This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: Japan joins the ranks of the great powers by building its own colonial empire. How did Japan come to be a great colonial power, what made its empire different from the others of the age, and more importantly: what made it the same?

Sources

Iriye, Akira. “Japan’s Drive to Great Power Status” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol V: The Nineteenth Century

Drea, Edward. Japan’s Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1867-1945

Cummings, Bruce. Korea’s Place in the Sun

Kang, Hildi. Under the Black Umbrella: Voices from Colonial Korea, 1910-1945.

Caprio, Mark. Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945.

Peattie, Mark R. Nan’yo: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945.

Shigeaki, Shiina. “Outline History of the Colonization of Hokkaido, 1870-1930.” in Migrants in Agricultural Development. Ed. J.A. Mollett.

Mason, Michele M. Dominant Narratives of Colonial Hokkaido and Imperial Japan: Envisioning the Periphery and the Modern Nation-State.

Images

Transcript

The last two weeks have been about Japan after the end of feudalism, and the country’s struggle with modernity–with figuring out what strengthening Japan meant in terms of balancing the demands of tradition and change in the fields of politics, economics, and society.

But there’s one thing we haven’t talked about which, in the 1800s, was viewed as an integral part of modernity itself. All the Great Powers of the West–and many of the minor ones too–had empires, and the pursuit of empire was considered part and parcel of what made modernity, well, modern.

Empire, of course, has a long history in Europe, America, and also everywhere else–and the conversation around what made the empires of the 19th century West different from those of the past (or even how different they were) is an interesting academic conversation we don’t really have room for.

One thing that was distinct about most 19th century Western empires, however, was their focus on economics. Western empire during the Victorian period was driven primarily by economic rationales–for example, this was why France, Germany, and the UK carved out exclaves from China at gunpoint, so that those territories could become a base for a push into the China market.

That wasn’t true of every imperial acquisition of the period–Germany, for example, snapped up control of Micronesia in the West Pacific not for economic reasons but simply because its leaders did not want to feel they’d been left behind in the scramble for Asian colonies. And of course, there were older established colonial ventures in place–the British hold over India, for example. But in terms of the rationale of empire, the argument for it–that was largely economic, when it wasn’t being couched in the language of the so-called “white man’s burden” to “civilize the world” (I cannot possibly put enough quotes around that).

And I mention this because as we look at Japan’s empire, we’ll see something very different. Japan’s overseas empire absolutely had an economic component–and there was even language of “civilizing” the locals that would have been very familiar to colonial overseers from Britain or France. But the argument for empire was made, first and foremost, in military terms.

Indeed, arguably Meiji Japan’s first conquests were Hokkaido and the Ryukyus–both of which had been loosely attached to the shogunate but still independent in a sense. That ended in the Meiji Period; Hokkaido was formally annexed in 1869, and a colonization office set up to ship settlers over to the island (mostly from the defeated side of the Boshin War; this is also why Hokkaido dialect is very close to standard Japanese, because it’s comparatively new).

The Ryukyus, meanwhile, were formally annexed in 1878, with a government program of forced assimilation of the natives being put into place–replacing the Ryukyuan language with standardized Tokyo-dialect Japanese, for example.

The rationale in both these cases was that Hokkaido and Okinawa were necessary to protect the home islands–they could not be allowed to fall into the hands of potentially hostile neighboring powers like Russia.

The same rationale justified the 1st Sino-Japanese War–the first of Japan’s overseas colonial wars. And it was very much a colonial war, intended to secure Japanese domination of Korea away from another regional power, China.

More or less from the advent of the Meiji Period, Japan’s relations with Korea had become increasingly tense. Korea’s Confucian monarchy was deeply conservative, and rejected all attempts by Western powers to force an end to their seclusion laws (which were quite similar to Japan). Japan was actually the first country to force Korea to sign an unequal treaty in 1876, making use of the nascent power of the Imperial Japanese Navy to threaten the Koreans into agreeing.

By the 1880s, Japan had an extensive sphere of economic and political influence in Korea, bolstered by a faction within the Korean government who supported Meiji-style reforms within Korea itself. Japanese interest in the peninsula was driven primarily by military reasons; as Jakob Meckel, the German staff officer who trained Japan’s first general staff, put it, Korea was a dagger pointed square at the heart of Japan, an ideal jumping off point for any power planning to invade Japan itself.

However, Japan was not the only power with a colonial interest in Korea. In the aftermath of the Taiping Rebellion, the Qing dynasty of China had entered a period of revival and increasing assertiveness, and its historically close relationship with Korea made it a growing influence on the peninsula. In addition, factions of the Korean government supported a close relationship with Imperial Russia, the third major power in the region and a potential counterweight (so the thinking went) to Chinese and Japanese influence while also providing a valuable source of industrial and technological knowledge.

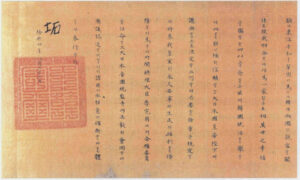

Over the course of the 1880s, relations between these three powers over the question of Korea became increasingly tense, but never directly hostile–Japan and China in particular signed the convention of Tianjin, demilitarizing the peninsula and promising that each would inform the other if their forces were ever dispatched there in order to lower tensions. This worked for a time, but eventually the Japanese leadership decided to make a play to drive China from the region and seize Korea for itself–especially once attempts to seize control of Korea by other means, for example supporting a pro-Japanese coup in 1884, failed.

The impetus for war came in 1894, with the beginning of a peasant uprising in Korea known as the Donghak movement. Donghak, in Korean, means “Eastern Learning”; the Donghaks were both a political and religious uprising among Korean peasants callign to rectify the ills of Korean society by returning to traditional Korean values. The rebellion was substantial enough that the Korean king, Gojong, sent to Beijing requesting Chinese reinforcements to put the rebellion down–something that had happened in the past, thanks to the longstanding relationship between the two countries. The Chinese happily acceded, and informed Japan of their plans to dispatch forces per the Tianjin agreement.

Here, at last, was the moment of opportunity; in Tokyo, the political leadership decided to take a risk and seize their chance to drive China out of Korea once and for all. A crisis could be manufactured here; the Japanese government claimed it had never received any notification from China regarding its forces, and began to mobilize. And on July 25, 1894, Japan declared war.

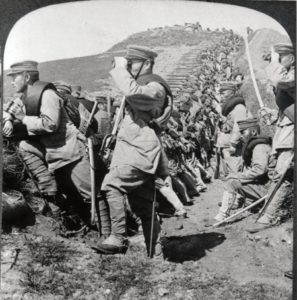

Outside observers were generally not too sanguine about Japan’s chances; after all, the country was massively outnumbered by Chinese forces, and the most direct opponents of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy were China’s Beiyang Army and Navy, some of the most modernized elements of the military. By contrast, Japanese forces were untested in a conflict of this scale–not to mention the logistical challenges of moving large numbers of men on slow, vulnerable troop transports onto the Asian mainland.

Despite these pessimistic forecasts, the war was a decisive victory for Japan. Japanese forces swiftly moved to Seoul and seized control of the Korean throne, and then drove the advancing Chinese forces out of Korea with ease. On land, the Imperial Japanese Army swept aside the Chinese, pushed across the northern Korean border into Manchuria, and from there continued to advance, winning every battle along the way. On water, Chinese fleets were decisively crushed by the Imperial Navy in the Yellow Sea. Japanese invasion forces landed both on Taiwan and on the Shandong Peninsula opposite Korea, seizing the former island and defeating a massive Chinese garrison at Weihaiwei on the latter.

The war ended in April of the following year with a crushing Japanese victory. China was forced to accept both a loss of its sphere of influence in Korea and Japanese seizure of Taiwan, as well as the Liaodong peninsula north of Korea. China was also forced to pay a cash indemnity to cover the cost of the war. Meanwhile, Japan suffered just over 1000 combat deaths in total–far more men were lost to disease caused by lack of hygiene and disease on the march than in battle. China, meanwhile, saw its most advanced armies and fleets crushed–one of the flagships of its new modern fleet, the Zhenyuan, was captured by the Japanese and recommissioned as an Imperial Navy warship. Japan had won its first colonial war in decisive fashion.

In the aftermath of the conflict, Korea became a colonial dependency of Japan, with its monarchy subject to Japanese “advisors” who largely ran things from behind the scenes.

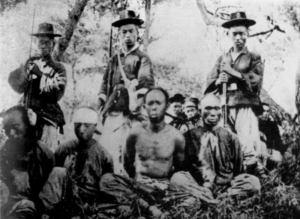

Fifteen years later, Japanese leaders would drop all pretense and formally annex Korea into the Japanese Empire. The next half century of colonial rule on the peninsula would see brutal mistreatment of the Korean people, whose language and customs were suppressed in the name of “Japanization” while their people were exploited with extractive taxation–and attempts at political dissent were brutally and violently crushed. A similar fate awaited Taiwan, where particularly brutal treatment was dolled out to aboriginal tribes that resisted Japanese rule, including aerial bombings with poison gas.

While the war was a military success for Japan, its political ramifications were far more mixed. In particular, Japan was shortly faced with a demand from Russia, backed by Germany and France (both of which were more interested in an alliance with Russia than in good relations with Japan) demanding that the Japanese return the Liaodong Peninsula to Chinese rule. Ostensibly, the demand was intended to ensure China was not punished too harshly or destabilized by defeat; in practice, this was a cynical play by the Russians, who wanted the Liaodong Peninsula for themselves and knew they had a better chance of forcing the Chinese to lease it to them than taking it from the Japanese.

This Triple Intervention, to which Japan was forced to accede, sparked intense nationalist furor and was a major impetus towards war with Russia a decade later. And that war, in turn, drove an increasingly destructive dynamic in Japanese policy.

Korea, over the years, would become an incredibly valuable colony for Japan–so much so that right up to the end of the Second World War, one of the major sticking points in terms of ending the conflict was a desire among the political leadership in Tokyo to hang on to the peninsula.

And that, in turn, meant that a desire to secure Korea–the southern tip of which was transformed during the colonial period into a breadbasket for the empire, while the north was industrialized to help defend the colonial frontier–ended up driving the exact same military dynamic which had led to the invasion of Korea in the first place.

The clique of Meiji autocrats had believed they needed Korea to keep Japan safe, and the Liaodong Peninsula had to be fortified to protect Korea. Once the Liaodong Peninsula was secured from Russia, the thinking became that control of all of Manchuria was necessary to secure the peninsula, and then that control of China and the Russian Far East was necessary to secure Manchuria. Expansion was driven by paranoia that others might seize what Japan did not, as well as by greed and a desire for ever greater wealth for the empire. And that mindset–intended to protect the empire–ultimately led squarely to its destruction in World War II.

But we’re a ways from that yet, and there’s one more colonial war to talk about first. You see, more or less immediately from the conclusion of Japan’s war with China in 1895, it was obvious that war with Russia was on the horizon. The Triple Intervention, spearheaded by Russia alongside Germany and France and aimed at forcing Japan to return the Liaodong Peninsula to China, massively inflamed nationalist sentiment in Japan as well as anger at the Russians (who promptly seized the peninsula for themselves, high minded notions of “stabilizing China” notwithstanding). In particular, Russian military leaders seized the excuse provided by the Boxer Rebellion in China (suppressed by an alliance of nations including both Japan and Russia) to move large numbers of forces into Manchuria in order to “support the invasion”, forces which were still “in the process of withdrawing” five years after the rebellion ended. When the Chinese throne demanded the return of occupied territory in Manchuria in 1903, the Russian response was to issue an ultimatum essentially demanding complete control over the administration and economy of the region before its troops would leave.

This crisis was viewed with some consternation in Tokyo, particularly because the Russians reinforced their position by moving troops close to the northern border of Korea–now a Japanese protectorate and considered by military leaders to be vital to the security of the empire. Some leaders, like Ito Hirobumi, counseled caution; however, others, like the military patron Yamagata Aritomo, took a far harder line–and were bolstered when news arrived in the early summer of 1903 that Russian forces had occupied part of the Yalu River estuary that was technically on the Korean side of the border and begun constructing fortifications.

Russia’s actions were clearly aimed at the intimidation of Japan, and likely at the longer term seizure of Korea. Japanese forces, by the estimates of its military leaders, did have a numerical edge on their Russian counterparts both on land and at sea–but it wouldn’t last for more than a few years, as Russia continued to fortify the area and move troops into it.

In these circumstances, the calls for war on the Japanese side grew more and more fervent–particularly after 1902, when Japan penned its first overseas alliance with Great Britain. That alliance wouldn’t bring the UK into a war automatically, but it would prevent other countries from intervening in a war with Russia, since by the terms of the alliance the UK would then enter the conflict on Japan’s side.

In other words, the alliance ensured that a fight with Russia would be 1:1, and that the czar could not bring in other allies as he had with the Triple Interventon, because he would then have to face down the world’s foremost power.

By late 1903, a tenuous consensus had emerged in Tokyo that negotiations to get the Russians to pull some forces out of Asia should be attempted (since that would make Korea far more secure), but if this failed then the answer had to be war. The Russian response to Japanese proposals was largely to ignore them, and so on February 3, 1904, a war council in the presence of the emperor decided to strike. On February 5, forces were secretly mobilized, and on the 8th the first shots were fired.

Japan’s strategy for the war was comparatively simple. To begin with, Russia’s Far Eastern Fleet, based in the warm water port of Port Arthur in Manchuria (today the city of Dalian) had to be neutralized. To pull this off, the Imperial Japanese Navy would rely on a bit of subterfuge–a timed strike that lined up just with the delivery of a declaration of war to St. Petersburg, so that Japan did not violate the laws of war with a surprise attack but also left the forces in Port Arthur unprepared. This worked fairly well (and became the blueprint for another such attempt in 1941), pinning the Russian Far Eastern fleet in place and sinking two of its battleships with no losses on the Japanese side. The seas thus secured, massive numbers of Japanese troops could be ferried to the mainland without fear of transports being sunk. Their goal would be to advance rapidly into Manchuria and defeat the Russian forces decisively–thus, the czar would be forced to accept defeat and make peace before the full brunt of the Russian military could be slowly shipped east to be brought down on Japan.

Here, the plan ran into problems very rapidly. Japanese tactics called on the forces of the Imperial Army to advance rapidly, seizing the offensive and attempting to encircle the main Russian army to crush it decisively. However, the Russian commanders on the scene were also aware of the strategic situation, and crucially aware that all they had to do was play for time. In the area of the Far East, Japan had a numerical advantage. However, the sheer size of the Russian Empire meant that over time, as more and more forces could be shipped east via the Trans-Siberian Railroad back to densely populated European Russia, the balance would tip. All Russian commanders had to do was play for time, retreat if threatened, and above all not lose decisively–and this is exactly what they did.

The land battles of the Russo-Japanese War read like an exercise in futility. In a series of clashes at the Yalu River, Nanshan, Motien, and elsewhere, Japanese forces advanced, took the offensive, and defeated the Russians, driving them from their positions. However, in each battle the Russian forces were still able to retreat without being encircled, and Japanese tactics–which relied on infantry charges against fortified positions where the bayonet and raw fighting spirit would carry the day–were incredibly bloody. Japan saw six times as many combat deaths in the first land battle of the war at the Yalu River as it had suffered in the entirety of the Sino-Japanese War ten years earlier. Even the biggest Japanese victory of the war, at Mukden, still saw massive losses on the Japanese side and about 70% of Russian forces able to withdraw in good order.

Meanwhile, a second land objective–seizing Port Arthur in a land attack, and forcing the Russian Far Eastern fleet out to sea to be crushed decisively by the imperial navy–proved hard going in the extreme. The commander in charge of the Port Arthur siege, General Nogi Maresuke, was a samurai of the old school without much military training, and supposeldy could not even read a terrain map–thus he ordered his men constantly to charge uphill into fortified positions, essentially giving them suicidal commands. It was only when he was quietly relieved of office, and command handed over to his second Kodama Gentaro (who correctly identified elevated terrain the Japanese could seize and use to clear the remaining Russian defenses) that victory came.

Ultimately, two factors won the war for Japan. First was the Russian Revolution of 1905, which revealed the weakness of czarist rule in Russia itself–the revolution was not a direct result of the war, since Russia had many other issues in the early 20th century from ethnic strife to corruption, but the heavy costs of a war the government had promised would be quick did contribute. A few months later, the humiliating defeat of the Russian Baltic Squadron, which had slowly made its way around the world to reinforce the fleet in Asia only to be ambushed and crushed by the Japanese at the Battle of Tsushima, secured Japan’s domination of the seas. Ultimately, czar Nicholas II decided that the time had come to negotiate rather than continue a war that was unpopular at home, over remote territories of the empire.

The final settlement, when it came (negotiated by the American president Theodore Roosevelt as a neutral intermediary) made it clear Japan had won–but not as decisively as it had 10 years earlier against China. Japan was given Russian possessions in Manchuria as well as ownership of a lease Russia had signed of Port Arthur itself, amounting to a strong sphere of influence in the region. It also received the southern half of Sakhalin island–but no indemnity to help cover the costs of the expensive war, news which caused riots in Tokyo when the populace found out they would have to see their taxes go up to cover war debts. Still, Japan had won–the first Asian power to defeat a European one in centuries. And in doing so, it had decisively secured itself a seat among the great powers.

However, like the Sino-Japanese War, the Russo-Japanese War was a poison pill of a sort. Having expanded their empire into Manchuria, Japanese military planners now began to push for even more resources to defend it–and to expand new buffer zones to protect Manchuria, itself a buffer zone to protect Korea. Justifications like this led to an expensive 4 year long intervention in the Russian Civil War that saw Japan waste huge quantities of men and materiel in a doomed effort to prop up the White Russians. The war also provided several “lessons” to the imperial military with negative long-term consequences, from the success of the Port Arthur sneak attack informing plans for Pearl Harbor to a renewed confidence in the superiority of Japanese “fighting spirit” and subsequent disregard for tactical and technological improvements to Japanese land forces in favor of emphasizing the infantry charge.

All of these “lessons” would come back to bite a military leadership that viewed the Russo-Japanese War as its greatest triumph as they attempted to replicate the same techniques against the United States in World War II–not realizing that victory over Russia had far more to do with the domestic conditions of the czarist government than Japan’s strategies, and that the US was a very different beast.

Still, riots notwithstanding, Japan was pretty unambiguously one of the great powers of the world by 1905, with a burgeoning colonial empire in Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria.

And that status would only improve as time went on; in the fall of 1914, the Tokyo government seized on the opportunity presented by a British request under the terms of the Anglo-Japanese alliance to enter World War I. Why would they want to do that? Well, because Germany had some holdings in Asia–most notably a small enclave in Qingdao on China’s Shandong Peninsula and down in Micronesia. And more importantly, those possessions were extremely lightly defended–after all, the war was mostly happening in Europe.

The Imperial Japanese Army and Navy were able to quickly sweep in and seize both territories before the end of the year with minimal casualties–and over the next few years, the Japanese government successfully pressured the other Allies to let Japan keep its new territories. In the meanwhile, Japan itself became one of the major suppliers of the war effort; alongside the United States, Japan did extremely well selling the Allies ammunition, medicine, cloth for bandages and uniforms, and pretty much everything else needed to keep the war effort going.

In the final peace deal in 1919 at Versailles, Japan was even granted a seat as one of the Great Powers deciding the final outcome of the peace–the only non-Western country at the table.

Thus, in many ways, by 1919 the dream of Meiji had been achieved–Japan was a great power, ranked among the other empires of the West as one of their peers, and having secured a colonial empire worthy of its new status.

Of course, noticeably not consulted in any of this were the actual residents of the places Japan had colonized–and it’s their story I want to end with.

And to be up front about two things: first, I am not going to try and be comprehensive in telling the story of colonization in Korea, Taiwan, or anywhere else. That’d be a whole separate series with dozens of episodes–and to be honest I’d feel a bit awkward even trying, because after all I simply don’t know Korean or Taiwanese or Micronesian history as well as I know Japan’s, and thus don’t feel as academically qualified to tackle something that is as much (or more) the story of those places as Japan’s.

Second: I am not going to go super in depth on some of the most horrific aspects of the colonial legacy, like Unit 731, the so-called “Comfort Women”, or anything else in this or future episodes. That’s because a) I have done full episodes on those things in the past, and they are in the archive if you are curious and b) I want this specific series to be accessible to anyone, which feels at cross purposes with an in-depth discussion of horrific violence and mutilation.

But I want to be very clear that those things did happen–it’s very well documented–and that they are horrific and morally unconscionable.

With that said: colonial policy towards colonized locals was broadly defined by two things: inconsistency and exploitation.

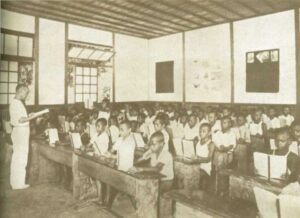

The inconsistency mostly came in the form of the perceived “end goal” of colonization. Bureaucrats in Tokyo could never really settle between two extreme positions–on the one hand, some advocated for what they called “Kouminka”, literally “Subjectification”: in other words, making Koreans or Taiwanese or what have you into Japanese subjects through assimilation. On the other hand were those who maintained a more racialized view of colonization and considered non-Japanese immutably separate from the natives of Japan.

Thus, for example, the Ryukyuan natives of Okinawa were subject to policies intended to forcibly assimilate them–banning the Ryukyuan language from all official spaces (including the school system) and converting sacred spaces associated with Ryukyuan folk religion into Shinto shrines.

However, the Ainu aboriginals of Hokkaido were subject to the 1899 kyuudojin hogohou, or “Former Aboriginals Protection Act”, which pushed the Ainu into distinctly non-assimilationist communities modeled on the reservation system imposed on Native Americans in the United States–based in the most out of the way parts of the island.

That law, by the way, was not repealed until 1997, when it was replaced by laws promoting the preservation of Ainu culture.

Meanwhile, Ainu kotan were removed to make room for “modern” settlements for Japanese settlers, governed from a centerpiece showcase city–Sapporo–that was intended to be a showcase of Japanese modernity, complete with a street grid and Western inspired architecture and lots of parks (this being the age where progressive reformers in the West were first pushing the idea of parks as a way of improving urban living).

These regions were governed by civilian governors–but in Korea and Taiwan, the military controlled the colonial system. Not that it made for more consistent policy; depending on who you got as a governor general you could see vastly different policies. For example, early in Japan’s occupation of Taiwan the government general imposed rules intended to defend traditional Confucian education–a method of winning over the locals by endorsing their customs.

In Korea, meanwhile, the confusion was turned up to 11–because some imperial propaganda emphasized the idea that Korean and Japanese cultures were fundamentally related because of their shared ancient history.

This is something that, interestingly, does not appear much at all in right-wing nationalist discourse after WWII, but which used to be a real feature of it: the idea that Japan’s ancient ties to Korea meant that in fact the two countries shared a culture, which also provided a “justification” (at least in their eyes) for colonizing Korea in order to reunite the two.

Yet even here, Koreans were never really treated as equals–instead, this rhetoric of reunification was used to justify a brutal campaign of forced assimilation which slowly saw the Korean language being forced out of schools, newspapers, and other public spaces, while Korean names were replaced with Japanese ones. Those who dissented from this forced assimilation–as a generation of brave Koreans did in 1919–were subject to harsh crackdowns.

In that year, public discourse was dominated by the liberal rhetoric of the victorious WWI Allies, and especially the American President Woodrow Wilson, whose postwar vision promised self-determination for all peoples (in other words, self-rule for those who wanted it). That promise, of course, was at best only dubiously applied to Europe and not really at all outside of it–but the rhetoric was inspiring, and in March, 1919, Korean students and activists protested for that self-determination. A group of them even penned a declaration of independence from Japan.

The reprisals came shortly thereafter. Official Japanese figures say just shy of 50,000 people were arrested for involvement in the protests. At least 700 of these were killed, but the real number is likely quite a bit higher (1100 is the most common estimate, and some scholars have suggested that’s an undercount by several thousand).

Thousands of Koreans were called upon to demonstrate “loyalty” to Japan during the wars of the 30s and 40s, with men being conscripted into the army (the navy would never take them out of fear of sabotage of its expensive ships). Women, meanwhile, were impressed into a program of sexual slavery at the behest of the military euphemistically referred to as the “comfort women program.” The horrors of this latter program in particular are the source of much ongoing tension between Japan’s modern government and the people and government of South Korea.

In Micronesia, meanwhile, the locals were treated as fundamentally uncivilized–separate even from East Asians because of their culture and language, and not even allowed access to the same levels of education (for example, anything beyond basic literacy was uncommon). Most were trained to be laborers in Japanese mines or plantations, living in fear of having their homes expropriated so that they could be converted into more “useful” roles (such as yet more plantations or homes for Japanese overseers).

I’ve done longer series on Japan’s relationship with each of these places: the eight part series on Japan-Korea relations starts with Episode 155, the Taiwan series (4 parts) with episode 252, and the one on Micronesia (4 parts) with episode 472.

I’ve also done ones on Japan’s relationship with the Ryukyus (two parts, episodes 33-34) and on the colonization of Hokkaido (5 parts, starting with episode 371).

If you’re interested in any of these subjects, I recommend going back through the archives using the various tags to see what there is. There’s a LOT more than we could possibly cover in a series like this.

I hope this all gives you some sense of the main takeaway I’d like you to have of any discussion of Japan’s empire, however. Today, you get right-wing revisionists in Japan defending the empire by suggesting that a) it was for the benefit of the locals and b) because Japan is also an Asian nation, its colonial empire was somehow fundamentally different from, say, the British.

The historical record does not back up either of these highly revisionist claims–and that’s something I want to be very clear about. Japan’s empire was deeply self-serving, and any honest analysis of the period and its legacy has to start from that premise.