This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: the economics of Meiji Japan, and a brief foray into social attitudes towards Westernization. How did Japan transform itself from being largely cut off from the world economy to central to it within half a century, and what impact did all this change have on the national self-image and culture?

Sources

Crawcour, E. Sydney, “Economic change in the nineteenth century”, Sukehiro Hirakawa, “Japan’s Turn to the West,” and Gilbert Rozman, “Social Change”, in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol V: The Nineteenth Century

Pyle, Kenneth. The New Generation in Meiji Japan: Problems of Cultural Identity, 1885-1895

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan

Images

Transcript

Last week, we talked about the politics of Meiji Japan; today, we’re talking social and economic changes during the beginning of Japan’s modernization.

And we’re going to start with the economy, because in a sense that’s the most important change that happens during this period. After all, money makes the world go round.

But the thing is that the biggest shift of the period–the beginning of Japan’s industrialization–actually took a good long while to get going, and didn’t really begin in earnest until decades into the Meiji period.

Why? Well, there are a few reasons. To begin with, much of the early 1870s was consumed with the administrative changes that needed to happen first–the abolition of the old feudal domains and their integration into the new prefecture system, the conversion of the economy from the old decentralized currencies to modern yen complete with a modern central bank, as well as the abolition of the samurai class and the thorny issue of dealing with the debts of both the old regime and the new government itself (which had taken out substantial loans to pay for the Boshin War).

Those are all substantial issues on their own–I was never really a math person, and every time I look at the currency conversion scales I get one hell of a headache–but they’re not even the biggest one.

Probably the single greatest challenge early on was the remaking of the taxation system from the old system, which took a fixed amount of the annual harvest, to the payment of taxes in cash based on assessed value. Which doesn’t sound like a huge shift, but just figuring out the new tax assessments was a huge administrative burden. Beyond that, changing how those values were assessed was, to put it mildly, not super popular out in the countryside–tax resistance was a major issue in the 1870s and 1880s, just when the government could figuratively and literally afford it the least.

That resistance often got tied up in the popular movement for people’s rights led by the Jiyuto and Kaishinto which we talked about last time.

Still, those movements were eventually crushed; the thing about the government is that it controls the army and the police, and that’s a pretty big advantage relative to a bunch of angry farmers.

But even that wasn’t the end of things. the perceived (and expensive) necessity of building modern infrastructure like railroads, telegraphs, and Japanese-controlled steamship lines, led the government to take on substantial debt by 1880–and, because it had printed a great deal of paper money to help cover costs, inflation was a major issue to the point that the real tax income of the country had only about half the value it was supposed to hold on paper.

A series of financial retrenchments by Finance Minister Matsukata Masayoshi did help deal with the issue, but only at a cost of harsh deflationary measures that created serious economic hardship–especially for small business owners running on tighter margins and in the countryside, where increased taxes forced many to sell their land to powerful landlords, or even to join the Japanese diaspora overseas and seek economic opportunity in places like Hawaii or California.

Even with all these issues, industrialization did begin somewhat in earnest as far back as 1871, but even then the results were somewhat fitful and are at any rate somewhat difficult to track because statistics before 1890 are either unavailable or highly unreliable.

What is clear, however, is that even in its difficult financial straits the Meiji state did prioritize what it saw as strategically valuable sectors, chiefly munitions and textiles.

The rationale behind the first is, likely, fairly obvious. After all, military power had helped force Japan open in the first place, and would be crucial to defending the islands in the future.

Textiles, on its face, are less so; however, demand for cloth was a serious economic issue. The influx of foreign goods after the opening of the ports had led to a massive trade deficit between Japan and the West, with textiles–produced overseas at cheap industrial prices and then undercutting domestic Japanese goods on cost and quality–leading the charge. Thus, the government in Tokyo began building plans for what is called import replacement: creating a domestic textile industry that could compete with the foreign one.

The results were mixed at best. It’s clear that these industries were heavily subsidized, to the tune of 36.4 million yen from 1868-1881 at a time when the nation was badly in debt. It is not even clear in turn whether any of these industries actually turned a profit, or whether they accomplished a secondary goal of building up a workforce familiar with industrial production methods. As a part of Matsukata’s financial reforms in the 1880s, most nonmilitary industries were privatized to help revive the national finances–these were bought up by powerful merchant conglomerates that became the foundation of the zaibatsu economic cliques. Those cliques in turn would dominate the Japanese economy until 1945, and arguably continue to do so in somewhat retrenched form as keiretsu after anti-monopoly laws passed during the American occupation after WWII.

Matsukata’s reforms cleared the board, so to speak, for continued industrialization and economic growth which would continue largely unabated until the end of World War I–and which would see the GDP grow by an estimated 300% over that time period. The main drivers of economic growth were not what we call heavy industry, however: steel, oil and gas, shipbuilding, and the like. These remained a comparatively small proportion of the economy, though in terms of year-over-year growth they did expand very rapidly.

Instead, consumer goods–chiefly food and textiles–really drove economic growth.

Food was a growing market thanks primarily to a growing population; the advent of industrial agriculture and the arrival of Western medicine saw a dramatic increase in population, from an estimated 32 million in 1872 to 44 million by the turn of the 20th century, and around 55 million by the end of World War I in the final months of 1918.

Textiles in particular would become the underpinning of the Japanese economy, as the process of import substitution did eventually begin to work and Japanese cloth replaced foreign imports on the domestic market.

Before long, Japan was even exporting cloth overseas, entering onto the world marketplace in earnest, and textiles became a major building block of industrial economy–particularly because an expanding population in the islands led to both increased demand and a growing supply of labor.

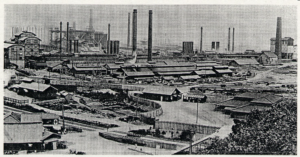

The industrial economy that developed in Japan was not, however, a free market one. Government spending in Japan was not unusually high compared to other contemporary countries, but government backed loans were a major driver of industrialization. Particularly in sectors deemed important to national infrastructure like railroads or banking, or strategic sectors related to defense, government funding was the primary driver of growth. For example, the nation’s first steelworks at Yawata was not set up until 1901, and only because the Diet, or national parliament, was convinced to financially support the industry for defense reasons–previous attempts to get them to do so had been shot down in debates on the parliamentary floor.

In turn, government planning bureaucrats expected a great deal of consideration of national objectives on the part of targeted domestic industries–Japanese capitalists were not, as one researcher put it, expected to be any less profit-motivated than their foreign counterparts, but they were expected to recognize the extent to which their profits depended on continued goodwill from the state.

That basic relationship–big businesses getting “consideration” from the state, but only insofar as they toed the lines on the goals of the state–would remain more or less intact until just a few decades ago. Down to the 1980s it was not unusual for firms deemed by the economic bureaucracy to be in strategic sectors to operate at a subsidized loss if doing so was deemed to advance economic or political objectives in other fields.

Across that whole period, ‘strategic’ was always defined in relation to overseas trade–Japan is not a particularly resource-rich nation by any stretch of the imagination, and so as the country became increasingly integrated into the global economy, finding ways to get access to the resources and money needed to realize the vision of “modernization” (whatever that meant) was a priority.

And at this point, securing resources meant one of two things–trade, or colonial expansion. We’ll talk more about Japan’s process of empire building in a future episode, though; for now, I want to focus us on trade.

And trade was a fairly complicated thing in the Meiji period, thanks primarily to the unequal treaties. Two of the core features of the unequal treaties foisted upon Japan at gunpoint by Western powers made the problem particularly immediate. The first of these were tariff limitations, which were on their face intended to enforce free trade between Japan and foreign powers by preventing either side from imposing tariffs that would make imports more expensive. According to the dominant notions of economic liberalism of the age, this would be beneficial for all involved by enabling the creation of a more efficient global market that could serve the needs of everyone. In practice, however, Japanese domestic industries–based on traditional handicrafts–often could not compete with industrially produced Western exports on price and quality.

Second were the most-favored-nation clauses that unequal treaties included. We’ve discussed these before, but as a quick reminder; Each unequal treaty had a clause granting the Western country most-favored-nation status, which meant that any future deals Japan negotiated with other powers would retroactively apply to them as well. For example, if a US-Japan deal capped tariffs at 5% between the two sides, and then the UK negotiated a deal capping its tariffs at Japan at 4%, that new 4% value would also apply to the United States as a “most-favored nation.”

However, even with these disadvantages–and with a massive revision and reminting of the currency intended to make Japan’s coinage denominations more compatible with the silver Mexican dollars used as the basis of much international trade–trade generally went well for Japan in the final years of the shogunate. In 1860, the first full year of open trade, the country exported 4.7 million mexican dollars of goods andi imported 1.7 million. However, before long the system began to teeter against Japan; in 1867, the proportion of exports to imports was 12.1 million to 21.7 million, a substantial reversal of the trade balance. To make matters worse, certain industries were particularly badly hit; there was massive demand for Japanese silk overseas, for example, which was great if you owned a silk plantation where the raw stuff was made as prices doubled or more in the span of a few years. But if you worked in a secondary field–like, say, weaving raw silk into clothing–life became very bad. By the mid-1860s about 50% of raw silk was being exported, leading to mass unemployment in cities like Kyoto where weaving was a big part of the local economy. Things got bad enough that the city magistrate began planning for riots among the unemployed and started to set up soup kitchens to head things off.

Similarly, changes to the coinage system created substantial inflation, benefitting merchants who could charge higher prices (and who were more likely to hold assets in gold, which did pretty well out of the turbulent economic times) and badly harming day laborers, samurai, and others who depended on stipends. The real value of wages for a day laborer in Osaka, for example, just about halved over the course of the 1860s.

The friction this created was actually a major factor in the downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate; the feudal domains were badly hit by these price collapses, and blamed the shogunate with its legal monopoly on overseas trade for not doing more to protect them.

After 1868, a difficult trade situation got substantially worse. The bad financial straits of the new government–which was administratively weak at first and had taken out big loans to finance the overthrow of the shogunate–were made worse by necessary economic reforms like the creation of the yen, and by general administrative confusion. Early attempts to redress the issue, like establishing government-run corporations to manage overseas trade, failed. Why? Well, in part because of resistance from domestic businesses and in part because shockingly enough the administrators responsible for running them were samurai whose lifetime of reading Confucian philosophy and practicing fighting had not, in fact, prepared them for learning macroeconomics.

The economy could not be expected to perform well under such circumstances, and the trade deficit ballooned to a total of 77 million yen by 1880.

Once again, it was the painful fiscal retrenchments led by finance minister Matsukata Masayoshi in the 1880s which turned things around; Matsukata, a Satsuma domain samurai, had been working in the economic bureaucracy since 1870 and had acquired a good understanding of how economics actually worked. His harsh deflationary measures brought the value of the yen back under control (at the cost of substantial suffering). By the early 1890s, imports and exports were about balanced, and would largely remain so for the rest of the imperial period. In addition, the expansion of Japan’s overseas empire to Taiwan and Korea in 1895 (with Korea being annexed in 1910), and then later into the Liaodong Peninsula and Micronesia, provided Japanese businesses with “captive” markets that were technically domestic and which they could easily dominate.

By the late Meiji period, Japan was a “two directional” exporter, selling silk, tea, and other in-demand primary commodities (which don’t need any processing to be ‘used’) to the West, and finished goods to the colonies, which were often cut off from Western competition. In addition, the abrogation of the unequal treaties starting in the 1890s freed the hand of Japanese bureaucrats, who were very invested in working with growing firms to build the financial power and prestige of the state.

Up until 1945, this basic pattern remained in place. The economy was dominated by light industry–chiefly textiles–and by agricultural, fishery, and forestry exports, which were also far and away the largest segments of the economy itself. By the second half of the 1910s, this pattern began to shift somewhat, as modern industries took a majority share of industrial output for the first time. But their proportion of overall employment remained small–in the 1930s, less than 20% of Japan’s population worked in any sort of modern, industrial setting.

It wasn’t until after the Second World War that Japan’s economy truly became industrial.

Indeed, much of our image of Japan today is shaped more by what happened after 1945 than before–in many ways, Japan pre-WWII was a sort of two-tiered economy. You had sectors that were deemed worthy of strategic investment–for example, steel for the military or railroads to connect the country together (and, more ominously, move soldiers around to keep order)–and which were quite modernized and up to the standard of any country in the world.

On the flip side, if you worked in a field that was not related to the export market or to a “strategic sector”, change came a lot slower. In the countryside in particular, life remained largely unchanged during the Meiji Era–much of the countryside wasn’t even hooked up to the electrical grid after 1945.

In point of fact, out in the countryside many of the same people who held power before 1868 continued to hold it after; the Meiji government found willing allies in the small number of wealthy landlords and village headmen families, who happily pledged their loyalty to the new state in exchange for titles in the local government.

In the countryside too, the economy was distinctly two tiered. Most farmers were tenants who rented their farm plots and lived lives of scarcity–a very small number were wealthy enough to actually buy up land and rent it out to those tenants, and became enormously wealthy. That pattern too would hold until the American occupation after WWII made a concerted effort to disrupt it.

And it wasn’t just farmers who worked to keep it that way, by the by. The new imperial constitution which we discussed last week gave a great deal of political independence to the military–both branches reported only to the emperor and his advisors, not to the civilian government.

And this, in turn, gave the military a lot of political sway–and particularly in the army officer corps, the countryside was viewed as a valuable source of recruits who would be toughened up by farming life and who would view being conscripted as a welcome break from the monotony and poverty of rural life.

Of course, that very cynical concern was dressed up in talk of the countryside as a bastion of “traditional values” in a modern age that was increasingly “Westernized” and therefore decadent, but it was very much self-serving.

Speaking of decadent Western culture, let’s talk about social change during the Meiji era and the early imperial period more generally.

The national ‘narrative’, so to speak, of Japan after the Meiji Restoration is probably best encapsulated by the writings of the samurai intellectual Fukuzawa Yukichi. Fukuzawa, born in 1835 near modern Osaka, was born into a lower-ranking samurai family and excelled academically despite being largely ignored by his instructors in favor of the sons of higher ranked families.

He would eventually specialize in the study of the West, and participated in Japan’s first overseas diplomatic mission in 1860 to ratify the unequal treaty with the United States.

After the restoration, he would become a major intellectual figure, founder of the prestigious Keio University and the major daily Jiji Shimpo. And it was in the pages of Jiji Shimpo that Fukuzawa captured the attitudes of early Meiji. In one of his most famous works, An Outline of the Theory of Civilization, he wrote dismissively of Japan’s entire intellectual and cultural heritage; “Only the most ignorant thinks that Japan’s learning, arts, commerce, or industry is on a par with that of the West. Who would compare a man-drawn cart with a steam engine, or a Japanese sword with a rifle? While we are expounding on yin and yang and the Five Elements, they are discovering the sixty-element atomic chart. While we are divining lucky and unlucky days by astrology, they have charted the courses of comets and are studying the constitution of the sun and the moon….While we regard Japan as the sacrosanct islands of the gods, they have raced around the world, discovering new lands and founding new nations. Many of their political, commercial, and legal institutions are more admirable than anything we have. In all these things there is nothing about our present situation that we can be proud of before them.”

In a separate editorial, one gets a hint of the ambition this sense of inferiority unlocked in Fukuzawa. This time, he wrote of his voyages overseas, and of seeing the power of the British empire over its subject peoples. Fukuzawa’s response was a mixture of pity for the locals and envy for the British–and a burning desire, he said, to raise Japan up to the same level of power as the British, so that Westerners could be driven from Asia and Japan could rule the continent itself.

While there were committed pan-Asianists in Japan who genuinely believed in a notion of Asian brotherhood against aggression from the West, within the halls of political power the overwhelming sense was that Japan had two options: it could sit alongside Western empires as Asia was carved up between them, or it could be carved up with the other powers of Asia too. Given those choices, the leaders of Meiji Japan were nearly unanimous in their preferences. Their goal became straightforward: have Japan accepted as a “civilized” nation by the Western powers, which would provide a reason to end the unequal treaties imposed upon it in the final years of the shogunate. Japan could then be accepted as the equal of nations like France and Britain, and command the same level of respect they did.

Fukuzawa himself would articulate much the same logic in one of his most famous essays–the Datsu A ron, roughly “On the Escape from Asia”, where he accused China and Korea of being “bad neighbors” for Japan in their unwillingness to Westernize and thus dragging the reputation of the region down.

It was this desire for power and respect that led the Meiji leadership to coin the phrase fukoku kyohei–a rich nation and a strong army–as one of its guiding slogans, with a great deal of money and energy pushed into military modernization as well as economic development. Those twin obsessions, in turn, would define much of imperial Japan’s history.

The army and navy, for example, would receive a great deal of autonomy in the 1889 constitution because of fears of politically motivated tampering with their prerogatives–that autonomy, in turn, would make the two service branches nearly impossible to reign in, allowing them to dominate politics until they were dismantled in 1945 at the end of World War II.

Similarly, the goal of economic strengthening led to aggressive policies of government interference in the economy spearheaded by elite bureaucrats recruited from the top universities in the nation, and those bureaucrats would dominate economic policy in the interest of the goals of the Japanese government well into the late 20th century.

And of course, undergirding all of this was a real sense of threat from the West–the discussion around power was always framed around the fear of attack or subjugation by the West. As a popular song from 1880 put it, “In the West there is England, In the North, Russia. My countrymen, be careful! Outwardly they make treaties, But you cannot tell What is at the bottom of their hearts. There is a Law of Nations, it is true, But when the moment comes, remember, The Strong eat up the Weak.”

But all that discourse around civilization and power raised an interesting question: what did that actually look like? Another of the common phrases of the era was “Bunmei kaika”–civilization and enlightenment. But what actually were those?

Early on, as the Fukuzawa quote about scenery alone being Japan’s only point of pride might clue you in on, the common thinking was that “civilization and enlightenment” meant Westernization on the largest and fastest possible scale.

In the 1870s, everything from traditional painting to the martial arts to sumo fell into neglect–the zeitgeist of the era was for everything Western.

One of the enduring symbols of the early Meiji period, for example, was the Rokumeikan, the “Deer Cry Hall” built in 1883 in Tokyo using designs from the British architect Josiah Conder.

The point of the facility–the brainchild of then foreign minister Inoue Kaoru– was for entertaining Western diplomats and representatives during their time in Japan in a space designed to replicate the height of European fashion to the greatest extent possible. The thinking was that said diplomats would come to the Rokumeikan and be impressed by the “civilization and enlightenment” on display there (in other words, by the attempts to mimic their style as closely as possible) and thus begin to treat Japan itself as a “civilized country.”

Of course, this did not work at all–the diplomatic functions housed there would dry up in a few years, and eventually the hall itself was demolished in 1941, a symbolic repudiation of the attitude towards the West which the building had stood for in the year of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As this might imply, the attitude of “full steam ahead Westernization”, so to speak, would begin to lose currency by the later 1880s. The downfall of the Rokumeikan–which was viciously criticized by Japan’s nascent political parties as a national embarassment and a colossal waste of money–is one example of that shift.

The changing winds of culture were kicked into overdrive by Japan’s victories in its first two modern wars, against China in 1894-95, and against Russia in 1904-05. We’ll talk about both of those conflicts more next week as we get into the history of Japanese imperialism, but for now I want to note that victory over China–long the greatest power in Asia–and against Russia, an actual honest to god European power, produced an explosion of patriotic sentiment.

This upwelling of nationalist pride saw a renewed interest in traditional culture as well. Shortly after the victory over China, for example, the Meiji government would begin subsidizing the traditional arts–and it would begin working with nascent modern martial arts associations to popularize “traditional” Japanese physical education over Western imported sports like baseball.

This nationalist pushback to Westernization would remain a potent political force throughout the first half of the twentieth century–Japan’s nascent fascist movement would make great hay of the notion that Japanese culture was being swamped and subsumed by Western ideas that were antithetical to its values.

And it wasn’t just the extreme right that expressed those concerns; one of the most famous literary works of the period is Natsume Soseki’s Wagahai wa Neko Dearu, or I am a Cat, released in serial form over 1905-06. The book, as the name implies, is about a cat which belongs to a middle class family in Tokyo–the cat behaves and talks in an extremely pompous fashion as it describes the melodramatics of this family and their social circle, all of whom are extremely concerned with imitating the styles of the Western middle class without really understanding them and thus come off as quite ridiculous.

The tension around Westernization would never really go away–it would remain a powerful force throughout the 20th century, and arguably still today. The scholar Chris Goto-Jones calls it the “fundamental tension” of modern Japanese history: the changes of the Meiji Period made Japan into a respected power, but they also undermined much of the value of the islands’ traditional culture.

And all that raised the question: if Japan became “modern” and “strong” by giving up everything that made it Japan, well, what was really the point? If the goal was to save Japan from Western imperialism, well, wasn’t becoming culturally subservient to the West just losing to said imperialism with extra steps?

That question–the balance of modernity versus tradition–is one of, if not the fundamental question of modern Japanese history. And again, it’s one that I don’t think has been, or really can be resolved in any meaningful way.

And you see that very clearly in the last field I want to talk about today: religion. I mentioned last time that early on in the Meiji Period the government made an attempt to formalize Shinto as a national religion, and to suppress Buddhism–a religion that had been patronized heavily by the shogunate–as a result. This program, however, was never terribly successful, and was quietly abandoned by the mid-1870s.

For the next several decades, attempts to make Shinto a central part of national identity faltered, particularly (though not exclusively) as widespread interest in foreign ideas led to a reaction against what were seen as backward Japanese notions. It was not really until 1905, when victory against Russia in the Russo-Japanese War led to a patriotic upwelling, that a renewed push to make Shinto a central part of Japan’s national identity emerged from the government and nationalistic politicians, complete with practices intended to deify war heroes or other figures who had become a part of patriotic and nationalistic narratives.

However, these attempts to create a state religion were always incomplete at best, in no small part because the constitution set up by the imperial government included a guarantee of freedom of religion–after all, such things were a standard part of European constitutions, which were the standard against which “modernity” were judged. Thus, the constitution itself seemed to bar the establishment of a State Shinto system–government lawyers constantly, and with some success, tried to argue around this by suggesting that Shinto was not really even a religion but a cultural practice, and thus could be made compulsory in schools, for example.

This is getting a bit ahead of ourselves, but: It was really in the leadup to the Second World War, when the nascent civilian government collapsed under pressure from the military as well as antidemocratic forces in the government, that State Shinto truly began to emerge. A government increasingly desperate to mobilize its population for war in China (and then the wider Pacific) turned to Shinto as a way to push subjects to ever greater levels of support and sacrifice for the conflict.

The absolutist nature of the government came to dominate the religious sphere; shrine priests followed orders from the state, and the education system promoted the idea of the divinity of Japan’s emperor and referred to him as an arahitogami (a god in human form), and attempts to argue otherwise–for example, noting that the veneration of war dead at Yasukuni shrine completely ignored a much more longstanding tradition of private veneration of dead ancestors–were ignored or suppressed.

These attempts to regulate Shinto and turn it into a “national religion”–that was also legally not a religion, of course–were never completely successful. Larger shrines could be brought around with promises of funding, but the vast majority of Shinto shrines are smaller village ones–and getting them to toe the government line was always more of a challenge.

Similarly, attempts to “export” Shinto as a colonial religion in Taiwan, Korea, Micronesia and other Japanese colonies always fell flat.

The constitution’s legalization of religious freedom–at least, within limits not prejudicial to your duties as a subject, to use its language–meant that other religions did continue to operate during this time. Buddhism remained popular; after one and a half millenia, it was simply ingrained into Japan’s religious fabric.

Christianity experienced a brief renaissance early in the Meiji era as well, with the small surviving communities of Hidden Christians who had escaped the Tokugawa purges being joined by new converts, mostly students who studied abroad early in the Meiji period.

However, the nationalist resurgence of the late 19th century saw the number of conversions plummet; Christianity, while it was now legal, never really escaped the taint of two and a half centuries of labeling as an “evil” and subversive faith. Right up to the end of the 2nd world war, Japanese Christian communities were subject to constant scrutiny–one of the big political scandals of the Meiji Era involved Uchimura Kanzo, a Japanese Christian and teacher at one of the most prominent government-run schools in the country, who was fired after a massive uproar caused by his refusal to bow to a portrait of the Meiji Emperor for religious reasons. Uchimura was denigrated in the press as a traitor to the country.

Similarly, new syncretic religious movements began to spring up during the late 19th and early 20th centuries–far more than we have room to get into here. Some of the most famous to come into existence before WWII are Oomoto, Tenrikyo, and the Buddhist offshoot movement called Soka Gakkai–all are fusions of existing Japanese religious traditions with Western philosophy or religious practice.

All were tolerated officially, but generally subject to intense government scrutiny–and any hint of “subversion”, up to and including a suggestion that their teachings were more valuable than absolute loyalty to the state–saw a crackdown.

Next week, we’ll leave the home front behind and talk about Japan’s overseas colonial projects.