This week, we’re starting a look into how an Indian lawyer and judge from a relatively obscure background became a focal point of right-wing Japanese nationalism. Who was Radhabinod Pal, how did he end up a judge in the Tokyo Trials, and what led him to claim that there were no grounds to convict Japan’s leaders of any crime after World War II?

Note: this episode does contain indirect discussion of war crimes. Listener discretion is advised.

Sources

Nakazato, Nariaki. Neonationalist Mythology in Postwar Japan: Pal’s Dissenting Judgment at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Nandy, Ashis. “The Other Within: The Strange Case of Radhabinod Pal’s Judgment on Culpability.” New Literary History 23, No 1 (Winter, 1992).

Ushimura, Kei. “Pal’s ‘Dissenting Judgment’ Reconsidered: Some notes on Postwar Japan’s Responses to the Opinion.” Japan Review 19 (2007).

Images

Transcript

If you make your way to Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, you might notice something odd. Well, ok, in truth you’ll notice a lot of odd things. The shrine, founded in the early Meiji years to commemorate Japan’s war dead, has been an independent entity since the 1945 decree forbidding government support for religious institutions. Today, it’s a hotbed of rightist historical revisionism in Japan; I’ve written about the museum on site, the Yushukan, for our Patreon supporters, and even the grounds themselves make it very clear what kind of place you’re in.

For example, towards the east entrance there’s a monument to the suffering of Japanese nationals imprisoned by the Soviet Union after WWII, which, fair enough–but funnily enough no mention of how all those Japanese nationals happened to be on the Asian mainland at the end of WWII. Funny, that! I guess they just got very lost in Manchuria for several years.

Anywho: tucked in amongst all this, right across from a series of monuments to the dogs, pigeons, and horses who died for Japan (which, I’m not sure they’d see it that way, but whatever), is another monument that might catch your eye. The monument, a simple stone with a photo and some text, is not devoted to a hero of Japan’s military past, but to a judge. And not even to a Japanese one: to an Indian jurist by the name of Radhabinod Pal.

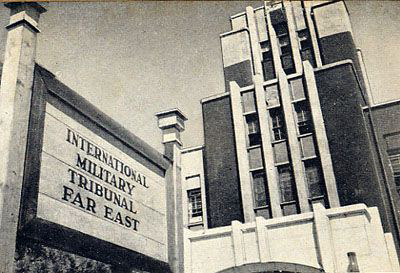

Judge Pal is, of course, famous primarily for one thing: he was one of the judges chosen to help direct the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, and the only one–when it came time for the final judgment–who judged every Japanese defendant to be not guilty.

The Yasukuni monument, which was set up in 2005, was set up in order to (in the Shrine’s own words) honor Pal’s “courage and passion” in making that choice.

Of course, for a place like Yasukuni, it’s not terribly surprising that their politics would lead them to honoring Pal’s choice. What’s more interesting to consider, at least in my view, is why Pal made the decision he did–and how that decision, as embodied in the Yasukuni monument, has become a rallying point for Japan’s right wing.

First, of course, we should talk about the winding road that brought Pal to Tokyo after the war.

He was born on January 27th, 1882 in what was then the British colony of India–today, his hometown of Salimpur is within the borders of Muslim-majority East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) after the Indian partition, but (as was not uncommon in the complex world of pre-partition India) Salimpur was a majority-Hindu village. His parents (Binpihari and Magnakumari Pal) were moderately well off–by caste, they were Kumbhakar, essentially potters, not exactly a high caste but not a particularly low one either. And in the economic turbulence of the times, many Kumbhakar families (including the Pals) had left pottery behind in favor of higher status positions as clerks or secretaries–their wealth as artisans giving them some access to education and the social mobility it provided.

The Pal family, however, did not have an easy go of it; when Radhabinod was only 3, his father Binpihari vanished mysteriously; he’d apparently always been a religiously-minded man and likely abandoned his family to join a religious movement associated with the Vaishnavite Hindu sect that was growing rapidly in Bengal at the time.

Pal (the second of three children, but the only son) and his mother were left to fend for themselves. Indeed, the family was so poor Radhabinod himself almost didn’t end up going to school, except that a local Muslim schoolteacher took pity on him and allowed him to sit in on some classes for free. The boy proved an adept student, and was in short order able to finish the primary school curriculum, apply for scholarships, and then shoot through the academic ranks, culminating in a move to Calcutta–then the capital of British India and the largest city in Bengal–in 1905 to study at Presidency College there.

Initially, Pal’s interest was actually in mathematics, not law. His first few degrees–a bachelors and masters, finished by 1908–were in mathematics, at which he had a substantial talent.

It was actually his mother Magnakumari who pushed him towards the law–raising the young boy alone, and taking up a job as a live in maid in order to help provide for his schooling, she impressed upon him her belief that a career in the law would be the best way for him to rise to the highest social status his caste would allow.

She was inspired in this belief by a personal fascination with the Bengali lawyer Sir Gooroodass Banjeree, who rose in the mid- to late-19th century from a humble, poor family to become one of the foremost lawyers in Calcutta and a judge of its high court. Apparently Magnakumari Pal admired this rags to riches story–Sir Gooroodass had even, like Pal, grown up without a father and with an initial interest in mathematics–so much that she kept a photo of the judge in their home and made her son repeatedly swear to try and live up to his example.

Initially, Pal had taken up as a mathematics instructor after completing his masters, but at his mother’s urging (she literally summoned him home to plead with him on her sickbed) within a few years he returned to school in at Presidency in order to study the law. His mother would not live to see him finish his work–she’d die in 1917, and he would take until 1920 to finish his schooling–but he would live up to her wishes

Upon graduation, he’d end up working in academia rather than in the practice of law itself, taking up a career at Calcutta University’s law college in 1921. He would supplement this with a role as an advocate (lawyer) in Calcutta’s High Court, essentially the equivalent of a federal circuit court in the US (in the case of Calcutta, the most prestigious one in India because of the city’s longtime role as the capital of the British Raj).

Pal would also consult with the British government on legal matters; for example, his background in mathematics and law meant he was chosen to help draft India’s earliest Income Tax laws.

However, Pal was mostly focused on legal theory and lecturing at Calcutta University at this time rather than government service or working in the courts; he actually wouldn’t get his first judicial appointment to Kolkata’s High Court until 1941, and then only as an interrim judge while one of the others was out on personal leave.

And by the way, there’s something important we have to talk about in terms of Pal’s life before we move on. He’s spent, by this point in his career, a lot of time in Calcutta, one of the largest cities on the subcontinent and home to a large number of what Nakazato Nariaki refers to as India’s ‘middle class’–essentially, English-educated upwardly-mobile Indians who served various roles in the colonial government as intermediaries between the British and their subjects. Pal himself had by virtue of his education and job obviously joined this class as well–and the interesting thing about this group is that despite (or even because of) their close relationship to British rule, this social class was also the backbone of Indian nationalist and anti-colonial anti-British movements.

Indeed, when Pal first arrived in Calcutta in 1905, the city was firmly in the middle of the Swadeshi movement, a fierce but ultimately failed social movement rejecting Britain’s partition of Bengal into a predominantly Hindu Western state and a predominantly Muslim eastern one.

The move, which laid the groundwork for the later 1947 partition of India, was clearly a cynical attempt to divide one of the wealthiest regions of India and a hotbed of nationalist sentiment along religious sectarian lines, and thus engage in a bit of divide and rule. It was also totally unprecedented; Bengal had, despite religious differences, been ruled as a single entity since the middle ages.

The Swadeshi movement was ultimately unsuccessful, and it’s unclear how much (if at all) Pal involved himself with it as a student. Both his friends and family would later say he was largely focused on his studies and on making his mother proud above politics. But it would have literally been impossible to miss what was going on.

It’s also worth noting that the Pal family itself had some reason to be mistrustful of the British. Bengal was home to a major cash crop industry in indigo farming, and farmers had been brutally mistreated by the British in hopes of extracting maximum profits from them, leading to several labor disputes and one open rebellion in the mid 1800s. Pal’s own grandfather had been a part-time indigo farmer, and had lost his land in a legal battle with a British absentee landlord–a story that young Radhabinod almost certainly grew up hearing, and which likely did not do much to endear the British to him.

It’s also worth noting that several of Pal’s school associates were active in the Indian nationalist movement, and particularly in its more militant wings. Several of them were or eventually became close allies of Subhas Chandra Bose–indeed, one of Pal’s school friends was Bose’s older brother.

If that name sounds familiar, it’s because Bose would later reject the Indian nationalist movement’s participation on the Allied side of WWII, and would instead accept aid from Imperial Japan and try to set up an independent Indian government allied with the Japanese cause.

To put it simply: Pal clearly had sympathy for the Indian independence movement and for decolonization more generally, as we’re going to see in a bit. It’s fairly indisputable that–as most members of the English-educated Indian ‘middle class’ were–he was highly sympathetic to the idea of Indian independence. It also seems possible–particularly in light of later events–that Pal had at least some ideological sympathy for Subhas Chandra Bose, and thus in turn for Japan.

Nakazato also found that Pal was friendly with Syama Prasad Mookerjee, whose father had been an early supporter of Pal’s career in the judiciary. If you’re unfamiliar with Mookerjee, he was an early figure of a political party called the Hindu Mahasabha, a right wing Indian nationalist party. Hindu Mahasabha, in turn, was part of the broader nexus of right wing Indian nationalist parties that included the Jana Sangh (people’s party) founded by Mookerjee after he left Hindu Mahasabha as well as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a more militant right-wing movement that was the political ‘home’ of the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948. Mookerjee’s Jana Sangh party in particular is one of the forerunners of the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, which governs India under PM Narendra Modi today.

Broadly, it seems clear that Pal felt at least some affinity with the nationalist right in India. The extent of those feelings is hard to prove; I highly recommend Nakazato Nariaki’s excellent book Neonationalist Mythology in Postwar Japan for more on this subject.

And so, at long last, we come to the moment Pal is famous for. Well before the end of the Second World War, there were already some pretty vigorous conversations about what exactly was to be done with the defeated leadership of the Axis powers once the war ended. The general sentiment, particularly as rumors of atrocities by both the Germans and Japanese began to filter out to the publics of the various Allied powers, was that the behavior of the two countries deserved some kind of public rebuke and punishment–but how exactly was that going to work?

This is where we enter the fuzzy arena of international law, a complex topic given that unlike laws within a country, there’s no overarching authority in international law responsible for defining and enforcing what is or is not legal.

The only thing that came close during and after World War II was the increasingly defunct League of Nations and its up and coming successor the United Nations, whose whole role was based on treaties countries had to agree to in order to be bound by–and which they were responsible for enforcing in their borders and could withdraw from at any time.

This is decidedly not how domestic law works; I do not recommend, if you are ever pulled over in a traffic stop, attempting to proclaim that you have withdrawn from the treaty that binds you to speed limits and thus are not liable.

On top of that, there wasn’t really a precedent for punishing military or civilian leaders of defeated opponents–no such punishments had been meted out, for example, to German generals after WWI based on their occupation of Belgium and the violence against civilians that took place there, despite that violence being well documented.

The closest equivalent would probably be the forced exiles of Napoleon Bonaparte, first to Elba and then to St. Helena–but those were undertaken without any sort of formal hearing or trial, and were simply proclaimed by the victorious anti-Bonaparte powers. There was no pretension of the decision being anything other than victor’s justice.

Indeed, some on the Allied side after World War II saw that as the preferable outcome. Winston Churchill, during a meeting between Allied leaders at Yalta in February of 1945, apparently remarked to US President Franklin Roosevelt and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin that he felt the Axis leadership should simply be summarily shot. Interestingly, one of his subordinates–MI5’s head of counterintelligence, Guy Liddell, apparently felt similarly, as he wrote in his diary that he felt any sort of postwar trial of the Axis leadership would be more of a propaganda exercise than a meaningful exercise in justice given the uncertain legal grounds it would operate under. He wrote, “It seems to me that we are just being dragged down to the level of the travesties of justice that have been taking place in the USSR for the past 20 yrs”–a reference to Stalin’s own show trials

Indeed, Stalin wanted trials for the Japanese and German leaders–he told Churchill and Roosevelt very directly that he felt the potential propaganda value was too much to pass up. Roosevelt, meanwhile, remarked that he felt the American people would demand a trial–so that there could be no question about the justice of either the war or punishments meted out to Axis leaders.

And Stalin and Roosevelt carried the day. The result was the first attempt to hold national leaders accountable before an international tribunal, and to define international crimes like genocide on the world stage. This took the form of the International Military Tribunal–the so-called Nuremberg and Tokyo trials.

And I cannot stress enough what a legal novelty the whole idea of this was. The tribunal defined three new categories of international criminality–crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Only the last of these had any conventional basis in legal theory (thanks to the Hague and Geneva Conventions, where the customs around what was and was not acceptable in war were codified by treaty). But even in this case, the tradition had been to hold states accountable for breaches, not specific leaders. And in the case of Japan, things got even messier; Japan had not ratified the 3rd Geneva Convention of 1929, for example, which dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war. The Imperial Army and Navy did have protocols against the mistreatment of prisoners (protocols that were constantly violated throughout the Second World War), but did the victorious allies have jurisdiction to prosecute those violations?

Crimes against the peace and crimes against humanity, meanwhile, were even thornier. The former was defined as, in essence, criminal conspiracy to commit aggressive warfare–and it was true that Japan, for example, had signed a treaty renouncing aggressive war in 1928 (the so-called Kellogg-Briand Pact). But can you really prosecute world leaders from other countries for violating a treaty? That’s not usually how these things work.

Crimes against humanity, meanwhile, were even trickier to define–the current definition of them, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, wasn’t even solidified until 1998. Broadly, these were acts that violated norms around justice so egregiously that those who committed them had to be made an example of.

These are all, of course, complex legal questions. The negotiations over how to frame responses on the part of the allies–and how to set up the courts themselves–almost ended up spiking the whole trial process before it began.

The history of those discussions is absolutely fascinating, but we don’t really have room for them here given our focus on Pal specifically. The question of the legitimacy of the trials, however, is one that we will return to later–indeed, the question of international law and jurisdiction over those who violate it, remains very much alive today.

Ultimately, the Allies did agree to a format for a trial. That format, first established for the Nuremberg trials and then ported over to Japan, involved a charter establishing an international court composed of representatives of the Allied countries that had faced German (or Japanese) aggression. In Europe, this was the ‘big four’–the US, UK, France, and Soviet Union–where in Asia, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, China, the Netherlands, the Philippines, and, of course, the newly established Indian Republic were all included as well. That means 11 participating countries in the Tokyo Trials.

The move to 11, incidentally, was a pretty fraught political one; in the initial drafts of the Tokyo trial charter, drawn up in 1945, there were only 9 countries (excluding India and the Philippines) on the list of participating powers. It was Great Britain which pushed to include India; at the time, it was hoped that India’s growing nationalist movement could be persuaded to accept Dominion status within the British Empire (similar to Canada and Australia) rather than total independence. The hope was that treating India as one of the victorious powers would help develop more pro-British sentiment in India (it did not).

The US objected to this on the grounds that more judges increased the likelihood of a split verdict (politically undesirable given the novelty of the whole idea). Eventually, a compromise was reached to include the Philippines (a US colony also on the road to independence) as well.

Each participating country would get a chance to contribute to the indictment and prosecution of defendants from the leadership of the two countries, and each, of course, would have a chance to nominate judges to oversee the trial. Given the complications around defining a ‘jury of peers’ in this context, the trials would not be jury trials. Instead, the judges would render verdicts.

Radhabinod Pal was, of course, the choice to represent India at the trial. There’s two consistent myths around Pal’s selection, both of which are commonly replicated by Japanese right-wing nationalists today. The first is that Pal was an eminent and respected judge chosen personally by India’s first independent prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, for this job. The second is that he had a particular–and in some versions, even unique–academic knowledge of international law, making him particularly suited to the task ahead. The first of these is simply an untrue fabrication–the second is an understandable misinterpretation of the facts at hand.

To deal with this latter objection first; the claim that Pal had a special background in international law is based on the fact that he was the 1938 recipient of the endowed position of Rabindranath Tagore professor of international law at Calcutta University, essentially an academic prize which gave the recipient an award of money in exchange for delivering a series of lectures on topics related to international law. However, due to the unsettled situation in India due to both nationalist issues and the leadup to WWII, the 1938 prize wasn’t actually handed out until 1942, and Pal himself didn’t have a chance to complete the lectures (because he was serving on Calcutta’s high court, and then in Tokyo) until 1951. So by the time he did give those lectures on international law for 1938, the Tokyo Trials had already happened.

As for the former objection, just off the bat Pal offered to take the job in Tokyo on April 24, 1946–which means there’s no way Jawaharlal Nehru could have given it to him. India didn’t become independent until 1947, and even the interim pre-independence government set up by the British wasn’t organized until August of 1946. Nehru was not involved at all–and actually was not a fan of Pal’s, for reasons we’ll get into.

The British were the ones that picked him, and then only because their first two choices from India refused to go. The trials were scheduled to start in May, 1946; by April, the British were desperate, and the Americans were threatening to just go ahead and start without an Indian judge. On April 23, 1946, the British leadership–deseperate for someone to fill the seat–cabled the high courts of Bombay, Madras, Lahore and Calcutta asking for a judge to take on the job. Pal was selected for the absolutely incredible reason that he cabled his willingness to go on April 24 and was accepted by the desperate British immediately.

By this point, Pal had served as an interim judge in Calcutta for a total of two years and two months, presiding over just over 60 cases in total (of which only a single digit number were criminal cases). He was an experienced legal theorist, but not an experienced trial judge. And he was not the only one who volunteered; the day after he accepted, the Lahore court responded that one of their judges, Muhammad Munir (the future chief justice of the supreme court of Pakistan) was willing. But Munir was a day late; the British needed someone now and had already taken Pal.

We’re not going to recap the entire Tokyo Trials here–I think they’re interesting if you have a fascination for the theory of international law, given that alongside the Nuremberg Trials they essentially invented international criminal law as a concept–but there’s also a LOT of material to cover. Only 27 leaders faced 55 separate charges before the trial process itself came to a halt, and even in that limited form, I don’t think we need to go through it for this story to make sense.

Because what people remember about Radhabinod Pal’s time as a justice of the Tokyo Trials has nothing to do with the trials themselves, but instead their aftermath–the verdict of the judges.

Early in the process of the trial, the selected judges–led by William Webb of Australia–had agreed to a pledge not to publish separate opinions and to keep their own views on the outcome confidential once the judgment had been issued in order to avoid politicization of their deliberations. Pal did not arrive until after this discussion had concluded, however, and refused to agree to those terms.

Indeed, he largely kept apart from the other judges, and rarely even left his hotel room in Tokyo’s imperial hotel–the only one with whom he had any sort of relationship was Bert Rolling, the judge from the Netherlands. A few of the others, most notably Webb, began to suspect that Pal hoped deliberately to torpedo any attempt at a guilty verdict from the jump–though it’s unlikely, given the frantic circumstances of his appointment, he came with any predetermined plan at all.

In the end, Pal did end up writing a dissenting opinion from the other judges–not the only one, because once he did it several others decided the floodgates were open to do so as well. But his is by far the best known, partially because of its length–it weighs in at over 1230 pages. Its content is also quite provocative, and here I’ll just turn it over to his words: “I hold that each and every one of the accused must be found not guilty of each and every one of the charges in the indictment and should be acquitted of all of those charges…as a judicial tribunal we cannot behave in any manner which maj justify the feeling that the setting up of the tribunal was only for the attainment of an objective which was essentially political…the name of Justice should not be allowed to be invoked only for the prolongation of the pursuit of vindictive retaliation.”

That text in and of itself makes Pal’s core argument pretty clear–that the trial was essentially political theory designed to dress up retaliation by the Allies against defeated foes as justice. Based on the evidence available to us, it’s fairly clear that Pal had made up his mind to write the dissent as early as June of 1946 (so one month into his tenure) and had begun writing it as early as the next month thereafter. So he invested a lot of time and energy into this project.

Pal drove this point home further with a quotation: “When time shall have softened passion and prejudice, when Reason shall have stripped the mask from misrepresentation, then Justice, holding evenly her scales, will require much of past censure and praise to change places.”

If you’re wondering who that’s from, it’s a line attributed to noted traitor to the United States Jefferson Davis defending the record of the Confederate States of America–and I have to say that personally, my past censure on him has not changed overmuch. Maybe don’t commit treason in the name of racism buddy.

But of course, you can’t sum up a 1200 page document quite that cleanly, and Pal had a few subsidiary points to make to support his argument. A good many were jurisdictional, derived from those objections to the legitimacy of the trials we discussed earlier. In addition, Pal accused the trial of having fabricated, in essence, a series of ex post facto laws against which to judge Japanese leaders.

That’s a very fancy Latin term which roughly means ‘after the fact’; an ex post facto law is one that creates a category of illegality that is then retroactively applied to before the law was in effect. This type of law is banned in most countries around the world; Article 1 Section 9 Clause 3 of the US constitution directly outlaws the practice, for example. Pal’s claim, in essence, was that this was what the tribunal had done–its standards of criminality had not existed before the end of World War II, and thus could not reasonably be applied to Japanese leaders after the fact.

To use somewhat fancy lawyer language, Pal is arguing in essence for legal positivism, in essence the view that law can only derive its legitimacy from other law–as opposed to some other, higher source like morality or the greater good or anything like that. In this point of view, according to Pal, you can’t hold Japanese leaders responsible for something that wasn’t technically illegal at the time they did it, even if you think doing so is in accordance with a higher principle of morality.

It’s worth noting that this is not an uncontroversial legal position–and indeed, there are some pretty famous legal positivists, like Hans Kelsen and HLA Hart, who have accepted that ex post facto laws are necessary in some cases. Kelsen, for example, wrote in 1945 about the issue of war tribunals that, “if…the act was at the moment of its performance, morally, although not legally wrong, a law attaching ex post facto a sanction to the act is retrospective only from a legal, not from a moral point of view. Such a law is not contrary to the moral idea which is at the basis of the principle in question.”

Hart, meanwhile, went on the record in a public debate saying that laws can be too evil to be obeyed, and suggested that ex post facto civil suits (in his case, against Nazi informants who had followed the law but violated morality) should be allowed.

Related to this was the claim that the trials themselves represented a form of victor’s justice, because–in Pal’s view–some of the actions of the Allied powers also fit the bill of war crimes as they’d been defined in Tokyo. Most notable in this regard were, of course, the two atomic bombs, as well as the wider Allied firebombing campaign against Japan, which destroyed 60% of the country’s urban area and killed hundreds of thousands of people. Indeed, the firebombing of Tokyo alone killed more people than the atomic bombs themselves.

One is reminded of the utterance of General Curtis “Bombs Away” LeMay (yes that was his actual nickname), architect of said firebombing campaign, who remarked after the fact that had the Americans lost he would never have escaped trial as a war criminal.

This is all true, of course– but it’s also what’s known as a tu quoque, essentially an accusation of hypocrisy. It’s fundamentally a fallacious argument–because of course, the suggestion that America or the other Allies did things that were wrong during the war does not automatically mean that it was ok for Japan also to do wrong things.

Wrapped up in all of this was a far deeper sympathy for Japan’s motives than basically any other justice at the trial. Pal pointed out the claim made by Japan’s wartime government that the conflict was essentially anticolonial–that Japan was fighting a war to liberate Asia from European colonies in the name of Pan-Asian unity.

This is where I think we have to factor Pal’s own history into play; he was very much an Indian nationalist, and again likely had sympathy for the Japanese because of the military and financial support that the Imperial government had provided to the anti-British agitator Subhas Chandra Bose. Indeed, while a great many Indian soldiers and civilians did die in the fight against Japan, proportionate to the subcontinent’s massive population the number directly affected was comparatively small–especially relative to things like the Bengal famine of 1943, which at a minimum killed just south of a million people and possibly a great many more, and which was (not unjustifiably) blamed on British hesitancy to distribute food aid in the area.

It’s also worth noting that Japan had long held a place of, if not pride, at least interest for anticolonial nationalists around the world–including India. Indeed, when Pal had been growing up in Bengal there had been massive celebrations at the announcement of Japan’s victory over Czarist Russia in 1905 as a massive victory for anticolonial movements in general.

Now, it is also important to note one thing Pal did NOT do in his dissent. He did not definitively ‘absolve’ Japan of wrongdoing during the war years or suggest that Japan had been the ‘good guys’ of the conflict. Indeed, he pretty clearly acknowledged the crimes of the Japanese military during the war, referring to them both as ‘atrocities’ and with adjectives like ‘devilish and fiendish.’

His argument, instead, was that these were the responsibility of specific field commanders in the Japanese military–that there was not, as in the case of Nazi Germany, a directive from on high ordering the extermination of civilians. There was not, to put it another way, an organized attempt at a “final solution to the Chinese question” aimed at their total destruction, where the Nazis had made the mass murder of Jews a pretty clear policy from the highest levels of power.

Thus, he said, political leaders on the non-military side of the Japanese government could not be held accountable for those crimes–they had not, in the end, ordered the Japanese military to commit them.

There is something to that objection, though I do not agree with it entirely. This was actually something I’d planned to focus on in my dissertation before funding woes and a general desire to have insurance and a real salary drove me out of academia. Japanese war crimes were primarily the result of a culture within the officer corps of the military that considered civilians of minimal to no importance relative to field objectives, and to whom thus anything could be done if doing so could be convincingly argued to advance the military’s own goals–in resources, in ‘compliance’, or whatever else.

This is not, to be clear, a suggestion that the crimes of the Japanese military were somehow not serious or horrific. They were and are morally reprehensible. That policy is simply a different one from the Nazi view that Jews were their fundamental enemy and that destroying them was an end in itself rather than a means to future military goals.

I don’t agree, however, with the suggestion that this absolves Japan’s leadership, military or civilian, of the decisions made in the field. For better or worse, if you are part of a country’s political leadership, part of what that means is taking responsibility for government decisions. There’s plenty to say about the poor structure of the prewar Japanese government and how it served to diffuse responsibility for all decisionmaking because of the lack of clarity around who actually had the power to make decisions–but that too is a choice that Japanese leaders are morally accountable for. And frankly, the scale and consistency of Japan’s attacks on civilians and its mistreatment of POWs during the war years make it very hard to believe leadership was totally unaware of what was going on–Pal repeatedly an uncritically accepted the assertion that they were.

This is particularly glaring in his evaluation of the 1931 Manchurian Incident–where Pal simply accepted the assertion by military leaders that Japanese interests in the area had been attacked and the army acted defensively. It’s fairly clear from the historical record that this was not the case, and that the whole incident was manufactured by the Japanese military as an excuse for an invasion.

It’s probably most glaring in his discussion of the Nanjing Massacre of 1937, where Japanese forces committed six weeks of atrocities after taking China’s capital city. Pal admitted, again, that the massacre had taken place, but claimed he couldn’t shake the feeling that the primary witnesses who testified on it at the trial–Xu Chuanying and John Gilespee Magee–had engaged in “distortions and exaggerations.”

On what grounds did he feel this? Well, having read the relevant section of the judgment myself, it’s mostly him calling into question the recollections of rape victims–Pal at one point even hesitates to confirm that these were rapes, refering to them instead as ‘misbehavior.’ He does not deal, that I saw, substantially with other kinds of violence.

One finds it hard to shake the view that Pal’s whole argument represents a predetermined stand–a view he’d taken before even considering the evidence, and one that straightforwardly agreed with the claims of the Japanese government that it was fighting an anti-colonial war.

Any evidence that didn’t fit this–the Nanjing massacre, for example, or the fact that other Asians in Korea, China, and Taiwan resisted Japan–was rejected out of hand. Pal actually wrote in his dissent at one point that China was a failed state in the 1930s because of its civil war and thus had no right to defend itself–and that Japan had a right to intervene there to secure its own interests in defeating communist movements. This is particularly ironic because that exact position had been used, of course, by many Western empires to support their own penetration of Asia and other parts of the world.

This either did not occur to or did not bother the man; it’s hard to know his motives, of course, but it really does look for all the world like he was more invested in morally undercutting the Allied cause and standing up to the self-righteousness of the British and other Allied powers than in a calculated assessment of the war years.

Regardless, Pal was in the minority–his dissent might be long, but it had no legal force. And yet it would survive, and gain influence, well beyond its initial publication–and that, and the long shadow Pal casts over postwar Japan, is what we’ll get to next week.

Hi Isaac,

I’m just letting you know that this episode is misnumbered and now there are two episodes 483 (this one and the one about Oe Kenzaburo).