This week: Hatoyama Ichiro’s revenge tour culminates in finally reaching the top spot as PM and in the formation of the LDP. What does the torturous road it took to get there tell us about the man, and about the politics of his time?

Sources

Itoh, Mayumi. The Hatoyama Dynasty: Japanese Political Leadership Through the Generations.

Kapur, Nick. Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise After Anpo

Curtis, Gerald L. The Logic of Japanese Politics: Leaders, Institutions, and the Limits of Change

Some coverage from Deseret News of the declassification of information about the Hattori coup.

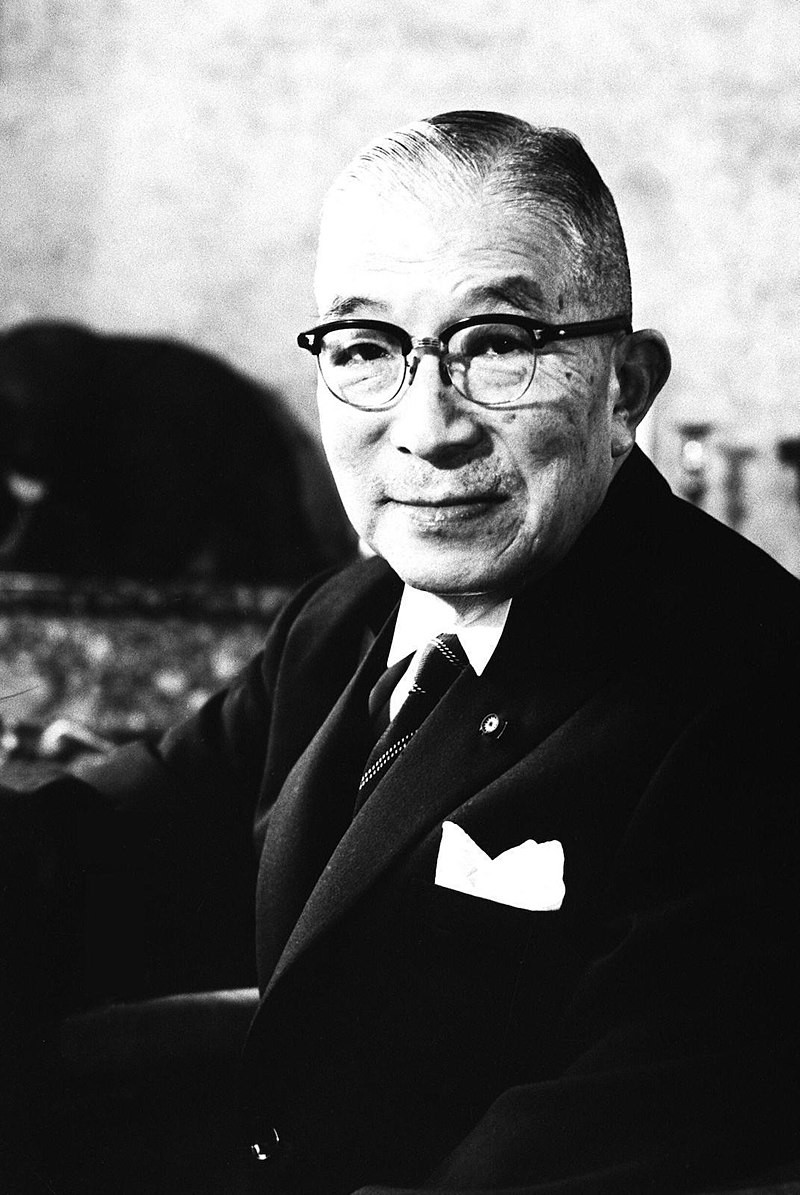

Images

Transcript

One has to imagine that being purged from office was one hell of a shock for Hatoyama Ichiro. The original purge directive announced on January 4, 1946 by the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers, the US Occupation government in post-WWII Japan, did not contain any designations for purge targets that would seem to apply to Hatoyama. It banned from public office anyone directly associated with the army or navy leadership, with Japan’s overseas colonial affairs, and with the host of wartime political and economic agencies and extra-governmental right wing societies which had directed the war effort. Hatoyama had not been a part of any of those groups, and thus assumed he would not be targeted.

Indeed, the decision to purge him came after a very tangled series of discussions, which is why it was announced five months after the initial purge directive. Much ink has been spilled as to why the SCAP occupation authorities decided to bar Hatoyama from politics–ultimately, it comes down to a few key reasons.

First, it’s important to remember that Asia looked very different in 1946 than it would just a few years later. The assumption among American leaders was still that wartime ally the Republic of China would be the main American ally in Asia going forward into what was looking more and more like a Cold War with the Soviet Union. As a result, there wasn’t as much urgency to get Japan ‘up and running’ so to speak, and thus more of a willingness to go after anyone even remotely associated with the wartime regime.

It also, somewhat quizzically, hurt Hatoyama that he had the support of many old American “Japan Hands” who had spent time in the country before the war, most notably former US Ambassador to Japan Joseph Grew. Grew in particular was a big booster of Hatoyama’s–but “Japan Hands” like Grew were also on the outs among many of the leading figures of the Occupation.

The Occupation leadership was made up primarily of either wartime veterans (most notably the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers himself, General Douglass MacArthur) or New Deal democrats from the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. Both groups shared among them an assumption that militarism and ultranationalism was extremely pervasive in Japanese society, and that extreme measures were needed to root it out. In that atmosphere, guys like Grew were perceived as “soft” and too attached to the old ways of doing things in Japan–and thus, his endorsement was an active hindrance for Hatoyama.

The other factor at play was that Occupation leaders were well aware that if Hatoyama was removed from the equation, Yoshida Shigeru would be his natural successor. Hatoyama was perceived by occupation authorities as a party leader of the old school; his politics, they worried, were reliant on oyabun-kobun relationships and devoid of actual ideology.

If you don’t know these terms, they literally mean something like ‘parent’ and ‘child’, but actually describe what amounts to a fictional kin relationship–one where two participants willingly take on the hierarchy implicit in those two terms, with the oyabun leading and the kobun following. Much anthropological ink has been spilled trying to define this subject with more specificity, but I think that serves alright for our purposes.

And to be fair, it’s not beyond the pale to say that Hatoyama Ichiro was a practitioner of that system. Most Japanese politicians were and frankly still are; personal patronage and personal relationships are central to politics in Japan, particularly within liberal political parties.

Because Yoshida Shigeru, meanwhile, had not been a politician before the war–he had been a foreign ministry diplomat and bureaucrat–he was perceived as a more genuinely ideological liberal whose ascent might move the Liberal Party away from that purely relationship-based politics.

This was a major goal for occupation authorities, because remember–Liberalism as an ideology is essentially the small government individual liberties-oriented politics of the United States. So the Liberal Party, as the largest liberal party, would be an essential counterweight to the growing influence of progressive and far left parties like the Socialists and Communists.

Frankly, I do think the accusation that Hatoyama Ichiro was not a genuine liberal in his politics was unfair. His decision to serve in those early 1930s unity cabinets was not a good choice–in my view, at least, it did help launder the actions of wartime militarists–but I can certainly see why someone might choose to have some political access and do what they can instead of the principled “take your ball and go home” approach.

Ultimately, the final tipping point was the leadup to the April, 1946 general elections–where a confident Hatoyama openly and repeatedly attacked the legitimacy of the Communist Party, which was running in the elections for the first time ever (it won 5 seats out of 468). Those attacks were seen in turn as proof of a lack of genuine liberal conviction on Hatoyama’s part–since, of course, a key component of liberalism is a toleration of political dissent, and since this was still early days in the postwar era and the Cold War had not yet really begun to heat up.

And so Hatoyama Ichiro got the boot from office–according to his personal aide Ando Masazumi, when he got the news on May 4 (as he was in the midst of negotiating forming his cabinet) he was pretty devastated, but launched immediately into a plan to have Yoshida step into his shoes. He then required to a quiet life in the family mansion in Tokyo’s Otowa neighborhood, which to be fair isn’t exactly the most tragic possible outcome for him.

However, Hatoyama Ichiro was not, it turned out, done with politics.

The victory of the Chinese Communist Party in the Chinese Civil War–and the growing tensions of the Cold War by the late 1940s–led to a renewed sense of urgency among SCAP leaders. Suddenly, China was no longer available as the main US ally in Asia–Japan was going to have to be it instead, which meant turning the still faltering postwar economy around as quickly as possible and securing the position of a pro-US government.

Yoshida Shigeru was also proving to have some trouble with that. When the new American-written constitution went into effect in early 1947, new general elections were held to fill out the Diet under the new electoral rules–and Yoshida’s Liberals got shellacked, losing badly to the socialists and leading to the first ever socialist Prime Minister in Japanese history (Katayama Tetsu).

Katayama turned out to not be a particularly adept politician, and his cabinet only lasted eight months before resigning–and when new general elections were held in 1949, the socialists lost 2/3rds of their over 150 seats in the House of Representatives.

Still, one imagines that moment was a bit frightening to American occupation leaders facing the specter of a potentially pro-Soviet government in Tokyo.

We’ve talked before about the reverse course–the general move of American Occupation leaders starting in 1947 away from the liberalization of Japanese politics and society, and towards a position that openly favored pro-American conservative political parties and went after bastions of pro-left politics like labor unions. That reverse course also extended to the purges, many of which were walked back in favor of bringing in experienced politicians and leaders from the prewar era whose expertise would (it was hoped) help stave off the political left in Japan.

It’s also worth noting that while SCAP had its doubts about Hatoyama, it was merely one representative of American interests in Japan. Others, like the United States Secretary of State for then president Truman John Foster Dulles, saw Hatoyama as a valuable potential political ally for the US given both his strident anticommunism and liberal bonafides. In particular, Hatoyama Ichiro differed from SCAP’s preferred liberal Yoshida Shigeru in one key way. Yoshida had embraced the idea of Article 9, the part of the 1947 American-written constitution that barred Japan from building a military.

Admittedly, he did not do this because he was a peacenik; Yoshida saw a military as an unnecessary drain on economic resources that had to be directed fully towards the nation’s rebuilding.

Hatoyama Ichiro, however, was strongly opposed to article 9. He was very convinced that Japan needed a military simply because having one was necessary for any country to defend itself in a hostile world–in addition, his ideological opposition to communism led him to concerns about a potential attack on Japan by China or the Soviet Union, and to the idea that Japan needed a strong military to serve as a useful ally to the US in a unified anti-communist front in Asia.

Ideas like this were right up Dulles’s alley, particularly once the advent of the Korean war in the summer of 1950 put some more urgency into the idea of an Asian front against communism. As early as the new year of 1951, he and other more aggressive Cold Warriors in the US government were pushing for Hatoyama’s purge to be re-examined. He also met with Hatoyama a few times to discuss policy–apparently, he considered Hatoyama a valuable political ally and a potential future Prime Minister.

It took until the summer of 1951 for things to go through, but on August 5, 1951, Hatoyama’s name was officially removed from the list of purged politicians.

In the interrim, he’d suffered a pretty extreme setback, both in terms of his political career–because he’d lost control of the Jiyuto he’d helped found–and personally. In June, 1951, Hatoyama was in the midst of intense discussions with two of his aides (Miki Bukichi and Ando Masazumi) about political strategy. These two men represented his closest political allies; both of them were graduates of Waseda University, where of course Ichiro’s own father Hatoyama Kazuo had been president and one of the instructors back in the early years of the 20th century. That personal relationship led both men to be among Ichiro’s diehard followers.

Chiefly, they were discussing what to do about Yoshida Shigeru, who had taken over the Jiyuto in Hatoyama’s absence. All three men suspected–not without reason–that Yoshida had tried to delay Hatoyama’s depurging in order to avoid a potential rival for power (and a potential threat to his Article 9 strategy).

Apparently the discussion–which centered on whether to join the Jiyuto and try to oust Yoshida from leadership or form their own party and challenge him–was pretty intense. Midway through, Hatoyama went to use the bathroom, and while he was there he suffered a stroke.

There was no damage to his ability to speak or to his brain, but his left leg and hand were paralyzed, and Hatoyama was forced to undergo substantial physical therapy to recover. He would later blame the event on his stress levels around the return to politics.

The stroke, in conjunction with plans the very next month for the San Francisco peace conference–the signing of Japan’s final peace treaty with the US and American-aligned allies–in turn served as an excuse for Prime Minister Yoshida, who rebuffed suggestions that he return the presidency of the Jiyuto to Hatoyama on the grounds that he, “could not give power to a sick man.”

And that, in turn, led to splits within the Liberal Party. For a time, the facade of unity was maintained–but by August of 1952, a Hatoyama/Yoshida split within the Liberal Party was clearly visible. In that month, which was to be the start of a new session of the Diet, Yoshida acted as if all was normal–and then, as part of a plan unknown to all but his closest aides, suddenly called for the dissolution of the House of Representatives and for new elections 3 days into the session. Yoshida would later blame the decision to call the election on Hatoyama’s partisans, who he claimed were causing trouble within the Liberal party and making it hard for him to govern–Hatoyama, in turn, would claim that Yoshida called the election by surprise in order to sabotage him, since Yoshida had known it would happen and had already begun to plan an electoral strategy.

The result was an absolutely bizarre election–Yoshida and Hatoyama spent more time attacking each other than their political opponents, while also firmly denying that the Liberal Party was about to split into two separate parties along pro-Yoshida and pro-Hatoyama lines.

The Liberals did hang on to a majority when the ballots were cast on October 1, 1952–but lost 48 seats. And the fundamental tension between Hatoyama and Yoshida was still there–waiting to burst back to the surface.

The two would spar back and forth across 1953. In February–just five months after the last elections–Yoshida was forced to once again dissolve the House of Representatives and call for a new round of voting. The impetus this time was when Yoshida, normally a fairly cool man, lost his calm during a question and answer session with the Diet and called a socialist MP a bakayaro–a moron. Japan, like the US, has rules of procedure that ban insults within the legislature, and so the socialists immediately attempted to censure the Prime Minister (basically calling a vote to condemn him) and talking about a no-confidence vote that would remove him from office.

Yoshida was forced to call new elections to head this off–and when he did, Hatoyama finally struck. Alongside about 50 Liberal Party MPs, he quit the party to contest the election separately. He didn’t do well–picking up just 35 seats to the Jiyuto’s 199, but both parties were clearly on a downward trend and losing ground relative to the two socialist parties (the left and right socialists, who together picked up about 20 seats).

After the defeat, Hatoyama would eventually come back to the Jiyuto, seemingly accepting that Yoshida had beat him politically by not even pushing that hard for any of his own followers to be included in Yoshida’s cabinet.

Except, he hadn’t. Even as Yoshida appeared ascendant in 1954, Hatoyama Ichiro was building a coalition of his own backers within the Liberal Party. In November, 1954, Hatoyama once again quit the party, taking a total of 35 Dietmembers with him. He’d been in secret negotiations with other renegades from the Liberal Party as well as a faction of the more centrist Progressive Party–together, these factions came together into the Minshuto, or Democratic Party.

Hatoyama was not alone in arranging this, to be clear–one of the major actors was a young Liberal Party politician who shared a lot of Hatoyama’s political views (especially around rearmament) by the name of Kishi Nobusuke. But Hatoyama was still the man they picked to lead this new party–which promptly pounced on Yoshida (by this point deeply unpopular, and mired in a corruption scandal in his cabinet) by proposing a no confidence vote and yet another round of new elections.

It is a mark of how unpopular Yoshida was by this point that even the socialists in the Diet were fed up enough with him to work with the anticommunist Hatoyama–with their help, the no confidence vote passed, and in the subsequent general election on February 27, 1955 Hatoyama’s Democrats absolutely creamed Yoshida’s liberals, 185 seats to 114.

Hatoyama Ichiro finally fulfilled his dream; on December 10, 1954, as Yoshida’s government was collapsing in the run-up to new elections, Hatoyama was able to convince a coalition of lawmakers to put him in charge as a caretaker PM before the elections. And once his Democrats grabbed such a large number of seats, he was able to form a coalition to hold on to the PM’s spot.

That coalition, admittedly, was a bit of a mess–185 seats was a lot, but it was short of the 234 needed for a majority (and thus control of the government). Hatoyama was thus forced to cut a coalition deal to start with. Obviously, Yoshida’s Liberals were not that interested (most of them considered Hatoyama a traitor, having backstabbed Yoshida twice in their view). His only other option was the two socialist parties (the left and right socialists), who respectively held 89 and 67 seats.

This was not what you’d call a particularly stable situation politically–the heavily anticommunist Hatoyama in coalition with the communist-adjacent (and Soviet-sympathizing) socialists. And that odd coupling–which made it hard for Hatoyama to actually do much as a prime minister, since he was always at risk of losing the coalition and falling from power–combined with rumors that the two socialist parties were talking about a merger to challenge Hatoyama’s democrats in the next election, led to the first of three major political moments associated with Hatoyama’s prime ministership.

That moment is, of course, the merger of the conservative parties into a single monolithic force. I think it’s fair to say this is one of the biggest moment in the history of Japan’s electoral system, given how dominant the conservatives have been in more or less every election since.

But it was far from a foregone conclusion. Hatoyama’s Democratic Party was pretty much at the throat of the only other conservative party in the Diet–the Liberals. After his humiliating defeat in the 55 general election, Yoshida had resigned from party leadership (a classic response of a party president to defeat in an election), and handed over the party to Ogata Taketora. However, there was still a strong wing of pro-Yoshida sentiment in the party, and certainly a lot of strong anti-Hatoyama feeling as well given how things had shaken out. Indeed, the early months of Hatoyama’s premiership were apparently miserable, because Yoshida’s liberals took revenge against him by constantly summoning him before the two houses of the Diet (the house of representatives and house of councilors).

Both houses have the ability to summon the Prime Minister to answer their questions, and the Liberals in both houses–at this point, the Diet had no formal system for question time, as this process is called, and so it could be demanded by legislators at any moment in both full session and in committees.

Eventually, it became conventional practice to summon bureaucrats rather than the PM to answer the Diet’s questions (because otherwise it was impossible to get anything done), and in 1999 Japan introduced a formal question time system for the PM on a set schedule. However, both of those changes were a long way away in spring, 1955.

The Liberals would constantly barrage Hatoyama with questions, at some points holding him from 10am until 10pm with only one 30 minute break and no chance to do things like go get a drink of water. Hatoyama apparently speculated among his friends that they hoped he would die from the physical stress given his already weakened health.

That gives you some idea of the vehemence with which the two parties were going at each other, but there were some in both parties (including Hatoyama himself) who also felt a merger was not only a good idea but functionally a necessity.

First, of course, there was the threat from the socialist party; if the two wings of the socialist movement merged, they’d be just a few dozen seats short of where the Democrats were at, and if they coordinated candidates instead of competing with each other and pillaging votes then they had a real shot at picking up more.

That was particularly true because at that time, seats in the House of Representatives (which determines the PM) were allocated from multi-member districts. A district would have a set number of representatives, and pick its reps from the top vote getters in a district. So, if it had three representatives, the top 3 vote getters would go to the Diet. This is a system that allows you to win an election without anything close to a majority, and which rewards clever strategic voting between candidates to allow multiple members of the same party or coalition to win in one district. That coordination is easier for one party instead of two–and in fact, by August of 1955, the socialist merger would go forward.

Second, Japan’s foremost postwar ally really wanted to see the merger happen. By 1955 the Occupation was over and SCAP was no more, as was the Truman Administration. But the new president, Dwight Eisenhower, was no less of an anticommunist than Truman had been. There was a lot of American pressure (and, it was later revealed, CIA funding) to both parties on the condition that the merger go forward so that the socialists would remain out of power.

Finally, there were politicians on both sides of the Liberal-Democratic divide who wanted to see the merger take place. Hatoyama, in fact, was one of them, as were his two aides Ando Masazumi and Miki Bukichi. On the side of the Liberal party, meanwhile, the party president Ogata Taketora–while he’d stayed loyal to Yoshida–also thought that maybe if he agreed to the merger he had a shot at being PM himself one day.

In fact, he did not; he was already old and fairly sickly, and would die the very next year before he got his shot. Given all this, more and more people on both sides of the conservative divide came around the idea of a merger–after all, one of the cardinal rules of politics is that holding a grudge is never as important as tallying up the next big win.

And so it was that in October, 1955, the Liberal and Democratic Parties signed a merger agreement–becoming the Liberal Democratic Party, or LDP, whose dominance of the political scene in Japan was and is so vast that the postwar political system in Japan is sometimes called the “1955 system.”

And Hatoyama Ichiro, the grand old man of Japanese politics, became the first president of this new party which would come to dominate Japan’s political scene, and its first prime minister.

Hatoyama’s role in all this is a bit unclear. Ito Mayumi, who wrote a massive biography of the entire Hatoyama family, credits him with a pretty central role in the whole process of bringing together the LDP; however other scholars, like Nick Kapur, treat him more as a symbolic totem–an old man past his prime who was held up by younger conservatives as a symbol while they negotiated an agreement. For Kapur, credit for the creation of the LDP belongs particularly to Kishi Nobusuke, who had defected from the Liberals alongside Hatoyama and became the general secretary of the new LDP. That role didn’t put him at the forefront like Hatoyama, but gave him control of the party’s internal structure–which he used to pack the party full of his own loyalists while all eyes were on Hatoyama, and then to assume power once the old man stepped down.

I have to admit that I’m more aligned with Kapur’s interpretation than Ito’s; Hatoyama was by this point the survivor of a stroke which, however “mild” it might have been, is not an easy thing to bounce back from. He was also 69 years old when the LDP was founded; not ancient, to be sure, but not a young man either, and he was already someone who did not spend a lot of time taking care of himself.

Frankly, Hatoyama reads to me as someone more concerned with taking down Yoshida Shigeru for ‘betraying’ him and stealing the liberal party out from under him than anything else.

This is a bit of a tangent, but if we step back from what we already know–that the party that results from this merger is absolutely going to dominate Japanese politics up to the present day–it’s kind of incredible that the LDP functioned at all given that it arose from this sort of old school personality conflict.

I mean, think about it: this is a party that grew out of a shotgun wedding forced by the threat of a socialist party merger (and given that everyone involved in that merger had genuine ideological views in common because they were all socialists, one could be forgiven for assuming their merger was the more stable one). The merger was only necessary because of the personal politics of Hatoyama and Yoshida, who had been fighting each other for control of the conservative movement since Hatoyama was removed from the purge lists in 1951.

The merger also forced together politicians who, despite a shared label of “conservative”, didn’t really have all that much in common with each other. There were old liberals like Hatoyama, politicians with prewar experience who viewed themselves as the defenders of personal liberty against both wartime militarism and now the threat of communism, mashed up against bureaucrats-turned-politicians like Yoshida and his followers, who were more technocratic than ideological and concerned with economic growth more than anything else. You had folks who supported Article 9 out of economic pragmatism mashed up against pro-military types who had managed to avoid being purged and who viewed Article 9 as an aberration.

It’s genuinely kind of nuts the party held together at all–and frankly, Hatoyama doesn’t really deserve credit for that. During his tenure and immediately after, the party remained divided along “political Hatoyama” followers and “bureaucrat Yoshida” followers–it’s really due to Ikeda Hayato, who took over the party in the summer of 1960, that the LDP was able to find compromise positions and move forward into being what it is now. See episode 442 for more detail on that.

Hatoyama himself was frankly not the guy for the job of bringing together conservative politics in Japan. Indeed, this is a bit of an aside, but in 1954, as all this drama was unfolding, Hatoyama was unwittingly folded into a planned attack against Yoshida Shigeru. The plot in question was masterminded by Hattori Takushiro, a former political ally of wartime PM Tojo Hideki–and involved assassinating Yoshida Shigeru so that Hatoyama could take over the Liberal Party and become Prime Minister.

Why? Because Yoshida opposed rearmament, and Hatoyama wanted to see it–and Hattori and his co-conspirators, all fellow militarists who had not been high ranking enough to be kept in jail or executed, wanted a government that would rearm Japan.

Hattori, by the way, had been able to organize his little conspiracy with the help of General Charles Willloughby, who had been the head of counterintelligence for the American occupation government and who shared a hawkish desire for Japan to rearm. The plot collapsed once the Occupation ended and Willoughby’s support (including money) dried up–but it’s indicative of how Hatoyama, despite being a wartime liberal, was perceived by members of Japan’s extreme right.

As for what Hatoyama Ichiro actually did as prime minister, I think his accomplishments are an equally mixed bag. On the one hand, he’s probably best remembered for a central act of diplomacy in postwar Japanese history–he led the drive to negotiate the Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956, which resumed diplomatic, economic, and other forms of relationships between Japan and the Soviet Union.

Those relations had been broken when the Soviets joined WWII in Asia during its final days, and the Soviet Union had refused to take part in the final treaty between Japan and the other allies signed in San Francisco in 1951 (because the Americans had excluded mainland China from the signing). Hatoyama was the guy who finally cut a peace deal with the Soviets, going so far as to head to Moscow himself in the fall of 1956 to take the lead on negotiations–while also meeting consistently with American representatives

Hatoyama wanted the treaty because it was an important step (he felt) in putting the war years behind Japan to normalize relations with the world’s other superpower beyond the US, as well as because of the simple fact of Russia’s proximity to Japan–normal relations made everything from avoiding sea collisions between fishing vessels to routing air traffic easier. Beyond this, the USSR was a permanent member of the UN security council, and had been vetoing Japan’s entreaties to join the United Nations–a roadblock to normalization that a peace deal would remove. And, of course, it never hurts as an older politician to think of questions of legacy: and what better legacy is there than a nice old treaty?

The resulting treaty did normalize relations between the two countries, though pointedly they could not come to an agreement on one issue: the status of the four southernmost of the Kurile Islands, which remain in dispute between Japan and Russia today.

The other of Hatoyama’s big accomplishments is…a bit less shiny, to be honest. This is his attempt to install the so-called Hatomander: a portmanteau of Hatoyama and gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering, if you’re not familiar with it, is the attempt to set up voting districts favorable for your own party; it too is named after a famous politician, the Massachusetts federalist Elbridge Gerry.

Hatoyama tried his own form of gerrymander even as the LDP itself was coming together in 1955. He submitted a bill on “election reform” to the Diet, one which would replace those multimember districts I was talking about with single member ones that were won by a simple majority–and which redrew the district boundaries in such a way that the demographics massively favored the LDP and hugely raised the chances the party could pick up a 2/3rds majority in the Diet in the next election.

Why 2/3rds? Because the postwar constitution specified that was what you needed in order to revise Japan’s constitution in order to, say, make Japan “normal” again by deleting article 9.

The bill was so transparent that it raised up a massive political ruckus even within the LDP (anyone from the Yoshida wing hated it), forcing Hatoyama to shelve it–and eventually to abandon election reform altogether in favor of a different political issue that had broader support: removing American-imposed changes that decentralized the education system.

And I have to say, this too reads as an odd choice. Remember, it was the very centralization of the powers of the Education Minister that got Hatoyama himself into trouble once upon a time. He’d been pushed by the military into cracking down on dissent as Education minister in the early 1930s, using his powers as a minister in a very illiberal way to do so. Clearly, however, Hatoyama didn’t see the centralized power of the ministry itself over education as the issue–just the fact that the military had been pressuring him on the matter.

Particularly given that Hatoyama’s crackdowns in the early 30s as education minister supposedly targeted ‘Marxists’, and that his justification for re-centralizing the education ministry was similarly a claim of ‘Marxist’ infiltration of teaching as a profession…well, one has to question his liberal bonafides.

Hatoyama Ichiro’s tenure as Prime Minister ended on December 23, 1956, when he retired from party leadership and handed the gig off to a longtime political ally (Ishibashi Tanzan). He’d remain in the Diet until his death in 1959 at the age of 76.

His legacy was, and is, frankly, complicated. To be honest I did not expect to spend two whole episodes on the guy but the more I dug, the more there was. On the one hand, I think it really is fair to say he was committed to his liberal politics–after all, he did take a risk during the war years when he could have simply gone along with the wartime government out of concern for his political longevity.

On the other hand, he was more than willing to use tools like the gerrymander that we think of today as pretty undemocratic to get things done–and his ferocious anticommunism and focus on Article 9 read to me, at least, a bit oddly.

Was Hatoyama a true believer in liberal democracy like his father? A calculating politician who simply saw a chance to trade on his family name and reputation? Somewhere in between? Honestly, I’m not sure–and it’s hard to draw the line. Today, you see portrayals of him that are either basically hagiographies about his sacrifices for democracy (Ito Mayumi’s writeup on him in her book on the Hatoyamas is a classic) or writeups about how he enabled some pretty not great folks to rise to the top (like Kapur’s take on him as essentially a sock puppet for the ambitions of men like Kishi Nobusuke).

Honestly, I don’t really know what to think–which maybe is the sign of a truly wide-raning political career. After all, 1915-1959 is a 44 year long political career; and in that time, not only does a single politician have to do a lot (which necessitates a lot of compromise) but the world can change around you quite a bit.

A guy who insists that Japan should be an American-aligned force in Asia with a powerful military and a capitalistic liberal order looks very different in 1933 from how he does in 1953, after all.

Next week, we’ll move on to the 3rd generation of the Hatoyama family–and the 4th, and final.