If the first translation of a text on smallpox vaccination in Japan was finished in 1820, how did it take another 29 years for the first mass vaccination campaigns to begin? The answers involve everything from a German doctor accused of being a spy to networks of physicians trying to navigate obscure bureaucracy. And they might remind you more of the last few years than you’d think.

Sources

Janneta, Ann. The Vaccinators: Smallpox, Medical Knowledge, and the ‘Opening’ of Japan.

Fairfax, Irwin. “Smallpox in Japan.” Public Heath Reports 25, No 35 (Sept, 1910).

Bowers, John Z. “The Odyssey of Smallpox Vaccination.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55, No 1 (Spring, 1981).

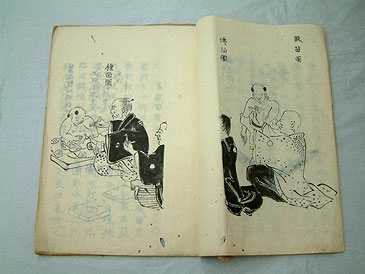

Images

Transcription

Last week, we covered the long and circuitous route by which knowledge of smallpox vaccination made it to Japan. It took 22 years from the invention of the vaccine by the English physician Edward Jenner in 1798, but in 1820 the Nagasaki-based translator Baba Sajuro completed a text on vaccination and how it worked.

So, job done, right? Now all the information needed to create vaccines and crush one of the great scourges of human health is readily available. Surely from this point onward nothing can go wrong!

Except, not quite. For one thing, as pretty much anyone who has lived through the past few years knows by now, it’s one thing to have the technology required to create a vaccine. It’s quite another to manage a massive rollout such that anyone at risk from a disease can be effectively immunized. After all, you need to train a bunch of people in how to administer vaccines, and set up the logistics to transport your vaccinations everywhere–quite a bit easier in an age of mass refrigeration, by the way, as trying to keep the mild cowpox contagion alive long enough to transmit it proved a bit of a trick.

You also need massive public health campaigns to teach people the benefits of vaccination and overcome any hesitancy they might have around it. After all, on its face the idea does seem kind of nuts–deliberately shoving some very gross diseased matter into your body so you’ll get kind of sick, but not badly sick, but don’t worry because then you’ll be immune? I mean, even for someone thoroughly convinced of the benefits it sounds kind of insane.

All of these issues apply to basically any vaccine rollout, from smallpox to polio to COVID-19. But, because a regular public health campaign wasn’t tricky enough, there were some unique problems for anyone interested in distributing smallpox vaccines in Japan just to make life extra spicy.

For one thing, while Baba Sajuro completed a translation of a text on smallpox vaccination prior to his death, he’d done so without authorization as a part of the bureaucracy of the Tokugawa shogunate that was viewed–because of its contact with ‘dangerous’ foreign ideas–with a bit of natural suspicion. As a result, Baba never tried to publish his work, which is, you know, pretty necessary for people to actually read it.

That secrecy created other problems as well. We talked briefly last week about Nakagawa Goroji, who, when he was returned to Japan as a goodwill gesture, carried with him a booklet on smallpox vaccination–the same one Baba ended up translating. We’ve also encountered Nakagawa before; after this point, he’ll become a smallpox vaccine booster, and among other things will be hired by the shogunate to help vaccinate the Ainu of Hokkaido (less as a goodwill gesture and more as a way to keep their numbers up and ward off Russian colonization.)

Thing is, Nakagawa refused to actually teach anyone else how to give vaccinations–treating it instead as a sort of secret knowledge only he could possess. Such an approach was not uncommon at a time when schools of everything from martial arts to flower arranging prized their ‘okuden’–’inner transmissions’–as special knowledge to be passed down only to those who had truly earned it. But one guy can’t vaccinate an entire country–and it’s also somewhat unclear based on the records available if Nakagawa even had access to cowpox lymph or if he was simply faking it.

Beyond these issues, the Tokugawa shogunate didn’t really have a public health infrastructure that could actually help promote vaccination. There was no samurai surgeon general of the shogunate–and even if there had been, the centralized feudalism of early 1800s Japan didn’t really allow for a government-sponsored rollout.

The central government of the Tokugawa shogunate had responsibility for things like defense issues and foreign affairs, but by longstanding tradition left the 270-odd feudal domains to manage their internal affairs so long as none of the nationwide laws (like the ban on Christianity) were violated. Public health was squarely in the ‘internal affairs’ camp for the domains–there wasn’t really any sort of tradition of the central government stepping in to help manage it.

And most domains didn’t really have a tradition of active intervention in public health–of proactive measures like providing doctors and hospitals. To the extent domains did have health measures in place they were often reactive: quarantines of badly infected areas, or prayers in the name of the lord at shrines and temples.

Now, none of this should be taken as suggesting it would be impossible for either the shogunate or individual domains to run vaccination campaigns, but it did mean there wasn’t really an existing playbook for how to implement them–and when you’re trying to get vaccines out to people, logistics can count for just as much, if not more, than pure scientific knowledge.

So what did happen to the smallpox vaccine in Japan after 1820? To answer that question, we must return once again to Nagasaki. In 1817, with the Napoleonic Wars now concluded, a newly independent Dutch government was able to resume its annual missions to the Dutch outpost at Nagasaki. Hendrik Doeff, the head of the mission–and the guy whose remarks about vaccination had gotten Baba Saburo interested in the topic–was finally rotated off and replaced with a new leader, Jan Blomhoff.

Blomhoff was apparently a big believer in smallpox vaccination, which by this point had nearly 20 years of history back in Europe backing its effectiveness. And his correspondence makes it very clear that Blomhoff was a big believer in the vaccine–and really wanted to see it find footing in Japan. Why he felt so strongly is not entirely clear–it may have been on his mind because his son, when he left for Japan, was only two–and thus squarely in the danger range for the disease himself.

By 1820, Blomhoff was writing back to the Dutch controlled island of Java in what’s now Indonesia requesting cowpox lymph be shipped to Japan for a program of vaccination. By 1823, Dutch government records indicate that shipments of lymph for vaccination had become standard for all Dutch ships coming into Nagasaki. Clearly, the powers that be in Java agreed with Blomhoff’s drive to promote vaccination.

Unfortunately, Blomhoff’s early attempts were…well, not terribly effective. Three things hindered his initial attempts to spread vaccination. First, explaining to Japanese who volunteered for the procedure exactly what was going on proved a bit of a challenge. Remember, vaccination involved a small amount of cowpox lymph being placed under the skin via incision–it absolutely had to be left there for the brief infection and immunity to function. However, inquisitive patients and their families would often remove bandages and pick at the vaccination sites–and if they didn’t, curious Japanese doctors often would. This was the rationale given by Blomhoff in a report home as to why the initial round of vaccines from 1820–done by the Dutch mission doctor, Nikolaas Tullingh–failed to take.

Second, it must be remembered that foreigners were not exactly viewed with friendly eyes by average Japanese people–even in Nagasaki, where they were at least an occasional sight. Requests by the Dutch that local children be sent to their mission on the isolated artificial island at Deshima in Nagasaki harbor proved a hard sell, to put it mildly–and that was assuming the Japanese officials who were constantly rotated through the Dutch mission (to ensure none of them became too friendly with the Dutch and broke the rules for them), were willing to allow kids onto the island at all. As a result, many of the patients of Blomhoff’s vaccination drive were older, in their mid to late teens, and thus had likely been exposed to smallpox already–having survived, they were now immune.

Third, and this would prove an issue for decades to come–the lymph used in vaccinations has to be prepared before insertion, and set up in storage to be shipped around. You can’t just run off and grab the nearest sick cow. So prepared lymph had to be shipped in from the Dutch outpost in Java, and even with careful packing procedures it was not easy to ensure the lymph survived the journey. Biological material is often pretty volatile, after all, and would ‘spoil’ in transit and become useless.

Still, Blomhoff’s enthusiasm for vaccination gave him admirers, as did his concern, which appears to have been totally genuine, for the health and wellbeing of Japanese children. In particular, two Japanese doctors, Minato Choan and Mima Junzo, were by early 1823 working with Blomhoff as medical assistants–and helping to explain to patients what exactly was being done to them and why, even if they really wanted to, they shouldn’t go peaking under their bandages.

Both Minato and Mima were rangakusha–students of “Dutch Learning”, as it was called, since the only way to get their hands on Western texts was by buying them from the Dutch. Both had studied in Edo and come to specialize in vaccination, and when they heard strange tellings that the Dutch in Nagasaki were now saying they could prevent the deadly smallpox by cutting your arm a bit and shoving some gross stuff from cows in it…well, I mean, that’s the kind of thing you just have to see to believe, right?

Minato and Mima both had a chance to begin picking up the basics of vaccination with a round of lymph provided by the Dutch in May, 1823. However, they wouldn’t have long to work with Blomhoff or his physician Nikolas Tullingh, as their three year rotation in Japan came to an end in the fall of that year.

Still, their timing was good in two respects. First, both Blomhoff and Tullingh had, despite the mixed success of their vaccination efforts, managed to make friends among the Nagasaki leadership. The shogunal officials in the city-which, because of its strategic value in the foreign trade, was managed directly by the shogunate-had come to trust their good intentions, and more broadly the intentions of the Dutch in teaching Western medicine and vaccination specifically.

Second, Blomhoff and Tillingh’s replacements proved extremely fortuitous. The new chief factor, Johan Willhelm de Surtler, was not particularly notable and served a basic three year term in Japan. His physician was another matter: Philip Franz von Siebold is, in fact, so famous that we’ve already done a whole episode on him.

I will not retread that ground here; you can check out episode 248 if you’re curious about Siebold’s career specifically. For a quick refresh on what matters to us about Siebold: he was a German-born and university trained doctor who volunteered to join the Dutch military for the chance to travel abroad. Given the chance to go to Japan–a place most people from Europe would never be allowed to see–he jumped at the opportunity.

Siebold was a born scientist, interested in cataloging everything from flora and fauna to ritual and religion. This is, in fact, what he’s best known for; his accounts of what he saw in Japan, as well as his translations of Japanese texts, make him a fascinating window into the tale end of feudalism in Japan.

For us, however, what matters most was Siebold’s medical practice. Upon arriving in Japan, he was quickly contacted by Narabayashi Souken, a Nagasaki-based scholar of rangaku, or Dutch, that is to say Western studies. Narabayashi was from one of the hereditary families of interpreters maintained by the shogunate to handle the Dutch language and facilitate trade–the Narabayashi family specifically also had an established tradition of working on the side as scholars of Dutch knowledge, particularly medicine. So Narabayashi Souken was naturally thrilled to have a chance to speak with someone who had trained in medicine at an elite European university.

Initially, Narabayashi and a few other Dutch speaking facilitators came with students to Deshima, the artificial island in Nagasaki harbor, to take lessons in Western medicine provided by Siebold: focused, in the preferred teaching style of the time, on a combination of lectures on everything from anatomy to medical botany combined with lab practice of Siebold demonstrating techniques.

Eventually, however, Narabayashi was able to use his influence to get Siebold permission–rather unusual by the 1800s, though it had been more common in earlier eras–to leave the Deshima island and venture into Nagasaki proper. By mid-1824, Siebold and Narabayashi received permission from the machi bugyo, or city magistrate, to construct a combination clinic and school on the outskirts of Nagasaki. That clinic, called the Narutaki school, is now the site of a museum dedicated to Siebold’s time in Japan.

The Narutaki school would eventually take about 50 students a year, either associated with the Narabayashi family or the broader world of medicine-focused rangaku–called Ranpo, or Dutch medicine, to distinguish it from kanpo, traditional Chinese medicine. Siebold took several doctors with prior knowledge of Western medicine into his faculty; for example, Mima Juzo, one of the doctors who had helped the previous Dutch resident physician Nicolaas Tullingh administer vaccines, was one of his teaching assistants.

Siebold, by the way, did not collect tuition from his students; he was paid, instead, in information in the form of everything from biological samples to notes on JApanese medical, religious, social and other practices. Students would produce ‘dissertations’ on their samples in the style of an essay, and be awarded a diploma with a red wax seal on it like a European university upon completing it–entitling them in turn to learn at the Narutaki school and then demonstrate their affiliation with the school. This material in turn formed the basis of Siebold’s writings on Japan (most famously his work Nippon) that made him famous around Europe when he returned home.

Siebold’s influence wasn’t just confined to Nagasaki. In 1826, he was a part of the Dutch mission dispatched to Edo for sankin kotai–the Dutch mission, like Japan’s feudal lords, were expected to go to the shogun on a regular basis and attend to him in person. Part of that process, for the Dutch, involved meetings with the shogun and members of his court to provide demonstrations and information about the West. Siebold, of course, was brought along to show off his medical knowledge.

All along the way, one of the things he was teaching was the art of vaccination. By this point, the yearly Dutch trade ship coming to Nagasaki was always carrying cowpox lymph, and so the Narutaki school became in a sense Japan’s first vaccination clinic.

And on the 1826 trip to Edo, Siebold performed several vaccinations in front of doctors for the shogun and his family–albeit only for demonstration purposes, given that Siebold himself noted that the lymph he was using was old and likely no longer active and capable of triggering an immune response.

Despite promising moments like this, however, Siebold’s career in Japan would not end on a particularly high note. Despite his seeming hopes that the shogun would allow him to remain in Edo and begin a campaign of mass vaccination, no such permission was forthcoming (which is just as well, as Siebold had no clear plan to get the amount of cowpox lymph he’d need for that).

Eventually, he’d be forced to leave Japan in 1829 after he was found to have taken back from Edo several prohibited items–most notably maps of northern Japan, leading to fears he was a Russian spy helping the czar to subvert the area’s defenses. The so-called “Siebold Incident” didn’t just force the doctor out of the country–many of his close associates, including rangaku scholars back in Edo who were found to have illegally provided him with materials–were imprisoned or executed.

The details of the so-called Siebold Incident are beyond what we have time for here–again, I’d urge you to go look at the previous episode on him if you want to know more about it or his career in general. What matters for us about Siebold is that while he was in Japan, he had a pretty high profile among rangakusha, and especially ranpo, medical practitioners who focused on Dutch/Western techniques. Siebold was a sort of sensation among the medical community (particularly ranpo doctors) whose appearance served to boost interest in Western medicine.

Siebold also served to ‘level out’ connections between ranpo doctors, in a sense. This is a bit tricky to think about, but bear with me: up until this point, ranpo medicine was divided, like pretty much every other skillset in Japanese history, into various competing ryuha, or schools.

These ryuha would be associated with a foundational figure whose knowledge was then passed down among students, with only the best students receiving access to the most advanced information. The relationship was practically familial–indeed, leadership of a ryuha was often passed down within a single family, and if no suitable heir was available in the next generation one would be adopted from the ranks of leading students.

This approach to organizing knowledge was used in everything from the martial arts to calligraphy, including medicine. And it is remarkably effective at passing knowledge down–but the competing schools approach does not, unfortunately, do a great job of facilitating cooperation between people of different schools.

Siebold, however, helped break down the walls between schools of ranpo–doctors from different ryuha who studied with him were suddenly linked by a shared teacher in a way that encouraged the construction not of a vertical relationship, a master and student with one person in the superior role, but a horizontal one–shared learning from one instructor. The value of that in terms of building connections between practitioners of ranpo, getting them to share knowledge, is hard to understate.

It helped that many of the ranpo doctors out there were already deeply devoted to their craft, and not of particularly high status themselves. Most ranpo doctors were either from the upper ranks of the peasantry–in which case they were looking for new careers to enhance their social prestige, and maybe even get them out of the countryside and into the big cities–or the second or third sons of samurai families who were locked out from inheriting the family job (which at any rate would not be enough to sustain the family given the meager nature of samurai stipends). For both of these groups, a career in medicine provided an alternative path to earn a living and climbing a social hierarchy that was nominally frozen in place.

Ranpo medicine specifically was a career that required serious passion and skill–the requirement to be able to read Dutch texts alone meant that most doctors were in their 30s or 40s by the time they started actually learning medical techniques.

In her seminal study of smallpox vaccination in Japan, Dr. Anne Jannetta focuses on the biographies of seven men who became ranpo doctors and were particularly involved in spreading vaccination as a practice. She found several interesting commonalities; of the seven, all but one were either farmers or the second or third sons of low-ranking samurai families (the seventh was the son of a practitioner of kanpo, or traditional Chinese medicine). All thus came from backgrounds where social mobility was a major concern.

For example, probably the most famous of these doctors is Ogata Koan, the third son of a samurai family born in 1810. Ogata would at the age of 15 ask his parents to adopt him into another family–he claimed in the letter requesting this it was because his physical frailty made him ill-suited for the life of a warrior, but likely he’d been coached to say that by his parents, who knew that a third son did not have great prospects in a warrior class where there were not enough official positions to go around.

By 1826 Ogata was enrolled in a school of traditional Chinese medicine in Osaka, and there discovered an interest in Western medical techniques, eventually moving to Edo to study with scholars there. By 1836 he was running his own school of “Dutch medicine” in Osaka.

Another example is Sato Taizen, born in 1804 to Sato Tosuke, a peasant from northern Japan. Tosuke, like many peasants in the 1800s, left the countryside and came to Edo looking for employment. He would eventually find it in the Ina family, a household of samurai hatamoto, or direct retainers of the shogun. And Tosuke would arrange for his young son to study with the Ina family heir, giving him access to an education that would in turn open up several new potential careers–including medicine. His education would allow him to get his foot in the door of one of Edo’s academies devoted to ranpo, and from there he would go on to become a well known scholar of the subject.

Both Ogata and Sato would go on to study with former students of Siebold–both would also spend time in Nagasaki, though post-Siebold it was no longer possible to meet directly with the Dutch and the acquisition of Dutch-language books was much harder than it had been. Still, Nagasaki had more schools and scholars devoted to the study of things Western than anywhere else–and more speakers of Dutch as a language–and was thus still a desirable place to study.

For Jannetta, biographies like these demonstrate a few things. First, these doctors were coming from the same social groups that eventually helped drive the overthrow of Japanese feudalism–upper peasants and lower samurai. These were people with enough status and wealth to be educated and thus politically active, but who ran up against firm barriers to their advancement politically and socially created by the shogunate and the feudal social system. Medicine was, for many of these doctors, a way to circumvent these barriers and climb socially–and their backgrounds meant these men were less concerned than those of high status about a career in something non-traditional, like ranpo medicine.

Second, these men traveled a lot. They moved between schools and cities like Edo, Osaka, and Nagasaki–scholarship was, after all, a totally reasonable reason to request a travel permit and circumvent the rules intended to keep the population from moving around too much. Thus, these doctors were plugged into medical networks of professionals around the country–like the kind you’d need to call on for a campaign of mass vaccination.

Third, they were talking across schools. These men often shared translations of Dutch medical texts–the most recent ones they could get, where in the past not as much attention had been paid to the recency of material. Sato produced a translation of a work on bone-setting in 1830, and Ogata translated a text on vaccination in 1836. Ogata also worked on Japan’s first medical journal, Taisei Mei’i ikou (the Journal of Articles by Western Physicians) in imitation of medical journals brought to Japan by Siebold. The journal only ran for a few years, but included work by Ogata as well as several other students from different lineages (a few of whom had worked directly with Siebold).

All of this is an elaborate way of saying that, to borrow Jannetta’s words, these scholars had begun to construct a professional network, the same kind of network that ties, say, me to other teachers when we talk about our ideas at conferences or online. And those networks are crucial to quickly distributing ideas and practices–like vaccination.

Indeed by the mid-1830s this network of doctors was already beginning to spread the related practice of variolation–the use of infected matter from smallpox which does produce immunity, but is far more dangerous than the cowpox vaccine (though still less dangerous than catching live, full-strength smallpox). Sato Taizen variolated his own son in 1836, for example.

This technique never fully caught on, though–even though the danger was reduced, it was not zero, and so generally people were only willing to use variolation during larger smallpox outbreaks when the risk of contracting the live disease was much higher.

Probably the most important thing this network of doctors accomplished was finding the ears of sympathetic daimyo, or regional feudal lords, who could be convinced of the value of Dutch medicine and especially of vaccination. Such men were useful both for the obvious reason–their patronage was a source of extremely useful financial support–and because of their government connections.

After the Siebold incident, it had become nearly impossible for ranpo physicians to talk directly with the Dutch on Deshima given the shogunate’s growing fears of Western spies. This meant that even as, in the 1830s, a consensus was beginning to build about the effectiveness of Jennerian-style vaccination, it was not possible for interested doctors to, say, request a shipment of cowpox lymph or scabs from the Dutch to start vaccinations with.

Daimyo, however, could place orders directly with the Dutch, and so during the 1830s many ranpo physicians from this network poured their time and attention into convincing major daimyo of the utility of vaccination–for example, by providing them with translations of the latest Western medical techniques endorsing the practice as both effective and avoiding the dangers of variolation.

And this paid massive dividends. By the 1840s, some of Japan’s most powerful daimyo had come around to the practice. For example, Nabeshima Naomasa, the lord of Saga province right next to Nagasaki and one of very few kunimochi daimyo–a lord who ruled one of Japan’s 60 provinces outright–eventually endorsed the practice.

He wasn’t even the biggest get–by the mid-1840s two members of the roju, the council of senior advisors to the shogun, were vaccination supporters. Indeed, we’ve encountered their names before: Abe Masahiro and Hotta Masayoshi, who together would lead the shogunate through the 1850s and the early years of the foreign crisis after the arrival of the Americans in Edo in 1853.

As early as 1843, these daimyo were writing to the Dutch with requests for assistance in a vaccination program, but the actual importation of materials for the vaccine was held up until 1849–largely because of uncertainties between the daimyo and the shogunate itself as to whether the shogun needed to give his permission for this new technology to be imported. After all, one of the ways the shogun maintained his control over Japan’s political system was by carefully controlling the importation of Western technology–thus ensuring no one daimyo was able to, say, buy a bunch of modernized weapons and overthrow the shogunate.

Years of political maneuvering at Edo finally culminated in a request to the Dutch on the behalf of the shogun in 1848, and the next year’s Dutch trade ship, the Stad Dordrecht, delivered a shipment of stable lymph to Otto Mohnike, the German born physician stationed in Deshima.

From here, progress was frankly incredible. Mohnike himself does deserve a lot of credit for that; he’d thought ahead carefully and come up with a clever plan to distribute the vaccine. You see, cowpox lymph, once inserted under the skin, can actually remain stable for a time and be carefully re-applied once the vaccine is complete to spread immunity. So Mohnike arranged for children from all over Kyushu to be brought to Nagasaki–working through the machi bugyo, or shogunally appointed city magistrate of Nagasaki, to do so. Once they were vaccinated–in the presence of Japanese doctors observing how to perform the procedure–they could then serve as carriers of the vaccine back to their own region where the vaccine could be re-applied and spread to other regions of the country.

The result was absolutely incredible. With the cooperation of major daimyo and the support of ranpo physicians who had studied the procedure carefully–aided by the re-discovery of Baba Saburo’s translation, which thanks to lords like Hotta and Abe was taken out of mothballs and used to train vaccinators–the vaccine spread rapidly around the country. Indeed, it turned out that despite Baba’s manuscript being unpublished, it or other tracts like it (like a text on vaccination translated by Sato Taizen in 1836) had been circulating in secret via hand-copied manuscripts. As a result, many ranpo physicians already knew how vaccination worked and were prepared to do the procedure.

The Stad Dordrecht and its vaccine shipment arrived on August 11, 1849; by the end of the year, vaccinations using its lymph were taking place as far away as remote outposts in the Kurile Islands or Sakhalin in the far north of the country. Dr. Mohnike himself vaccinated a few hundred children in Nagasaki (around 150 in the first few weeks), but estimated that by the end of the year thousands of children had been made immune to one of the great ravages of the age.

Of course, in a country with an estimated population of around 30 million at the time, that was just a drop in the bucket–though a fairly substantive one, at least.

None of this, by the way, took place with the official permission of the shogunate. In fact, just a few months before the start of this vaccination wave in 1849, the shogunate had actually banned the practice of Western-style medicine in its territory. That decision was driven by leading doctors at the shogunate’s official traditional Chinese school of medicine, the Igakkan, particularly its leader Taki Mototaka–the Taki clan had been the official physicians of the shogun since the 1750s and were concerned about losing influence to Western-style doctors.

Shogunal officials themselves were in no hurry to publicly embrace Western innovations, to be fair–after all, doing so would undermine a long-cherished institution of the shogunate: the policy of seclusion. Admitting, after all, that Western doctors had produced such an amazing innovation, and what’s more had done it over 50 years ago at this point, would raise some serious questions about what exactly the seclusion policy was accomplishing.

However, the shogunate did not actively discourage vaccination either; indeed, much of the 1849 arm-to-arm distribution took place in cities controlled by the shogun directly like Edo, Osaka, and Nagasaki itself. Reading between the lines, the decision seems to have been to maintain the law as it stood on the books, but not to enforce it–thus, if the vaccination went well, the shogunate could benefit from it, but it had plausible deniability if it went poorly–and the policy of seclusion could be protected. As Otto Mohnike, the doctor who started this vaccination drive, put it in one of his letters: “The central government at Edo is fully aware of the great importance of vaccination and secretly encourages its introduction but there still exists no official…policy for this. The government of Japan considers vaccination a foreign institution entering the country and therefore at odds with the policy of isolation.”

It wasn’t until the late 1850s that the shogunate began to actively encourage smallpox vaccination, for example funding a clinic in Hokkaido to vaccinate the local population. But most vaccination drives remained thoroughly private affairs–for example, a clinic opened up by Otsuki Shunsai on the outskirts of Edo next to the Buddhist temple Seiganji, known as the Otamagaike vaccination clinic. Initiatives like this received permission from the shogunate, but no government backing.

It wasn’t until after the end of feudalism and the establishment of the new Meiji imperial state that vaccination was made mandatory and given official government backing–a policy instituted by one of Ogata Shoan’s former students, Nagayo Sensai.

The results were impressive; in 1886 a smallpox epidemic resulted in 73,000 cases around Japan and just over 18,000 deaths; by 1905, a new epidemic saw only 10,000 cases and 3000 deaths. Smallpox would not be declared eradicated from Japan until the 1950s, but that work was clearly well underway.

So, what does this story offer to us? Well, for me, I think the most obvious historical lesson was the result of the seclusion policy. It’s indisputable to me that said policy massively delayed the advent of smallpox vaccination in Japan, an obviously beneficial procedure that has saved untold millions of lives. That seclusion policy was intended to protect the social and political balance that underlay the Tokugawa system–but as we’ve seen, it also stifled innovation and the adoption of obviously beneficial ideas. After all, it took 47 years from the first mention of vaccination in Japan to the first large-scale vaccination campaign!

Beyond this, the value of that network of ranpo physicians cannot, to my mind, be overstated. Perhaps it’s my memories of the pandemic influencing my thinking, but I see a lot of parallels in terms of the value of a network of people capable of making the case for vaccination and its value–and who are able to rapidly and swiftly deliver a lifesaving medical procedure when called upon to do so. The value of those professional networks–the ability to take pure knowledge and put into place the logistics to translate it to action–cannot be overstated.

Smallpox was, for most of our history, a scourge upon the earth. Its eradication is probably one of the greatest accomplishments of the modern era. But that path was not an easy one–and the people who walked it for us deserve all the recognition we can give them.

1. Were there any attempts at cultivating a domestic supply of Cowpox instead of having to rely on imports from the Dutch?

2. Amongst the daimyo who accepted vaccination who was more likely to do so: Fudai or Tozama daimyo? Was there any correlation between vaccine acceptance and where their clans lined up during the Meiji Restoration?

I recently finished the anime Hidamari no Ki based on the manga by Osamu Tezuka is about his great grandfather Ryoan Tezuka trying to set up a smallpox vaccination clinic in Tokyo while dealing with the kanpo practitioners blocking his every move to get funding, especially after ranpo was banned. Ryoan studied under Ogata Koan at Tekijuku and even met Fukuzawa Yukichi. It goes through a bunch of the big events of the Bakumatsu his great grandfather lived through, including the Ansei Purges, the Ansei Earthquake, and a great cholera epidemic he helped treat.

One of the biggest problems he faced was not only the blackmailing by the Koushougakuha, but the fact that people believed putting cow lymph in their bodies would turn them into cows.

The B-plot is about Ryoan’s fictional friend who is a shishi from Fuchuu domain. I mention this because he is assigned to be the bodyguard for Townsend Harris by Hotta Masayoshi, who you also mentioned.

Anyway, I think you’d like this show, even though I know you don’t watch anime.