Part 3 of our Revised Introduction to Japanese History: the emergence of recorded history in Japan brings with it some more clarity on what’s happening, but also new uncertainties.

Sources

Brown, Delmer M, “The Yamato Kingdom”, and Inoue Mitsusada, “The Century of Reform”, in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 1: Ancient Japan

Fuqua, Douglass. “Centralization and State Formation in Sixth- and Seventh-century Japan” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850. ed. Karl Friday

Kakubayashi, Fumio. “Re-examination of the Political History around Early 6th Century Japan.” Shigaku Zasshi 88 no 11 (1979) (Japanese language)

The JHTI Nihon Shoki translation

Images

Transcript

Right around the year 500, our narrative of Japanese history undergoes a pretty dramatic shift.

For the first time, we can begin to trust in the written accounts left to us describing the period, and we start to move out of the complicated realm of mythohistory and into something a bit more, for lack of a better word, conventional.

Of course, this shift doesn’t represent a precise “line in the sand”, so to speak–it takes place over a period of transition. Even placing it precisely can be a bit challenging.

Here, we run into trouble because of an unfortunate twist of fate. As I mentioned last week, the oldest extant histories from Japan are the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, which date from 712 and 720 respectively; both texts get progressively more reliable as they move closer to the present day, with a shift away from accounts of gods and heroes towards what we might call more conventional political history.

However, neither is actually the first written history in Japan–both make reference to a pair of texts written a century earlier, the Tennoki and Kouki, ascribed to one of the legendary figures of Japanese history, Prince Shotoku (about whom we will have more to say in a bit). Unfortunately, both histories were also lost during one of the great disruptions of early Japanese history (the focus of next week’s episode), with the only known copies being burned.

Both also make references to histories written by Japan’s various clans that, “already differ from the truth and contain many inaccuracies”–to quote the preface to the Kojiki. None of those older histories remain to us either.

Presumably, the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki are based at least in part on some of the same sources those earlier texts were, but we have no way of knowing what we don’t know (so to speak), in terms of material lost to the mists of time.

Still–a combination of archaeology and careful reading of what texts have come down to us mean that the historical record starts to look a bit clearer around 500 CE, though the picture that emerges is not a pretty one.

The 400s are often described as the period of Yamato ascendancy, when the kingdom of the Yamato dynasty–the ancestors of Japan’s modern imperial family–rose from a minor principality based outside Nara to the dominant political force of Japan’s home islands. These early kings accomplished this feat by a combination of shrewd diplomacy and alliance-making alongside military prowess–though their rule was a bit tenuous, as it required balancing the power of several powerful aristocratic clans that had either been defeated or subordinated by diplomacy.

Still, the results were impressive–by 500, the Yamato kings ruled the southern 2/3rds of Honshu, all of Shikoku, and Kyushu (though its hold there was relatively weak).

In addition, the Kingdom’s power extended onto the Korean peninsula itself, where it had at least one client state among the peninsula’s many divided kingdoms (the kingdom of Gaya, on the southern end of the peninsula west of what’s now Busan).

The records available to us also make it clear that starting around 500, this careful balance of power began to falter, with the Yamato kingdom encountering several setbacks. These setbacks in turn would force a re-evaluation of the previous balance of power, which would lay the groundwork for some pretty dramatic changes in the nature of the Yamato kingdom itself.

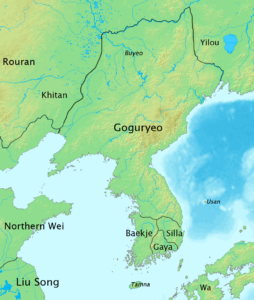

The first major setback was on Korea, where the peninsula had been divided into a series of warring kingdoms for centuries (with their wars likely driving a process of migration from Korea into Japan).

Starting right around 512 CE, two of those kingdoms–Baekche and Silla–began to aggressively expand southward, looking to extend their control into the Yamato-backed kingdom of Gaya. In that year, an envoy from Baekche arrived in the Yamato heartland, carrying a petition asking the Yamato kings to recognize Baekche’s control over four districts that were a part of the Gaya area.

After much debate, the court of the reigning emperor Keitai decided to accept the demand–the Nihon Shoki actually ascribes the acceptance of this demand to the fact that, “Ootomo no Oomuraji and Oshiyama, Hodzumi no Omi, Governor of the Land of Tari, had received bribes from Pekche.”

When Baekche envoys returned the next year to demand another district, the court of emperor Keitai–driven perhaps by a realistic appraisal of Baekche’s strength and a desire to have them balance out Silla’s growing power in Korea–not only accepted the demand but dispatched troops to force the king of Gaya to accede to it as well.

By 527, Silla’s power in particular had grown to such an extent that the court decided to dispatch an army (60,000 troops, according to the Nihon Shoki, though I would be very hesitant to accept those numbers) to drive them back. However, for reasons we’ll get into in a second the army was delayed for two years in arriving–and when it finally did, its commander Kenu no Omi was greeted with a challenging situation.

His orders were to use his forces to get the two Korean kingdoms to negotiate a viable settlement on Gaya’s future, but neither one would meet with him–when a Silla commander did eventually agree to sit down, it turned out to be a ruse to sneak troops into Gaya and raid four villages there.

Eventually, the Kingdom of Gaya itself requested that Kenu no Omi be recalled–presumably because his armies were eating up local supplies without accomplishing anything.

A few short years later, the remainder of Gaya was incorporated into Silla–a major setback for Japanese influence on the peninsula.

To make matters worse, the growing power of Silla was having an impact back at home as well–specifically on what was probably the most loosely held possession of the Yamato court among the Japanese islands.

Kyushu was, naturally given the distance from the center in the modern Kansai area, an area where the influence of the Yamato kings was comparatively weak. That issue was reinforced by the island’s own geography–it is split roughly into thirds by a pair of mountain ranges running east-west across the island, the Tsukushi mountains in the north and the Kyushu mountains in the center. The southernmost third of the island was home to peoples like the Kumaso and Hayato who are described in the early histories as ethnically distinct from the wajin, or Japanese–it was nominally under the authority of the Yamato kings but loosely held and given little attention because at the time, it was not a major agricultural center (and thus not that useful for tax purposes).

The northern band facing Korea had close ties to the peninsula given its proximity, but was also ruled by the Munakata clan, a family closely allied with and very loyal to the Yamato kings.

The middle band, meanwhile, was home to a series of different clans–and in 527 a powerful local leader in the area, known to history only as Iwai, launched a rebellion against the court. The Nihon Shoki once again suggests he was bribed by the kings of Silla to do this–but it’s quite possible that Iwai was driven purely by self-interest and a desire to carve out more power for himself in an area far from the court’s control.

His rebellion was eventually put down–Mononobe no Arakahi, a general from the powerful and aristocratic Mononobe clan came down with an army to crush him–but the rebellion took a great deal of time to bring under control (and was the reason that army to reinforce Gaya was so delayed).

Things were, simply put, not going great for the court–and it’s possible they were actually worse than we know.

You see, a few years after this in the early 530s (531 being the common date, but precise dating is still tricky at this point) Emperor Keitai died.

He had plenty of children, including three sons who grew to adulthood–so finding a successor wasn’t an issue. However, what came next is a bit odd.

The succeeding two emperors Ankan and Senka–whose dates are a bit challenging to pin down–both had very short reigns, so short that the Nihon Shoki deals with them in a single combined chapter. They are then succeeded by emperor Kinmei, whose reign is far lengthier (22 years, versus a combined 8 in the traditional counting for Ankan/Senka).

And that’s a bit odd, to put it mildly, which has led to some interesting theorizing around potential omissions to the historical record. There’s a few competing theories flying around as to what might be going on here; one, associated with the post-WWII scholar Hayashiya Tatsusaburo, is that after Keitai’s death there was actually a civil war between two factions of the imperial line (the Ankan/Senka faction and the Kinmei faction), which was then deleted from official histories because division within the imperial family reflected badly upon the throne and its legitimacy. That war was supposedly specifically about Korean policy, with the Ankan-Senka line backing an attempt to aggressively return to Korea (with the help of the powerful clan omuraji, or chieftain, Otomo no Kanamura), and the Kinmei line (backed by another powerful clan omuraji, Soga no Iname) favoring abandoning Korea and strengthening the dynasty’s position at home.

That theory is less widely accepted today, simply because there’s not much beyond purely circumstantial evidence to back it. However, it’s not even the most out-there one; another scholar, Mizuno Yu, promoted the idea that the imperial family of today are actually usurpers who seized the throne during the reign of Emperor Keitai’s predecessor Buretsu right around 500 CE–everything before that is the history of a totally separate dynasty. He based this on the fact that Buretsu was not actually a direct descendant of the previous emperor, who had no surviving children according to the histories, but a distant relative–a fiction, argued Mizuno, to cover up the reality of usurpation.

Slightly less extreme is the theory associated with Kakubayashi Fumio, who argued that since most of the powerful clan leaders close to the court remained unchanged over the Keitai-Ankan-Senka-Kinmei period, it’s unlikely there was a massive war or upheaval (for example, Mononobe no Arakahi, the general who crushed the Kyushu Iwai rebellion, had a long career spanning all these reigns). However, he did suggest that Ankan and Senka’s short reigns might have resulted from “unfortunate accidents” arranged by a powerhungry Kinmei and his supporters.

Realistically, it’s unlikely we’ll ever know what happened for a certainty because of the limited sources available to us–all of which are, of course, imperially-sponsored histories designed to paint the imperial family in the best possible light. It’s interesting to speculate, and there’s a lot of good scholarship on the question of what the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki might or might not be leaving out if you’re curious, but that’s not a question we can really resolve here.

I have to admit, there’s a part of me that does suspect much of this explosion of theorizing, which burst onto the academic scene starting in the 1950s, has less to do with hard evidence and more to do with scholars enjoying the freedom to ask these kind of questions–where before WWII, questioning the legitimacy of anything to do with the imperial line was a fast road to social ostracization and job loss (if you were lucky) and a prison sentence for defaming the throne (if you were not).

All we can say for certainty is that eventually, Kinmei took the throne (possibly by assassinating his own brothers, but hey–family’s complicated sometimes, right?) And it is pretty clear that his reign represented a massive policy retrenchment from his predecessors.

It also represents a big shift in history, because from this point onward thanks to domestic and foreign sources, our ability to date things becomes far easier–Kinmei, officially the 29th emperor, is the first one for whom key figures and dates are verifiable by modern historians.

But that’s not the only reason he’s noteworthy. For one thing, Kinmei did move away from active involvement in Korean politics, preferring instead to support one of the contenders on that peninsula (the Kingdom of Baekje) whose rulers were friendly to Japanese interests (given that Kinmei’s dad had granted them a bunch of land from the former kingdom of Gaya).

For another, Kinmei radically altered the balance of power between clan leaders underneath him. Remember, during this point the emperor was more of a coalition ruler governing a host of powerful clans allied to his line–for much of the preceding reigns, the most powerful of these clan rulers was Ootomo no Kanamura, head of the powerful Otomo clan (and unrelated to the later samurai family of the same name, if you’re wondering).

Kinmei (possibly worried that the Otomo would treat him as a puppet ruler) decided to remove Kanamura from positions of influence, with the backing of his own close allies from two rival clans–Soga no Iname and Mononobe no Okoshi.

Going forward, Kinmei and his successors would reign with the help of the Soga and Mononobe clans, who would collectively be the “second families” of the nation.

And their help would be important, because Kinmei undertook a big policy of domestic retrenchment during his rule.

From what we can tell (and it’s hard to say without administrative records), before Kinmei the actual administrative power of emperors outside the imperial heartland in the Kansai area of Honshu was pretty weak. Largely, they seem to have relied on local families to manage things and pay tribute/taxes back to court–which made for powerful local rulers who could challenge the authority of the emperors by cutting off said tribute if they wanted to (as happened with the Iwai Rebellion).

Kinmei began to set up royal estates in other parts of the country controlled directly by the throne, giving him access to wealth and resources from more of the country–and implementing census systems of families living in the area to more effectively tax them, using methods learned from Korean and Chinese advisors (especially Baekje, which regularly sent advisors to share administrative techniques).

The Soga clan in particular was central to this exchange, with Soga no Iname developing close ties to the Korean peninsula and leveraging them to make himself a key go between in the importation of these new techniques (and of more traditional trade).

In fact, honestly, while I have been saying up until now that “Kinmei” did x or y reform, it’s kind of hard to escape the feeling that in reality, Soga no Iname was responsible for those reforms–and Kinmei was just the puppet used to publicize them.

That’s because from Kinmei’s reign on, for the next 100 years or so, the Soga clan would absolutely dominate Japan’s political scene. For example, Kinmei would marry two daughters of Soga no Iname (Soga no Kitashime and Soga no Oane), and while his successor Emperor Bidatsu was not from these relationships (he was born from a marriage to Kinmei’s own niece, the daughter of Emperor Senka), future rulers would be.

Even after Iname’s own death in 570, his successors as heads of the Soga family would continue to wield substantial influence over the court.

In a certain sense, Soga no Iname and his successors established a pattern that is pretty central to Japanese history–the practice of the use of puppet rulers. As we’ll see going forward, it’s something of a motif of Japanese history–putting forward a symbol to reign while someone else rules behind the scenes. There are many reasons why this sort of convenient fiction can be worth keeping up–for one thing, a puppet ruler might possess legitimacy you yourself do not, making keeping them around worthwhile to avoid challenges to your control. This is something we’ll return to quite a bit over these episodes, but I just want to note it here.

In addition to establishing this pattern of powerbroking, Soga no Iname is also responsible for one of the most important shifts in early Japanese history thanks to his connections to the Korean peninsula.

Some time during his time in office–the precise date is somewhat controversial, with the most consistent options being either 538 or 552 CE– the King of Baekje, the Yamato kingdom’s strongest ally on the Korean Peninsula, sent to court a series of ritual objects associated with a newfangled religion that had been sweeping the mainland: Buddhism.

If you’re wondering why the date is controversial, it’s because differing sources give different ones–generally, the 552 date is associated with the Nihon Shoki, while 538 comes from the other extant histories of the period. We don’t know which is accurate, nor does it necessarily matter all that much.

What really matters is that when these gifts were received, the reigning emperor Kinmei supposedly gathered his advisors and asked them whether these gifts (which supposedly included a Buddha icon as well as several copies of sutras, or Buddhist religious texts) should be accepted and if this newfangled religion should be venerated by the court.

And supposedly, it was Soga no Iname who proved the strongest voice in favor of the new religion–leading to the court adopting Buddhism and offering support to the first temples intended to propagate it.

It’s worth noting that, while this is often pointed to as the introduction of Buddhism in Japan, it’s very likely that Korean merchants or refugees had brought the religion to the Japanese islands in earlier years. After all, the religion was quite well established in Korea by this point. However, this is the moment associated with the religion’s adoption by the imperial court–thus introducing it to the elite of the country (who coincidentally are the only ones recorded in the historical record at this point).

Now, Buddhism is obviously a pretty important phenomenon in Japanese history–and given that we’ve still got about 1500 years of history to go from this point, its story in Japan is a very long one.

Indeed, in general Buddhist history is quite long–as a religion, it was already 1000 years old by the time these first official contacts were made. Its founding is, of course, associated with the Buddha, a.k.a. Siddartha Gautama, also sometimes known as the Shakyamuni Buddha–because there are multiple Buddhas in Buddhism.

As a rule, though, if anyone says “the Buddha” they usually mean Shakyamuni–if it’s another Buddha like Maitreya or Baisajya/Yakushi, they’ll usually specify with the name.

In its original homeland of India, Buddhism was outcompeted, so to speak, by competing traditions like Hinduism, Islam, or Sikhism (but never disappeared altogether). It found its greatest success spreading outside of India itself, in one of two directions. One was to the southeast, to places like Myanmar or Thailand–home ot what today is called Theravadan Buddhism.

The other was to the north and west, into what’s now Afghanistan and Pakistan (where, by the way, the Greek elite deposited by the conquests of Alexander the Great created a fascinating hybrid Buddhist/Helenic culture that created, for example, works of art showing Hercules defending the Buddha while he meditated to reach enlightenment). From there, this form of Buddhism spread around the Himalayan mountains (which make it quite hard, to put it mildly, to go directly from India to China) and came into China from the northwestern Silk Road during the latter years of the Han dynasty in roughly the 150s CE.

Buddhism never became a dominant religion in China–it competed fiercely with domestic religious movements like Daoism, and while at times during later dynasties it enjoyed official sponsorship eventually that support shifted over to Confucianism, the ideological and spiritual underpinning of later imperial dynastic politics.

However, it remained a powerful cultural force in China, and from there expanded into Vietnam, Korea, Tibet, and eventually Japan as well–these countries are home to what is called Mahayana Buddhism, the branch of the faith that tends to dominate in East Asia. We’ll talk more about Mahayana and what makes it distinctive in future episodes, but for now I want to briefly introduce this division and these terms since they’re useful for talking about Buddhist history going forward.

Of course, for some in Japan the appeal of Buddhism was purely religious–after all, its message of freedom from earthly suffering is appealing, to say the least, which is why it remains one of the largest religions on earth. But, though they never explicitly stated this, a good part of the appeal of early Buddhism in Japan was political–the faith offered connections to the powerful regimes of the Asian continent, and its growth in some of the most powerful neighbors Japan had made it, for lack of a better term, fashionable, or even cool.

This was pretty clearly the angle taken by Soga no Iname, and here I’ll quote a bit from the Nihon Shoki’s description of this whole debate, which begins with the Emperor Kinmei asking his advisors about the Buddha statue gifted by Baekje: “”The countenance of this Buddha which has been presented by the Western frontier State is of a severe dignity, such as we have never at all seen before. Ought it to be worshipped or not?” [Soga no Iname] addressed the Emperor, saying:–“All the Western frontier lands without exception do it worship. Shall…Yamato alone refuse to do so?”[Mononobe no Okoshi and Nakatomi no Kamako] addressed the Emperor jointly, saying:–“Those who have ruled the Empire in this our State have always made it their care to worship in Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter the 180 Gods of Heaven and Earth, and the Gods of the Land and of Grain. If just at this time we were to worship in their stead foreign Deities, it may be feared that we should incur the wrath of our National Gods.”

In the Nihon Shoki account, Kinmei decides to give the icon to Soga no Iname for him to worship–presumably, if this goes well, the rest of the court will be ordered to adopt Buddha worship. However, things do not go great–the land is wracked with pestilence, which the anti-Buddhist Mononobe and Nakatomi clans blame on this newfangled god and the abandonment of traditional worship.

Kinmei agrees and orders the Buddha image thrown in a river and the temple around it burned–but, the Nihon Shoki notes, Hereupon, there being in the Heavens neither clouds nor wind, a sudden conflagration consumed the Great Hall (of the Imperial Palace).”

So that’s a bit of a wash, as omens and portents go, and going forward the Soga clan would continue to be associated with Buddhism–and use their Buddhist connections to the mainland as a vehicle for trade and cultural exchange, massively enriching their clan in the process.

And this would be a big part of how the Soga clan came to dominate Japanese politics, because while during the generation of Emperor Kinmei the balance of power did not tip decisively towards the Soga, in subsequent generations it would. The emperor after Kinmei, Bidatsu, was not of Soga lineage, and so during his lifetime the balance of power remained much as it was.

But starting with Bidatsu’s death in 585 and the ascent of his successor Emperor Yomei, the next three emperors were all of Soga stock. Yomei and his brother and successor Sushun were both children of Emperor Kinmei by one of his Soga clan wives, as was Empress Suiko–one of Japan’s empress regnants, also a Soga descendant by way of Emperor Kinmei as well as the former spouse of Bidatsu (and, by the way, the first woman whose reign is historically verifiable).

Their successors, Emperor Jomei and Empress Kyogoku, were not of Soga descent, but had been placed on the throne by Soga clan influence and thus were politically close to the family. So really, starting in 585 all the way up to 645 CE, the state was effectively dominated by the Soga clan.

That domination, however, was not a matter of pure marriage politics–it was because after the death of Emperor Bidatsu in 585, the Soga ensured their preferred candidates would succeed using force.

After Bidatsu’s death, a succession dispute once again wracked the imperial clan–these were not uncommon, given that the social norms of the time allowed the emperor multiple female partners and thus ensured a great many heirs floating around.

Which hey, is nice since you don’t have to worry about running out–but all those heirs also represented an opening for ambitious politicians looking to secure power by placing a preferred candidate atop the throne.

Specifically, after Bidatsu died, he left behind three sons who could succeed him–though only two enjoyed the backing of powerful clans. The first was his eldest son Prince Oshisaka–backed by the Mononobe clan and its powerful omuraji leader Mononobe no Moriya. The second was prince Oe, son of Emperor Bidatsu by his Soga clan concubine and backed by the Soga clan omuraji and son of Soga no Iname, named Soga no Umako.

Oe was successful in taking the throne, but also sickly–he lasted only two years before he died and left the empire in one more succession crisis. This time it was Prince Anahobe, an ambitious young heir to the throne, versus Prince Hatsusebe, another child of Emperor Kinmei by one of his Soga clan wives. And this time, thanks to the ambition of Anahobe, things came to outright blows–Anahobe is said to have encouraged the Mononobe to take up arms, because he was prideful and vain and could not handle challenges to his own authority.

So much so, in point in fact, that he’d already triggered a few different political crises over the course of his career–the biggest of which took place when he tried to sneak into the emperor’s inner chambers (his harem, in other words), to assault one of his father’s own wives–the future empress Jito. Only a scrupulous warrior who refused the prince access on the grounds of impropriety stopped him–and for his troubles, Anahobe had said warrior killed.

So not a great guy, all told, but Mononobe no Moriya was willing to overlook that if it meant getting his preferred candidate on the throne. And so this time, the succession dispute became an all out civil conflict between the rival claims of Hatsusebe (backed by the Soga) and Anahobe (backed by the Mononobe).

According to the Nihon Shoki, at first the Mononobe side had the advantage–until the Soga army was cornered at a place called Mt. Shigi in the area of Osaka. At this last stand, a new figure took center stage–a teenage prince named Umayado, son of the former emperor Yomei. I’ll quote from the Nihon Shoki’s description of the prince’s action: “So he cut down a nuride [laquer] tree, and swiftly fashioned images of the four Heavenly Kings [of Buddhism].[1869]” Placing them on his top-knot, he uttered a vow:–“If we are now made to gain the victory over the enemy, I promise faithfully to honour the four Heavenly Kings, guardians of the world, by erecting to them a temple with a pagoda.” ….Soga no Umako also uttered a vow:– “Oh! all ye Heavenly Kings and great Spirit King,[] aid and protect us, and make its to gain the advantage. If this prayer is granted, I will erect a temple with a pagoda in honour of the Heavenly Kings and the great Spirit King, and will propagate everywhere the three precious gems.”

Those gems, if you’re wondering, are the Buddha (and the veneration of his teachings), the dharma, or the truth of buddhist law, and the sangha, or Buddhist priesthood. The four heavenly kings, meanwhile, are powerful divine figures within Mahayana Buddhism–Bishamonten, Tamonten, Zochoten, and Jikokuten are their names in Japanese. Collectively, they guard the four cardinal directions and protect the Buddhist law.

And lo and behold, the Soga armies then turned things around and crushed the Mononobe, killing the clan’s leadership as well as the corrupt Prince Anahobe and his supporters in the imperial clan–and securing victory for Prince Hatsusebe, now known as emperor Sushun.

And at his side was the former emperor Yomei’s son, the teenage prince Umayado–though he’s generally known much better by the honorific he received after this moment, Shotoku Taishi. Prince Shotoku, though neither he nor his descendants ever sat upon the throne, would eventually become a revered figure particularly for his defense of Buddhism–and be the subject of cultic worship for several centuries going forward.

By the way, the temple Shotoku and Soga no Umako promised to found? They kept that promise–Shitennoji (the temple of the four kings), now within the limits of modern Osaka, is one of Japan’s oldest Buddhist temple, though the grounds have been moved and the buildings lost to war or natural disaster several times over the years.

Indeed, arguably Shitennoji is the oldest still extant temple in the country, though there is some dispute whether it or Asukadera in Nara prefecture was founded first.

The Soga victory in this succession conflict (known to history as the Soga-Mononobe War) thus secured a few crucial changes going forward. Buddhism would be not only tolerated but supported as a state religion–though always alongside the native religious traditions that today form the basis of Shinto, never supplanting it completely.

The destruction of the Mononobe–a powerful family with an interest in maintaining a decentralized state–opened up a chance for centralizing government reforms. In particular, in 604 that same Prince Shotoku who had supposedly rallied the troops in defense of Buddhism helped draft a new 17-article legal code, based on models from the countries of the Asian mainland. That code was far more centralized than anything that had come before–we’ll have more to say about it in a future episode.

But most importantly, victory secured the position of the Soga, who were able to use their military strength and their close marital alliance with the Imperial family to dominate politics going forward. That new more centralized government? Well, it empowered the Soga clan leadership just as much (if not more) than the imperial throne.

But Soga domination was lot to last forever–a great change, perhaps one of the greatest in Japanese history, was on the horizon. That moment–next week.