This week, we’re covering the beginnings of the rise of the samurai class by looking at the wars of the 1000s, as well as the Hogen and Heiji conflicts which secured the role of the military class in national politics.

Sources

Takeuchi, Rizo. “The Rise of the Warriors” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol II: Heian Japan

Friday, Karl F. “Dawn of the Samurai” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850.

Images

Transcript

As we’ve seen over the past nine episodes, the history of early Japanese politics is defined by the power struggle between the aristocratic clans of Japan and the imperial family–with the former largely coming out on top, and in particular coming to dominate the Japanese state after the death of Emperor Kanmu and his immediate heirs.

The dominance of the aristocrats, led by the powerful Northern line of the Fujiwara family, would not last, however–it would be challenged, and ultimately defeated, by the rise of a new political force in Japan in the warrior class.

Well, not new; as we’ve seen, the roots of what came to be known as the samurai class go back to the late 700s, so two centuries before the real start of warrior disruption of politics. And by the 900s, the power of independent warrior families was growing to the point that, at least in the provinces, well-connected warriors could threaten the smooth and stable functioning of government.

Still, what all this meant in practice was that powerful warriors were now one more interest group among many jockeying for influence over the government. They were powerful, yes, but they had to compete with the major aristocratic families, with wealthy religious institutions, with provincial governors and local landholders and even the occasional uppity member of the imperial family trying to claw back some semblance of control and power.

And besides, it wasn’t as if the warrior class represented any sort of politically unified front. Warriors were united by ties of political and familial alliance, or more prosaically by financial or economic allegiances. Competition between rival blocs of warriors–who were, after all, aiming to control similar sources of power–was often far fiercer than warrior competition with other interest groups.

For example, there are a pair of wars in the mid-1000s–the former Nine Years War and latter Three Years War–that are often pointed to as showing the emerging (and destabilizing) power of the warrior class in politics, presaging the conflicts of the next century.

And certainly it is true these conflicts were destabilizing politically, but it’s worth noting that they were conflicts between warrior families fighting over economic prerogatives.

Specifically, the conflict emerged over disputes in remote Mutsu Province (a massive area now spread across Akita, Fukushima, Miyagi, Iwate, and Aomori prefectures on the northern end of Honshu). That province was part of the territory conquered from the aboriginal Emishi peoples over the course of the 800s, and even in the mid 1000s there was still a large and culturally distinct Emishi population in the area.

Because of this large and potentially hostile population, the Kyoto court had decided to appoint a clan of aristocrats turned warriors–the Abe family, descended from a distant branch of the imperial family–to serve as military administrators of the area. They would operate alongside the provincial governor, coordinating the local warrior population to keep things under control.

Of course, the Abe and said appointed governors did not always see eye to eye, and in the ensuing political clashes the Abe more often than not came out on top–after all, if nothing else provincial governors had limited terms of office after which they rotated out and were replaced, where the Abe stuck around and were able to build up a substantial and independent base of allies and dependants in Mutsu.

By 1050, the current head of the Abe clan, Abe no Yoritoki, had developed such a strong independent power base that he began largely ignoring the directives of the central government, doing things like collecting taxes in his own name (a job normally reserved for the governor). When a new provincial governor (a distant Fujiwara relative) was appointed for Mutsu and started trying to order Yoritoki to, you know, not do that, Yoritoki responded by mobilizing his followers and attacking the governor’s headquarters.

Now, Yoritoki was probably hoping to force some sort of settlement out of the Fujiwara–after all, who would bother fighting over a remote place like Mutsu–but if that was the hope, well, things didn’t really pan out that way.

The Northern Fujiwara clan had been cultivating its own alliance with a powerful warrior family, the Seiwa Minamoto–one of the groups descended from a former emperor’s extra sons. And so the head of the Seiwa Minamoto clan, Minamoto no Yoriyoshi, was appointed both the new provincial governor and Chinfu Shogun, commander of all military forces in the north of the country, and told to bring Abe no Yoritoki to heel.

However, before long Yoritoki was able to negotiate an amnesty with the central government (driven by the illness of a member of the imperial family, Empress Shoshi–Yoritoki and his supporters were supposed as a part of the deal to pray for her recovery, and I guess it worked because she did and would live for two more decades).

However, in 1056 the ceasefire broke down, right as Minamoto no Yoriyoshi’s time as Mutsu provincial governor was coming to an end. The inciting incident was a nightime raid on Yoriyoshi’s camp by unknown forces–Yoriyoshi accused the Abe clan, and in particular Abe no Yoritoki’s son Sadato, of being behind the attack and demanded they be handed over to him. When Yoritoki refused, Yoriyoshi mobilized his forces and wrote Kyoto for an order to punish the Abe (which he did get).

This time the fighting did not end in short order–it would continue until 1063. Initially the Abe held the upper hand, defeating the Minamoto forces and nearly crushing them until a rebellion by an Abe clan relative forced Yoritoki to split his attention (and eventually, the rebels succeeded in killing him). But even divided, it took years for the Minamoto to finish off the Abe clan.

Still, the war succeeded in making the reputation of the Minamoto as fierce warriors, in particular Yoriyoshi and his son and heir Yoriie (who had been 15 when the fighting started and essentially grew up at war in Mutsu).

The Former Nine Years War was a comparatively large conflict, but in its basic organization not unusual–and again, not necessarily a direct threat to the rule of the Kyoto government, since it was in the end an internal dispute between warrior families.

Ditto the related Latter Three Years’ War, which we’re not even going to go into much detail about–basically, this was a similar conflict once again in Mutsu, between Minamoto no Yoriie (who was appointed provincial governor in the 1080s) and another local warrior clan named the Kiyohara. The Kiyohara had come into Mutsu to help put down the Abe clan in the 1050s, but had since fragmented into three competing lineages fighting an internal family civil war. Yoriie intervened to bring the three to heel.

Here too, the issue at hand was a private dispute between warriors–indeed, that was the interpretation of the central government, which successfully placed Yoriie under house arrest after the war ended on the grounds that he had pursued a private vendetta against the Kiyohara that was outside the bounds of his mandate as governor.

What really lay the groundwork for the upending of the Heian system was not the power of the warrior clans in and of itself but a shifting balance of power in Kyoto, which created a power vacuum at the center.

From the time of Fujiwara no Yoshifusa (who we talked about back in episode 507), the Northern branch of the Fujiwara clan had dominated politics through two means: political marriages into the imperial family (ensuring future heirs were at least part Fujiwara) and monopolization of the two posts of imperial regent (sesshou for child emperors, kanpaku for adult ones).

This system, alongside two other longstanding political rules–a requirement that the Dajokan, or council of state, draft the language of imperial edicts rather than the emperor, and that the emperor observe debates of state ministers behind a curtain and without participating–limited the direct ability of the emperors to intervene in politics. This in turn, alongside manipulation of the succession and the provision of Fujiwara concubines to the emperors, allowed the Fujiwara to dominate the imperial court from the 850s well into the early 1000s.

However, during the 1000s a new locus of power began to emerge at the imperial court to challenge the Fujiwara regents: the in, or retired emperor.

Being emperor, you see, is kind of an exhausting job. By the Heian era the emperors were not involved that much in actual administration (and were even further removed from those roles as time went on), and were concerned far more with ritual and cultural activities. Luckily for them, however, they did not have to endure very long; a combination of concerns about the return to the bloody succession wars of the Nara years and earlier, and a desire on the part of the Fujiwara regents to keep younger, Fujiwara- descended and theoretically pliable emperors on the throne led to a change in how imperial rules played out.

Emperors were now encouraged to abdicate and hand over power to their chosen successors, keeping the lines of succession uncomplicated (important given the number of imperial princes floating about) and generally serving as a preventative against older emperors more likely to chafe against Fujiwara rule coming to power.

Once an emperor abdicated, they became an in, a retired sovereign. The Ritsuryo system actually didn’t have a legal provision for the status of a retired emperor, but in practice they retained much of the prestige associated with their former position–and, as older men in the imperial line, served as de facto heads of household for the imperial family itself.

In addition, they were often rewarded with lands and independent sources of wealth in recognition of their former status.

All of which meant that in practice, the in became one more faction vying for power in the Heian system–joining a factional struggle between the Fujiwara, the other aristocratic houses, the warriors, the provincial governors, local landlords, and religious institutions.

That factionalism, in turn, was put into overdrive by the fact that each of these groups could increasingly rely on extragovernmental sources of power–chiefly shoen landholdings providing them substantial independent wealth.

What eventually emerged was a sort of bizarre dual regency, with both the retired emperors and the dominant Northern Fujiwara battling for influence over the emperors.

Initially, the Fujiwara were not looking like they’d relinquish their hold any time soon, but amazingly, right at the apogee of Fujiwara power, things fell apart.

That apogee came under Fujiwara no Yorimichi, who served a regent for an astonishing 51 years across the reigns of three different emperors, from 1017 to 1068. Yorimichi’s incredibly long tenure in office allowed him to fill up the ooku, or inner palace of the emperors, with loads of Fujiwara clan daughters (most prominently three of his own), but in one of those random twists of fate none of those daughters had a son.

Years of Chinese influence had made the old solution of going to a female sovereign a non-starter, and so Yorimichi was forced in 1068 to allow the ascension of an emperor who was both an adult and not at all a Fujiwara relative–Emperor Go-Sanjo.

Go-Sanjo’s health was not the best, and tenure in office was not the most impressive in terms of results; he was the one who, as we discussed last week, attempted with no real success to reign in the spread of the shoen system. However, his desire to claw more power back to the imperial family did have one important result: he appointed his own heir, once again a non-Fujiwara, who took the throne as Emperor Shirakawa in 1072 a year before Go-Sanjo died.

In his essay on the politics of Heian Japan, Mikhael Adolphson calls Shirakawa the most talented emperor politically since the reign of Kanmu more than 200 years earlier, and frankly he’s pretty spot on. Shirakawa would remain on the throne for 14 years, from the time he was 19 to the age of 33 by the Western count, before abdicating–following Go-Sanjo’s lead in using the chance to abdicate in order to pick a non-Fujiwara heir.

As the retired emperor, he then oversaw the politics of the imperial family for the next several decades until his death in 1129, helped along by the fact that the Northern Fujiwara were a bit leaderless when two of their family heads died unexpectedly in 1099 and 1101. Shirakawa took advantage of the chaos to, in essence, copy the political tactics the Northern Fujiwara had once used.

First of course was control of the succession; as retired emperor, Shirakawa oversaw a line of anti-Fujiwara emperors descended directly from him (Emperors Horikawa, Toba, and Sutoku–his son, grandson, and great-grandson). Thus, he ensured the Fujiwara could not directly control the throne by appointing a pliant young relative.

Second, he continued his predecessor’s policies around reigning in shoen, but significantly he also took the unprecedented step of getting the imperial family shoen of its own–usually in the name of one of the many imperial princes, since theoretically the emperors themselves could not hold land. These tax-free shoen estates became a completely independent basis of economic power for the imperial family.

Next, Shirakawa began to set up imperially-controlled religious institutions and dispatch imperial relatives to serve as priests and abbotts at influential temples and shrines–essentially, battling the Fujiwara for control of major religious institutions and rituals and the legitimacy these could bring.

Finally, Shirakawa began to cut deals with warrior families; just as the Fujiwara had, in particular, developed a close alliance with the Seiwa Minamoto, Shirakawa cultivated an alliance with another powerful warrior family, the Kanmu branch of the Taira clan.

Shirakawa also cultivated warriors loyal solely to him, essentially buying followers by provisioning them with estates of their own.

As a result, by the time Shirakawa died in 1129, the imperial house was, in many ways, a totally independent political power in its own right.

The modern day historian Kuroda Toshio described the political order that emerged from this as a sort of co-rulership model where power was shared between various kenmon–a term that originally meant “noble houses”, but which came to mean any of the major powerholders of the late Heian period.

Kuroda identified these kenmon as having five basic things in common. First, they had a distinctive institutional or family headquarters independent from the Kyoto government, and second, that headquarters was ruled by an independent head of household whose job was not the result of government office but of family or institutional inheritance. Thus, their authority was not legally derived from the government. Third, said leader had an independent base of followers pledged personally to him. Fourth, the kenmon were self-ruling, having their own systems for promoting or demoting followers or adjudicating internal disputes without government interference. And fifth, the kenmon held independent bases of economic power, usually shoen–over which their authority was also legally absolute, as government agents could not, say, enter a Fujiwara shoen without Fujiwara permission.

This definition certainly fit the Northern Fujiwara, and to a lesser extent other aristocratic families or lesser Fujiwara offshoots. Thanks to Shirakawa, it fit the imperial family as well–and it fit powerful religious institutions like the Tendai sect temple of Enryakuji atop Mt. Hiei or the powerful temples of Nara, which had successfully used their influence to lobby for powers of their own. And by the 1100s, it increasingly fit the warrior families, and especially major ones like the Seiwa Minamoto and Kanmu Taira.

Read through this lens, what enabled the rise of the samurai to political prominence was the “kenmonization”–or in other words, the fragmentation of political power into these independent power bases–creating an unstable political situation into which samurai families could then insert themselves.

Of course, that’s a rather dry way of framing things, even if it is accurate to the balance of power. Viewed from a less abstract position, the reality is substantially bloodier.

In particular, the rise of the samurai to political power is often tied to three distinct conflicts: The Hogen and Heiji Rebellions, followed by the Genpei War. The rest of this episode is going to be about detailing the first two conflicts; we’ll pick up with the third at the start of next week.

So first, the Hogen rebellion–named, of course, via the nengo era name system, as the year of the rebellion (1156) was also the first year of the Hogen era.

The Hogen Rebellion grew out of the death of a man who had come over the course of his lifetime to dominate the politics of the Kyoto court: Emperor Toba, the Grandson of Shirakawa and retired emperor.

You see, as successful as the retired emperors were in bolstering the power of the imperial family particularly in comparison to the Fujiwara regents, that success did not come without cost. There was always a bit of resentment of the seniormost retired emperors acting as patriarchs of the imperial clan–first by the reigning emperors, who after all were supposed to be masters of the proverbial house but who now had to take orders from their elders, and then among the younger retired emperors who were excluded from the power of the senior retired emperors.

Shirakawa had generally been able to balance these competing political prerogatives and keep folks within the imperial family generally working together. Toba, however, was far less able at this particular task, and in particular managed to foster two substantial rivalries within powerful families that blew up after his death.

First was a division within the imperial household between the retired emperor Sutoku and the reigning emperor at the time of Toba’s death, Go-Shirakawa. Sutoku was legally the eldest son of Toba, but for whatever reason the two never got on–the theory that flew around the capital was that in fact, Toba’s father Shirakawa had slept with one of

Toba’s wives out of wedlock and Sutoku was the product of that union.

Which yeah, I guess that’d make for a complicated familial relationship if your “son” was actually your own father’s lovechild.

Regardless of whether that’s true, Sutoku was forced to abdicate in 1141 in favor of one of Toba’s other sons, Emperor Konoe. He apparently resented this move quite a bit. As a junior retired emperor, Sutoku pinned his political hopes on Konoe naming one of Sutoku’s sons as his heir (since Konoe had none of his own), but when Konoe unexpectedly died in 1155 without naming an heir Toba again stepped in to name another of his own sons (Emperor Go-Shirakawa) and position Go-Shirakawa’s own son as heir.

This pissed Sutoku off mightily, and that resentment would come to the surface after Toba’s death.

The second familial split that the retired emperor Toba exacerbated was actually within the Northern Fujiwara. Toba’s grandfather Shirakawa had manufactured a pretext to exile the head of the Northern Fujiwara, Fujiwara no Tadazane, from Kyoto–obviously intending to weaken the Northern Fujiwara politically by forcing their leader from the center of power. Toba, however, recalled Tadazane from exile, hoping to form a political alliance with him. This worked for a time, but Tadazane also busily set about trying to rebuild the weakened fortunes of the Northern Fujiwara.

He also was apparently not pleased with how things had been handled in his absence; while he’d been away, his eldest son Tadamichi had been handling Northern Fujiwara affairs in the capital, but Tadazane set about trying to oust Tadamichi in favor of his own favored younger son Fujiwara no Yorinaga.

I guess Toba and Fujiwara no Tadazane got on because of how much they disliked their own eldest sons.

Tadazane’s attempt to oust his eldest in favor of his youngest did not work, however. You see, when emperor Konoe died suddenly in 1155 of an illness, rumors began to fly around Kyoto that he’d been poisoned or hexed in some way, and that Tadazane’s favored son Yorinaga had been behind it. It’s unclear how true the rumors were or whether they were pure political opportunism–regardless, Yorinaga was excluded from politics by virtue of the slander, but the division between pro-Yorinaga and pro-Tadamichi factions within the Northern Fujiwara remained.

And when Toba died, that resentment blew up. Sutoku and and Yorinaga decided to work together to try and oust Toba’s chosen emperor and take control of the government for themselves–working together to sort out their familial conflict the old fashioned way, with violence.

Both sides, of course, had clients and allies they could call on to support them–including growing numbers of warrior families. In particular, of course, the retired emperors by this point had a close alliance with the Kanmu Taira, while the Northern Fujiwara regents had spent over a century cultivating an alliance with the Seiwa Minamoto.

But in this particular fight, both sides claimed to represent the interests of the imperial family and the Northern Fujiwara–so where would the warrior families come down?

In point of fact, they were split, and along generational lines too. The family head of the Seiwa Minamoto, Minamoto no Tameyoshi, backed the rebelling Sutoku and Yorinaga, as did the younger brother of the Kanmu Taira leader Taira no Tadamasa (the Taira family head, Taira no Tadamori, was off fighting pirates in the inland sea).

However, Tadamori’s son Kiyomori backed the reigning emperor Go-Shirakawa, as did Minamoto no Tameyoshi’s son Minamoto no Yoshitomo. And in this case, the young guns proved the ones to beat. When it became clear things would come to blows, both sides gathered armies of a few hundred in the early summer of 1156. They then vaccilated about what to do next; apparently, it was Minamoto no Yoshitomo who suggested a surprise night attack against the forces of the rebelling Sutoku and Yorinaga, hoping to win swiftly and decisively.

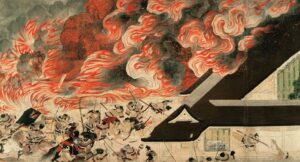

And this, in the end, was the right move; Yoshitomo and Taira no Kiyomori led a night attack that crushed the rebellion in the span of a day.

Though the Hogen Rebellion itself was over in the span of a single night, it still marked a big departure from past political eras. Previous succession disputes among powerful families would have been resolved via political maneuvering, manipulation, and maybe a couple of exiles to spice things up–but now, recourse to military force was easy, and violence has a way of handling issues in a rather permanent way.

And with the precedent set that this was an option, Emperor Go-Shirakawa was not interested in walking things back. Indeed, he took the rather unprecedented step–urged on by one of his close advisors Fujiwara no Michinori (better known by his lay Buddhist monastic name, Shinzei)–of finishing off the rebel cause by ordering the first executions in over 350 years, since the execution of one of the Fujiwara coup plotters who had been looking to restore a previous emperor (Emperor Heizei) back to the throne.

We talked about this back in episode 506. In the intervening centuries, it had become more common to commute death penalty sentences to long-term exile–but Go-Shirakawa was convinced it was time to set an example.

Fujiwara no Yorinaga was killed in the fighting; the retired emperor Sutoku was captured, having fled to Ninnaji, but his imperial ancestry protected him and he was merely exiled to a remote part of Shikoku. However, 17 of Sutoku and Yorinaga’s allies, including both Minamoto no Yoshitomo’s father Tameyoshi and Taira no Kiyomori’s uncle Tadamasa, were executed–indeed, the Minamoto and Taira scions were given the order to do in their own relatives themselves.

And despite both following those orders and essentially winning the whole damn thing for Go-Shirakawa in the first place, the rewards for the victorious warriors were rather meager; Kiyomori received a provincial governorship in Harima Province, and Yoshitomo, who had come up with the winning battle plan in the first place, received an appointment with in the imperial military bureaucracy (Provisional Head of the Left Horse Guards, a mid-ranking position that probably had no power or stipend attached).

The outcome of the Hogen Rebellion was to establish Emperor Go-Shirakawa as the main political force in Kyoto; in 1158, he would abdicate, but continued (naturally) to dominate things behind the scenes as retired emperor.

However, Go-Shirakawa’s victory still left a lot of uncertainty floating in the air–particularly because the retired emperor could not, of course, rule entirely by himself. In particular, two main camps began to emerge around the new master of Kyoto once he solidified his hold on the city. The first was around Shinzei, who had become close with Go-

Shirakawa because his wife had been the retired emperor’s wet nurse.

This allowed Shinzei–who was a Southern Fujiwara, and thus probably would not have risen to the pinnacles of power in a more normal political climate–to become one of Go-Shirakawa’s closest confidants, able to freely give advice like “let’s go against over 3 centuries of precedent and start executing people.”

However, shortly after the Hogen Rebellion a new figure began to rise at court–Fujiwara no Nobuyori, from the rival Northern Fujiwara family of imperial regents. For reasons that are a bit unclear, Nobuyori and Go-Shirakawa became increasingly friendly during these years, to the point that Nobuyori became a serious threat to Shinzei’s political power.

Shinzei and Nobuyori became locked in a contest for influence over Go-Shirakawa, and the retired emperor’s other followers began to gravitate into one of their two orbits as a result. In particular, Taira no Kiyomori sided with Shinzei, while Minamoto no Yoshitomo sided with Fujiwara no Nobuyori.

And eventually, Shinzei started to come out on top; in particular, in 1159, he was able to block the advancement of Nobuyori to a bureaucratic office (basically a posting in the imperial palace guard) that was usually a prerequisite for increased court rank. This so incensed Nobuyori that he actually refused to attend court at all for a time, excusing himself on the grounds that he needed to “practice the military arts.”

Which is not ominous at all, no sir, especially not since the precedent is now established that if you don’t like the political situation there’s probably a warrior out there willing to chop off some heads until you do!

Which brings us to roughly January, 1960, corresponding to the tail end of the first year of a newly-named era (Heiji). In that month, Taira no Kiyomori announced a plan to go on pilgrimage to Kumano, a region on the west coast of the Ise Bay in what’s now the southern coast of Mie prefecture. That area is home to many ancient and venerable shrines; more importantly for us, the pilgrimage route there and back was 175 miles (or about 282 kilometers), and once you were there the mountainous pilgrimage route between all the shrines took five days or so to traverse.

Which meant that for about a month Shinzei would be without his greatest military supporter in the capital, and well, I’m sure you can do the math from here.

And so, just five days after Kiyomori left town, Fujiwara no Nobuyori began to move against Shinzei–joined by Minamoto no Yoshitomo, whose own fortunes had been frustrated by Shinzei’s blocking the rise of his patron Nobuyori. They were joined by another faction of warriors who had no problem with Shinzei per-se, but who were loyalists to the sitting emperor Nijo rather than the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa.

Together, they attacked Shinzei’s residence and the neighboring Sanjo palace where Go-Shirakawa was residing, swiftly capturing both the sitting and retired emperor. Shinzei was able to briefly escape to Nara, but was tracked down and executed after he attempted but failed to commit suicide. His severed head was brought back to Kyoto and put on display like that of a common criminal.

Nobuyori, meanwhile, exercised his control over the emperor to purge Shinzei’s supporters from office (including Kiyomori), and to promote both himself and Minamoto no Yoshitomo (giving Yoshitomo many of the positions that had been stripped from Kiyomori).

Taira no Kiyomori was, again, away from the capital during all of this–by the time he got wind of what had happened, he was near the tip of the Kii peninsula, almost a week’s ride from Kyoto. After some back and forth about what to do, Kiyomori decided to ride for the capital–gathering more of his followers to him along the way, so that he arrived with an entourage of over 300 men. Initially, Kiyomori seemed to accept defeat, showing his willingness to follow the decisions of the new regime–but then, things flipped on their head.

Emperor Nijo had grown increasingly disillusioned with Fujiwara no Nobuyori in particular–his followers had joined Nobuyori and Yoshitomo’s uprising out of a belief that Emperor Nijo’s political hand would be strengthened by it, but instead Nijo simply started giving the emperor orders himself. And so en masse they defected to Kiyomori; Nijo supposedly snuck out of the imperial palace to Taira no Kiyomori’s villa at Rokuhara by disguising himself as a woman to escape detection.

That very same day, the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa and his followers did the same thing for very similar reasons, deserting Nobuyori and fleeing to Kiyomori.

Obviously, this flipped the military balance of power, but more importantly the presence of both leaders within the imperial line gave Kiyomori legitimacy; he could brand himself as defending the imperial cause, and his opponents as rebels against the throne.

And you can probably guess how things unfolded from here.

Once again, the actual fighting lasted only a single day; Kiyomori launched an all out assault the day after Nijo and Go-Shirakawa came to him, and though the opposition held out for a time, Kiyomori was then able to break their defenses by an ingenious strategy. He ordered his men to fall back after their initial assault on fortified positions around the imperial palace; when Nobuyori and Yoshitomo’s forces emerged to chase them down, a second Taira detachment slipped in behind them to seize the emptied fortifications, trapping the Nobuyori/Yoshitomo forces without a line of retreat. Kiyomori then baited them into an attack on his Rokuhara palace, where the opposition was crushed in a matter of hours.

Fujiwara no Nobuyori, fleeing in advance of the final battle, was caught near Rokuhara itself and executed alongside the banks of the Kamo River. He was only 26.

Minamoto no Yoshitomo attempted to flee east, towards the lands held by the Minamoto, where he could presumably lick his wounds and maybe cut some sort of amnesty deal.

However, one of his retainers betrayed him along the way; he was captured in Owari Province (modern Aichi) and executed.

His two eldest sons were killed as well; the third and youngest was spared only because of the intercession of Kiyomori’s stepmother Ike no Zenni. Why exactly she interceded is unclear; the Heiji Monogatari, a dramatized tale describing the events of this conflict, says it’s because the young boy was the spitting image of one of her own sons. Others have theorized she had been convinced to step in by Seiwa Minamoto family relatives hoping to salvage something of the situation.

We simply do not know. All we do know is that Kiyomori gave in and sent the boy–Minamoto no Yoritomo– east instead of killing him, entrusting him to a Taira clan ally named Hojo Tokimasa.

His younger half brother, Yoshitsune, would similarly be allowed to live–but was sent to the Tendai sect temple of Kuramadera outside Kyoto to be raised as a (hopefully apolitical) monk.

And I’m sure there’s no way that’ll come back around to bite anyone in the behind.

The Hogen and Heiji Rebellions had their origins in infighting between the two parts of the imperial line, but more crucially for us they revealed how strong the political power of the warriors had become–now it was they who could decisively tip the balance one way or another in Kyoto. And next week, we’ll see the warriors not tip that balance but radically upend it.