This week: the age of feudalism comes crashing down, as in the span of just two years the Tokugawa shogunate goes from victory to crushing defeat. How did the final years of Tokugawa rule play out?

Sources

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan

Jansen, Marius. Sakamoto Ryoma and the Meiji Restoration

Beasley, Craig. The Meiji Restoration

Craig, Albert M. Choshu in the Meiji Restoration.

Keene, Donald. Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World

Images

Transcript

I imagine that, if you plucked a random member of the Tokugawa bakufu out of Edo castle on the Lunar New Year of 1865, he’d probably say–well, he’d probably be pretty damn confused about what happened and also at best would not speak great English, so honestly the conversation would be a bit tense.

But, assuming none of that would be an issue, our random member of the bakufu–say Tokugawa Yoshinobu, one of the many relatives of the shogun floating around the halls of power and someone we’ll return to shortly–would probably be pretty happy.

Sure, not everything was great–the unequal treaties were still an issue, and in particular tensions were riding high about the promise to open Hyogo to foreign trade as a treaty port, which had been supposed to happen in 1863 but which had been repeatedly delayed because of objections from the imperial court about allowing a foreign presence so close to Kyoto.

So no, things were not perfect, but on balance they could bea lot worse.

Which makes it interesting that, if you did the exact same thing two years later–in the lunar new year of 1867–our bakufu official would be absolutely panicking.

Why? How did things go so wrong for the Tokugawa regime, which looked like it was finally turning things around with the dramatic downfall of loyalist opposition?

The answer begins in January of 1865, in the very same Choshu domain where we left things off last time.

For a quick reminder, Choshu was one of two domains where the loyalist movement had been able to gather substantial steam, and the only one where it had taken control of the government. That hadn’t really worked out great, however; attempts by said loyalists to implement the expulsion of foreigners from Japan in 1863 resulted in a disastrous military defeat, and attempts to launch a coup and seize control of the emperor in 1864 had ended in failure and a military defeat at the hands of forces mobilized by the shogun.

Yet loyalism in Tosa was not dead; some of its adherents had simply fled into the countryside to escape the shogunate–and the pro-Tokugawa regime installed in Choshu’s castle town of Hagi at the end of said punitive expedition.

And in the winter of 1865, a few months after the end of the expedition and the withdrawal of the shogunate forces, they returned.

These loyalists were led by men like Takasugi Shinsaku, whom we talked about at the end of last week’s episode. Takasugi was a samurai who had been an avid member of the loyalist movement (among other things, he’d helped direct some of the efforts to close the Shimonoseki Straits to foreign shipping during the start of the “foreign expulsion” of 1863).

In the aftermath, Takasugi pitched an idea to Choshu’s loyalist leadership that they ended up jumping on and which would prove pretty important going forward: something he called the Kiheitai. That term roughly translates to something like “irregulars”–the Kiheitai were intended to be a mixed militia that included both samurai and, shockingly, some non-samurai as well, trained in western-style infantry combat.

This was not the first such unit; Tosa domain in Shikoku had mobilized a similar mixed force, the Minpeitai, back in the 1850s. The core notion wasn’t new to Choshu either; Takasugi’s teacher Yoshida Shoin (who himself had been executed on orders of the bakufu during the purges of Ii Naosuke) had pushed for the adoption of western infantry techniques to strengthen the domain’s military.

This is probably a good point to remember that while imperial loyalism as an ideology was opposed to the forced opening of the country and the foreign presence in Japan, loyalists were not universally opposed to Western technological innovations, the usefulness of which was hard to deny–and at any rate, the most staunchly anti-foreign loyalists were largely dead after 1864.

And the Kiheitai, in the end, proved its worth many times over. The re-emergence of loyalists like Takasugi in January of 1865 triggered a civil war between adherents of the new, pro-Tokugawa regime that had been installed just a few months earlier and those opposed to it.

The result was a decisive victory for the anti-Tokugawa side, with Takasugi and his Kiheitai proving decisive in the fighting–particularly because Takasugi was able to make use of the financial reserves that the loyalists in Choshu still had access to in order to purchase a great many French- and German-designed rifles to expand and equip his forces.

In short order, he’d find another weapons dealer as well; as the United States wrapped up its Civil War, the US federal government was eager to offload some of its wartime surpluses of equipment and would find Choshu’s loyalists an eager buyer.

Takasugi and his political allies would, after crushing the pro-Tokugawa regime in Choshu, set about rebuilding the domain and preparing it for what was almost certainly going to come next–a military response from the shogunate.

And they would not have to wait long. Early in 1866, the Tokugawa bakufu announced a plan to once again mobilize for a punitive expedition to Choshu and return a pro-Tokugawa regime to power in the domain. That plan had been under consideration pretty much as soon as the fighting broke out in Choshu early in 1865, but the shogunate didn’t formally announce a plan to intervene at first (probably hoping that the rebels against the pro-Tokugawa government could be defeated without another expensive military campaign by the shogunate)

The shogun Tokugawa Iemochi himself took up residence in Osaka castle to direct the campaign–more of a symbolic gesture than anything else, since Iemochi was all of 20 by this point and had never actually, you know, commanded an army or anything like that previously.

But still, trotting him out was proof this was being taken seriously.

Mobilization, however, took time–until the early summer of 1866, as the various domains around Choshu were ordered to muster their forces and get ready for a four-front attack on the domain and the bakufu mustered its own forces.

That mobilization was also, frankly, kind of a trainwreck. Everything took forever to come together, first because the shogun wanted an order from the emperor approving the attack to cover his political bases (which the imperial court was reluctant to give–unity in the face of the foreign threat was the order of the day in Kyoto), then because few of the various feudal domains tapped to join the assault were enthusiastic about a war they saw (correctly) as intended only to strengthen the shogunate without benefiting themselves. The whole thing was further delayed because all THESE delays saw massive numbers of soldiers gathering in central Japan with nothing to do–the cost of feeding them sent food prices skyrocketing, causing a bunch of food riots that further delayed everything.

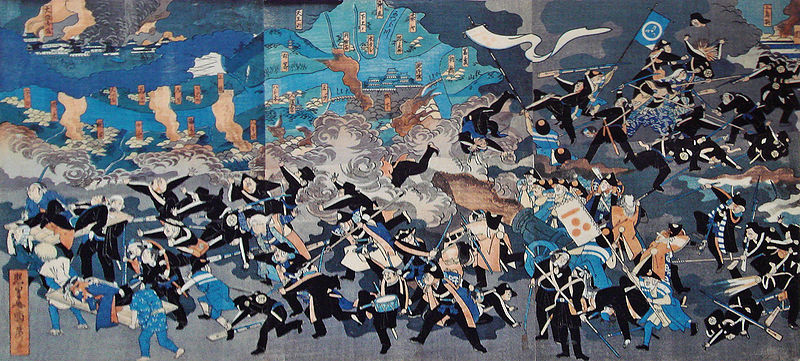

But by June of 1866, the pieces were finally in place–only for the actual campaign to be a multifront trainwreck. Seriously–the planned attacks from the east and north over land and from the west and south by sea were beaten on every single front, and resoundingly so.

How could the shogunate lose so badly? Well, the answer has been debated and studied to death, and there’s some pretty clear consensus on the major reasons. One, of course, was the logistical delays, which gave the Choshu loyalist defenders a lot of time to prepare–and dril with all their fancy new American, German, and French guns.

On the flip side, nobody in the Tokugawa shogunate had run a substantive military campaign against determined opposition in two centuries–even the previous expedition had seen Choshu fold with minimal fighting. Coordinating the attack, and doing so over both the shogunate’s own forces and all the different feudal domains involved, would be a daunting prospect for any commander.

Second, Choshu’s military forces were far more up to date than most Tokugawa planners realized–both the Kiheitai and several steamships purchased by Choshu (mostly from the UK) proved decisive in the fighting.

Third, many of the domains mobilized for the shogunate were rather halfhearted in their participation, delaying troop mobilization, sending smaller detachments than they were supposed to or in some cases refusing to participate. For some domains, it was a question of finance–war is expensive, after all. For others, it was a matter of concern over the shogunate’s long term goals. Why launch a second expedition to replace the government of a domain? Wasn’t the whole idea of the shogunate that daimyo could do what they want as long as they didn’t break any of the shogun’s rules? Choshu had before the first go-round, but what had they really done to deserve war this time?

More than a few daimyo began to wonder if this wasn’t just some prelude to a clamping down on the rights of all daimyo in the name of “national crisis”–if the shogunate wasn’t looking to centralize its power at their expense.

Most important for Choshu’s victory, however, was the revelation that one of the wealthiest domains that was supposed to support the attack–Satsuma, down in southern Kyushu–would not, and had in fact actually signed a secret alliance with Choshu.

We’ve talked about Satsuma quite a bit over the last few months (almost as if it were some kind of deliberate foreshadowing)–it was one of the outsider domains that had submitted to the shogunate after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. Its remote location far in the south of Kyushu had protected its ruling family, the Shimazu, from much retaliation for backing the wrong side–but its samurai had hung on to a resentment of Tokugawa rule.

Still, Satsuma was not a loyalist hotspot–the Shimazu family and their retainers had generally solidified around the position of kobu gattai, the unity of the shogunate and the imperial court, that had characterized more moderate policy in the 1860s.

So why side with Choshu? Well, in part out of sheer practically; Satsuma domain’s leadership, by this point increasingly dominated by an enigmatic advisor named Saigo Takamori, had become increasingly concerned that the shogunate was moving away from a moderate position–that the Second Choshu Expedition was an indicator that the shogunate was not going to compromise but in fact was looking to become even more powerful and strip wealthy domains like Satsuma of their independence.

And partially because the meeting between the two domains–which had been rivals going back to the pre-Tokugawa days–was mediated by a third party, a fascinating samurai from Tosa domain in Shikoku named Sakamoto Ryoma.

Now, there’s both a lot I could say and not much to say about Sakamoto Ryoma–on the one hand he lives very large in the memory of this period, but on the other it’s quite possible to tell the tale of the end of the shogunate without directly referencing him, because his actual role is more as a mediator and it would only be in later years that his contribution became so emphasized.

But if you engage with basically any popular media about the period you’ll probably encounter his name, so I’d feel remiss not to mention it at all.

Sakamoto had been a die-hard loyalist in his native Tosa, even going so far as to flee the domain and become a ronin in order to join the cause in Kyoto. By the time he did so, however, Matsudaira Katamori’s crackdown on the city was in full swing–so instead, Sakamoto headed to Edo, where he planned to assassinate a prominent figure in the bakufu.

That figure, Katsu Kaishu, had become prominent as an advocate for naval reform–he first entered public life as the pilot of the Kanrin-maru, the first screw-driven steam warship purchased by the shogunate, which had carried the embassy sent by the shogunate to America in 1860 to ratify the Harris Treaty.

He was also the son of Katsu Kokichi, who we talked about a few episodes back–he was the samurai who spent much of his life as a dissolute gambler and whose autobiography, translated in English as Musui’s Story, is a great look into the seedier side of Edo Period life. But that’s not too relevant for us, just fun.

Sakamoto’s plan to assassinate Katsu Kaishu went awry when Katsu, seeing the assassin coming at him, simply asked for a moment to explain himself–and Sakamoto gave it to him. Katsu Kaishu supposedly–and this story is heavily mythologized, so it’s hard to know what really happened–appealed to Sakamoto’s patriotic sensibilities, saying that he had done only what he felt he had to in order to protect the country from Western depredation, and that he too was a patriot just like Sakamoto. Theirs was not a difference of ideals but simply emphasis; Katsu was convinced the foreign threat could not be immediately defeated, and so strengthening the nation by learning from them was the order of the day.

And Sakamoto was convinced–so much so that he became Katsu’s bodyguard, protecting the man in turn from future assassination attempts.

I tell this story because it’s a wild one, and because I think it gives some insight into the mindset of Sakamoto as a figure–and why he had the clout to help broker the Satsuma-Choshu alliance.

Talks over that alliance had been going on as far back as 1865, but had broken down repeatedly given both political differences–both domains were worried about the power of the Tokugawa shogunate, but didn’t necessarily agree on strategy–and their longstanding rivalry going back to the 1500s. Sakamoto, however, was a neutral party given his background in Tosa, and his reputation as a man of honesty who was willing to hear people he disagreed with out meant that he was respected by all involved.

And so Sakamoto was able to serve as an intermediary to cut the actual alliance–which established tacit Satsuma support for Choshu (and the promise of outright military support down the line), as well as an agreement that both domains would exert themselves in the name of restoring power to the emperor.

That alliance, in turn, was incredibly important for the outcome of the Second Choshu Expedition–Choshu had been one of the neighboring domains mobilized for the first go-round, and was far and away the wealthiest military power in the area, and when its leadership declined to participate in the second round of fighting and even started sending weapons to Choshu, well, that was a big shift in the balance of power.

And as a result, the Tokugawa shogunate suffered its first military defeat since…well, honestly pretty much ever. And THAT, now that was really bad.

The German sociologist Max Weber once defined political power as, in essence, growing out of state control of violence. Or, as he put it, “A compulsory political organization with continuous operations will be called a ‘state’ [if and] insofar as its administrative staff successfully upholds a claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force in the enforcement of its order.”

I think my phrasing is a bit pithier.

What Weber is basically saying there is that political order is based on the threat of violence–that you obey traffic laws, for example, because you know if you don’t you might be fined or even arrested, and if you continue to resist you might even be subdued by force–which the people around you will accept as a legitimate result of your rulebreaking.

Choshu had broken the rules–the bakufu had tried to punish them–and instead it had gotten its butt kicked. It had proven it could no longer enforce its will via force, in an atmosphere where people were already beginning to question its legitimacy.

It shouldn’t really surprise anyone, frankly, that things went downhill from there.

After Choshu’s victory, domains around Japan began openly defying the shogunate’s rules–Western merchants in the treaty ports began to do a booming trade in weapons in particular as domain governments armed themselves for a civil war.

That was technically illegal under bakufu law–the shogunate was supposed to control foreign trade–but who was going to enforce it?

And, as a real cherry on top of this whole mess, right towards the tail end of the fighting word came that Tokugawa Iemochi, the 14th shogun, had unexpectedly died inside Osaka Castle on August 29, 1866, at the tender age of 20.

The cause of death remains contested; it’s often suggested to be beriberi, caused by the shogun’s heavily vegan diet, but we simply don’t know for sure.

And frankly, it didn’t really matter. Before his death, Iemochi had suggested a distant, three year old cousin as his heir, but literally everyone else in the bakufu rejected this notion. And so instead Iemochi’s old competitor for the job got the nod: Tokugawa Yoshinobu, who back in 1858 had been one of the two candidates for the job of shogun, but who had not been chosen because the then-tairo Ii Naosuke had thought Yoshinobu (by that point 21) would not be as pliable as the boy Iemochi.

Now Ii and Iemochi were both dead, and Yoshinobu, at 29, was the new shogun. And he did not have an enviable task before him–when word of new defeats, and even the loss of a major shogunate stronghold in Kokura in Northern Kyushu, reached him, he was forced to call an end to hostilities with Choshu.

This despite the fact that Emperor Komei, who still had not forgiven Choshu’s loyalists for trying to burn his city down, was furious and wanted to see the fighting continue.

Yoshinobu was able to convince him that the bakufu’s military position was not tenable, but this was not what you’d call an auspicious start.

Shortly thereafter, Iemochi’s death was officially announced–29 days after the shogun had passed, to give time to wind up the fighting against Choshu without demoralizing the remaining troops on the frontlines.

In fact, the shogunate technically said that the mourning period for Iemochi was why it was ending hostilities–not that this subterfuge fooled anyone.

Now, the shogunate still had one staunch supporter, and in a certain sense the one who mattered the most. Emperor Komei was a xenophobic nationalist, but also a conservative–unlike the loyalists who rebelled in his name, he did not want to get rid of the shogunate. He merely wanted its relationship to the court changed.

He remained adamant about this even after the death of Iemochi, when some of his more extreme courtiers began begging him to take power from the shogunate given the ongoing national emergency.

But Komei remained firm–accusing those who so lobbied him of treason, since they were more focused on the shogunate than the real problem of the unequal treaties.

He was staunch in this stance…until suddenly, he too got sick around the time of the new year, about one week after Tokugawa Yoshinobu officially came to Kyoto to receive the title of shogun.

The story goes that on January 16, 1867, the emperor began to feel seriously unwell during a performance of kagura dances–he’d had symptoms for a bit, but his doctors had diagnosed it as a cold. Two days later, he was bedridden, and two days after that the doctors announced he had smallpox, which he had contracted from a page named

Fujimaru who had taken ill, but recovered and returned to the palace.

He briefly recovered, but on January 30 took a serious turn for the worse and died in agony over the course of a few hours.

This is the official story, but it has been questioned for about as long as it has existed. For one thing, smallpox is extremely virulent–in the age before it was wiped out by vaccination, it would spread like wildfire and was a killer.

Which is why you should get your damn shots, by the way.

So it’s weird that ONLY Komei got sick, and from someone who had recovered from smallpox–they’re usually no longer infectious.

It’s also quite weird that smallpox has a lot of symptoms in common with arsenic poisoning, wouldn’t you know. And so the rumor has persisted down to this day that the emperor was assassinated.

Who would do this? Well, there’s plenty of theories. A courtier who hoped to get rid of the shogunate and saw Komei as an impediment, or one who saw the emperor’s antiforeignism as likely to provoke an unwinnable war would seem to be the two most likely explanations. Many names have been bandied about, but we have no proof either way–and Japan’s modern Imperial Household Agency is famously reticent to let anyone root around in an imperial tomb, so without the ability to actually test Komei’s body for arsenic residue there’s no way to be sure.

Komei’s death meant the throne passed to his only surviving child, the boy prince Mutsuhito, who at the tender age of 15 was everything his father was not–rather un-set in his ways, and pliable to the influence of his advisors.

Most people don’t know him as Mutsuhito, though–he’s better known by his regnal name, and the name he would give to the period of his reign: Meiji.

Meiji, of course, had no strong attachments to the Tokugawa shogunate. Indeed, up until this point he had not really been terribly involved in politics at all, with a traditional upbringing that focused on providing the future emperor with an education in traditional arts and Confucian philosophy.

Which wasn’t unreasonable; Emperor Komei had come to the throne young and was only 36 when he died. But it did mean that the father’s staunchly conservative worldview was not carried forward by the son.

The first year of the new emperor’s reign was one of rather tense standoffs. Though radicals at court now had a far more pliable ruler on the throne, many were hesitant to push too hard too fast–it was not yet clear whether the strength of the Tokugawa shogunate was completely exhausted.

Choshu and its newly-declared ally Satsuma, meanwhile, were busily negotiating with the shogunate, now from a position of power, as to what the new long-term arrangement of power in Japan would be given the tumultuous events of the previous year.

In the interests of time (since I am once again behind where I planned to be) I’ll spare you the back-and-forth negotiations–in the end, in November of 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu would cave in. In November, 1867 would gather the daimyo assembled in Kyoto–where he’d remained since the disastrous campaigns of the previous year–at Nijo Castle, once the bastion of Tokugawa authority in the emperor’s city.

There he would announce that he was both abdicating and returning his powers to the throne–that the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns was coming to an end.

One has to imagine this was a hard moment for him. We haven’t talked about Yoshinobu a lot up until now because of time constraints, but he’d been in the political mix for over a decade at this point. His whole adult life had been wrapped up in trying to safeguard Tokugawa rule; even after he’d been passed over as shogun he’d served in the upper levels of the bakufu leadership and had even been one of Iemochi’s trusted advisors and point-men for some delicate issues (including negotiations with the imperial court).

Yoshinobu had put SO much of his life, time, and energy into the bakufu, had been given responsibility for its future–and now presided over its end.

Now, I should note that Yoshinobu’s long term plan here remains a subject of some dispute. It was very clear that the Tokugawa shogunate no longer commanded the respect and authority it once had–its ability to martial the daimyo around Japan to fight on its behalf had clearly been hindered by the disastrous war with Choshu.

On the other hand, much of its own forces remained intact, and given the relative size of the shogunate’s own landholdings that was a substantial force in its own right–including a small modern navy and a contingent of modern-style infantry trained by officers hired from France.

Yoshinobu still had some position to bargain from, so why give up? The answer is that he really hadn’t; when he abdicated, he also circulated a proposal for what the new government of Japan could look like in the aftermath of the shogunate.

Under his proposed new regime, the emperor would be restored…as a head of state. In other words, he would play the same role that, say, the monarchy does in the United Kingdom, where the king serves as a figurehead and symbol of state authority and still has a couple of fun powers here and there but doesn’t, you know, actually run the country anymore.

Actual lawmaking authority would go to a bicameral legislature. First would come an upper house composed of daimyo, who would form an assembly broadly similar (to return to the same metaphor) to how the UK’s House of Lords used to work–daimyo would have hereditary seats to pass down to their heirs.

Second would be an elected lower house of one samurai from each feudal domain.

Together, this deliberative assembly would shape the policies that would determine the future of Japan.

But, as you might remember from your grade school civics classes, this is just one type of governmental authority–legislative power, the ability to set policy. Who would wield executive power? Who would preside over this parliament of daimyo and serve as the head of government, the actual implementer of policy? To return to the UK metaphor, who would be the Prime Minister?

Why, the daimyo with the single largest landholding would–and remember, the Tokugawa shoguns held north of 3 million koku of land, easily the single largest holding in all Japan, and Yoshinobu pointedly did NOT return his lands to the emperor in the same way he did the shogun’s own authority.

This proposal suggests that basically, Yoshinobu was hoping he could “restore the emperor” and give up the shogunate to quiet the dissenters, while at the same time securing for himself more actual power than any of his familial predecessors as the executive of a more centralized national government than Japan had ever possessed before.

Which frankly was an astonishingly clever little maneuver on his part.

Of course, it didn’t quite work out that way. Yoshinobu’s proposal would never be considered by the imperial court. For two months after Yoshinobu’s abdication, the imperial court dithered as to next steps–you see, even among the most ardent advocates of restoration nobody actually had experience governing, and nobody had really put much thought into what would come next.

Overthrowing the shogunate was all well and good, but what was going to replace it? Nobody quite knew.

In the end, an ad hoc “advisory council” to the throne, composed of politically active daimyo and members of the court nobility, took power into their own hands. And that council would, in early January of 1868, decisively turn against Yoshinobu–led by loyalists from Satsuma and Choshu, who were convinced of exactly what we just talked about: that Yoshinobu was in the midst of a gambit to “give up power” in order to secure far more of it.

On January 5, 1868, a proclamation from the emperor was issued to Yoshinobu which both accepted his abdication and declared that the now-former shogun must give up all his landholdings to the imperial court.

Yoshinobu accepted the decree, but requested some time to prepare an announcement to his followers lest they take it poorly. He then withdrew from Kyoto and Nijo Castle and relocated to Osaka, along with those pro-Tokugawa daimyo still in the city.

In a somewhat comic twist, just a few days after leaving Kyoto with the news that he was to give up all his lands, Yoshinobu received another message from the imperial court.

That message said that the first anniversary of Emperor Komei’s death was coming up, but the court had no money to pay for the observances–and asked Yoshinobu to cover the costs. Which to his credit, he did end up doing. The anniversary ceremonies went forward, just four days before Yoshinobu and the court went to war.

You see, while in Osaka castle, Yoshinobu had a change of heart. Why, precisely, is a matter of some dispute. Perhaps it had always been his plan to fight back, or perhaps hardliners in his own camp convinced him. Regardless, in mid-January he sent a letter to the court objecting to its proclamation that its powers were restored. That letter insisted that Yoshinobu had hoped to build a new regime based on peace and justice, but that the court had fallen under the influence of renegades from Choshu and Satsuma as well as extremist members of the court partial to imperial loyalism–people whom the former Emperor Komei had proclaimed disgraced.

These traitors (according to Yoshinobu) were hoping to corrupt the court with their extremism. “Even supposing these changes originate with the emperor, is it not our duty as loyal subjects to remonstrate with him? It must be said, moreover, that the signs of disorder in the country have their origins in the youth of the present emperor. This is especially the case in foreign relations: if they twist the wishes of the emperor and deal with foreign countries on the basis of temporary expedients, they will lose the trust of other countries and do great harm to the imperial land.”

Sides were being drawn for a battle, and just a few days later the final spark arrived. Word came from Edo that the outer works o the shogun’s castle had caught fire; bakufu leaders blamed Satsuma domain for this. On the same day as the fire, Satsuma samurai had attacked the fortified mansion of Shonai domain, a pro-Tokugawa fiefdom that helped police Edo. Two days after this, Satsuma’s own compound in Edo had been stormed by pro-shogunate forces, resulting in a pitched battle that burned the compound to the ground.

When news of all this made it to Osaka, the pro-Tokugawa forces in the city were furious, and Yoshinobu decided to mobile them on January 25 and march to Kyoto to “remove the evil influences” from the young Emperor Meiji.

On January 27, the two sides met at a pair of crossings just south of Kyoto at Toba and Fushimi. The shogunate forces outnumbered their opponents (mostly from Satsuma and Choshu, which had both marched troops into the city after Yoshinobu’s departure) 3:1–but in a series of attacks that lasted until January 31, it was the defenders who ultimately prevailed. And when the shogunal forces retreated, they found that several formerly friendly domains along their line of retreat were now opposed to them–a few even fired on the retreating army.

This was the end of Tokugawa rule. Shortly thereafter, Tokugawa Yoshinobu would flee Osaka by boat and give up command of his forces. Edo itself would surrender a few months later, its garrison giving up without a fight to a newly coined Imperial Japanese Army. Pro-Tokugawa domains would keep the fight going through 1868 in what is now called the Boshin War–so named from the designation of 1868 as the year of the wooden dragon, or Boshin, in the 60 year zodiac cycle.

A few final holdouts in Hokkaido would even make it a good ways into 1869.

But after this first defeat, it was clear who was going to win. The shogunate was finished. A new government was now in charge. But what was that going to look like? Nobody was quite sure–and shaking out the nature of the new Japan would prove a far more challenging subject than anyone celebrating the downfall of the shogunate really realized.

There’s a fantastic anime called Neko Neko Nihonshi which is about re-enacting Japanese history but with cats (it’s amazing, just trust me) and Sakamoto Ryouma is basically the main character. I learned about Inou Tadataka from it and have asked you to do an episode on him!

I’ve never heard of arsenic poisoning being a differential diagnosis for smallpox. I’m trying to find more about it but Google sucks now. Smallpox has some pretty notorious symptoms of being covered with pustules. There’s many famous pictures of it. I’m no doctor, but I’ve never heard of arsenic causing smallpox-like pustules. Google’s messed up their algorithm, though, so what do I know?