This week: Osaka enters the modern era. How did the nation’s kitchen become the “capital of smoke,” and how did the city’s government attempt to remake it for the modern era?

Sources

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan.

Images

Featured image: A street view of Sennichimae, Chuo-ku, Osaka in 1916. (Image source)

French officers drilling the shogun’s troops in Osaka in the 1860s. (Image source)

A scene of the Dōjima Rice Exchange created by artist Yoshimitsu Sasaki in the 1880s. (Image source)

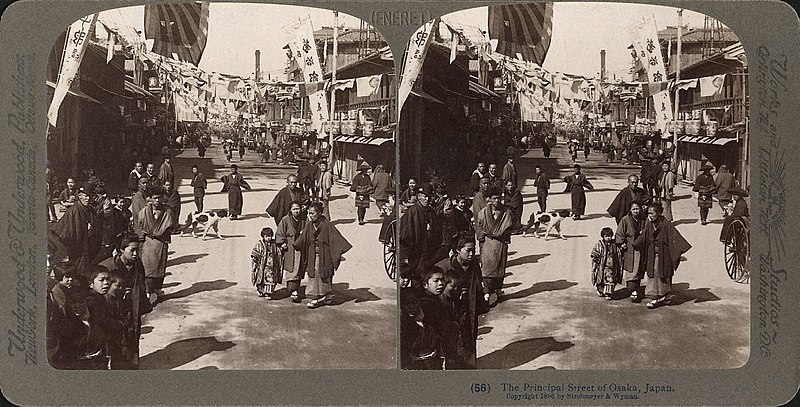

An 1896 photograph labeled as a scene of the “principle street” of Osaka. (Image source)

A view of the mint from 1907. (Image source)

Osaka Sakaisuji in 1914. (Image source)

Transcript

Given that the Tokugawa shogunate was, in a very real sense, built upon the mercantile foundations of Osaka, one supposes it is only fair that the shogunate would come to an end there too–at least in a certain sense.

For a start, it was in Osaka castle that the 14th shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi, made his home late in 1865 as he prepared to lead the armies of the shogunate on campaign. Well, I say, ‘lead’, but that’s a bit of a misnomer–Iemochi was all of 20 when the campaigns started in the summer of 1866, and had never led the troops of the shogunate much of anywhere outside of a parade ground. But that was ok; his presence was more symbolic as his advisors handled everything, and at any rate, said campaign was only against a single rogue domain: Choshu, whose renegade leaders had already been defeated once but apparently had not learned their lesson. How hard would it be to do the same thing again?

Well, pretty hard, it turned out. In point of fact, the shogunate’s armies were demoralized and poorly lead, and unable to make headway anywhere in Choshu. And to make matters worse, the always sickly Iemochi took ill suddenly and died in the fall of 1866.

Now, Iemochi was not much of a loss as a strategist, to be perfectly if somewhat cruelly clear. But he was a valuable symbol, both because of his closeness with the emperor and imperial court–important as a symbol of national unity–and because he represented that all-important thing: a warm butt in the chair, who could hold the office of shogun and put on a nice face while his advisors did the real work of trying to steer the ship of state.

Without Iemochi, things ground to a halt inside the halls of Osaka castle, as his advisors stopped everything to try and figure out who their new putative boss was now–a crucial loss at a moment where a lack of clarity was not the sort of thing easily afforded.

Of course, technically the end of the Tokugawa shogunate as it’s often observed came a year later, when the guy they actually settled on, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, assembled his followers in Nijo castle in Kyoto and announced to them his plan to hand power back to the emperor and imperial court in accordance with the wishes of those strange radicals in Choshu.

But even then, Osaka castle was where Yoshinobu retreated to two months later–apparently having changed his view, and deciding to make a go of fighting Choshu and its growing list of allies for control of the country. And so it was within Osaka castle that Yoshinobu got the news that his forces had been defeated when they tried to march on Kyoto and seize the emperor from their enemies–and it was from Osaka castle that he had to flee by boat when news came that said enemies were now marching south toward the city.

After that moment, Yoshinobu gave up the will to fight–some of his followers would continue on for over a year beyond this point, but for the 15th and last shogun of Japan it was at Osaka castle that the Tokugawa shogunate as an idea breathed its last.

The battle that sapped the shogun’s will, at Toba and Fushimi on the southern outskirts of Kyoto, took place on January 31, 1868. Osaka Castle itself fell to the advancing forces of a newly minted “Imperial Japanese Army” two days later on February 2nd, without a single shot being fired. Once word got out that Yoshinobu had retreated east back to Edo, the remainder of the garrison abandoned the castle as well–and the fortress that was supposed to serve as the bastion of the shogunate’s authority in Western Japan was left undefended.

Those early days must have been quite something to live through for the residents of Osaka. The new imperial government in Kyoto which had just seized their city was dominated by a nebulous group calling themselves imperial loyalists–and this always makes me think of an anecdote about the Kinnoto of what’s now Kouchi prefecture on Shikoku, one of the local loyalist movements of the early 1860s. The Kinnoto founder, Takechi Hanpeita, was looking for ideas to fortify his domain against the threat of Western imperialism–and one of his followers, a young idealistic samurai, suggested hitting up the merchants of Osaka for money to do it. Takechi responded that this was a great plan–everyone knew the wealthy Osaka merchants had a lot of money that could go to patriotic causes. But what should be done if, lacking in patriotic spirit, said merchants refused to share their funds?

Well in that case, replied the student, the solution was easy. They should plead earnestly with the merchants, and then if still refused they should commit suicide in the homes of said merchants one by one until at last the non-samurai came around. Takechi’s response to this suggestion is not recorded, but given that the plan didn’t go forward I’m thinking we can guess.

And THESE were the people now occupying the city–one imagines there was a great deal of concern about just how crazy these ‘patriots’ would turn out to be.

And there were some scares early on, particularly in Osaka’s neighboring port of Hyogo–which had been opened up to foreign trade at gunpoint by the unequal treaties, and where the foreign community ended up in a tense multi day standoff with radical antiforeign elements of the new imperial army who threatened to burn all their buildings.

But in Osaka, things were fairly calm. The victorious imperial forces did put a good chunk of Osaka castle to the torch–after all, it was a symbol of the shogunate’s power, so burning it down was…well, you know, symbolism and all that.

But beyond the destruction of a good chunk of the castle–which yes, is a big thing to move beyond, but bear with me–the feared depredations of the city did not come. Admittedly, a big part of that was the fact that the army did not stay very long–in just a few days, its forces were packed up and sent east towards the remaining bastions of the shogunate. So instead, a tense–but peaceful–calm reigned over the city.

In point of fact, most of the extremists of the loyalist movement had been killed off in the fighting of the 1860s; the ones who rose to leadership in the newly-emerging imperial government were far more pragmatic than anything else, and it turns out those are the kind of people that you can work with.

Within just a few months, order had been restored in the city–the new imperial government even arranged for the foreigners to set up shop in Osaka rather than the smaller city of Hyogo, with the US consulate in the city opening in April of 1868.

The foreigners were even paid a small cash indemnity for that whole “almost burning down your stuff in Hyogo” incident, presumably inside of the 1860s equivalent of one of those “I’m sorry” cards you can buy at the grocery store.

There were, of course, still quite a few changes. The administrative reorganizations that came after the fall of the feudal state saw Osaka organized into its own prefecture, complete with a governor–but still one appointed from the national capital rather than elected locally.

I should also note that this took a while–the decision to incorporate Osaka as a distinct urban prefecture (similar to how Kyoto and Tokyo are both cities and prefectures, while other Japanese cities are not) took until 1889. One day I might do something on the meandering history of administrative divisions in Japan, but that’s not as directly relevant to us now.

The all-important Dojima Rice Market also lost is economic centrality; while the value of rice was still of course quite important in terms of national well-being (similar to how bread and milk are often used as basic cost of living commodities in America), within a few years the new imperial government was moving away from taxation using agricultural products. Which, having spent the last few weeks looking at a system based on just that, fair enough.

The original incarnation of the market shuttered its doors in 1869 as government reforms made it redundant; a revived rice market would open up in 1871, but only for trading foodstuffs–no longer quite as central to the economic history of the entire nation.

Instead, the government began to impose a unitary national currency in the form of the yen, and required it to be the basis of taxation–removing a crucial reason for the Dojima market existing in the first place. The Dojima Rice Market did not go anywhere, to be sure–rice vendors continued to operate there well into the 20th century. But it was no longer central to the nation’s economy because converting rice into currency was no longer a crucial part of how said economy functioned.

Of course, the newly dedicated National Mint that would be responsible for making all those yen did open its doors in Osaka in April of 1871 (which was quite a production; all the machinery had to be imported from overseas, as did crews to demonstrate how paper money printing worked), so in that sense the city was still central to the national economy–but mints don’t actually employ that many people, turns out, given all those newfangled machines.

Plus, of course, the triumph of the imperial cause did not, as some had hoped, result in the center of political gravity shifting back to the west of Japan from the east. Instead, the emperor and his court moved east. Edo had, throughout the Tokugawa period, vied with the older and more established city of Osaka for cultural and commercial dominance–under its new name of Tokyo, it would become the undisputed commercial center of gravity to go along with being the national capital, and the heart of the nation’s culture as well.

This is, of course, something Osakans have taken totally in stride and have never expressed any degree of displeasure with at any point in their subsequent history.

Simply put, Osaka did not have an easy first few decades out of feudalism. The city’s economy didn’t collapse, to be sure, but it did change dramatically. Rather than finance and agriculture, the character of the city shifted towards two closely related enterprises: shipping and industry.

Shipping, of course, makes sense–no political upheaval would change the fact that Osaka was still the endpoint of Japan’s major coastal shipping routes (important because the only real competitor in terms of moving large things around is freight rail, and that would take decades more to set up and has some real limits in terms of geography), and it was still the natural endpoint of shipping routes to and from the Asian mainland going through the inland sea.

And as for industry, well, it makes sense to build up your manufacturing capacity in a port city, since you can then ship all the stuff you make around the country. Plus, there were quite a few decently wealthy families in the area who could invest in a factory or two as they looked to make the jump over to modern-style economies.

This was particularly the case because many of the ‘great families’ of the old merchant class had weathered the transition rather well. Several of the prominent merchant houses associated with trades tied to the feudal system–like rice merchant families–did not make the jump, and 1868 saw a great many bankruptcies following on the heels of the end of the shogunate, and even later in the year, when the government announced a transition away from mixed gold and silver currency and on to the gold standard. Most of the junin ryogae and honshogai money merchants had done business in silver or in exchange bills backed by silver, and as you might imagine a transition away from silver altogether was…not great for them.

And I do mean a great deal of bankruptcies. Tax documents from later periods provide some great evidence of this; one from the 1890s lists companies that paid over 100 yen in taxes plus the year of their founding, and in Osaka only 23% of those companies had founding dates of 1867 or earlier.

But the merchant houses that did survive were buoyed by official policies of the new Meiji government which barred taking overseas loans–a common practice as a method to get the money to pay for all those newfangled bits of technology, but one that had serious political risks. After all, if you take money from foreign banks that are threatening your country with their imperial ambitions, well, now those same foreigners with imperial ambitions have leverage over the very strategic improvements you need to fend them off.

As a result the government largely blocked foreign investment and directed businesses that needed capital to domestic lenders instead. Which meant that if you had survived the tumultuous early years, suddenly you had a government-guaranteed loan market for your business–and while the government was occasionally somewhat boneheaded in what it chose to fund, it was also pretty loose with subsidies.

So, for example, if we look at the families of some of the old junin ryogae, we find that many of them not only survived but thrived under the new order. The Konoike family, two branches of which were a part of the junin ryogae, transitioned into banking–the family had 3 million yen of assets in 1888 and 15 million by 1916. Their bank–the Sanwa Bank–is now a part of the Mitsubishi financial group.

They were probably the most successful of the junin ryogae–many of the others either went bankrupt in 1868 or got out of finance by the 1880s–but even among the smaller moneychangers there were some notable success stories. And then, of course, there was Sumitomo–born from a family medicine shop that got its start in Kyoto in the 1700s before expanding to Osaka, and thanks to some smart investments in the Meiji era one of the massive Zaibatsu firms with 70 million yen in assets by the early 20th century.

What I’m getting at is that Osaka was a city with a lot of money to support industrialization, which helps explain how the city took on that industrial character. Of course, if you’re familiar with 19th century industrial cities, you’ll know that isn’t necessarily a good thing; by the 20th century it had acquired the less than flattering nickname of kemuri no miyako or ‘the city of smoke’, for exactly the reasons you might think.

The name was so ubiquitous it even appeared in primers written for elementary school children, as this quote from a government-approved textbook shows: “It is only natural that Osaka should be called the Capital of Smoke. Even on a fair day, the sky grows dull as you approach Osaka station by train, making the city appear overcast. There are over eight thousand factories here, large and small. Lined up one after another like trees in a forest, their chimneys belch smoke incessantly. With its diversity of flourishing industries, Osaka is truly Japan’s greatest industrial city.”

Smog, and air quality in general, was a major issue–as was poverty, as large numbers of poor people flocked to the city for factory jobs. Osaka was also commonly called Toyou no Manchesutaa or “the Manchester of the East” during this period, and that was not intended to be a flattering comparison–Manchester too had a reputation as dirty and dangerous during this time period.

The city’s population also exploded–there were about 332,000 people living there in 1882, but that number ballooned by an additional 1 million people by 1911–in 31 years! That’s a bit over 32,000 people moving every year for over 30 years on average. As you might imagine, this created some major crunch on the city’s housing supply, leading to massive slums well beyond the capacity of what social housing the city had or could build with any speed. By the 2nd decade of the 20th century, housing crunches were so bad that by the city government’s own estimates, workers living in crowded boardinghouses in the exurbs of Osaka had no more than 2 tatami mats worth of living space to themselves–and on the outskirts of the city, that number dropped to 1.8 tatami mats. In the slums of Nipponbashi, they averaged only 1.08.

As we all recall, of course, a tatami mat is about 3 feet by six feet (or .9 by 1.8 meters). So these are incredibly cramped quarters; for reference, enlisted sailors in the imperial navy were usually allocated about 1.5 tatami mats worth of living space for their berths.

Living spaces weren’t just cramped; they were also of low quality, as reportage from a journalist visiting Osaka’s slums makes clear: ““one first feels the lack of [open] space and the dearth of [single-family] homes. [Then,] inside dwellings, one notices the lack of air and light as well as the absence of plumbing. One also feels the want of parks, playgrounds, and trains.” Ultimately, said article concluded by saying that the workers of Osaka had fusoku seikatsu– “a life of insufficiency.”

And to cap it all off, demand was such that from 1910 to 1922 the average rent in Osaka tripled–which, given the quality of conditions, was…not ideal.

As you might imagine, this sort of treatment did not exactly endear the city’s workers to either their bosses or the city government, and tensions boiled over in the summer of 1918. The city was already seeing some substantial tensions among its workers–strikes and other labor disputes were becoming increasingly common. But what really sent things over the edge was a spike in the price of rice.

That spike was driven by Japan’s participation in World War I, which saw large amounts of rice shipped overseas to help feed the soldiers of the Allies, and by speculating rice merchants buying up large stocks of rice to sell to the government, which was planning a military intervention in Russia’s blooming civil war–and which would need to buy up rice to send with the troops being dispatched to the Russian Far East.

Spiking rice prices in turn effected food prices in general, to the extent that many workers were forced to pawn their clothes or take on second jobs, and even then often had to cut down to two meals a day instead of three just to make ends meet.

That’s not a situation that’s going to lead to terribly happy workers, of course–and starting in July, 1918, Rice Riots began to break out around the country.

In Osaka specifically, things kicked off on August 9 in the slums of Imamiya when hundreds of hungry locals converged on the storefront of a local rice dealer and began pounding on the door with rocks, sticks, and geta– traditional sandal-like footwear made of wood. They demanded the shop sell rice at 1/3rd the market rate of the time.

That evening, 5000 people gathered at Tennoji Park to plan future protests–the police, worried about more attacks on shops, massed at the rally and arrested a young man who had attended.

This turned out to have been a poor strategic decision; when the cops placed the arrested young man into a streetcar to bring him to jail (which I guess is more efficient than a cop car, so that’s good), the crowd stormed forward, freed the kid, and then derailed and burned the next several streetcars that showed up.

Over the next few days, over 230,000 workers rioted through the streets of Osaka–the riots were only brought under control when the mayor, Ikegami Shiro, called in troops, issued a curfew, and ordered all public transit shut down after 7pm.

Before becoming mayor–a job that, remember, was appointed from the Home Ministry in Tokyo, not elected–Ikegami had been the police chief for the city, and his solutions to its social ills were very much grounded in that experience.

Rather different was his deputy mayor at the time of the riots, and one of the more intriguing figures in the history of Osaka: Seki Hajime.

Born in 1873 in Shizuoka, Seki was a consummate man of the Meiji Era–he was educated at what’s now Hitotsubashi University and spent some time in the Finance Ministry before going overseas to Europe to study. Upon his return in 1901, he would pursue a doctorate in law and go into academia, but found the world of academics to be a bit too theoretical and detached from daily life for his taste. To which I do have to say, fair enough.

This was probably why Seki jumped at the chance to go into urban administration. When he was introduced by chance to Ikegami Shiro in 1914 (by way of an old instructor who knew Osaka’s mayor personally), the two hit it off–and Ikegami decided that a book-smart, ambitious young man with big dreams of reform could be valuable to his administration, so he offered Seki the job of deputy mayor. And Seki accepted.

He’d serve as deputy mayor until 1923 when Ikegami retired, and afterwards was appointed as the new governor himself–a job he’d hold until his death of typhus in 1935.

Seki’s time in Europe had led to him landing in the intellectual orbit of a nebulously defined intellectual movement of the early 20th century: the Progressives. Now, that term has some pretty specific political associations today, and there are definitely some throughlines between early 20th-century progressives and the leftists with whom that word is usually associated today. But in the early 20th century, progressivism was simply the ideology of societal reform (usually through government intervention) to make society a better place to live.

Women’s suffrage, for example, was a progressive cause worldwide–as were things like education access and the fight for minimum housing standards. Of course, the movement’s history is not squeaky clean– Prohibition, with its attendant rise in organized crime, was a progressive cause too, and many famous social progressives were also quite racist in their interpretations of what counted as ‘progress’ (basically, the standards of rich white people).

Anyway, all of that is to say that Seki Hajime was very much a dyed-in-the-wool progressive who believed that Osaka’s government had a crucial role to play in improving the lives of all the city’s citizens–and that many of the city’s problems stemmed from the failure to address said problems. As early as 1915, Seki was in charge of committees to discuss social reform issues, and after the 1918 riots, Ikegami decided to empower his young deputy to pursue even grander visions of social reform.

Seki’s plans to do just this would come together over the years, first as deputy mayor and then as mayor in his own right. I’ll do my best to provide a brief sketch of them here–given that he’s sometimes called Osaka no chichi, or the father of Osaka, his vision for the city is worth spending some time on!

Simply put, Seki was an urbanist to the core. Unlike many within the upper levels of the imperial leadership at this time, who viewed cities with some mistrust as hotbeds of radicalism and looked to the countryside as the home of ‘traditional Japanese values,’ Seki Hajime saw Japan’s cities as the heart of national culture. The reason cities had become such hotbeds of radicalism, he said, was simply because their residents had been ill-used–exploited by landlords and bosses who squeezed them for everything they were worth in exchange for as little as possible.

If, instead, urban dwellers were treated with respect–provided with basic social safety nets, guaranteed housing standards, access to nice public green spaces, and the like–they would be loyal supporters of the Japanese nation and put their all into accomplishing its goals. And for Seki, that was the endgame, make no mistake; his focus on issues of social class in the big cities led some of his contemporaries to accuse him of Marxist sympathies, but Seki was a Japanese nationalist through and through. He simply saw the urban class as a valuable part of the broader Japanese ‘national destiny.’

So ok, how would the urban classes be brought round and reconciled to that destiny? Basically, through active and engaged policy led by local politicians that emphasized issues of livability–housing, parks, schools, good roads, all that jazz.

To do this, local leaders would need the central government to devolve more decision-making authority to them–where previously, they’d largely been responsible for merely implementing decisions made back in Tokyo by the Home Ministry rather than pre-emptively crafting policy to suit local needs.

In his study of Seki’s views, the American historian Jeffrey Hanes phrases the core of his philosophy well, albeit by making use of some fairly arcane academic language. According to Hanes, most of the Japanese elite–business-owners, urban bureaucrats, and the like, viewed cities as objects in the grammatical sense–a thing to be acted on, to be treated as a mine of resources from which labor or tax money or other things you needed could be extracted, but which were not really valuable beyond that arena. Indeed, cities were literally untrustworthy; Hanes cites the example of the urban planner Yamazaki Rintaro, who visited the US in 1911 and was absolutely scandalized by something he saw in every major city: high-rise apartment buildings. I’ll quote from Hanes here: “Noting ominously that the residents of high-rise housing would be physically distant from the land,Yamazaki argued that they would thus be equally distant from the social fabric of the urban community. Because Basic Values of cooperation and group harmony emanated essentially from Japanese attachment to the soil,he insisted,high-rise living posed a real and present danger to love of country itself.”

Seki, by contrast, wanted cities to be subjects–to act in their own right through local government to shape their surroundings and residents proactively, for the good of both the city itself and the wider nation.

It’s a vision of the power and potential of local government that, in a lot of ways, presaged the reforms that would come after World War II, when a more democratic government did devolve far more power to cities to chart their own futures. Unfortunately, Seki himself would not live to see the postwar; he died of complications from tuberculosis in 1935.

But that’s getting a bit ahead of ourselves; during his tenure, Seki would make Osaka into a test case for his vision of Japan’s urban future, and fight to see the city beautified away from its reputation as an industrial hellscape.

His main focus was on suburbanization–building garden suburb neighborhoods that would be nicely livable in their own right, with parks in every neighborhood and good, walkable areas to enjoy. Those suburbs would be connected to the urban core by large thoroughfares–the most impressive of which was Midosuji, the massive north-south avenue that Seki had widened out in the fashion of a Parisian boulevard to connect the city together. Public transit was also central to this vision, both streetcars and light rail as well as this newfangled invention called the subway.

To accommodate the influx of new workers, the boundaries of the city would be expanded by annexing neighboring villages, opening up new lands for development–which would be developed rationally by means of zoning laws dictating what sorts of things could be built where in order to ensure some separation between quiet residential areas and busy industrial ones.

Urban workers would be offered a stake in this new vision of the city by means of social housing–ideally, housing that could be purchased by said workers, turning them from renters who were exploited by the system into property owners who had an active stake in its maintenance.

And finally, all of this would be paid for by some new taxes and fees primarily targeting the wealthy businesses that had done the best out of the existing order.

Seki’s vision was deeply popular with many in Osaka–it enjoyed the backing of the city’s elected municipal assembly as well as several of the city’s major dailies (including a little daily that had started printing in the city in 1879, by the name of the Asahi Shinbun).

As early as 1917, he’d leveraged that popularity into a series of roles both in Osaka and the Home Ministry itself charting out some of the first urban planning initiatives in Japan’s history. By 1918 he’d produced a report outlining the core ideas of his philosophy–which I’ve only briefly summarized here. If you’re interested in the history of cities, Jeff Hanes’s full book on Seki is worth a read.

Seki worked tirelessly over the subsequent decade and a half to make this vision a reality–but it never really got off the ground. Simply put, Seki’s vision–in many ways because of its sheer ambition–ran into a series of issues almost immediately. The wealthy businesses whose taxes would go up to fund it fought against the idea of seeing their costs go up tooth and nail, and without money many of the garden suburb plans Seki had imagined simply couldn’t get off the ground.

Meanwhile, bureaucrats in the Home Ministry in Tokyo were hesitant to devolve the kind of authority to Seki that he wanted to pursue an independent vision for the city, which made actually pushing through changes to zoning laws or annexations of neighboring areas rather challenging because everything had to be run through several layers of national government bureaucracy first.

Ultimately, Seki was able to make some changes–like the aforementioned widening of Midosuji or the expansion of the city’s parklands. His annexation of neighboring cities led to the so-called “Era of Greater Osaka” in the 1920s and 1930s, when the city expanded its borders outward to encompass ever more area.

He’s even the one credited with first opening up a park around Osaka Castle in 1931, though at that point most of the grounds were still being used as an arsenal by the Imperial Japanese Army.

However, his broader policy reforms never got off the ground–and after the devastation of the war, when Osaka’s population again exploded with workers looking to find jobs in a shattered postwar economy, a chaotic rebuilding process erased much of the careful planning Seki had done to shape the neighborhoods of the city.

He does have a statue in Nakanoshima, across from Osaka’s City Hall, along with a monument dedicated to his vision of making Osaka a better place to live. Unfortunately, his aspirations to make that happen were never achieved as fully as he’d have liked.

Now, I am going to actually wrap the miniseries here, which might seem odd because just under 100 years has passed since Seki’s death in 1935. And of course quite a bit has happened in Osaka since then–the city was leveled in World War II by American bombers (including Osaka castle getting blown up one more time, which seems to be something of a theme) and then rebuilt into its present form. It rose from the ashes of the war to become once again one of the greatest cities in Japan–hosting a worlds fair in 1970 that served a parallel function in some ways to the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo–just as the 64 Olympics were a showcase for postwar Tokyo, the 70 worlds fair was a showcase for a reborn Osaka (complete with a very weird piece of public art called the Tower of the Sun that’s become a bit of a symbol of the city).

All of these moments matter, of course–but in a lot of ways Seki’s story is a better bookend to Osaka’s history, in my view.

The city supposedly founded at the site where the first emperor came ashore to begin his conquests has always, in a lot of ways, been defined by outside pressures. Seki’s attempts to reshape Osaka into a progressive urban paradise–and his mixed record in doing so, largely because of conditions outside of the city itself–mirror the ways in which the people of Osaka have both accommodated themselves to the tides of Japanese history and been subjected to them. Osaka has always been a city defined by its relationship with the rest of the country, and for better or worse that’s the defining aspect of its story–at least as I see it. But that very aspect also makes the history of Osaka valuable for exploring Japan’s own history in a new and exciting light.