Oe Kenzaburo is about as different a writer as you can think of from Kawabata Yasunari, and yet he’s Japan’s second ever Nobel laureate in literature. What sort of concerns defined his work, and what can we learn from looking at him in conjunction with Kawabata?

Sources

Sakurai, Emiko. “Kenzaburo Oe: The Early Years.” World Literature Today 58, No 3 (Summer, 1984)

Oe, Kenzaburo and Sanroku Yoshida. “An Interview With Kenzaburo Oe.” World Literature Today 62, No 3 (Summer, 1988)

Brown, Sidney Devere. “America Through the Eyes of Oe Kenzaburo.” World Literature Today 76, No 1 (Winter, 2002)

Oe, Kenzaubro, Steve Bradbury, Joel Cohn and Rob Wilson. “An Interview with Kenzaburo Oe: The Myth of My Own Village.” Manoa 6, No 1 (Summer, 1994)

Oe’s obituary in the New York Times, and a copy of his Nobel Lecture.

Images

Transcript

In many respects, part of what was exciting for me about this miniseries was the chance to talk about an intriguing generational difference. Kawabata Yasunari was born in 1899, in (depending on how you parse it) either the second or third generation of the new Meiji imperial state. He was born into an era of rising imperial tides, and of a renewed patriotism and passion for things Japanese–a fact that I suspect informed somewhat his interest in a ‘peculiarly Japanese’ literature.

Oe Kenzaburo, on the other hand, was born on January 31, 1935–which meant that he came of age in a very different Japan. His formative years were not defined by a triumphant rise to the heights of the great powers, but by crushing defeat.

Oe was born into a poor family, the fifth of seven children of Oe Kotare and Oe Koseki (counting Kenzaburo) with three brothers and three sisters. The family was from Ose, village that’s now a part of Uchiko township in Ehime Prefecture on the northwest coast of Shikoku.

Ehime, particularly in the early 20th century, was one of the more rural areas of Japan, and Ose was one of the more rural parts of Ehime–. The Oe family had been samurai once upon a time, but had fallen on hard times (in part because of the poverty of the region, and in part because Ehime–the former Matsuyama domain–had been staunchly pro-shogunate in the tail end of the feudal era). Kenzaburo’s father Kotare actually made his living stripping bark from trees to be sold for various commercial uses.

Still, Oe Kenzaburo was able, thanks to the advent of universal education in Japan, to at least go to school–though it was far from the smoothest educational experience, because he entered elementary school at 6 the same year the Pacific War began. Despite that, his education was a fairly standard one, working his way through the city’s elementary, middle, and high schools–the only remarkable thing was that in his second of three years in high school, he transferred to the higher quality public school in the far larger town of Matsuyama, the prefectural capital.

Honestly, it’s pretty neat to see a Nobel laureate produced by a public education system in a rural area. This is why you invest in education!

Apparently, young Kenzaburo developed an interest in storytelling from a young age, driven primarily by his grandmother–who regaled him with tales of her own youth during the very earliest days of imperial Japan, when Ehime was home to a fairly large antigovernment uprising in 1872 (alongside nine other prefectures) opposed to the then-brand-new universal conscription law.

It’s always tempting to read into an author’s future from these childhood anecdotes, and while it’s probably good sense to resist the impulse one can’t help but wonder if Oe Kenzaburo’s own rebellious streak, politically speaking, grew out of those childhood stories.

It’s editorializing, certainly, but it does make for a good story–and I feel like he of all people would appreciate that.

The formative experience of his childhood, he later said, was (of course) the shocking announcement in August of 1945 that Japan had lost World War II. Like all schoolchildren, Oe had been subjected to rigorous classes in “ethics” that were largely exercises in pro-government propaganda. He’d later recall that they were drilled to respond to questions like, “what would you do if the emperor commanded you to die?” with things like, “of course I would cut open my belly.”

Oe would later recall the shocking events of August 15, 1945, when Emperor Hirohito, for the first time, took to the airwaves and read the decision to surrender in his own voice: “The strange and disappointing fact was that the Emperor spoke in a human voice like any ordinary man. Though we couldn’t understand the speech, we heard his voice. One of my friends could even imitate it cleverly. We surrounded him, a boy in soiled shorts who spoke in the Emperor’s voice, and laughed. Our laughter echoed in the summer morning stillness and disappeared into the clear, high sky. An instant later, anxiety tumbled out of the heavens and seized us impious children. We stared at one another in silence.”

Much of his later literary career was an attempt to grapple with the void left by defeat–the collapse of what had been absolute moral certainty in the righteousness of the imperial cause, and the need to figure out what belonged there instead.

Defeat–which came, for those of you counting along, when Oe was 10 years old–also meant that the second half of his pre-university education took place, not under the old regime but under the American Occupation. “Ethics” as a subject was discarded in favor of programs to study the new constitution and the meaning of “democracy.”

And the fact that Oe came of age during that time explains a lot about why so much of his career is bound up with Japan’s politics. He would, for the rest of his life, be a fierce defender of and believer in the postwar constitution. In her work on Oe’s early years, Sakurai Emiko illustrates this nicely by contrasting Oe with Mishima Yukio, who was born just over 10 years before Oe (on January 14, 1925). Thus, he grew up entirely under the prewar militarist regime–and that’s one way to explain the right-wing politics that defined his life.

Initially, Oe apparently wanted to become a scientist before being discouraged by his teachers. However, he was also always interested in literature, particularly poetry; he’s from the same part of Japan as the great haiku poet Masaoka Shiki, and the Matsuyama high school he transferred to was the same one Masaoka had graduated from decades earlier.

Oe’s own brother would actually become a poet focused on traditional Japanese poetry, and later in life Oe would credit his own sense of speech and rhythm in his writing to his youth composing waka poetry.

With Masaoka as his gateway, so to speak, Oe then found his way to more modern Japanese poets like Tominaga Taro and Nakahara Chuya, and from them to French and English poetry–he was a particular fan of WH Auden, the British poet whom Kawabata Yasunari would beat out for a Nobel Prize in 1968.

In literature, Oe’s childhood favorite was apparently a copy of Huckleberry Finn he read during the Occupation years–one of the canonical works of American literature. in particular, Oe was apparently deeply moved by Finn’s decision in the pre-Civil War South not to partner with Jim, a runaway slave, rather than turning him in to the authorities. For a young man who’d been raised to view authority and the obedience thereto as an absolute good, the decision to ignore authority in favor of doing what was right was deeply moving. Indeed, he’d later write an article on American literature where he would hold up Huckleberry Finn as the archetype of an American-style hero.

After graduating from high school, Oe would take the competitive entrance exams for Tokyo University (which, after 1945, lost the ‘imperial from its name’) and was admitted. Unlike Kawabata, he did not pursue Japanese literature as a subject but instead focused on French. He developed a particular interest in Francois Rabelais, a Renaissance-era writer and satirist and a favorite of his mentor at University, Watanabe Kazuo.

And I should note this is another interesting difference between Oe’s literary background and Kawabata’s. Kawabata Yasunari was certainly interested in Western ideas–his thinking was heavily influenced by the modernist movement, as we discussed last week–but he always viewed himself as a primarily Japanese writer drawing from a Japanese tradition (though that tradition was a bit fuzzily defined).

Oe’s literary background and interests were more self-consciously international–in addition to the writers already mentioned, he was apparently also a big fan of Dostoevsky in particular (calling the great Russian writer’s work a cure for his own anxieties and uncertainties).

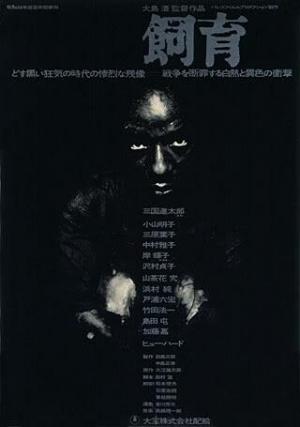

While still in university, Oe began to rise to heights of literary fame, publishing a series of short stories during the final two years of his college education. In 1957, as a senior, he developed a national following when one of his short stories (Shisha no Ogori, or Proud are the Dead) was shortlisted for the coveted Akutagawa prize in literature (losing out narrowly to Kai Kouken, five years his senior and author of “Hadaka no Ousama”, or “The Naked Emperor”). Someone that young even being nominated obviously drew a lot of attention Oe’s way, even more so when, the very next year, another of his stories (Shiiku) won the prize.

From there, Oe’s career took on a meteoric upward trajectory, and the rest, as they say, is history.

However, I don’t think I can bring up that particular story without some mention of what it’s about. We’ve actually discussed it before, way back in our episodes on black history in Japan (episode 347, to be specific). The tale is based loosely on a story Oe was told by his teachers in school, about a black aviator being shot down in rural Japan during WWII. Oe was clearly attempting to make a point about the complexity of race as it relates to American-Japanese relations, for example by having some of the villagers discuss what they’d heard about race in American life. But he also slips into some pretty questionable depictions of the Black pilot, particularly depicting him as obsessed with sex and sexually predatory.

I’d call those questionable choices at best, and to my knowledge Oe himself never really grappled with the portrayal later in his career.

Before we get into Oe’s writing, there’s one other aspect of his life that I want to highlight. Given that Oe was graduating from college in 1958, he was on the older edge of the so-called Anpo Generation: the generation of young students who grew up in the shadow of the Second World War, and who spearheaded the protests against the renewal of the US-Japan Mutual Security treaty in 1960.

Those protests, in turn, were one of the defining moments of postwar Japan. They represented a sort of perfect storm politically; Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke’s decision to renew and revise the security treaty with the United States, which he thought would be largely controversial, turned out to…well, not be. Concerns about being tied to the United States in the Cold War (and thus becoming a target for the Soviet Union) combined with a sense of anger at Kishi’s autocratic handling of dissent around the treaty (forcing its ratification through the Diet with minimal debate) to produce massive protest. The result was a truly incredible series of street protests culminating in a literal battle over the gates of the Diet between protestors and police, in which one of the protestors was killed.

Oe was part of the group of left-wing student activists who had opposed the treaty from the jump. As we’ve discussed before, most of the eventual opposition to the treaty–and the bulk of the protestors–came to the cause driven more than anything by Prime Minister Kishi’s handling of the issue, which was perceived as undemocratic and authoritarian (a sensitive issue given the newness of Japan’s own postwar democracy). Oe, however, was not one of these later comers who was concerned more with how Kishi was doing things than what he was doing. He opposed the treaty from the jump.

Oe was firmly in the camp of Japan’s political left, and was an opponent of the security treaty largely on ideological grounds. He was not particularly unusual among students of his generation in this; in the 1950s, university campuses, dominated by students who grew up during a reaction to the militant rightism of the 1940s, were hotbeds of political leftism. Sidney Brown, who was a research fellow at Tokyo University at the same time Oe was there, relates one anecdote from the time Oe was in school; he recalled a student strike held to protest a British hydrogen bomb test that was so effective the campus was virtually emptied of its thousands of students.

Given the climate of activism on campus, it’s not surprising that Oe was involved in activism during and shortly after his time in school. However, this was not some schooltime fixation of Oe’s that was left behind as he grew older. He’d remain a staunch leftist throughout his life, and in many ways a voice of left-wing dissent in a society that, as he grew older, increasingly was dominated by the center and right.

For example, Oe was a constant critic of the Japanese right; he was an active critic of the whole textbook system imposed by the Education ministry in the mid-1950s to centralize control over how Japanese history was taught in schools. In one interview, given to the New York times in the 1990s, he described the textbooks approved by the government as, “watering down the infliction of damage on other nations and justifying Japan’s invasion and colonial rule.”

He also directly attacked the Japanese extreme right, and especially the fascist movements of the uyoku dantai. For example, in 1961 he produced two short stories based on Otoya Yamaguchi–the right-wing teenage fanatic who, in the summer of 1960, had stabbed the Socialist Party chairman Asanuma Inejiro to death in the middle of a televised debate.

Oe’s story portrays its protagonist–based pretty clearly on Yamaguchi, who committed suicide in his prison cell shortly after the murder–as the product, not of true patriotism, but of socially-alienated teenage masculinity. The protagonist’s story starts off as almost a teen comedy, where he’s just a maladjusted boy making dick jokes with his friend.

The difference is that he discovers meaning, not in the typical teen movie sense of ‘being yourself and loving your friends’ and all that stuff, but in a street battle he’s swept up in between left wing students and right wing counterprotestors. He joins the ultraright and assassinates an unnamed politician based on Asanuma–driven both by a desire to find certainty in his confusing life and by increasingly mad visions of the emperor, an idealized god-like figure who begins to appear to him.

The two chapters of this story, entitled Seventeen and The Death of a Political Youth, had to be withdrawn from publication because of the controversy surrounding them–the magazine that ran them, Bungakai, had to issue a retraction after it was bombarded with threats from right-wing groups, and Oe, fearing for the magazine staff’s safety (and his own) agreed to withdraw the story from circulation.

Less straightforward is the relationship between Oe and the United States–a relationship summed up well by the word ‘ambiguity’, which we’re going to come back to later in the episode. The US, of course, was responsible for the ultimate destruction of Japan’s wartime regime, unleashing the freedom that so defined Oe’s life and career.

On the other hand, I think it is fair to characterize American policy towards Japan as fairly cynical–championing freedom of the press while also banning stories during the Occupation that spoke about the atomic bombs, or championing self-determination while also maintaining Okinawa as a US-controlled territory for military bases until 1972.

In his essay on Oe’s views of the United States, Dr. Sidney Brown refers to Oe as a “friendly critic of America”, and I think that’s a good way to frame it. Oe was not, I think it’s fair to say, anti-American in his politics–and indeed there was much he admired in American ideas around personal independence, responsibility, and freedom. But he was also deeply put off, to say the least, by the substantial gap between the lofty ideals espoused publicly by the US and some of its more self-serving policies overseas, in Asia and elsewhere (and to be fair, he was far from alone in that).

All told, where Kawabata Yasunari attempted to be studiously apolitical (though how successful he was at that is, to say the least, debatable), Oe had no such pretensions. He was very much a child of the Japanese left, including a stint as a college student in the All Japan league of student self-governing associations, or Zengakuren–and joining the 1960 Anpo protests against the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty. Later in the 1960s he was actively involved in everything from the anti-Vietnam War citizens group known as Beheiren to the nuclear disarmament movement to the movement to demand a reversion of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty.

Now, OK, you might be wondering, that’s all well and good–but why does it matter for the story of Oe Kenzaburo as a writer? Well, because just as Kawabata’s studiously apolitical politics informed his work–for good and ill–Oe’s overt embrace of left-wing politics–and the politics of the so-called Anpo generation–informed his.

Obviously 17 and Death of a Political Youth represent examples of this, given how directly they grapple with the nature of right-wing politics in Japan. But even his less well regarded work deals with similar themes–and here, I’m thinking of Oe’s first novel Warewa no Seidai, or Our Generation–which came out in 1958 and was widely panned when it did.

The novel is set in the aftermath of the Occupation, and involves a sort of strange love triangle between Yasuo–a young Japanese man who serves as a sort of stand-in for Oe and other male youth of his generation–Wilson, an American of undefined occupation living in the country, and Yoriko, a sex worker with whom Yasuo has a relationship that slowly fades away in favor of her relationship with Wilson.

The novel was, as already established, not terribly popular when it came out–largely because so much of it revolves around sex, and because Oe wrote the sexual scenes extremely graphically, with a lot of emphasis on sweatiness and…fluids, let’s say.

And in the interest of the Clean tag that I put on this podcast almost 10 years ago, that’s all I’m going to say about that, except to say that I’ve read bits of the scenes in question and yeah, they’re pretty extra.

This was not, however, Oe’s attempt to write smut–indeed, if it was, it’d be pretty bad, because the whole plot is decidedly not very sexy for something that revolves so much about sex. Instead, it’s largely about Yasuo’s insecurities as personified by his loss of his primary sexual partner to Wilson, and how those insecurities are wrapped up in his own insecurities about being Japanese. After all, Yasuo wonders–what does his generation have to look forward to? They can no longer be heroes in the mold of World War II era soldiers, and their country has been forced into a subservient role by America–as personified by Wilson and Yoriko’s relationship.

Oe was pretty clearly attempting to make a point about the nature of postwar Japanese identity–the title itself, Our Generation, being a bit of a giveaway there. As he’d write in a later essay, “The spiritual preoccupation of Japanese youths generally is to wish for exile, for escape from Japan. In fact, many young Japanese already live as exiles within Japan. [For instance,] young Japanese have rejected Japanese films, and they watch foreign films as if they were their own. They come out of the movie theater with the walk and the facial expression of foreigners, reveling in these few moments of escape from their identity as Japanese. What’s more, they try to prolong these moments of bliss as non- Japanese. On the Ginza, as well as at summer resorts such as Karuizawa and Kamakura, the fad to find ways not to be Japanese has become rampant.”

Yasuo’s whole struggle was an attempt to grapple with that desire to ‘not be Japanese’–indeed, the way he ultimately escapes his own doubts is by getting a scholarship to move to France.

Interestingly, like many other members of the Anpo generation, by the late 1960s Oe’s work would move away from themes concerning the Japanese left directly–the US-Japan relationship, for example–and into more of a focus on individualism and self-actualization, more existentialist than political.

In this too, his trajectory mirrored many other members of the Anpo generation, who became increasingly disillusioned with traditional left-wing movements. But for Oe, there was one other, specifically personal catalyst.

In February of 1960, Oe married Itami Yukari, daughter of the early Japanese director and screenwriter Itami Mansaku (and sister of Itami Juzo, whose work as a director we’ve also discussed previously on the podcast).

The two would eventually have three children, but one of those three was of particular relevance to his literary career. Their eldest, child, a son named Hikari, was born in 1963 with a serious condition called brain herniation–essentially, when pressure from the skull pushes the brain in ways it is not supposed to be pushed. The operation to relieve said pressure left Hikari with brain damage that led to both visual impairments and serious developmental delays.

Grappling with what it would mean to raise Hikari became a serious theme of Oe’s later work, most notably his 1964 book A Personal Matter, or Kojinteki na Kaiken. He would return to this theme several more times over the course of his career–and ultimately father and son would be able to find ground together.

Hikari’s parents would find, you see, that their son was soothed by music, and so would play it for him on the regular–and eventually, though language always remained a challenge for him, Hikari would become a composer himself. Today he’s quite highly regarded as one, and apparently father and son would spend a great deal of time together, both creating in their own ways.

Still, it would take time for the two to have that relationship; initially, Oe Kenzaburo would later say he felt overwhelmed by the challenge of raising a son like Hikari, and would essentially flee his family for a time by taking a journalism job on short notice and temporarily abandoning his writing career.

Still, this too proved a fortuitous moment; he was assigned to cover an anti-nuclear conference in Hiroshima, and over the course of his time there was profoundly impressed by the stories of the atomic bomb survivors he met. In particular, Oe would later recall a discussion with Dr. Shigeto Fumio, himself an atomic bomb survivor who had devoted his life to treating those who had survived the blast. Shigeto, Oe recalled, was a man of supreme compassion, who told Oe that, “If there are wounded people, if they are in pain, we must do something for them, try to cure them, even if we seem to have no method.”

The experience was highly formative for Oe, both personally–it steeled him to step up and be a father to his son through difficult times–and politically, because his experience in Hiroshima led him to a belief that Japan’s biggest issue was the nation’s inability to wrestle in its own way with those left behind by the changes wracking the country. He’d later tell the Paris Review that he felt he was a boring person because, “I read a lot of literature, I think about a lot of things, but at the base of it all is Hikari and Hiroshima.”

And that trajectory, Hikari and Hiroshima, would indeed carry much of Oe’s career from this point on. After A Personal Matter–a novel about a father coming to grips with his son’s brain herniation, so pretty on the nose–he’d produce Man’en gannen no futoboru–literally “Football in the Year 1860”, but known in English by the somewhat more poetic A Silent Cry.

This too is a story about a man running from father hood (in this case a vegetative son) who ends up with his brother in their hometown in rural Shikoku. There, he ends up reliving a story from his family’s past, when two siblings found themselves on opposite ends of a peasant uprising in the final years of the shogunate.

There’s also Kaifukusuru Kazoku, or a Healing Family–a nonfiction work about the family’s struggles, with illustrations done by Oe Yukari (who is a very talented artist in her own right).

In terms of Hiroshima, meanwhile–Hiroshima Notes, based on his time in the city, came out in 1965, and the experience spurred an interest in those at the periphery of Japanese society. Okinawa Notes, written five years later on the occasion of the announcement that the islands would revert to Japan from the US, grew out of similar concerns.

Realistically, there’s no way I could cover Oe’s entire oeuvre; he published, by my count, 31 more books after A Personal Matter, not to mention countless interviews and shorter pieces. But I think this gives a good sense of his trajectory–concerned both with the emotional experiences that defined him, and with the broader experiences that defined his generation. He’d later say that he felt the ills of Japanese society stemmed from a sense of complacency–that after about 1970, the ferment of postwar Japan settled into a sort of lazy materialist conformism that ignored the questions of what it meant to be a freeer and more equal ‘post-imperial’ society in favor of simply getting rich, and which pushed those out of the mainstream to the side because of the awkward ways their very presence invited discussion of those difficult topics. As he put it in one interview, “The writer’s task in Japan is to write down his words one by one, with the idea in his mind of a radical rearrangement of the unitary cultural paradigm in his own country, and elsewhere.”

And it was apparently that very radicalism that got the attention of the Nobel committee, who awarded Oe the Prize in Literature in 1994 because he, “with poetic force creates an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today.”

We don’t know as much about his nomination process because of the 50 year requirement around the ballots being kept secret, so we won’t actually know how the nomination and voting went until 2044.

Oe’s acceptance speech, in turn, is probably one of the most famous things he’s ever written–like so much of his work, it’s about the predicaments of modern Japanese society. It’s also a play on the speech given by Japan’s only other Nobel Laureate–Kawabata’s lecture was entitled utsukushii Nihon no Watashi (Japan, the Beautiful, and Myself, or more literally “Myself of Beautiful Japan”). Oe’s, in turn, is called Aimaina Nihon no Watashi–Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself.

Much of the essay, as you might imagine, is in direct reaction to Kawabata, whose view of Japan as “beautiful” Oe says he cannot share. I certainly don’t think I can outwrite the man himself, so I’m just going to rely on his own words here: “As someone living in the present…and sharing bitter memories of the past imprinted on my mind, I cannot utter in unison with Kawabata the phrase ‘Japan, the Beautiful and Myself’…My observation is that after one hundred and twenty years of modernisation since the opening of the country, present-day Japan is split between two opposite poles of ambiguity. I too am living as a writer with this polarisation imprinted on me like a deep scar.

This ambiguity which is so powerful and penetrating that it splits both the state and its people is evident in various ways. The modernisation of Japan has been orientated toward learning from and imitating the West. Yet Japan is situated in Asia and has firmly maintained its traditional culture. The ambiguous orientation of Japan drove the country into the position of an invader in Asia. …What I call Japan’s ‘ambiguity’ in my lecture is a kind of chronic disease that has been prevalent throughout the modern age. Japan’s economic prosperity is not free from it either, accompanied as it is by all kinds of potential dangers in the light of the structure of world economy and environmental conservation. The ‘ambiguity’ in this respect seems to be accelerating. It may be more obvious to the critical eyes of the world at large than to us within the country. At the nadir of the post-war economic poverty we found a resilience to endure it, never losing our hope for recovery. It may sound curious to say so, but we seem to have no less resilience to endure our anxiety about the ominous consequence emerging out of the present prosperity.”

The antidote to that ambiguity, he says, is art–drawing again on the story of his son, for whom music was a way forward toward connection with others. Because art, he says, is all about humanity–both in the literal sense and in the idea of learning compassion and humaneness.

It’s a lovely speech, if a very intellectual one, and well worth a read in my view.

Oe’s final work, In Late Style, was published in 2013. Towards the end of his life, he remained very active in politics–for example, in the 2000s, he was embroiled in a lawsuit with two former Imperial Japanese Army officers who accused him of defamation as a result of Okinawa Notes. Specifically, they took issue with Oe’s (totally historically accurate) claim that Japanese soldiers encouraged and sometimes forced the mass suicides of Okinawan civilians during the battle for the island–Oe would eventually win the lawsuit, but it would prove a very draining experience for him.

He would also remain active in Japan’s antinuclear movement, both in terms of disarmament and, after 3/11 and the Fukushima meltdown, arguing for the shutdown of the nation’s nuclear reactors.

Oe died just a few months ago, on March 3, 2023. These days, he’s not quite the sensation he once was; he himself jokingly noted in an interview in the 1990s that he was not even close to the biggest name in Japanese literature anymore, and that young up and comers like Murakami Haruki and Yoshimoto Banana were outselling his works by a wide margin. Indeed, Oe’s work did not sell particularly well after the 1960s–ironically, several decades before he got the nod as a Nobel Laureate.

Perhaps the cultural conversation had left him behind; or perhaps an author who viewed the basic concerns of modern Japanese society as a myopic avoidance mechanism to get away from confronting the real issues of postwar society is always going to have a hard time marketing himself.

Despite not exactly being a chart topper, I do think Oe’s work does what all literature at least in part aspires to do–it gets at an important part of that cultural conversation. Just as Kawabata Yasunari’s work is all about notions of beauty–and the uncomfortable politics that can sometimes underlie discussions of beauty in a Japanese context–Oe’s really is all about ambiguity. It’s about highlighting the contradictions of a freer Japan that gained that freedom from another country at gunpoint, or about a wealthier and more equal society that continues to push people to the margins if they don’t fit a predetermined image. More intimately, it’s about the ambiguity of embracing or running from responsibilities and relationships when things get tough.

These are, of course, deeply human concerns, but they’re also very much the concerns of Oe’s time and generation. Perhaps that is, in the end, the best way to think of him–as someone who gave a voice to what it meant to grapple with the complexities of life in the new Japan.