This week: the rise of the Minamoto clan, the destruction of the Taira clan, and the birth of a new kind of political arrangement in the form of Japan’s first shogunate.

Sources

Friday, Karl F. “Dawn of the Samurai” and Andrew Edmund Goble, “Kamakura Shogunate and the Beginnings of Warrior Power,” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850.

Takeuchi, Rizo, “The Rise of the Warriors” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol II: Heian Japan

Mass, Jeffery P. “The Kamakura Bakufu” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol III: Medieval Japan

Images

Transcript

When last we left things, the ascendant warrior class of Japan had become major players in the kenmon system–the system of decentralized power centered on wealthy families or institutions who collectively managed the imperial state.

Thanks to the Hogen and Heiji Rebellions of 1156 and 1160, it had become clear to basically everyone that going forward, warrior power was going to matter a lot in politics–and that you couldn’t just assume said warriors would be easy to control for your own purposes.

Indeed, those very warriors had shown a willingness to engage in shocking breaches of the non-violent rules of engagement that had dominated Kyoto politics for centuries. Previous competitions for power had been brutal, yes, but generally solved with an exile or two. Now, instead, palaces were being burned, heads were being displayed–there were, in essence, no rules anymore.

And in this violent struggle, the man who had emerged on top was one Taira no Kiyomori, scion of the Kanmu Taira family and, after crushing the Minamoto and Northern Fujiwara militarily, pretty much the undisputed master of Kyoto.

After defeating his rivals in 1160, Taira no Kiyomori had busily set about securing the power of the Taira family, establishing it as the pre-eminent force in Kyoto politics. If the Kenmon system we talked about last week was all about rival families using their independent wealth and power to fight for control over the imperial administration, Kiyomori was able to fight those battles far more effectively than anyone before him.

He packed the imperial bureaucracy with allies and relatives–especially relatives, because the politics of this time were deeply grounded in familial alliance–and had himself promoted up through the ranks of the state bureaucracy. In particular, in 1167 he became the first person outside of the most elite families of the Kyoto aristocracy to be granted the title of daijou daijin, the grand councilor of state and the highest position open to someone not a part of the imperial family.

In 1171, he was able to take this prestige one step further–he arranged for his daughter, Taira no Tokuko, to enter the household of the then-reigning emperor, the then 12-year old Takakura. Seven years later, the two would have a son–setting things up so that before long, a half-Taira emperor was likely to be sitting on the imperial throne.

And indeed, in 1180, Kiyomori would get his wish, forcing the sitting emperor to abdicate in favor of Kiyomori’s grandson, known to history as emperor Antoku (all of 2 years old at this point).

Of course, all this Taira ascendancy was secured by a key political alliance; Kiyomori’s closest friend at court was the retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa, a longstanding ally of the Kanmu Taira (as many a retired emperor before him had been).

I think historian Andrew Goble puts well what’s important about all this: “[Kiyomori realized] that warriors now had a role in court politics and that he controlled those warriors.

That said, he did not support greater authority for provincial warriors. Instead, he became a new stakeholder in the existing central aristocratic polity, and he built the same type of patronage and family networks familiar to Kyoto power brokers: He obtained provincial governorships for himself and supporters, acquired provincial land rights, built marriage ties to the imperial family, and seems to have seen new opportunities for wealth from overseas trade.”

In other words, Kiyomori did not try to leverage his control of the warrior class to upend the existing aristocracy in favor of the warrior class as a whole, but simply to add himself (and his family) to that existing aristocratic system as the first among equals.

Naturally enough, however, Kiyomori’s ambitions began to draw more and more resentment his way, as existing aristocrats came to resent the impediments to their authority presented by a man who was not from a great family and who relied on such brutish methods to seize power.

Kiyomori reacted to challenges to his authority with extreme harshness; a plot by members of the Northern Fujiwara to oust him in 1177 was broken up when it was reported to his supporters, and the ringleaders either placed under permanent house arrest or publicly beheaded. Over time, even the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa began to express concern about Kiyomori’s power;he’d become increasingly worried about his erstwhile ally Kiyomori and come to see Taira power as a threat to his regime.

Kiyomori responded to this concern by placing the retired emperor under house arrest too–essentially, launching a coup of his own to seize complete control of the Kyoto government. He later moved to secure that power by attempting to relocate the capital out of Kyoto for the first time in centuries–following in the footsteps of predecessors like Emperor Kanmu, who hoped that by moving the center of administration closer to their own base of power, they could exercise even greater degrees of control over the state.

Specifically, Kiyomori relocated the capital to Fukuhara-kyo, now more or less Kobe just northwest of Osaka. The move proved disastrous; the site was too cramped to fit the necessary buildings, and too wet from storms blowing in from the inland sea. The project was abandoned in less than six months in favor of a return to Kyoto–but the attempt itself showed the lengths to which Kiyomori would go for power.

Still, it wasn’t like anyone could effectively challenge Kiyomori’s power. Just before the relocation of the capital–and in fact this was one of the inciting incidents of the move–a young prince of the imperial line named Mochihito, the son of Go-Shirakawa, had attempted his own strike against the Taira; he sent a missive out to the other warrior families of Japan calling on them to join him in destroying Kiyomori, who had usurped the dignity of the imperial throne.

That message fell largely on deaf ears; outside of the Taira, very few warrior families had much of a stake in the court politics of Kyoto, so why would they join a rebellion that could cost so much when they didn’t really have a lot at stake?

Besides, it wasn’t like victory looked particularly certain. Mochihito also sent his appeal to the powerful monasteries of central Japan, particularly the feuding temples of Enryakuji and Miidera at Mt. Hiei and the great temples of Nara. These temples too were players in the Kenmon system; they were wealthy and powerful in their own right thanks to shoen grants, and even had armed followers to defend their claims.

However, when several of the monasteries of Nara as well as Miidera did take up arms, they were crushed by the Taira in a battle near modern Uji southeast of Kyoto–and Kiyomori responded by burning Miidera and a good chunk of Nara to the ground.

Prince Mochihito himself was killed in the fighting.

So Taira ascendancy didn’t look like it was going anywhere, except for one of those funny twists of fate. Remember how two of the children of the old Minamoto clan leader, Yoshitomo, had been spared execution and were still alive?

Well, the elder sibling, Minamoto no Yoritomo, was out east in the Kanto in 1180 with the Hojo clan, a Taira ally to whom he’d been entrusted to make sure he didn’t cause trouble. Yoritomo was clever and charismatic, and his erstwhile captor Hojo Tokimasa liked him enough that he’d allowed Yoritomo to marry his daughter, Hojo Masako.

Now, Yoritomo was theoretically disempowered: away from his family, surrounded by Taira loyalists in the distant east far from the center of political power. But this, in fact, turned out to be quite an asset; Yoritomo had twenty years to become familiar with the politics and concerns of eastern warrior society, divorced from the remote goings on of the Kyoto government about which the warriors cared very little in practice.

And this familiarity, plus his distinguished lineage and his marriage to Masako, were substantial assets when news of Prince Mochihito’s call to arms reached the east (well after the prince himself had died fighting the Taira). Yoritomo began to use it to make the case to his fellow eastern provincial warriors that Mochihito’s call to arms was a valuable opportunity. The warriors of the east (with him as their leader, naturally) could use it as a pretext to construct a new order where united samurai families of the oft-neglected eastern provinces could come together to make themselves a political force, and to protect the property rights and alliances they built their own power on from interference by a court that only ever used them for its own ends.

And this message–nobody in Kyoto cares about you, but together under my rule we can make them care–found a willing audience.

Admittedly–and understandably, given how previous military efforts against the Taira went–finding warriors willing to rise up against Taira power proved a bit of a challenge. The very first battle between Yoritomo’s allies and a Taira force sent to deal with them (in the foothills of Mt. Fuji in the late summer of 1180) ended in a Taira victory, with Minamoto forces driven from the field by superior numbers. However, Yoritomo was able to make a fighting retreat, and gather more allies from the mountainous interior of the east (in particular, the Takeda clan–who will come up in the future). With their help, Yoritomo was able to counterattack and drive the Taira forces from the east in the fall.

That victory in turn gave Yoritomo some breathing room to secure his position in the east among the clans of the area. From a home base in the village of Kamakura, Yoritomo began to assemble a following of eastern clans who, now that he had proven he could win, were increasingly willing to listen to what Yoritomo had to say.

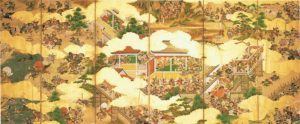

The resulting war is known to history as the Genpei War, a combination of the Chinese readings of the characters for Minamoto (Gen) and Taira (hei, or pei).

This is also, by the way, why you sometimes see the Minamoto called the Genji (a Chinese style reading of the characters for “Minamoto clan”) and the Taira the Heike (a Chinese style reading of “Taira family). For clarity, I’m going to consistently use Minamoto and Taira going forward.

And from this point on in the Genpei War, pretty much everything came up Minamoto. Yoritomo himself was more of an administrator than a commander, but his cause was helped substantially by the re-emergence of his younger half-brother Yoshitsune–the one who had been carted off to a monastery.

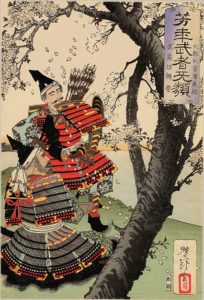

Minamoto no Yoshitsune is such a titanic figure of legend and literature, and his exploits have been so thoroughly mythologized that it’s often genuinely hard for the non-expert to sort fact from reality. That task is entirely beyond the scope of this podcast; for us, it’s important simply to note that Yoshitsune WAS an excellent field commander, and that with his help Yoritomo and the Minamoto side were able to score a series of decisive victories over the Taira.

By this point, Kiyomori himself was gone from the scene–he’d taken ill in late 1180 shortly after defeating the temples that had joined in Prince Mochihito’s rebellion and died shortly thereafter.

His death was cast by some as an instance of karmic punishment for attacking Buddhist institutions; in the famous dramatization of this period Heike Monogatari, he is wracked with a literally hellish fever that cannot be cooled and which burns all who comes near him before his death, reflecting the sure punishment he will experience in Naraka, the Buddhist realm equivalent to Hell.

Somewhat over the top depictions notwithstanding, without Kiyomori’s leadership the Taira suffered badly. His heir Taira no Munemori proved both a less adept commander and a worse politician, and under his leadership Taira forces collapsed swiftly–even though the Minamoto themselves splintered during the war, with some coming to back Yoritomo’s cousin Yoshinaka, who separately declared war against the Taira and was the first to drive them from Kyoto.

Yoritomo cleverly allowed Yoshinaka to handle the bulk of the fighting against the Taira while he concentrated on strengthening his hold over the warrior families of the east, and then swooped in to crush Yoshinaka after his cousin had done the hard work of seizing Kyoto.

There’s a LOT of complexity to the war and avid listeners or readers of Heike Monogatari will know I am skipping over a LOT–but the upshot was that by 1185 the Taira clan was annihilated. Its final stand was at Dan-no-ura near the straits of Shimonoseki, dividing Kyushu from Honshu, where the Taira had fled with the boy emperor Antoku and one of the pieces of the imperial regalia (Kusanagi no Tsurugi, the sword).

Supposedly, when it was clear the battle was lost, Taira no Kiyomori’s widow Tokiko took the then seven year old boy and the sword, and jumped into the water, drowning the two of them and taking the sword with them.

There are various legends about the sword magically returning to Kyoto, but more likely it was simply replaced.

The death of the Taira leadership brought the war to a close–Minamoto no Yoritomo was now the most powerful warrior in Japan, and thanks to the coalition of eastern warriors he had constructed he was arguably the most powerful man in the country too.

And this is really the most important thing about Minamoto no Yoritomo. Again, he wasn’t a great military commander–not an awful one, but not great either. But he was a smart (if ruthless) politician, who carefully handed out prizes and honors to his followers in order to build a network of personal relationships that supported his rule.

More ruthlessly, he was not the type to make Kiyomori’s mistake and spare anyone from the Taira clan, even if they were young–after all, who knew better than him how that sort of mercy can come back to haunt you later?

He even turned on his own half-brother Yoshitsune after the war ended, who had been his most able commander–and who, for that reason, had to be crushed after the war lest Yoshitsune’s popularity prove a threat to his own rule.

Yoritomo spent the seven years after the fall of the Taira cleaning up little threats to his rule like this and waiting for the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa–the last political counterweight to his influence–to die. When Go-Shirakawa finally did in early 1192, Yoritomo took advantage to begin pressuring the new head of the imperial line, the retired emperor Go-Toba, to grant Yoritomo a new position.

Specifically, Yoritomo received the title of shogun–that old position used to indicate commanders for the armies subjugating the Emishi tribes of the north–but made use of it in a new way. This was to be no temporary appointment–Yoritomo would hold it until his death in 1199, and arrange for it to be passed on to his son–and it was to be an administrative role rather than a military one.

Yoritomo is thus the founder of Japan’s first bakufu–literally, “tent government”, a term that refers to the various governments established by the shoguns of Japan. We call his government the Kamakura shogunate, after the eastern outpost that had become the Minamoto family headquarters during the Genpei War.

Now, the government structure Yoritomo set up was pointedly NOT designed to completely displace the existing one in Kyoto–like Kiyomori before him, Yoritomo saw a value in maintaining the existence of the old system and using it to legitimate his own rule. Instead, Yoritomo used his new title and the administration he built to carve out more political power for the warrior class–and to dispense power and rewards to his followers in order to ensure their loyalty.

If we return to the language of previous episodes, Yoritomo is setting himself up as the master of a new kenmon, an independently powerful institution with himself at its head–and using that independent power base to control aspects of the government to his own advantage.

For example, one of the concessions Yoritomo was able to wrest from the Kyoto government for “saving them from Taira domination” was the ability to appoint shugo, or military governors, in Japan’s 60 provinces. Ostensibly these shugo would be parallel figures to each province’s kokushi, the provincial governor appointed by the civilian government in Kyoto. The kokushi would handle matters of civilian interest–taxation being the most important–while the shugo would handle military issues like banditry, and manage the needs of the local samurai population.

In practice, the line between civil and military affairs was not always clear, and clashes between civilian kokushi governors and military shugo ones were not uncommon–with the result generally favoring the military side.

Similarly, Yoritomo was empowered to appoint jito, or stewards, to the nation’s tax-free shoen estates. These jito stewards, often chosen from the ranks of Yoritomo’s own vassals, were tasked with maintaining law and order in the estates, whose smooth functioning and regular supply of taxes were after all essential to the needs of Yoritomo and the government more broadly. Theoretically, the jito were supposed to work with the existing powerholders of estates–the shoen holders and their appointed managers–to make sure things went smoothly. Practically, the jito often butted heads with shoen owners, and once again they usually came out on top.

What Yoritomo is setting up with moves like this is, in essence, a two-tiered government split between the civilian center in Kyoto and his military one in Kamakura. And while over time the military side would come to dominate politics in ever increasing ways, the civilian government would not be totally disempowered–at least, not yet.

Yoritomo’s two tiered government, however, would not remain long in the hands of the Seiwa Minamoto. After his death in 1199, power would swiftly slip away from the Minamoto clan.

And to talk about why, we have to talk a bit more about some good ol’ fashioned family politics.

You might recall that one of the most important parts of Yoritomo’s rise to power was his relationship to his marital family–the Hojo clan, one of the eastern warrior clans of the Kanto. Yoritomo had been entrusted as a boy to Hojo Tokimasa, the head of the Hojo clan and a longstanding political ally of Taira no Kiyomori–the thinking being that as Kiyomori’s ally, Tokimasa could be trusted to keep an eye on the boy and ensure he didn’t cause trouble.

And at first, this worked–but over the course of the 1170s, Tokimasa’s loyalties began to shift. It’s a bit unclear why; it’s not like he kept a diary or anything talking about his political loyalties, or if he did we don’t have it. Likely one of the inciting incidents was the marriage of his daughter Hojo Masako–who ignored her father’s initial wishes–to Yoritomo in the late 1170s; again, we don’t have much in the way of sources in terms of the interpersonal dynamics here as to what led either Masako or Tokimasa to start to see Yoritomo as an ally.

For example, the Azuma Kagami–the history of this period–begins in 1180 and describes Tokimasa as already loyal to Yoritomo at this point.

We can certainly theorize; it seems likely that both Masako and Tokimasa gradually came to view Yoritomo as potentially useful to them given his charisma, political talents, and his elite pedigree as a part of the Seiwa Minamoto.

Regardless–by the time the Genpei War began, the Hojo clan was firmly in the corner of Yoritomo and the Minamoto, with both Tokimasa and Masako serving as two of Yoritomo’s closest advisors. They would remain so until his death, at which point a funny thing started to happen.

You see, Yoritomo had two sons by Masako when he died: Yoriie, the eldest, was 17, and Sanetomo, the youngest, was 7. Neither was quite ready for the reigns of power, and so Yoritomo’s death triggered a crisis of leadership within the shogunate that lasted for a quarter of a century. You see, the shogunate had already proven its value in just seven years as a vehicle for the influence of eastern warrior families over politics–but said families were also notoriously independent and jealous of one another, and both disinclined to listen to young kids or to allow one of their own to replace Yoritomo.

They were all, after all, supposed to be equals.

So, ok, that’s fine–we can just prop up the kids as a symbol to replace their dad in the role of shogun. But that still leaves a problem; they’re kids. They’ll need a guiding hand to ensure they are able to manage things. So, who is the guiding hand going to be?

That question would take several decades to solve, and the answers would involve a not insubstantial amount of political violence.

To start with, the eldest of Yoritomo’s children, Yoriie, assumed the mantle of shogun after his father’s passing. At 17, he was at least nearing adulthood, and conveniently already had a son, the 1 year old Minamoto no Ichiman.

He was also a talented warrior with a substantial interest in fencing and archery, which would be useful for impressing his warrior followers.

But his heir (and his marriage) were also a point of controversy. His wife, Wakasa no Tsubone, was the daughter of Hiki Yoshikazu, head of one of those elite warrior families of the east, the Hiki. And that, along with Yoriie’s youth, led to concerns that Yoriie’s role as shogun wasn’t really to rule, but to serve as a conduit for influence on the part of the Hiki clan.

That worry was particularly prominent for Hojo Masako and Hojo Tokimasa, who were worried about losing influence over their son/grandson respectively in favor of his marital family. And so they arranged a coalition of anti-Hiki families who worked against Hiki influence. Ultimately, Tokimasa would decide to deal with the problem permanently, inviting Hiki Yoshikazu to a meeting in 1203 and then assassinating him when he arrived.

At the same time, Tokimasa had the shogun himself placed under house arrest “for his own protection” while a Hojo led coalition destroyed the Hiki permanently. Tokimasa’s own great-grandson (and Yoriie’s son) Minamoto no Ichiman, who as tradition dictated was with his maternal family, was killed in the fighting at the age of six.

Yoriie obviously did not take this terribly well, and died under mysterious circumstances (almost certainly also killed by his own grandfather) the next year.

So, ok, that didn’t go great, but Yoritomo had another son–Sanetomo, who is at this point 12, so a bit older, and we can put him up as shogun and that should work ok, right?

And it did….sort of. You see, at this point the Hojo clan started turning on each other, with Tokimasa and his daughter Masako each becoming convinced the other was planning to cut them out of political power. Masako acted first, and in 1205 launched a mini coup of her own with her brother to remove her father from his positions and take the reigns of government for herself. Masako, through her son, would largely be calling the shots on behalf of the Hojo going forward, spending the next few years cooking up pretexts to remove other warrior families of the east she saw as a threat (or at least, insufficiently pliable to her rule).

But then, in 1219, disaster struck again; while in Kamakura visiting his family’s shrine (Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine), the shogun Sanetomo was killed. By who, you might ask?

His own nephew!

You see, Yoriie, the previous shogun, actually had two sons–the older, Ichiman, was killed, but the younger one, who was three when his maternal family was purged, was not, and was instead packed off to a monastery where he would presumably not be any trouble.

Packing people off to monasteries does not, for the record, seem to work as a method for getting them not to make trouble.

And so that boy grew into a monk known to history by his monastic name, Kugyou (his birth name, Minamoto no Yoshinari, is far less commonly used). In 1219, Kugyou took it upon himself to avenge his brother, father, and maternal family by killing his own uncle Sanetomo.

Shortly thereafter, he was apprehended and executed himself.

Now: it has looooong been suspected there was some foul play at hand here–that Kugyou was pushed to remove Sanetomo by one or another member of the Hojo family, who had found this boy too insufficiently pliable.

In particular, it’s sometimes suspected that Hojo Yoshitoki, Masako’s brother, was behind the whole thing–he was supposed to be with Sanetomo when the assassination happened, but begged off due to illness at the last minute. But then again, his motives are also unclear–and Kugyou also killed Sanetomo’s bodyguard, whom he believed was Yoshitoki.

Honestly, we can’t really be sure either way, but now once again we have a problem–and this time, there’s no easy fix. Thanks to Yoritomo killing off his own half brother decades ago, and Sanetomo’s relative youth–he had no children yet–we now both need a new shogun and are out of direct patrilineal descendants of the Seiwa Minamoto line.

So, we’re right back where we started, and with no easy fix to boot, because we have just flat run out of easy choices for replacement shogun.

Now, the Kamakura shogunate will endure past this point, and there are a few different reasons for why that we can point to–the collective interest of the eastern warrior families in preserving it, or prominent civil officials who had relocated from Kyoto to Kamakura to serve the shogunate and had an interest in protecting it, for example–there’s one figure who I think deserves the lion’s share of the credit.

She is Hojo Masako, who at this point is the only person who has been consistently in power from the start of the Genpei War in 1180 up until now. The eldest of her father’s 15 children, she was clearly a deeply shrewd political figure–the Azuma Kagami relates that she helped rally the clans of the east to support Yoritomo in the first place, and of course she worked with her brother to remove her own father from office when he became a threat to her position.

And when, after Sanetomo’s death, the Kamakura shogunate was in crisis, she was the one who guided it through. Over the intervening decades, a new powerholder had emerged in Kyoto while the shogunate was sorting itself out. This was Go-Toba, whom Yoritomo had arranged to take the imperial throne after the seizure of Kyoto from the Taira-backed Emperor Antoku. Like his predecessors before him, Go-Toba had reigned for a time before abdicating and, as retired emperor, setting about trying to rebuild the independent power of the imperial house that had been stripped away by Taira no Kiyomori. Naturally, he was not hugely fond of how much power the Minamoto had aggregated to themselves, and when Sanetomo died he saw a chance to weaken the shogunate as an institution. He used his influence in Kyoto to block the appointment of a new shogun–the job technically needed to be granted by the emperor–and began plotting a rebellion against the nascent warrior government, which began in 1221.

It was Masako who, while there was no shogun, held the warrior families together–after all, her closeness to Yoritomo and her own intelligence meant they all respected her. It was Masako who, when word of Go-Toba’s attempt to seize back power reached Kamakura, rallied the warrior clans against him to defend the shogunate and convinced fence sitters who were debating jumping over to the retired emperor’s side to stick by their side.

She was thus a central figure in the defeat of Go-Toba’s rebellion (known as the Jokyu Rebellion after the era name of the time) and the exile of the troublemaking retired emperor and his allies from Kyoto, to be replaced with more pliably pro-Hojo choices.

There was no shogun from 1219 to 1226–but in the interim, I think it’s fair to say that Hojo Masako filled the role in everything but name. And I’m not the only one; after her husband’s death, she had taken the vows of a Buddhist nun, and one of the nicknames for her is “ama shogun”–the nun shogun.

Masako would die in 1225, and the very next year a more pliant replacement emperor would name a new shogun. However, that shogun could not be from the Hojo line–the title had to go to someone with an appropriately high aristocratic background at court, and while the Minamoto family did have that by virtue of their distant imperial ancestry, the Hojo were provincial warriors and manifestly did not.

But that was ok–the system that the Hojo family, led by Masako’s nephew Yasutoki at this point, came up with had a fix in mind for the issue.

From this point to the end of the Kamakura shogunate, the position of shogun would rotate through a series of aristocrats appointed from Kyoto–members of one or another Fujiwara branch, or imperial princes. Most were children–the first of these shoguns, from a branch of the Fujiwara, was seven years old when he took the title.

These shoguns, however, were mere puppets–the vast majority were children, and they had no real power. Instead, governance was the job of a regent for the shogun–a shikken, in Japanese–who would always come from the Hojo family.

The whole arrangement is very similar to the system used by the Northern Fujiwara in the 900s, with puppet emperors ruled by their own regents.

Thus, the shogun himself was a figurehead; in reality, the Hojo clan called the shots. This was the version of the Kamakura government that would endure for the next century–Japan’s first stable warrior government.

Now, not to belabor this point too much, but I do really want to emphasize that this warrior government–though it is fair, I’d say, to characterize it as the most powerful political force of its time–did not dominate politics completely. The Kyoto court continued to operate, as did the civilian government of the provinces that had existed going back to the Taika Reforms half a millennium earlier.

In a certain sense, the parallel government structure of the era did work. The structure of the Kamakura shogunate is complicated and it’s not entirely clear what some aspects of the bureaucracy were even for, but broadly its main concerns seem to have been adjudicating disputes between or involving samurai families and protecting their legal claims to property–particularly valuable estate lands. That function didn’t necessarily need to disrupt the ongoing Kyoto-based civilian government.

But at the same time, speaking broadly, whenever civilian and military interests butted heads the latter generally did come out on top, be it in military conflicts like the Jokyu Rebellion or in more minor legal disputes.

This parallel government structure can, as I think we’re starting to see, be a bit confusing–we’re going to be dealing with it for a few more episodes yet, though, so it’s worth trying to wrap our heads around.

Fortunately, next week we’re moving over to something a bit different for a time–the massive changes sweeping the religious landscape during the dawn of medieval Japan.