How did one man’s determination to get paid end up producing one of the best records we have of a pivotal moment in Japanese history?

Sources

Conlan, Thomas. In Little Need of Divine Intervention: Takezaki Suenaga’s Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions

Yamamura, Kozo, ed. The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 3: Medieval Japan.

Princeton University’s website on the scrolls, which has some cool contextual information and detail shots.

Images

Transcript

Today, I want to tell a story about one of the most unique sources I’ve ever encountered, and what we can learn from it about an often misunderstood period of Japanese history.

The source in question is the Moukou shuurai ekotoba, roughly ‘Illustrated Account of the Mongol Invasion’, which is more or less what it says. There is an excellent translation out there in English, produced by Dr. Thomas Conlan–and if you’re at all interested in the period, I highly recommend checking it out.

First and foremost, we should probably refresh ourselves on the Mongol invasions of Japan. So–some time around 1162, a boy named Temujin was born to Yesugei, a chieftain of the Borjigin clan of Mongols, a nomadic people eking out an existence on the Eurasian step.

Temujin’s early life is not well documented; what we have comes from substantially later sources that are of dubious accuracy. We can be fairly certain, however, that by the 1190s Temujin had succeeded in unifying most of the Mongol tribes under his leadership–within the next few years, he defeated major rival step tribes in the form of the Tatars, Jurkins, and Naimans. As a result, in 1206 he was proclaimed Chinghis Khan, roughly ‘universal ruler’, by his fellow Mongols.

Most of us, I imagine, are familiar with what comes next. By the time the great Khan himself died in 1224, he already ruled over a massive empire forged by the military prowess of Mongol horsemen–and by his own carefully refined approaches to tactics and to military organization. That empire stretched from northern China well into central Asia, and his forces had already begun raiding places further afield.

The Empire would reach its zenith under the fifth khan, Khubilai–who himself ruled from a new city called Khanbaliq, or Dadu in Chinese, though it’s better known today as Beijing. Ultimately, it was under Kubilai’s rule the empire began to come apart, as its sheer size combined with the frequency of succession disputes necessitated the division of the empire into four successor states (of which Kubilai’s chunk, the Yuan dynasty of imperial China, was the wealthiest). Those successor states would in turn either implode or be overthrown over the next 100ish years, though surviving successor states would continue on for the next few centuries.

But anyway; it’s Kubilai’s rule we primarily have to concern ourselves with. Kubilai saw himself as inheriting his grandfather Chinghis Khan’s charge to bring the whole of the world under his rule. It was during Kublai’s reign that the Mongol conquests of China, which took decades of hard fighting, were completed. He was also responsible for subjugating the rulers of the Goryeo dynasty, at that time the kings of Korea. And then, of course, he turned his attention to Japan.

Japan, at this time, was governed by what I think it is fair to call one of the oddest geopolitical arrangements both in Japanese history or possibly ever. Nominally, of course, power rested in the hands of the emperor in his capital at Kyoto; at the time Kublai first began to threaten Japan in 1266 CE, that’d be the 17 year old emperor Kameyama (who has come up before; he’s one of many people Lady Nijo, the subject of episode 454, had an affair with).

But of course, Kameyama didn’t actually do that much governing, and not because he was too busy having affairs–because for several centuries at this point, the emperors had been reduced to figureheads controlled by the aristocratic families of Kyoto. Young emperors were propped up either by aristocratic families like the Fujiwara, or by their own relatives–retired emperors who stepped down from the throne to call the shots from behind the scenes.

Except that by the 1200s those people weren’t even calling the shots anymore, at least not fully. By about 1000 years ago, the warriors of the samurai class, first given independent fiefs and chartered to fight the Emishi natives of northern Japan, had begun to assert their own political independence against the Kyoto government. In the late 1100s, one of those warrior families, the Minamoto, had risen above all the others to become the unquestioned rulers of the samurai class.

The Minamoto family head, Minamoto no Yoritomo, was in turn able to force the Kyoto aristocracy to revive for him an ancient title–sei’i taishogun, or supreme general for the subduing of barbarians, essentially the commander in chief of the samurai class. Once upon a time used as a temporary title for those commanding forces against the Emishi, the position of shogun would now empower the Minamoto family to act as military governors of Japan.

They weren’t the sole government, mind you; instead, the new structure would be a parallel one. The old civilian government in Kyoto would continue to operate, appointing kokushi, or provincial governors for Japan’s 60 odd provinces. Alongside these men would serve the shugo daimyo, military governors apponted by the shogun. The job of the shugo was to handle security affairs, banditry, keeping their fellow samurai in line–things like that, to operate alongside their civilian counterparts.

In practice, the shugo were constantly pressing up against the authority of their kokushi civilian counterparts, and over the course of the next several centuries would slowly undermine their authority, independence, and power. They never dispensed with the imperial system, in large part because the leading members of the warrior class traced their ancestry back to that same aristocracy (or in some cases the imperial court) and relied on it for their own legitimacy–but they were not always deferential to it either.

Speaking of slow undermining; by the 1260s, the Minamoto clan was no longer calling the shots in their own new government–called the Kamakura shogunate, after the city of Kamakura in remote eastern Honshu where the Minamoto base of power lay. Indeed, the Minamoto clan itself no longer existed by the 1260s; it was wiped out by a combination of infighting and assassination among both its own members and its follower families.

In its place had risen the Hojo clan, which had been one of the primary allies of the Minamoto during their rise to power. The Hojo, however, lacked the aristocratic pedigree to assume the title of shogun themselves, and instead installed a series of young (and I do mean young) imperial princes as shogun while ruling themselves as the shikken, the shogun’s regent.

So in summary, we have a shikken from the Hojo clan ruling on behalf of a shogun from the imperial family ruling on behalf of the Kyoto aristocracy ruling on behalf of the emperor. Politics gets wild sometimes.

Anywho, it was into this whole arrangement that Kublai Khan’s first threats to the Japanese began to arrive. Starting in 1266, the Khan dispatched messages to Japan’s rulers via Korean intermediaries calling on Japan to submit to Mongol rule. The language, influenced by Kublai’s interest in Chinese Confucianism, was couched in the traditional pleasantries asking the Japanese to send ambassadors to recognize Kublai’s ascension to China’s imperial throne. However, the threat was quite clear; Japan would have to accept status as a Mongol vassal state, much as other powers in East Asia had in the past accepted vassal status from China. If not, an invasion would be coming.

The demands for submission were ignored, and in 1274 an invasion force was dispatched from Korea for Japan. Which brings us to the Moukou Shuurai Ekotoba, and the man behind their creation: a samurai by the name of Takezaki Suenaga.

Unfortunately, we know little of Suenaga’s origins or his life before the Mongol campaign. His date of birth is often given as 1246 CE, because of a document he commissioned in 1293 which describes him as being in his 48th year (by the traditional Japanese reckoning, where you’re one at birth). He was of samurai status, from Higo province in Western Kyushu (now more or less Kumamoto Prefecture after the administrative reorganizations of the 1870s).

Specifically, he held the status of a gokenin, a complicated but important term for a member of the samurai class. The status of gokenin, roughly “honorable man of a household”, was one that first emerged in the final decade of the 1100s as a part of the creation of the Kamakura shogunate. Specifically, gokenin status was handed out to those who openly pledged themselves to the Minamoto (or to their shugo daimyo representatives in the provinces) and who could call upon a small fighting band of their own followers. And I do mean a small band–low to mid single digits, usually.

Gokenin were, in essence, vassals–formalized for the first time under the control of the shogunate, where in the past those ties of loyalty had been more personal and based on the individual charisma of a ruler. Now, those bonds were formalized, tracked by a sort of contract between gokenin and the local representatives of the shogunate. Under the Kamakura shogunate, gokenin status was for the first time actually tracked–gokenin had to register with the local shugo to be fully recognized in their status. This was the start of an actually organized feudal army–shugo were mobilized by the shogun, who mobilized their gokenin, who gathered up their followers to assemble an armed force.

Takezaki’s ancestors had presumably pledged themselves as gokenin 80 years earlier during the earliest years of the shogunate, in exchange for which they were confirmed by the local shugo daimyo with control of their ancestral residence in Higo and perhaps some land rights nearby. How much land is unclear, but gokenin grants were never exactly vast.

The chief payment for gokenin in these early years, however, was not land rights but rewards for prowess in battle. Samurai armies of the medieval era were still funded primarily off plunder, which would be handed out in turn to warriors on the winning side based on treasure from the defeated–as determined both by a warrior’s individual contribution, as well as their valor and accomplishments in the fight itself. This is why Takezaki took such great care to track what he did in the fighting, with said notes in turn becoming the basis for the Moukou Shuurai Ekotoba scrolls themselves.

And I should note before we get into it that the text itself is unfortunately incomplete. The Takezaki family will not endure forever; it was wiped out in a later series of civil wars in the 1300s (the wars of the Northern and Southern imperial courts, if you know the time period). After the end of the Takezaki family, the scrolls would end up in the hands of another warrior family–who would neglect them until the 1700s, when they were rediscovered.

Missing images or illustrations were still being rediscovered in the early 1800s. As a result of about 4 centuries of neglect, chunks of the text are damaged or missing, complicating the reconstruction of Takezaki’s life even further.

Anyway: The scrolls themselves begin in media res, so to speak, in 1274. A Mongol warfleet–composed at this point mostly of conscripts from other ethnic groups, particularly Koreans, given how far the empire has expanded and the fact that the Mongols themselves were not exactly renowned seafarers–has arrived in Japan. That fleet has already overrun Tsushima in the middle of the straits separating Korea and Japan, as well as Iki island off the coast of Kyushu. Now, Mongol forces have landed outside Hakata (now Fukuoka), the nerve center of the shogunal government in Kyushu.

The narrative describes Takezaki as almost chomping at the bit for a fight–and given the importance of demonstrating courage for his own standing as a warrior, you can see why he might be. The narrative opens with word coming to Higo of the izoku–literally “barbarian bandits”, in other words, the Mongols–appearing off the coast. Takezaki and his fellow Higo warriors, marshaling themselves for a fight (and swapping around their helmets so they can recognize each other in a fight and attest to each other’s valorous deeds) then encounter one of the commanders of the Japanese defenses, Shoni Kagesuke. There he and four of his followers from Higo who have accompanied him are told to dismount–the Japanese forces are going to set up in a fortified position and ambush the Mongols with arrows. Takezaki, however, is not having it, “”We five horsemen are going to fight before you. We won’t limit ourselves to merely shooting down the enemy! I have no purpose in my life but to advance and be known. I want [my deeds] to be known by his lordship [Shoni Kagesuke].”

This obsession with being seen as a warrior repeats throughout the text. Literally the very next moment of narration describes Takezaki on the way to the battle; he passes by one of the major shrines in the region (Sumiyoshi Shrine in Hakata), and there encounters another warrior returning from battle with the severed heads of Mongol foes. His response to seeing someone appearing “so brave” (his words) is to redouble his own efforts to go on the attack.

Unfortunately, Takezaki was late for the fight. By the time he arrived on scene, the Mongols had already attempted an initial landing at Hakata bay in Northwestern Kyushu, and been driven into retreat. Their forces had retreated westward to the area of Torikai beach to the west of the city of Hakata (now Fukuoka, the center of shogunal government in Kyushu. Still, he was in time to take part in the next battle, and still have a chance to win glory.

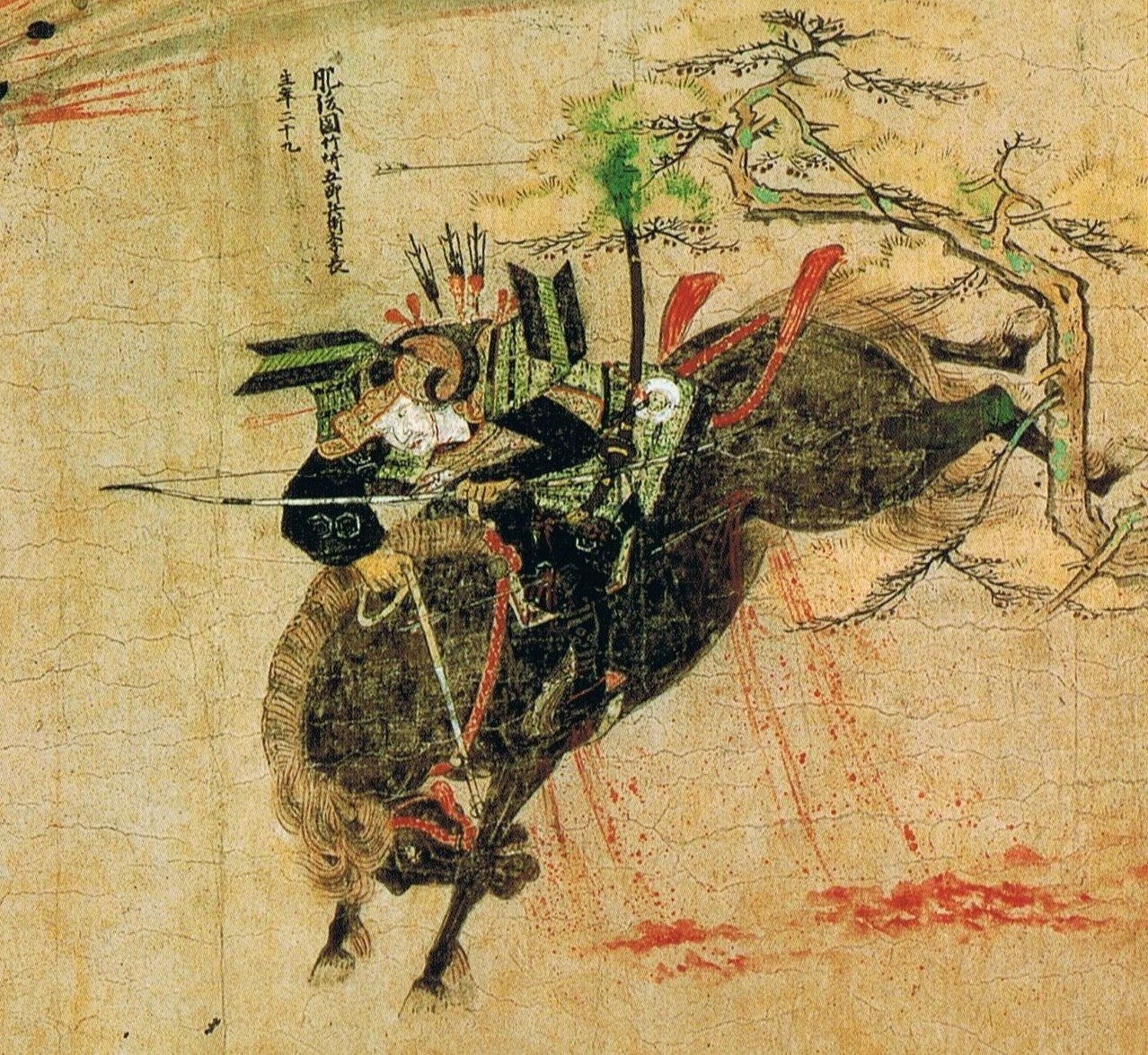

Thus comes the first battle scene: “The invaders established their camp at Sohara and planted many battle flags. Shouting a battle cry, I charged. As I was about to attack, my retainer Sukemitsu said: “More of our men are coming. Wait for reinforcements, get a witness and then attack!” I replied: “The way of the bow and arrow is to do what is worthy of reward. Charge!” The invaders set off from Sohara and arrived at the salt-house pines’ of Torikai beach. There we fought. My bannerman was first. His horse was shot and he was brought down. I Suenaga and my other three retainers were wounded. Just after my horse was shot and I was thrown off. Shiroishi Rokuro Michiyasu a gokenin of Hizen province, attacked with a formidable squad of horsemen and the Mongols retreated toward Sohara. Michiyasu charged into the the enemy, for his horse was unscathed. I would have died had it not been for him. Against all odds, Michiyasu survived as well, and so we each agreed to be a witness for the other. Also, a gokenin of Chikugo province, Mitsumoto Matajirō, was shot through his neck bone with an arrow. I stood as a witness for him.”

You might be wondering what ‘witnessing’ means in this context. It has to do with tracking battlefield accomplishments of specific samurai, because remember that’s a big part of their pay (so to speak). A witness could attest to things like your bravery in battle, whether you were among the vanguard in an attack, how many enemies you had killed (especially if you had not managed to take any heads, the common method of proving one’s accomplishments. The more (and more credible) witnesses you could offer for your accomplishments, the better in terms of your ability to make your case for compensation.

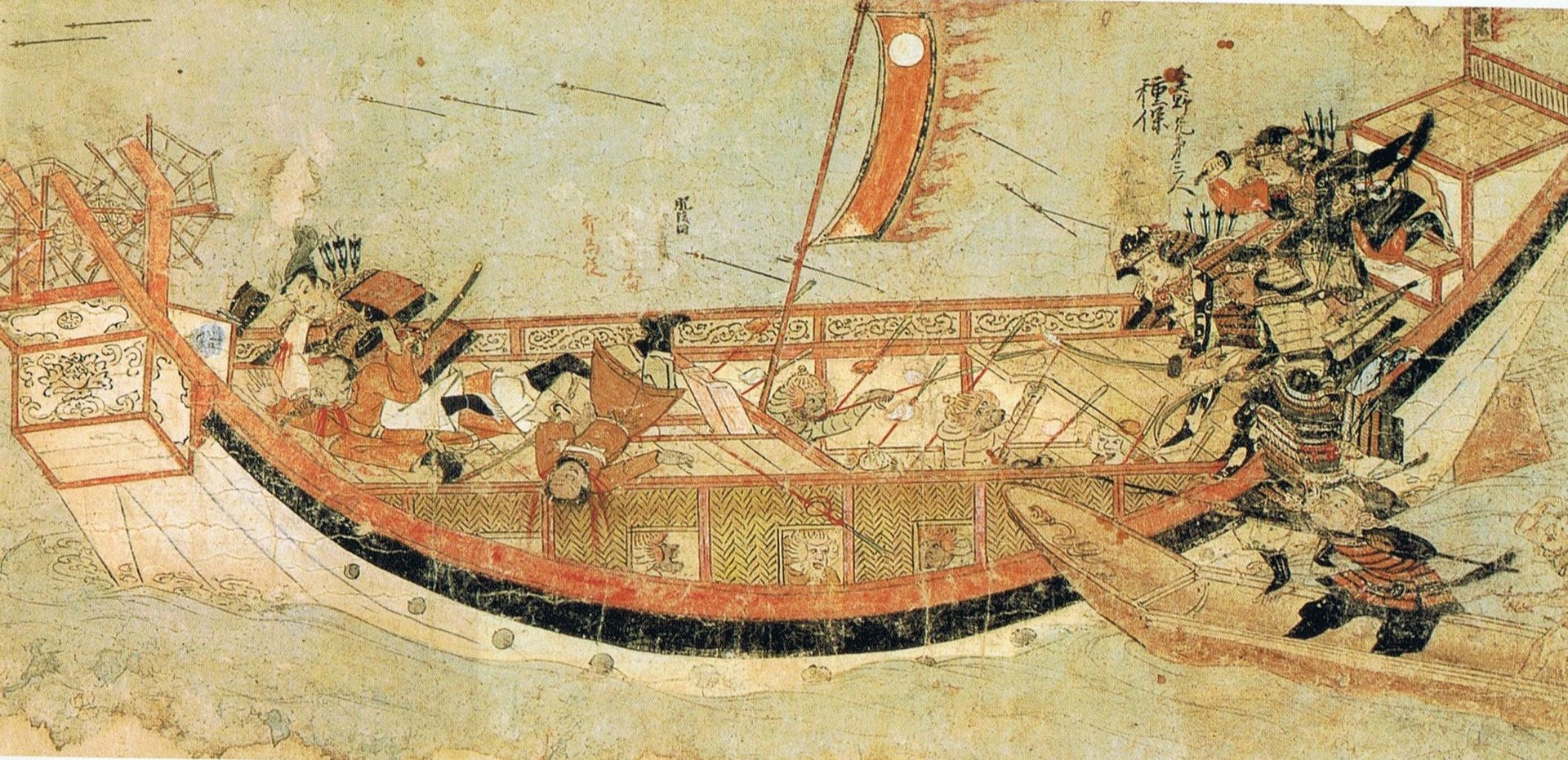

As valuable, if not moreso, than Suenaga’s own account of the battle are the illustrated depictions that accompany it–because remember, this is an ekotoba, an illustrated account, not just text. The illustrated scroll is dated to 1293, so a bit over a decade after the second and final Mongol invasion of Japan and well within living memory–because of that, it’s an invaluable source for knowing what that invasion looked like, so to speak. For example, the illustrations provide lavish account of how the samurai comported themselves; they’re how we know that Takezaki’s commander, Shoni Kagesuke, had a saddle with a tiger skin pattern on it (presumably intended to show off his great personal valor and high status).

There are also several images of Mongol soldiers, primarily infantry–giving an excellent source on the design of the weapons and armor they used. I’ll include a couple of images in the show notes; there’s also a complete scan of the scrolls with some great explanatory notes available online that I will provide links to.

The scrolls then conveniently jump to the aftermath of the departure of the Mongols, a lacuna perhaps best explained by the fact that the actual battle on Torikai Beach was a defeat for the Japanese–the Mongols waited until the Japanese forces moved into position to attack, and then struck first while the Japanese were still getting themselves organized. The result was a rout, after which Japanese forces retreated 10 miles southeast to fortified positions and let the Mongols range over Hakata and the surrounding area to loot.

Shoni Kagesuke counted, correctly, on the fact that his forces were still together even if they had been defeated, and that the Mongols, tired and bloodied, would decide to pull back onto their ships once it became clear they couldn’t win outright. Otherwise, they risked more Japanese reinforcements showing up. And so the Mongols retreated to their ships–and what came next, of course, was a typhoon, the kamikaze, that swept the invasion fleet away.

Takezaki’s account, however, does not mention this at all. It skips directly from the account of the battle (in the late fall of 1274) to the sixth lunar month of 1275 (the late summer). Takezaki has survived being shot off his horse, but despite that stroke of good fortune he’s not what you’d call happy.

You see, in the aftermath of the victory, the local authorities of the shogunate in Kyushu had begun to parcel out rewards–the common practice of the time, because remember a big chunk of how warriors were compensated was for their accomplishments in victorious battle. And Takezaki, in the end, did not do great out of that process.

After the battle, the local shugo daimyo would write letters back to Kamakura documenting the bravery (or lack thereof) of their gokenin based on the available witnesses and other evidence. Rewards were then distributed by the shogunate back in Kamakura based on the reports.

However, there were a LOT of reports and not a lot of rewards–because remember, there was no plundered land and (given the whole sunk Mongol fleet thing) not much treasure to distribute. And so the returns from those petitions were not what a lot of warriors, including Takezaki, wanted.

Takezaki’s response to this disappointing turn of events was to simply go to Kamakura himself and try to rectify the situation by pleading his case with the shogun’s officials. Having decided on this course of action, he left early in the sixth lunar month of 1275 to begin his journey (which would take two months to complete). That turned out to be smart of him; just a few months later, the Kamakura shogunate would issue new orders assigning Kyushu’s gokenin to build fortifications in preparation for another invasion, preventing any of them from going to request more rewards in person.

Some attempted to petition for more rewards by writing letters; we have one such, from a samurai from neighboring Bungo province, Tahara Yasuhiro, who sent a letter east in hopes of having his rewards increased (he was not successful).

This is getting a bit ahead of ourselves, but in the aftermath of the second invasion the shogunate would attempt to head off the issue of all its warriors ditching Kyushu to go argue for more pay by setting up a sort of local court in Kyushu itself to hear petitions on the subject.

Anyway; none of this applied to Takezaki, who was able to make his way east to Kamakura. And I don’t want to make it seem like what he did was somehow obvious–he was taking an enormous risk by doing this, particularly because, since his petition to the shogunate was not a part of his official duties, he had to self-fund it and was not exactly rolling in cash. Indeed, he had to sell his own saddle and horse to cover the travel expenses, and given that samurai were mounted warriors at this time that meant he was taking an enormous risk. If his plea was not accepted, he would literally be unable to do his job in the future.

However, once he got there in the fall of 1275, he quickly ran into a different problem–given his low status and small entourage (just a two footmen named only as Yasaburo and Matajiro), nobody wanted to meet with him.

Eventually, however, he was able to secure a meeting–Takizaki claimed it was due to divine intervention after praying at Kamakura’s main shinto shrine, Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, but more likely it was because he refused to stop annoying the Kamakura leadership until somebody would talk to him.

Specifically, after a great deal of annoying prodding of shogunal leaders (he got there on the 12th day of the 8th lunar month, and this took until the 3rd day of the 10th lunar month) he was able to secure a sitdown with Adachi Yasumori.

Yasumori was technically his boss–the shugo of Higo province, appointed some time between 1272 and 1274–but, like most of the shugo, he didn’t want to go to some far off backwater like Higo, remote from the center of power. Instead, he’d remained in Kamakura and relied on jito–stewards–out in the province to manage things for him. The fact that he was both fairly new as a shugo and had been given a low-ranking province like Higo also probably helps explain why Adachi was willing to sit down with someone like Takezaki.

Adachi, in turn, is central to Takezaki’s narrative. Initially, he was hesitant to offer more rewards to Takezaki, noting that Takezaki had not taken the heads of any famous Mongols and accomplished little more in terms of concrete action than losing a horse and getting himself injured. Why, he asked, should he be rewarded for that?

Takezaki countered that he had several witnesses to his valor to supplement his report, and eventually badgered Adachi (in a very respectful way) into agreeing to both forward a recommendation he be rewarded and passing word of his deeds up to the shogun.

Considering that the scrolls are depicting an event from several decades prior here, and the fact that this is something Takezaki commissioned (and therefore he’d want it to paint him in a good light) we should view the recollection of this conversation contained in the scrolls with a bit of skepticism. I’m not sure I totally believe, for example, that Takezaki demonstrated incredible sincerity by volunteering himself for a beheading if his reports of his actions were found to be untrue. But in broad strokes, it’s pretty believable that Takezaki was willing to go to such lengths to secure recognition for himself; after all, it was literally his livelihood at stake. Or, to use the florid language of the text, “other than advancing and having my deeds known, I have nothing else to live for.”

Though the scrolls Takezaki commissioned are justifiably more famous for their visual depiction of the fighting against the Mongols, this is actually by far the most detailed part of the entire account in terms of text. A lot of attention is paid to the verbal back and forth between the two men, far more than the descriptions of the battles against the Mongols.

It’s not hard to understand why, however, because that audience proved to be the turning point of his life. The very next day, Takezaki heard from a friend in Kamakura that Adachi had been telling his own retainers about, “a warrior of unusual strength of will” and recommended him to receive more reward for his service.

It apparently took about a month to kick that request up the chain, but on the first day of the 11th lunar month, Takezaki was summoned back and handed an edict confirming some new land rewards for himself–specifically, a role as jito, or steward, of Kaito district in what’s now Kumamoto. He was also gifted a chestnut horse with a new saddle, ensuring that in the future he’d be able to return to the frontlines.

The account then skips ahead to 1281, when the forces of Kublai Khan made another go of an invasion of Japan. Once again, the Mongol plan was to advance on Tsushima and the other outlying islands of Kyushu, and to drive straight for Hakata to take out the shogunate’s headquarters on the island. This time, however, they’d be able to do so with a far larger army. Numbers given from contemporary accounts should not be trusted–the official history of the Yuan Dynasty says the Mongol army was over 100,000 strong, while a Kamakura era source says 150,000. Thomas Conlan, one of the best writers on this period, gives a far more reasonable estimate of around 10,000 Mongols against a few thousand Japanese defenders. It seems reasonable that the 2nd invasion was larger than the 1st, however, because by this point Kublai Khan had finished off his other major geopolitical rival in the form of the remnants of the old Song dynasty of China. Thus, he could direct a far larger force against Japan.

However, the Japanese had also now had seven years to prepare for a second invasion, and Hakata was now fortified with substantial stone walls–not to mention battle hardened veterans of the first invasion.

This time, the Mongols would not even make it onto Kyushu proper–their advance would stall on the outlying islands, while Hakata itself remained unscathed. Instead, the fight would primarily be at sea, with Japanese forces on boats skirmishing against the Mongols and attempting to harass their ships docked in the harbors of those conquered outlying islands.

Once again, the narrative of Takezaki’s scroll picks up right in the middle of things, jumping directly from the conclusion of his meeting with Adachi to him on the way to fight in 1281. In the interests of time, I won’t spend too much time on this, both because it’s fairly similar to the first battle scene and because (at least to me) the most interesting bits are easy to sum up.

Simply put, Takezaki is once again almost suicidally brave in his pursuit of glory, even going so far as to lie to other samurai about his orders in order to get a spot on a boat headed for the frontlines. This, however, doesn’t really count against him–indeed, it so impresses one of his colleagues that he refers to Takezaki as dai mouaku no hito, a phrase Thomas Conlan translates as “the baddest man around.” Which now really makes me want a photoshop of the scrolls but with Takezaki’s helmet stamped with BAMF. But I digress.

Anyway: the text ends with a final recollecting of the battle and Takezaki’s involvement in it. Once again, there’s no mention of the role of a typhoon in wiping out the Mongol fleet–just as had happened in 1274–but that’s not too unusual. After all, the role of this whole narrative is to recount Takezaki’s accomplishments and good fortune, and the role of mother nature in the battle is not a part of that story.

Instead, there’s a final section once again praising Adachi Yasumori, and an ending recollection where Takezaki credits his enormous good fortune in life to the intervention of the deity of Kosa Shrine in Kumamoto, Kousa Myoujin, whose shrine is in the Kaito fief Takezaki served as the steward of.

After this point, our knowledge of Takezaki becomes pretty thin. By the time the scrolls themselves were commissioned in 1293, he’d set up a family temple for himself, Toufukuji (which is still in Kumamoto), and become a lay monk (having taken the Buddhist name of Houki (roughly, “rejoicing in the dharma”). He was still alive by 1324, because we have an edict from him announcing new donations to support Kousa Shrine–but after that point, his fate is unknown.

So, what can we make of this little story–which on the one hand is a fascinating tale of one man’s experience during one of the most momentous events in medieval Japanese history, but on the other represents a guy essentially represents a bureaucratic battle over pay?

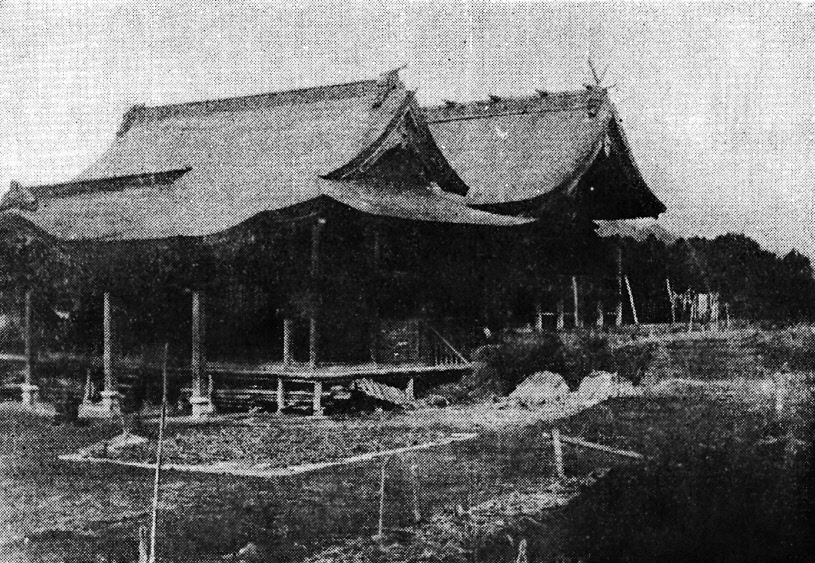

Well, there are a few things we can take from this tale. Takezaki, for one, has become something of an interesting figure in his own right because of the window his story provides us into the lives of gokenin, not usually the primary focus of period documents more focused on the upper levels of the samurai class. Takezaki himself became something of a symbol during the imperial era, for example, of the martial valor of the samurai; a monument erected on what’s supposedly his gravesite in the early 20th century has calligraphy from one of the great war heroes of Imperial Japan, Togo Heihachiro, of a quotation from the text about Takezaki’s devotion to the way of the warrior. The government even opened a Takezaki Shrine in the 1930s as a way of promoting its militaristic ambitions, but the shrine fell apart in the 1960s and was never repaired.

More recently, Takezaki still figures into depictions of the era; from what I can gather, his last on-screen appearance was in 2001, in one of NHK’s historical Taiga dramas about the Mongol invasions. More important, however, than Takezaki himself (at least in my view) is what he left behind. The Moukou Shuurai Ekotoba scrolls are an incredible source for information about war and samurai culture in the 1200s–though there have been changes to the scrolls over time, and reconstructing the originals can be a challenge. Still, the images the scrolls contain showing everything from the shape of Japanese defenses against the Mongols to the kind of weapons both sides used to what an audience with a senior member of the Kamakura shogunate’s leadership looked like are invaluable to historians.

Indeed, the English translation of the scrolls is central to Thomas Conlan’s famous essay where he advances a crucial argument about our understanding of medieval Japan–that, in fact, Japan’s victory against the Mongols was not a matter of luck or divine providence in the form of the typhoon winds known as kamikaze that twice swept their fleets away.

Admittedly, when I was in school, the Mongol invasions were well out of the period of Japanese history I was specialized in, but that was certainly the story I got–that the victory of the Kamakura shogunate over the Mongols was a matter of luck.

Instead, says Conlan, scrolls like the one Takezaki left behind show the sophistication of Japanese warriors and the quality of their tactics and training–they were, to use the title of his essay, “in little need of divine intervention” to win the day.

Takezaki wanted his deeds to live forever–and in a certain sense they have. His accomplishments and his decision to record them have provided us with an invaluable window into a crucial moment in Japanese history. His deeds are known, and his name lives on.