This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: The US Occupation of Japan after World War II represented a truly massive undertaking. American military and civilian personnel spent just over a decade rebuilding Japan’s government, economy, and society from the ground up. What did that look like in practice, and how does the legacy of the Occupation era remain with Japan today?

Sources

Dower, John. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan

Fukui, Haruhiro, “Postwar Politics, 1945-73” and Yutaka Kosai, “The Postwar Japanese Economy, 1945-1973” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol VI: The Twentieth Century

Images

Transcript

So, we left off last time with the advent of the Pacific War–the destructive conflict between Japan and the Allies, most prominently the United States.

And just to be up front, I do not plan to devote really any time in this series to a discussion of that conflict in depth, for a few reasons. First, it’s one of the most talked about conflicts out there, so if you’re interested in the Pacific War I don’t think it’ll be hard to find much material.

Second, there are a lot of famous events of this conflict to cover, and there’s no way I could get to them all while keeping to my outline for this miniseries. Plus, I’ve touched on quite a few already which you can find in the back archive.

In particular, I do personally think that the six episode series on the atomic bomb starting with episode 108 is one of the best things I’ve ever done in terms of research, though the older stuff does have some rough audio quality.

What can I say? Academia doesn’t do a great job preparing you for sound editing

Finally, and this might seem a bit paradoxical given what I’ve just said, but in a certain sense there’s not a whole lot to talk about. Japan’s plan to win the war against America was to try and land a single devastating blow that would take the US out of the war quickly and result in a negotiated peace favoring Japan.

Instead, the Pearl Harbor strike enraged Americans but was not successful in annihilating the US Pacific Fleet; in particular, its three aircraft carriers (Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga) were all away from the base at the time.

In fact, I would argue that within about half a year of Pearl Harbor it was Japan that had decisively lost the war when a good chunk of the Imperial Japanese Navy was wiped out at Miday (including four of its own aircraft carriers and some of its most experienced crews). From that point on, the plan of trying to set up a defensive perimeter to ward away American counterattacks until they came to the table was no longer viable–America had a decisive edge at sea, and it was only going to get more decisive as time went on.

Realistically, from this point onward the original plan to win the war was not workable, but Japanese leaders were not willing to admit this–particularly once in 1943 the Allies declared their goal to be unconditional surrender, so no negotiations that would allow Japan to hang on to part of its wartime gains.

Instead, they clung to increasingly absurd notions about doing just enough damage to the American will to fight that the US would come to the table and they could hang on to something. Any day now it would happen, of course–the Americans were decadent, spiritually weak liberals, so how could it not? Chasing that absurd notion in order to avoid confronting their own failure kept Japan in the war until August, 1945, and killed millions of Americans, Chinese, and Japanese people as a result.

On August 15, 1945, the war finally did end, with the Showa Emperor–known in the West more commonly by his personal name, Hirohito–reading out an Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War that never once used the word surrender and instead noted in somewhat darkly comical language that, “the war has not necessarily developed to Japan’s advantage.”

A few weeks later, on September 2, the American battleship Missouri entered Tokyo Bay for the signing of a formal surrender. As Japanese government officials boarded the USS Missouri to sign the instrument of surrender, they were greeted to a small visual spectacle that had been the brainchild of General Douglass MacArthur. MacArthur arranged for the 31-star American flag that had flown on the Susquehanna during the Perry Expedition–and which Perry had bequeathed to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis–to be brought to Asia, and hung it in a portrait frame on the main deck of the ship. In his speech on the occasion of the surrender, MacArthur described Perry as aiming to “bring to Japan an era of enlightenment and progress by lifting the veil of isolation to the friendship, trade, and commerce of the world.” What the Japanese statesmen listening to the speech thought of that remark remains unrecorded.

Regardless–the war was now over, and in its aftermath a new order quickly emerged. Allied planners had been working on a vision for postwar Japan for several years by this point, and so the very day of the surrender the plan went into motion.

That plan, broadly, was for the Allies to occupy Japan. Unlike Germany, which was split into four occupation zones–American, French, British, and Soviet–here there would be no divided occupation. Stalin did attempt to convince the Americans that his cooperation in the final days of the war–he had declared war on Japan the same day as the Nagasaki bomb was dropped–meant the USSR deserved a small section of the Occupation for itself, but the Americans would never hear it. Stalin had to content himself with control of Manchuria and the Northern part of Korea, as well as the retaking of southern Sakhalin lost by the czar and the claiming of the Kuril islands ceded in the Meiji years.

But in Japan proper, the Americans called the shots, with their leader being the very same General Douglass MacArthur who had directed the surrender ceremony on Sept 2. MacArthur was picked for a few different reasons; first, he was one of the two most prestigious military commanders of the Pacific Theater, rivaled only by Admiral Chester Nimitz. Second, he was a Republican, and the Democratic administration of the new President Harry Truman wanted to prove its bipartisan bonafides. Third, MacArthur had been an administrator of the US colonial regime in the Philippines back in the 1930s, and the thinking was this gave him both administrative experience (fair enough) and “experience working in Asia” (rather problematic given that Japan is not the Philippines, and that at any rate in time honored colonial tradition MacArthur spent most of his time with other Americans in their high end neighborhoods than with the locals).

Regardless; MacArthur was in charge, given the title of Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan. The government he formed under him used that same title–SCAP–and would run the country for more than half a decade.

SCAP consisted of thousands of civilian and military personnel who essentially set up a new ruling bureaucracy controlling Japan. Most of the high level people were old-time MacArthur loyalists, many of whom had been on his staff since his days in the Philippines back in the 1930s. And indeed, despite the fact that ostensibly SCAP was accountable to a Far Eastern Commission back in Washington DC and an Allied Council in Tokyo where the other powers were represented, practically it was MacArthur’s show. The general would not brook outside interference in what he saw as his responsibility.

Meanwhile, the lower levels were filled by a wide range of people, including a specialist in labor organizing, a German judge with background in the Japanese legal system, a Jewish-American Austrian refugee who spoke Japanese fluently, and others.

Notably absent from this group were many Americans with a pre-war background in Japan, who were perceived as too tied to the old way of doing things–too sympathetic to the Meiji system to oversee its reconstruction.

What were the goals of this motley collection? They were spelled out in a Post-Surrender Policy guideline drawn up by the American government, but the goals spelled out there were extremely broad and practically speaking, SCAP had a lot of leeway in how it approached them.

By the way, you might be wondering how SCAP was supposed to implement policy given that it was overseen by Americans, not exactly known for our familiarity with foreign languages in general or Japanese in particular (not to mention MacArthur and his closest supporters were military men, not politicians or bureaucrats). The answer is that SCAP simply grafted itself on top of the existing state structure–if you ever saw one of those social pyramids social studies teachers love to use in grade school, just imagine a new layer being smacked onto the top of that. SCAP simply replaced the military and bureaucratic leadership that had previously made decisions–the rest of the governing structure remained intact.

Anyway: Broadly speaking, MacArthur was handed two goals: to demilitarize the country, and to democratize it.

There was a third, implicit goal in there as well: given the already rising tensions of the Cold War, Japan should be rebuilt as an American-aligned bastion. This was not a particularly pressing issue–until 1948-49, when the initial choice for an American ally in Asia, the Republic of China, began to implode in the face of Mao Zedong’s communist party. Once China was off the table, making Japan into the American bulwark in Asia suddenly seemed a lot more important.

This final goal of the Occupation is something we’ll spend more time on a bit later in the episode, but I do want to highlight it early on.

The first year of the Occupation, however, was focused overwhelmingly on dismantling what the American authorities perceived as the foundations of wartime militarism. That meant, first and foremost, the shuttering of both the army and navy and the mass demobilization of soldiers and seamen as quickly as they could be brought home. Indeed, one of the biggest logistical undertakings of the Occupation era was simply evacuating Japanese settlers and military men from the colonies, which took years to complete–and famously, a few tenacious soldiers refused to believe the surrender was real for decades.

It’s also worth noting that the Soviet Union in particular delayed the process–it held large numbers of Japanese prisoners captured in Manchuria and North Korea for years, utilizing them for labor to rebuild the shattered Soviet system before eventually caving to international pressure and returning them home. The Soviets, by the by, were not done taking Sakhalin or the Kurils when Japan surrendered on August 15, and kept their military operations going for several more weeks regardless.

That Stalin guy, it turns out, wasn’t the most trustworthy fellow.

Anyway: military institutions in Japan were shuttered with astonishing rapidity, shutting down the Army and Navy Ministries themselves in November, 1945. That rapidity was of course intended to get military-aligned figures out of government as quickly as possible. It did have a few unfortunate side effects though; the army in particular, for example, had stockpiled a lot of supplies to repel an American invasion, including more traditional fare as well as a massive amount of methamphetamine to keep its soldiers alert. Those drugs were promptly stolen from army supply depots once the army started to shut down, and in particular became a massive source of funding for the revival of the old yakuza in the postwar era.

Also handled rather poorly in all this were the former military men themselves, who remember were all conscripts outside of the officer corps. The end of the military ministries meant no veteran’s supports or pensions to support any of them (including those too injured to work); the sight of former soldiers begging in public spaces was a common one during the postwar years.

Despite all this, abolishing the military was overwhelmingly popular during the Occupation–after all, the common thinking was that the military deserved most of the blame for dragging Japan into an unwinnable war. Which wasn’t unfair, honestly–but then and now there was a tendency to downplay how popular the empire’s wars had been with the masses, at least until they started to lose em.

Less popular was the decision by SCAP to suppress anything that, in the view of its censors, smacked of “prewar militarist ideology”–by which was meant anything that could be viewed as pro-military propaganda.

So, for example, SCAP banned the performance of certain kabuki plays–most notably Chushingura, the dramatized retelling of the 47 Ronin Tale which had been held up by the wartime government as an example of loyalty unto death. It also censored publications it viewed as excessively militarist (while quietly banning other discussions viewed as potentially anti-American, most notably any publication of material related to the atomic bombings). Even martial arts like kendo and judo suffered brief bans, given that they had been part of required courses at military academies.

These were far less popular than the abolition of the military had been (and those bans that weren’t quietly walked back by SCAP were all immediately reversed when the Occupation ended) but it also wasn’t like the average person on the street could do much about it. After all, what could they do about it? SCAP was not subject to any sort of oversight on the Japanese side.

The other, and far more complicated goal of the early Occupation was to democratize Japan–the theory being that a more democratic Japan would never again be a threat to the peace of Asia.

Now, “democratization” was a big task that involved remaking–just to give some examples–the school system from the ground up, decentralizing it and setting up local school boards with more oversight. It involved remaking the Japanese economy so that power was less concentrated in the hands of powerful zaibatsu megacorporations. It meant setting up very strict rules around the government’s ability to influence religious movements or to preference Shinto above other religions.

There’s no way we could do all this justice, and to be honest I want to focus on what I think are the two most important aspects of democratization–the imperial institution, and the constitution.

The question of what to do with Japan’s emperor–Hirohito, or the Showa Emperor, if you want to be more formal–had been a topic of substantial conversation among the Allies throughout the war years. On the one hand, as we’ve seen, Japan’s emperors reigned but did not traditionally rule–it was hard to argue that Hirohito himself had masterminded Japan’s wartime militarism.

On the other hand, he was the head of state and, on paper, the head of government. The young emperor-44 at the time of surrender–had intervened in policy before, for example demanding the punishment of the assassins of Zhang Zuolin in 1929, and of course dramatically interceding at the end of the war to throw his opinion behind surrender. So clearly he had power–and could have done more to reign in the worst wartime behaviors.

There was also the awkward fact that, if one considered the sweep of Japanese aggression across the 30s and 40s, only one person was in a position of authority during that entire time–the emperor. And of course, all of it had been done in his name; how could he not bear some responsibility?

The debates around this question were and remain intense; but fortunately for us they don’t really matter too much here, because in what would be something of a pattern for SCAP only one person’s opinion on the matter really counted, and he made his mind up pretty damn quickly.

That one person was, of course, General Douglass MacArthur himself. Just days after the formal surrender in September, 1945, Hirohito himself came calling on the new SCAP commander–quite a concession in and of itself, given that the emperor did not usually make house calls.

Now, we don’t know quite what happened in this meeting–the only interpreters present were part of the notoriously tight-lipped Imperial Household Ministry (since demoted to a mere agency). MacArthur, however, was apparently deeply impressed by the meeting, referring to Hirohito afterwards as, “the first gentleman of Japan” and saying the emperor had offered to abdicate and take full responsibility for the war.

MacArthur decided more or less then and there that he would protect the emperor–despite calls throughout 1945 and 1946 within Japan that Hirohito abdicate, and in some cases that the imperial institution itself be abolished.

Still, MacArthur was the ultimate decisionmaker, and his loyalists at the top of SCAP enforced his will. Talk of getting rid of the emperor was swiftly slapped down; when former Prime Minister Konoe stated he believed the emperor should abdicate, all that resulted was SCAP officials labeling him as “a rat who was prepared to sell anyone to save himself.”

Brigadeer General Elliott Thorpe, an intelligence expert and one of the people charged with assembling lists of war criminals to be tried, stated openly his agreement with MacArthur on the question of keeping Hirohito on the throne because, “otherwise we would have nothing but chaos. The religion was gone, the government was gone, and he wa the only symbol of control. Now I know he had his hand in the cookie jar, and he wasn’t any innocent little child. But he was of great use to us, and that was the basis on which I recommended to the Old Man [MacArthur] that we keep him.”

MacArthur and his loyalists held steadfastly to this opinion, and for his part while Hirohito appears to have been willing to abdicate to save the imperial household, he wasn’t going to do it if he didn’t have to. One of his closest advisors, Kido Koichi, advised the emperor both in 1945 and again in 1951 at the end of the Occupation to abdicate because otherwise, “the end result will be that the imperial family alone will have failed to take responsibility and an unclear mood will remain which, I fear, might leave an eternal scar.”

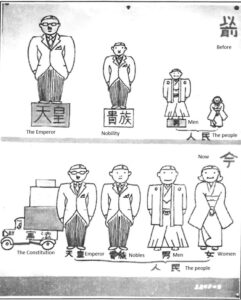

Nothing ever came of it; instead, Hirohito and SCAP embarked on a bold new initiative to remake the emperor’s image. On January 1, 1946, Hirohito gave a new year’s address where, under the direction of SCAP, he proclaimed that, “The ties between Us and Our people have always stood upon mutual trust and affection. They do not depend upon mere legends and myths. They are not predicated on the false conception that the Emperor is divine….”

It’s worth noting that there’s some controversy around this specific wording, because the Japanese text uses a different word (akitsumikami) from the one used in most imperial propaganda going back to the earliest centuries (arahitogami)–and today, right-wing groups maintain the position that the emperor is a descendant of the gods.

Hirohito was also trotted out for a series of national tours intended to build support for the new regime by showing the emperor himself as “democratized”–dressed up in a suit, tie, and tophat, afoot instead of on horseback, and just generally being portrayed as a man of the people. He was even encouraged to shake hands with the common people (something he was never very good at) and to take up some unthreatening hobbies (he settled on marine biology).

There’s a LOT more to say about the remaking of Hirohito’s image–and what we can determine about how the man himself felt about it all. But of course there’s not room to get into it here, but I can direct you to the 6 part series on Hirohito starting with episode 226 if you really want to get into it; episodes 230-231 deal with his postwar life if that’s what you’re interested in.

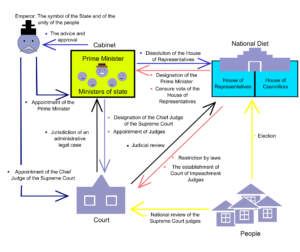

What I want to talk about now is another side of democratization–the Constitution. From the start of the Occupation, revising the Meiji Constitution to make it more democratic had always been a goal–but remarkably, there wasn’t a lot of actual groundwork done to decide what that would look like in practice. Initially, the civilian government of Japan handed the job over to Matsumoto Joji, a specialist in commercial law who assembled a team of experts to draft a new version of a constitution in the fall of 1945.

The resulting draft, however, was deemed unacceptable by MacArthur–it created a modified version of the Meiji system that essentially made the emperor into a more traditional constitutional monarch, but left much of the rest of the system intact.

This was felt to be insufficiently democratic; but here, rather than directing Matsumoto to have another go at it, MacArthur decided on a different route.

He directed Brigadeer General Courtney Whitney, head of SCAP’s government section, to assemble a team of SCAP personnel to draft a “model constitution” that could “serve as a guide” for the Japanese. Of course, what that really meant was just drafting a plan the Japanese would approve–nobody actually labored under the impression that this was just a model.

To guide him, Whitney was given just a couple of notes on a piece of paper that has since been lost. According to those present, the notes were essentially: the emperor must rule by the consent of the people, war should be abolished (more about this in a second), Japan should rely on the, “higher ideals which are now stirring the world” while the “feudal system of Japan will cease.” Finally, the peerage should be abolished, and budgetary affairs arranged, “after the British system.”

This is obviously not a lot to go on when it comes to building a constitution, not least of all given that the team assembled by General Whitney to do the drafting in February, 1946 was promptly set up in the sixth floor of Tokyo’s Daiichi Seimei Building (which SCAP had requisitioned as its HQ) and told they had a week to put together a draft.

The functional draft was done in six days. By comparison, America’s constitutional Convention in Philadelphia ran from May 25 to September 17, 1787–so 116 days, or about 16 and a half weeks if I’m doing my math right.

Now, the deliberations of this group are well documented and extremely fascinating; everyone involved was pretty clear on the significance of what they were doing, and documented their thought processes clearly. Of course there’s no way for us to meaningfully touch on everything that was done in what was fundamentally a ground-up rewrite of the entire Japanese system of government–not constitutional revision, but a full on scrap-and-redo.

That said, there are a few areas I’d be remiss not to touch on. For example, MacArthur’s dictum that the “feudal system” of Japan be undone resulted in a sweeping chapter 3 entitled “the rights and duties of the people” and intended to codify a wideranging swath of rights equal to (or in some cases exceeding) the American bill of rights.

Thus, Article 13 spells out an explicit right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”–a direct reference to the language of the Declaration of Independence. Articles, 16, 19, 20 and 21 lay out rights of freedom of assembly, thought, association,religion and speech broadly equivalent to the legal rules around America’s first amendment, and articles 33 through 39 lay out requirements for warrant procedures and habeus corpus similar to the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth amendments.

But in other cases, the Japanese document goes quite a bit further–a reflection of the fact that, while MacArthur himself was a Republican, most of those who signed up to work for the Truman administration were good ol’ New Deal Democrats invested in a far less hands-off approach to government.

Thus, for example, Article 23 guarantees academic freedom, while Article 26 guarantees the right to an equal education. Article 28 protects unionization rights. My favorite, Article 25, guarantees a right to “minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living”–and oh boy, is there a BOATLOAD of legal scholarship about what that means in practice.

Probably the most remarkable additions, however, are articles 14 and 24, which collectively prohibit discrimination under the law and enshrine the equality of men and women in marriage–essentially, constitutionally guaranteeing the rights of women.

These two articles were the brainchild of one of the most fascinating figures involved in this story, and the only one with any previous experience in Japan: Beate Sirota. She was born in 1923, the child of Austrian Jews who fled that country during the rise of the Nazis–her father was a music teacher, and managed to land a job at Tokyo’s Imperial Academy of Music (today’s Tokyo University of the Arts).

Sirota would live with her parents in Tokyo for 10 years before moving to the US in 1939 to attend Mills College (American schools weren’t exactly welcoming to Jews given the histories of anti-Jewish quotas in this country, but a better option than European ones at the time). She was thus separated from her parents at the time of Pearl Harbor, and ended up marrying a US citizen and naturalizing during the intervening years. After the end of the war, given her ability to speak Japanese, she was a shoe in for the SCAP bureaucracy.

Sirota’s first-hand experience seeing how women had been treated in the prewar system led her to insist on the inclusion of Articles 14 and 24; any other attempt to enshrine the rights of women, she insisted, could be undone by a simple vote in the Diet the moment the Americans left town.

The other much-debated aspect of the constitution is, of course, its most controversial inclusion: Article 9, which I am just going to read to you in full: “Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

That’s obviously pretty sweeping: neither of the two Germanies, for example, did anything of this sort. To my knowledge the only other country to ever abolish its military is the mighty powerhouse of Costa Rica.

The origins of Article 9 are…contentious among scholars, to put it lightly. MacArthur had included it in his initial brief on the new constitution; there’s a lot of debate whether it was MacArthur’s idea originally, or if he was interested by one of the old school liberals in Japan who had survived the war years: Shidehara Kijuro, who had been a diplomat in the 1920s and watched the military undo all his hard work in making Japan a part of the global community, and who thus wanted to ensure the military would never be in a position to influence policy again.

Regardless, the origin doesn’t strictly matter–only that Article 9 was included. It was watered down a bit from the original language, though; Charles Kades felt MacArthur’s initial draft–which banned war even for self-defense–was a bit extreme, and so deleted that language from the text.

And that change would have big impacts down the line–it’s the basis on which the current iteration of the Japanese military is founded.

The final draft of this new constitution was presented to Japanese government leaders on February 13 in a private meeting led by MacArthur’s right man, General Courtney Whitney. Whitney started off by announcing that the old Matsumoto draft was “wholly unacceptable to the Supreem Commander as a document of freedom and democracy”–he then distributed the new American draft, and left the Japanese to read it, quipping once they were done that he’d been “enjoying their atomic sunshine” while waiting.

That’s a quote from Whitney directly, who also recalled with relish that at that moment a B-29 bomber happened to fly overhead.

Even without that bit of needling I don’t think anyone in the room could have mistaken what was going on here, and indeed despite the objections of basically every Japanese leader in the room–all of whom felt that the text was too extreme in its liberal trends–the new “example” was promptly kicked up the chain. Emperor Hirohito loathed the text, which hugely reined in the imperial throne, but felt he had no choice. He submitted the new constitution to the Diet as an amendment, following the procedure of the old Meiji Constitution. It was promptly ratified, the only time the Meiji Constitution was ever successfully amended. It went into effect in 1947, and has remained in place with no amendments or modifications ever since.

The constitution was emblematic of the drive to democratize Japan; SCAP even published a fun series of cartoons explaining in simple language how the old system compared to the new–I’ll include some examples in the show notes.

But as time went on, of course, democratization and demilitarization became less important than that third goal: making Japan into an American bastion in Asia. The biggest impetus of course was the rise of the Cold War, and in Asia in particular the rise of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the start of the Korean War in 1950.

There were a few other factors at play, though. Most notably, General MacArthur had his eyes on a potential Republican run for president more or less from the time WWII ended, and was worried about attacks from his right accusing him of (in essence) allowing “reds” to run rampant in Japan–both the number of left-wing new deal policies SCAP had implemented and the fact that political liberalization had allowed Japan’s socialist and communist movements to re-emerge represented political vulnerabilities for MacArthur.

And this was a big issue for him; MacArthur actually pushed for a formal peace deal with Japan in 1947 because he’d said he wouldn’t pursue politics until that happened, and if there was a treaty in 1947 he could run in 1948.

In reality, he needn’t have worried, as he got crushed in primaries in both 1948 and 52. Still, these concerns about the Occupation enabling the rise of the extreme left in Japan led to some pretty dramatic policy shifts over the course of the era–a phenomenon we collectively call the Reverse Course.

Just to give you an idea of some of the changes implemented as a part of the reverse course–May 1, 1946 was the first May Day, a traditional socialist holiday, since the end of the war. Mass leftist demonstrations (about 1 million workers just in Tokyo) were largely peaceful, mostly focused on issues of food insecurity that plagued Japan early in the postwar. The most dramatic occurrence was a group of just over 100 protestors managing to force their way onto the grounds of the imperial palace–not by hurting anyone, they just pushed past guards to deliver a letter to the imperial household asking the emperor to intercede on the food issue.

This didn’t stop MacArthur from labeling the whole scene as a “violent demonstration.”

Nor did the shift stop there; early in the Occupation years, Japan’s economy was obviously not in great shape. An economically devastating war will do that to you. And so the major unions, assured of their right to organize under the new Constitution, planned a massive general strike for Feb 1, 1947–the goal being to demand better wages to help their members survive the economic turmoil of the age.

That plan came to a screeching halt when MacArthur announced he was outlawing the general strike on the grounds that it would be too disruptive–literally hours before it was supposed to go into effect. Supposedly, union leaders trying to negotiate with government officials right before the strike burst into tears when they heard the news.

Eventually, MacArthur would go so far as to take one of the basic weapons of the Occupation for democratizing the country and turn it on leftists. This was the so-called “purge”–essentially, SCAP directives banning figures from public office.

Early in the Occupation, purge targets were members of the wartime government–officials and bureaucrats associated with the wartime regime, or former officers in the military.

In particular, those targeted for trial at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East–the so-called Tokyo War Crimes Trials, the counterpart of the Nuremberg Tribunal–were purged in the interim.

But those trials were quietly abandoned after the first round of trials ended in December, 1948–that first round had taken far longer than anyone expected, and it was also obvious that future trials would be hard to hold without running the risk of implicating the emperor.

Many of those purged in expectation of a trial–including at least one future Prime Minister who had been indicted for high-level war crimes–were released and eventually “depurged.”

And starting in 1949 and 1950, MacArthur began deploying the purge against socialists and communists in a so-called “Red Purge”–for example, targeting the entire central committee of Japan’s Communist Party after a scuffle between their members and some Americans resulted in the JCP putting out a press release calling their members “martyrs.”

MacArthur’s turn against the Japanese left helps partially explain why, from an initial surge of support in the mid-1940s, the political left would peter out dramatically in Japan (though he’s not the only reason; we’ll get into the others). More notably, it reveals one of the core tensions of the Occupation.

This was, in essence, revolution from above–democracy, American-style, imposed at gunpoint via the whims of a military bureaucracy governed by a single man. And I don’t want to mix my words here; the pre-1945 government of Japan was bad, and its end improved the world. The democratic reforms imposed by the Constitution and other SCAP policies have, on the whole, made Japan a better place in my view.

And yet there will always be a sort of tension–one Japanese right-wingers use to this day to attack the constitution and the postwar order–in a system imposed at gunpoint in the name of “democracy.” Grappling with that legacy is, in my view, one of the key themes–and an unresolved issue–in postwar Japanese society.