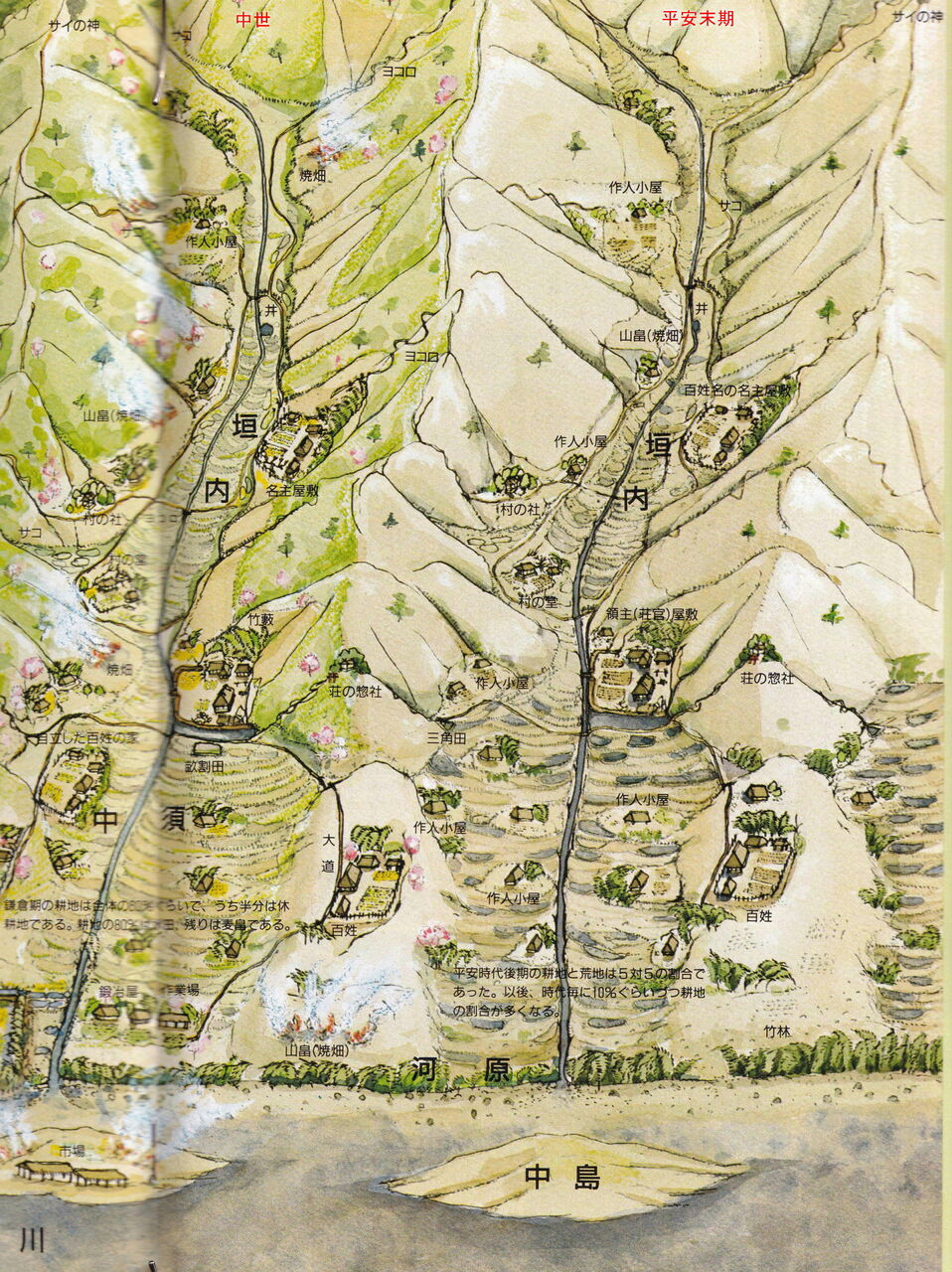

For starters, it’s pretty clear that agricultural productivity did begin to expand over the course of the 1200s–and especially 1300s. In other words, while bringing new lands under cultivation–the traditional way of growing the agricultural economy–was harder to do, the lands that were being cultivated were becoming substantially more efficient.

There are a few reasons why. One of the biggest is the import of a new strand of rice–so-called Champa rice–from the continent. Originally from what’s now Vietnam, this strain of rice is much more drought-resistant and hearty, and tends to mature more quickly than earlier variants. It was introduced to China some time in the Song dynasty (so about 1000 years ago), and arrived in Japan a few centuries later.

The second big shift was a series of improvements in irrigation. If you’ve ever seen a rice paddy, you know they take a LOT of water to maintain. In prior centuries, Japanese farmers had mostly relied on natural irrigation to do this; however, by the medieval period they’d developed new techniques to make irrigation easier and more consistent. One of the biggest was the development of artificial reservoirs to control irrigation, including “saucer ponds” designed to collect runoff from rainwater and use it to irrigate fields.

These improvements, plus the increasing availability of draft animals and the discovery of double-cropping–planting twice on a field in the same year by relying on crops that matured in different seasons–meant that agricultural productivity began to explode in the countryside over the course of the medieval years.

And importantly, very little of that increased productivity was successfully taxed by shoen estate holders, provincial governors, or anyone else.

For starters, tax rates were fixed as a certain amount per field–with the assumptions that number was based on being rooted in earlier and less productive farming methods. In addition, remember that most shoen estate holders were absentee landlords, and even a provincial governor would rarely go wandering about the countryside surveying the landscape personally.

In addition, the Kamakura shogunate actually forbade members of the warrior class–who usually DID live in the countryside–from taxing the second harvest of peasants–not out of kindness, mind you, but because of worries around famine.

So it was comparatively easy to keep the benefits of this growing productivity within the farming communities themselves. And that, in turn, led to a profound shift in the nature of the Japanese economy.

Because, well, imagine: if you have more of something than you really need, what are you going to want to do with it? The answer, of course, is sell it.

And so, in the countryside, you see the beginning of proliferation of local markets–as hinted at, for example, in the records of Niimi shoen we talked about in this episode.

Of course, markets were not new to Japan–there are scattered references to local markets as far back as the Nara period. But they’d been comparatively small in number, with most of the economy, from what we can tell, being run through the center of power in Kyoto.

The medieval economy, by contrast, was like almost everything else in medieval Japan far more decentralized, with growing trade not just between the provinces and Kyoto but within the provinces themselves. And unlike past eras, this economy was mediated by a growing new form of exchange–currency.

Now, there had been attempts by past Japanese governments to mint their own coinage as far back as the pre-Nara years, but for various reasons we don’t really have time for this never really took off–the biggest, if you’re curious, was simply that when most of the economy revolved around shipping goods from the provinces to Kyoto, coins just weren’t that useful.

So Japanese coinage would fall off in usage–and wouldn’t really return until the 1590s. Instead, it was foreign coins, specifically currency brought over from China’s Song dynasty, that formed the backbone of the economy. These Chinese coins were incredibly valuable, and there was massive demand for them in Japan as the rural economy grew. The demand was such that the Song dynasty eventually placed a (not very successful) ban on the export of coins to Japan.

Song dynasty coins would remain the main medium of exchange until the 1500s.

The upshot of all of this was the emergence of provincial market towns–the beginning of urbanization outside of Kyoto and Kamakura. These early market towns were generally built on or near the grounds of a local Buddhist temple, both because the temples attracted pilgrims as visitors and because their influence could shield the market from interference by local warriors or officials.

There was also a belief that temples could spiritually cleanse an item, so to speak, of attachment to its former owner–preventing any unfortunate pollution from following an item to its new owner.

These market towns would become increasingly important to Japan’s economic and cultural life as they continued to grow, becoming home (for example) to the nation’s first trade guilds and to growing numbers of professional artisans and merchants.

They remained, for the time, comparatively small in scale–but as we’ll see, their importance will only increase as the years go on.