This week, we’re covering the art of rakugo–storytelling with a twist! How did rakugo emerge from the history of Buddhism, and what has enabled its enduring popularity where contemporary entertainments like kabuki have fallen by the wayside?

Sources

Shirane, Haruo, ed. Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900

Bryan, J Ingram. “Japanese Story-Telling.” Lotus Magazine 5, No 6 (March, 1914)

Adams, Robert J. “Folktale Telling and Storytellers in Japan.” Asian Folklore Studies 26, No 1 (1967)

Sweeney, Amin. “Rakugo: Professional Japanese Storytelling.” Asian Folklore Studies 38, No 1 ( 1979)

Mastrangelo, Matilde. “Japanese Storytelling: A View on the Art of Kodan, The Performances and Experiences of A Woman Storyteller.” Rivista degli studi Orientali 69, No 1/2 (1995).

Kushner, Barak. “Laughter as Materiel: The Mobilization of Comedy in Japan’s Fifteen-Year War.” The International History Review 26, No 2 (June, 2004).

Images

Transcript

One of the things I’ve always really enjoyed about history is seeing humor crossing the boundaries of time. A good fart joke from the Canterbury Tales, a silly pun in a Chinese poem, all show one of those greatest themes of the study of history: that wherever you go, you still find yourself surrounded by other people, in all their greatness and terribleness and occasional need for silly jokes.

And it’s in that spirit that I finally want to turn our attention to the topic of rakugo, first described to me as Japan’s tradition of stand up comedy. That classification, however, doesn’t really do it justice; rakugo is not just a series of comedy bits, though the basic setup–one storytellerup on a stage addressing an audience–definitely reads like standup comedy at first glance.

As an aside: The name rakugo literally means “falling words”, though more accurately it might be translate as “stories with a twist.” That name, rakugo, actually comes from the Meiji period and was not the standard term of reference for the first few centuries of rakugo’s existence–otoshibanashi, a variant reading, was more common for a good while. However for consistency and clarity, I’m going to use it here.

Rakugo is ultimately a sort of oral storytelling, but of course the tradition of storytelling is far older than rakugo itself in Japan–-and everywhere else. Fundamentally, it’s the most basic of all art forms, after all; one imagines the birth of all performance was simple storytelling. Broadly, in Japan, all storytelling traditions fall under the genre of yose–though again, that term is anachronistic, and wouldn’t have been in use in the early eras of the genre.

We’ve already talked about the old medieval of the biwa houshi–blind itinerant chanters from the 1200s and onward who would recite Buddhist texts, and then later epic historical ballads about great warriors–to entertain the masses. This is the tradition that brought us some of the great literature of the medieval era, most notably the Tale of the Heike–which began as a chanted ballad performed by biwa houshi before being systematized into a literary text.

Religion in general had a major influence on the art of recitation in Japan–the sekkyoubushi, roughly “itinerant preachers” who would perform Buddhist tales for the entertainment and edification of audiences, were another predecessor of what became rakugo. In the late medieval era (so the 1300s to 1400s), sekkyobushi would go to a down, plop down an umbrella to give them some shade, and start reciting entertaining stories that would edify the people with important Buddhist teachings–telling them fables, in other words.

Some sekkyobushi fare would be taken from the great literary works of medieval Japan. Story collections like Konjaku Monogatarishu (A Collection of Tales from Times Now Past) were popular sources. Ise Monogatari, with its combination of steamy romance and Buddhist ephemeral pondering, was another popular choice.

In other cases, storytellers would simply riff on more current events or popular histories to provide background for a story.For example, one popular sekkyobushi tale is a (mostly made up) story about a daimyo named Oguri Mitsushige, an actual historical figure who was involved in a rebellion against the Ashikaga shoguante in 1416. The rebellion is defeated, and Oguri ends up on the lamb in Mikawa province to the south of his home in Hitachi (this would be going from Ibaraki to western Aichi prefectures in modern Japan). There he stays under cover in a local inn, but is recognized by the ruffians running the place, who plan to poison him and rob his corpse. However, the serving girl they enlist to do this, Teruhime, has fallen in love with Oguri and warns him, so that he escapes. His men are all killed, but both he and Teruhime separately get away, and years later he comes back and kills all the men and rewards Teruhime.

You can see how, performed with dramatic twists and turns–he’s about to drink the poison! But wait, the loving woman intercedes! Now he dramatically rides away!–this would be a lot of fun recited as a story, and of course it has a good moral about not poisoning people to rob them, or at least being careful about who you enlist if you do.

There’s also the related genre of the koudan, essentially a type of religious lecture that evolved from the reading of Buddhist or Shinto texts. The reciter, in this case, sits behind a sort of lectern and taps out a rhythm using hyoushigi, or wooden clappers, to which he then recites a lecture or story with religious meaning.

All of these genres and styles of performance had some kind of following by the 1500s, the high age of civil war known as the Sengoku Jidai. But then, a funny thing started to happen.

First, people had more money. The wars of the Sengoku period triggered both, of course, literal arms races, but also figurative ones around stronger administration or economy–since a warlord with a wealthier domain, or one who could squeeze a bit more cash per square mile out of his lands than his neighbors, would have an advantage in a standup fight.And then, when the civil wars began to conclude in the late 1500s with the reunification of Japan, those new administrative approaches were deployed around the entirety of Japan.

Second, war is all about uncertainty, and uncertainty is never good for business. Once the civil wars ended, things got a lot less uncertain–and the economy began to grow by leaps and bounds.

All of this is, of course, an elaborate way of saying that the start of Japan’s feudal golden age–the Edo period, when the country was ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family from what was then Edo, what’s now Tokyo–coincided with incredible improvements in standards of living for people around the country.

Measuring these sorts of things is hard to do without the central recordkeeping that modern census bureaus and the like rely on. However, pretty much any indirect measurement we have, from the types of food people were eating to the houses they were living in to the clothes they could afford to the complaining high ranking samurai did about all the non-samurai who were living it up in fancy ways beyond their social station, indicate that by any measure, the Edo period was a real improvement from what came before.

And the thing is, when people have higher standards of living, they tend to have money to burn–and when they have money to burn, one of the things they tend to want to spend that money on is entertainment.

This was particularly true of the growing class of chounin, or townsmen–those who lived in large cities like Edo or Osaka, where urbanization was creating a flowering of artistic culture catering to the tastes of this newly emerging social class.

We’ve covered many of the ways this has manifested before, from a flowering print culture to the birth of new forms of theater like kabuki to bunraku puppet theater–with many of these forms also catering to the tastes of townsmen. But storytelling as a genre also began to feel the influence of people with money to burn and a desire to have some fun.

Sekkyoubushi preachers, for example, began to tip the scale towards more entertaining and less overtly moralistic repertoire, and to add accompaniments like joruri–music played on a shamisen, a type of stringed instrument.

Kodan performers began to move away from overt Buddhist themes and toward famous or exciting moments of history. Indeed, by the late 1500s, kodan performers were often called Taiheikiyomi, or “readers of the Taieheiki–a great medieval military romance. One of the most famous performers of the genre, Akamatsu Houin, called the theater he opened the Taiheikiba–the place where the Taiheiki is read.

Thus Yose, storytelling, had moved away from generally religious themes–where biwa houshi were trying to placate the spirits of the restless dead with great tales, or where sekkyobushi were trying to edify the masses with tales that would instill them with good Buddhist morality, and into something that is more recognizable as traditional entertainment. Which isn’t to say that the old stories were not entertaining–just that the genre had moved away from overtly religious justification for their entertaining nature.

And this brings us to rakugo, which evolved out of this existing web of storytelling approaches into something intended for popular audiences.

For example, more than a few storytellers began to pull from collections like the Kinou wa Kyou Monogatari, roughly “Today’s Tales of Yesterday”–which was published in 1615 and mined the existing storytelling repertoire oriented for aristocrats for more humorous fare that would work well for a popular audience. The compiler remains unknown, but the stories were wildly popular (it was arguably the first ‘best-seller’ in Japanese history).

And here’s where we get into what makes rakugo different from other forms of mass entertainment during this time period. All were intended to appeal to the sensibilities of the townsmen class–which were decidedly more over the top and less restrained than, say, the Noh theater which enjoyed an impressive pedigree and patronage from the aristocracy. But some of these new art forms–kabuki is a good example–had a self-image that was ‘classier’, for wont of a better term.

Kabuki dramatists like Chikamatsu Monzaemon were clearly interested in trying to explore deeper themes around the human condition while also putting something entertaining on stage–the art was, for lack of a better term, more self-consciously artistic.

Rakugo is not that, and Kino wa kyo monogatari is a great example of why. A LOT of the humor in that text is very sexual–particularly, unfortunately for us, the parts that translate best into English. So, in the interest of not being smacked down by the almighty podcast gods of Apple for violating the clean tag on this feed, let’s just say that early rakugo relied a lot more on various puns around male genitalia than one traditionally sees in, say, classic kabuki plays. Whether or not you think that represents an artistic improvement is, of course, for you to decide on your own.

Now, I’m not going to trace a blow by blow account of the evolution of rakugo as a distinct art form through this period, because frankly I don’t think that’d be terribly interesting unless you are very invested in the art form already (in which case you likely know it already).

Instead, suffice it to say that by the late Edo period, rakugo had emerged as a distinct artform from other storytelling traditions. Rakugo storytellers would borrow from texts like the Kino wa kyo monogatari–or less lurid options, depending on their taste–and offer performances in what were called yose halls. They would dress colorfully (part of what distinguished them from, say, kodan performers, who remained true to the Buddhist roots of their style by dressing mostly in black), and by the late 1700s had developed a repertoire of minimal gestures performed while seated on the floor seiza style that had a fixed meaning. They had also developed a host of props to be used while telling tales: a tenugui, or hand towel, and a fan are the two most common.

In the Kansai area of Kyoto and Osaka, a bookstand, hyoshigi clappers, or a giant harisen fan are also options–but that’s not a part of the Edo/Tokyo-based repertoire.

Patrons would gather in special storytelling halls, called yose, which advertised famous performers and the themes they would cover on painted lanterns out front. They would arrange themselves around a kouza, an elevated stage, on which the performer–a rakugoka–would sit. The performers would then work through their repertoire, usually performing a few stories at a time with related themes.

The single performer would do every role, distinguishing between them by subtleties of inflection, gesture, and pose. It could be incredibly challenging to do; the early 20th century performer Yanagiya Kosanji would later say in an interview that, “I have been an actor in the regular theatre, and I know that of the two forms of art, storytelling is the more difficult. The regular actor has the advantage of scenery and costume to arouse and maintain interest; the yose actor has to create interest by his own intrinsic merit and personality. And often the storyteller has to impersonate five or six characters in one story.” The performances are also intended to look naturalistic; obviously, the stories are pre-prepared, but part of the goal is to appear like you’re spontaneously telling them, which is another area of similarity to Western style stand up comedy.

Now, these stories could and can be comedic–that, and the similarities in performance style to standup comedy, is why rakugo is often translated as “Japanese stand up comedy” in English sources.

But there’s actually a much wider range to the rakugo style. Rakugo performers would also tell kaidanbanashi, or ghost stories, and many of the most famous tales are ninjo-banashi–a term that literally means “sentimental” stories, but is probably better just translated as “dramas” or “stories about the human condition.”

Still, the comic ones are far and away the most common. Their distinctive characteristic is what’s called the ochi–a term that uses the same Chinese character as the raku in rakugo.

Literally it translates to ‘fall’, but more accurately it’d be something like ‘twist’. This is, in essence, the punchline of a comic story–dramatic ninjo monogatari don’t always have one, but if they do it’d be represented by something like a 3rd act twist.

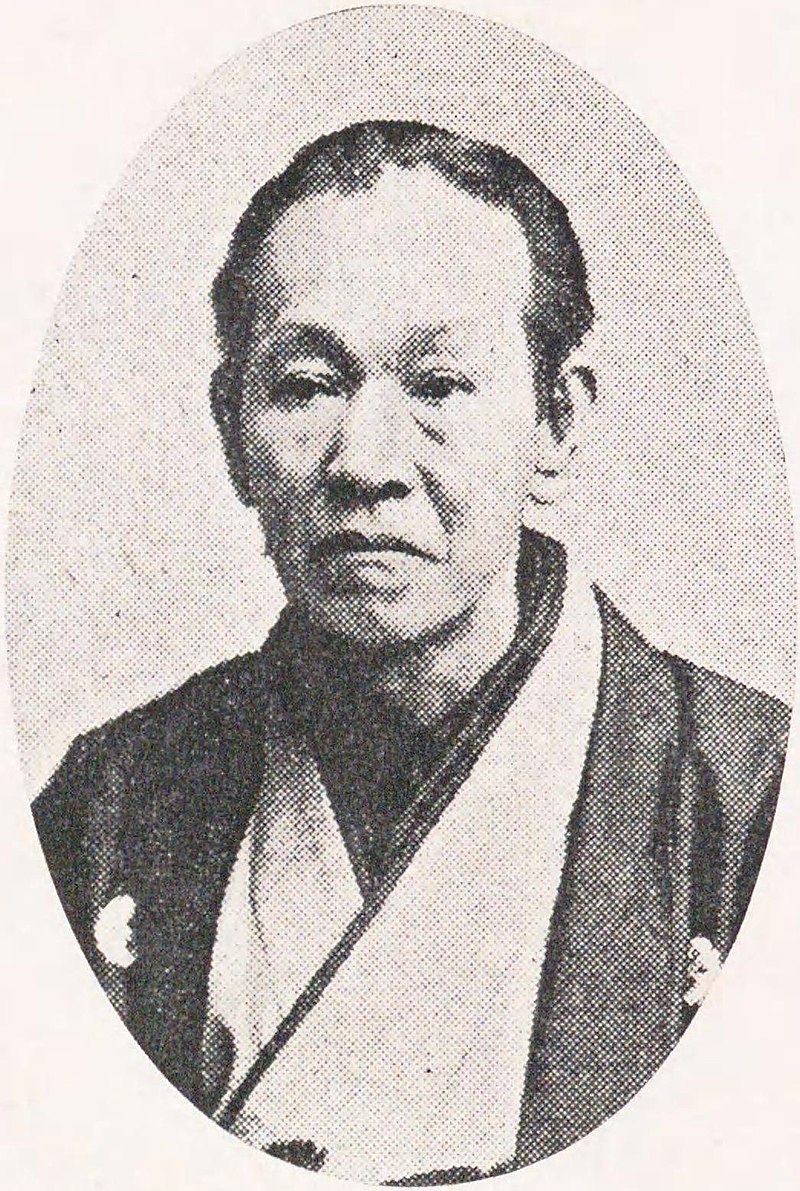

So, ok, I’m speaking very abstractly about all of this, but maybe it’ll help to add some specificity to our discussions. To do that, we’re going to turn to one of the most famous rakugo performers of all time, Sanyutei Encho–born in 1839, and a master of the kaidanbanashi, or horror story, in particular. He was famous for telling these tales in the late summer–August, right around the time of Obon, or the festival of the dead.

You know how around the time of Halloween in the US, movie theaters are full of scary movies? Same idea here.

One of his most famous works is Kaidan Botan Dourou, the Peony Lantern Ghost story, from 1861. The tale is adapted, like a lot of classic rakugo, from an older story–Botan doro, or the Peony Lantern, part of a collection published almost 200 years earlier, and which is in turn borrowing from (or less charitably, ripping off) a story from the Chinese ghost stories known as Jiandeng xinhua, or New Tales Under the Lamplight. Sanyutei himself then appended other famous ghost stories onto the narrative.

The plot is a bit tangled, but bear with me. It’s set in Edo in 1743, and stars a samurai and hatamoto, or direct vassal of the shogun. His name is Iijima Heitaro, and the action starts with him quarreling with another samurai who is drunk and behaving rudely. Heitaro kills him and then, purely by chance, ends up hiring the man’s son, named Kousuke, as a servant. Here, the narrative branches into two distinct storylines that only come back together at the end.

In the first, Heitaro’s wife dies in childbirth around this time, giving birth to their daughter Otsuyu. Heitaro decides to take her maid, Okuni, as his new mistress–but Okuni is having a secret affair with Heitaro’s neighbor, named Genjiro, and the two decide to kill Heitaro to preserve their love. Kosuke the servant gets wind of this and tries to kill Genjiro to stop the plot, but does so at night and so accidentally stabs Heitaro instead–Heitaro, knowing he’s responsible for the boy’s father’s death and assuming this is an act of vengeance instead of loyalty, decides not to defend himself from the attack. Kosuke then swears revenge on Okuni and Genjiro, who flee and go into hiding.

In the second story, Heitaro’s now orphaned daughter Otsuyu falls in love with a ronin named Shinzaburo–but her father’s disapproval and general social propriety prevents the daughter of an upright hatamoto from being with a ronin. She was apparently really into it, though, because she literally dies of longing for him–and her ghost returns every obon to haunt him. Shinzaburo is apparently not into ghosts, because he hires a Buddhist exorcist to protect his home with sutras that will ward her off. But Otsuyu is not deterred, and bribes Shinzaburo’s servants, Tomozo and his wife Omine, to remove the wards–she then possesses and kills the object of her love. Tomozo and Omine also run off–and find Okuni and Genjiro! Okuni begins having an affair with Tomozo, who kills his wife when she finds out, and then Kosuke shows up and brings everyone to justice and avenges his former master who killed his father.

Like I said: it’s quite the plot. And I can see how it’d be satisfying as a slow burn tale told over several hours instead of summarized in a few minutes.

Not all tales were this dramatic, of course. Here’s some examples I found in translation in a journal article from the early 20th century: “’ Once upon a time a certain dyer called in a blind masseur; and before permitting him to begin operations inquired his fee. The man replied ‘Two hundred mon for all, above and below.’ The dyer expressed sat faction and told the masseur to go ahead. When the dyer had enough, he called in his wife, and had her massaged also. Then he summoned his servants, both male and female, and had them all massaged. The poor blind masseuse was delighted at his luck but when the money was handed to him, lo, there was only 200 mon.. Upon remonstrating that he should receive 200 mon for each person massaged, the dyer asked: ‘Did you not say 200 mon for all, above and below?’ (In the vernacular, “above and below” may also mean, master and servants). The masseur had to admit that he had said as much, and so went off with his small fee, without a murmur. He was determined to get even, however. He got hold of a friend of his and arranged with him to take a piece of cloth to the dyer asking him to say to the latter: ‘I want this cloth dyed in first-class style, without regard to price.’ The dyer, glad have so good an order, set to work and produced his best color. The blind masseuse came with the man to receive it; and taking up the parcel, walked off without offering any payment. When called back, with the demand as to what he meant by going off without paying for it, the masseur only replied ‘Did I not tell you when I ordered it that it was to be done without regard to cost?’ (regardless of cost also meaning in the vernacular, without payment). Did you not agree to dye it without regard to price?”

Here’s another: “It is said that in this world there are eight kinds of fools, and the following are some examples. A farmer hearing a noise on the roof of his house one night, went out to discover the cause of it. There he saw his two sons perched on the house, one with a long bamboo pole, which he held aloft, pointing skyward with a sweeping motion. The old man could not make out what they were up to; then he heard the younger son remark to his brother: ‘You can never knock down those little yellow things with that short pole; you must get a longer one; tie two bamboo poles together!’ ‘What are you two youngsters trying to do?’ inquired the father at last. ‘Why we are trying to knock down the stars,’ explained the older son. ‘Go on, you stupid fellows,” shouted the old man, ‘you will never knock those down, even if you had longest pole on earth. Don’t you know those are the holes through which rain falls?”

Finally, there’s this one, which I have to say I particularly like: “A samurai was once walking along the street when he saw a sign to the following effect: Fencing and sword practice of all schools taught here! On going in to inquire, he was told that none of the household knew anything of fencing. Thereupon the officer demanded why they put out the sign. “Oh,” replied one of them, ‘that is only to frighten away robbers.’ I’m gonna have to try that myself!

By the late Edo period, rakugo had developed into a dramatic art that shared a lot of commonalities with many of the other performing arts of the era. It had solidified into lineages that passed down specific stories or styles–and even stage names.

For example, there’s a whole Sanyutei school who use names derived from Sanyutei Encho’s that is still operating down to this day. Sanyutei Enraku VI died just last year, actually, after a long career as a rakugoka with a penchant for social satire. He was born in 1950; apparently his dad was a cop, and he joined the leftist student movement in the late 60s to rebel against him before settling on rakugo as a career. Interesting guy!

Similarly, that Yanagiya Kosanji I quoted earlier is actually Yanagiya Kosanji VII; Yanagiya Kosanji X passed away in 2021, by which time he had literally been designated a national treasure by the government.

Rakugo was also extremely popular–by one estimation there were more than 120 yose halls for performances in Edo by the end of the feudal period in the 1860s, varying in capacity from a few dozen to hundreds of people.

However, unlike many of Japan’s other traditional arts, rakugo did not really experience a falling off with the end of feudalism. In large part, this was because of the form’s adaptability. Where other Edo period performing arts like kabuki had developed fixed repertoires that tended to dominate the form, rakugo did not. Instead, a division emerged between “shinsaku”, or “newly made” rakugo, pretty much anything from the late 19th century onward, and “kodan”, or classic rakugo, which is anything that predates that.

Kodan rakugo operates somewhat like the classic repertoire of kabuki–the famous stories are well known and retold over and over. But the shinsaku kept rakugo current–new stories were created to reflect the new realities of post-feudal, modern Japanese life. And as a result, rakugo actually grew in popularity–by the early 20th century, there were 150 performance halls in Tokyo.

The form did face some competition from manzai, a type of duo comedy that also dates back to the Edo period where one person plays the boke, or funny man, and the other the tsukkomi, or straight man–which is apparently one of those comedy ideas that literally transcends time and space.

It also faced some competition from a new medium–film, which first arrived in Japan with Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope in the fall of 1896. However, here too rakugo proved remarkably adaptable–if you know your Japanese cinema history, you’ve probably heard of the benshi, or silent film narrator. This is exactly what it sounds like; a performer would be in the theater narrating the action of a silent film and explaining what’s happening as it goes. The benshi tradition is, to my knowledge, unique in the history of cinema–and both the style used by benshi (particularly in comedic films) and many of the performers themselves were drawn from the world of rakugo.

Rakugo was popular enough, in point of fact, that in the early 20th century it drew the attention of the state in ways both positive and negative.

Obviously, comedy–really all art–can and very easily does get political. That same early 20th century article I found describing rakugo routines? The author also made a note that in every performance hall he was in, there was at least one uniformed policeman making sure nothing that was said crossed any lines around politics or public indecency.

Even so, you could get away with a bit of poking fun at the state; for example, the performer Yanagiya Kingoro got his start in the 1920s doing bits riffing off his experiences serving as a conscript in the Imperial Japanese Army in Korea.

One of his most famous bits involved an encounter between a conscript named Yamashita Kettaro (based loosely on himself) who sings a ditty mocking the military (the lyrics are “non-com officers are a pain in the butt/corporals are an annoying buncha mutts/ranking officers are short on dough/cute new recruits are just here for show”). An officer hears him singing and proceeds to scream mercilessly at him, with the enlistee Yamashita basically trying not to freak out in response. Definitely an opportunity for some excellent performative voice work–and, in a time when conscription was still the law in Japan, a story that would resonate with more than a few adult men.

It also apparently resonated with some in the army, but not always in the best way; Yanagiya would later say that every so often, particularly by the mid-1930s, he’d get letters from the Kempeitai, the military police, telling him not to perform certain routines despite them not, from what he could see, breaking any laws around public decency or morality. When he asked for clarification as to why a specific routine was not to be done, he never got it–but he followed the ask anyway

By the 1930s, the Japanese government was actively trying to mobilize rakugo to support its policies; a 1934 pamphlet on public morals published by the police bureau noted that because of, ‘the manner in which today’s society is organized, the lifestyle of the masses is exceedingly monotonous, uninteresting, and dull…as such, entertainment is not merely a diversion or a way to kill time. It is, in fact, an indispensable element of living.”

This pamphlet was not, in fact, intended to instill existential dread about the meaninglessness of modern life (that was just a fun side benefit)–the point was that since entertainment was now an essential of modern living, it must be made to encourage ‘good habits’ (which is to say, pro-government ones) instead of bad.

Certainly the imperial Japanese navy agreed, since starting in 1935 it hired Yanagiya Kingoro–by this point, because of his routines, very much tied to the image of the imperial military–to produce a series of pro-navy works. The book he produced, Kaigun Banbanzai–one million cheers for the navy–was then turned into a film called Ore wa suihei, or I’m a sailor.

Funnily enough, thanks to a medical issue that had led to his army discharge, Yanagiya was bald–which the navy leadership thought would harm its image by making the service look weak and old. The film’s director was thus told that under no circumstances could he show the top of his star’s head on screen–he compromised by forcing Yanagiya to wear a hat in every scene, including ones where he was supposed to be asleep.

By the time of the start of the China War, the idea that rakugo–and other arts–could be mobilized in the service of the military leadership and its goals had a great deal of currency in the upper levels of government. For example, a Home Ministry report from November, 1937 noted that, “rakugo…and other diversions, amusements for the masses are debasing themselves to the lowest common denominator. The actual quality of entertainment is plummeting towards the crude, and social morals are not being heeded. Moreover, while it is true that many of the diversions treat the China Incident, the content is usually unpolished.” Which is to say, of course, that it was not toeing the state line on the issue.

To ensure that rakugo performers–and everyone else–would, the Home Ministry introduced a registration and licensing system for rakugo, manzai, and singers in December, 1938. That system was then used as the basis for imposing state censorship of all comedy routines in January, 1939–and a ban on performers making “a display of their eccentricity” by choosing strange or foreign-sounding stage names in April, 1940.

The Imperial Army also began setting up warawashitai–roughly, “make you laugh brigades” in 1938, bringing together approved rakugo performers (and singers, and manzai duos, and others) to perform in China to entertain the troops. In essence, these were the equivalent of wartime USO performances in the US military, and they became big business. Particularly as the war-era privations began to ramp up and fewer civilians had money to spend on entertainment, government-sponsored gigs became one of the main ways to make a buck. Pretty much anyone who could take one did.

And these continued right up to the end of the war; in May, 1945, two of the most famous rakugo performers of their time, Kokontei Shinsho and Sanyutei Ensho (not Encho, but from the same lineage) were sent to Manchuria for a tour to entertain troops there. Kokontei Shinsho would later joke in his autobiography that he took the job because the firebombing of Tokyo had destroyed all the distilleries, and he hoped to be able to find good booze still available on the mainland. Both men would end up still in Manchuria when the Soviets invaded, and would stay in prisoner of war camps until 1947 before finally being repatriated. None of the performers involved in supporting the war effort were purged after it–most, like Shinsho and Ensho, were able to return to their normal civilian lives.

Today, rakugo is note quite what it was; there are only a few yose performance halls left (five in Tokyo, and two in Osaka). However, rakugo has also adapted to the times–it’s a format that lends itself well to both television and to recording, and so is even more accessible than it used to be despite how few venues there are.

Indeed, rakugo is in a certain sense higher status than it has ever been. The rakugoka Katsura Konan II recalled later in life that, when he began his career in the early 1940s, his parents had threatened to disown him for going into entertainment as opposed to a “real job”; now, he was inundated with requests to give talks around the country, and even to come to universities and speak before their rakugo kenkyukai, or study societies.

And that’s, to my mind, the most interesting thing about rakugo. We’ve talked about a lot of traditional arts on this podcast, and one thing most of them have in common is that these days, they exist in a weird sort of cultural limbo. On the one hand, arts like kabuki or noh or what have you are put up on a pedestal, treated as indicative of traditional Japanese culture and a part of the shared cultural heritage of Japaneseness. On the other hand, because of that very status they’re nowhere near the heights of popularity they once enjoyed; these cultural treasures also have to be kept on life support by subsidies and grants and modified performances that are digestible for tourists.

This is, to be fair, not a fate unique to Japanese traditional arts–one could say the same of Shakespeare, for example, who certainly has his fans but is not what I would call organically popular.

Rakugo, however, has not followed the fate of these other performance styles, and I think a lot of that comes down to its adaptability. The core of rakugo is simply the desire to hear a good story told well–the stories themselves can be traditional, but they can also be new ones. And it’s that flexibility that has allowed rakugo to survive and thrive in so many different contexts throughout the years.

Has rakugo gone international, with stories in other languages and performances by people of other nationalities or is the performances only in Japanese by Japanese artists?

There’s an anime about rakugo that I love called Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjuu about how a young man grows up to be a rakugoka.

Can you at least give us a link to see the rakugo dick jokes?