This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: how did the Tokugawa bakufu operate? What did the political structure of the shoguns look like? And what makes the Tokugawa era unique in the history of warrior rule in Japan?

Sources

Hall, John Whitney, “The Bakuhan System” and Osamu Wakita, “The Social and Economic Consequences of Unification” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol IV: Early Modern Japan

Jansen, Marius. The Making of Modern Japan

Philip Brown, “The Political Order” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850

Images

Transcript

When Tokugawa Ieyasu died in 1616, he left behind a new political, social, and economic order built on the lessons learned from a century and a half of civil war. And, to avoid burying the lede here, that order would prove extremely influential on Japan’s future history–the 15 shoguns of the Tokugawa bakufu, or shogunate, counting Ieyasu himself, would rule over the country for two and a half centuries and inaugurate one of the most fascinating eras in Japan’s history (at least for my money).

So it’s worth, I think, taking an episode to talk about the Tokugawa order itself and how it worked to shape so much of Japan’s future. And as a side note here, over the course of over 250 years the institutions of the shogunate obviously would evolve and change–I’m not going to get too much into that sort of institutional history, and instead going to focus on a big picture sketch.

So, with that said: obviously the apex of the Tokugawa bakufu, at least symbolically, was the shogun himself. The successive shoguns were descended from Ieyasu, and were always male–by this point, inheritance laws had come to privilege male primogeniture, and so the old medieval system where women could inherit positions and titles in some circumstances was no more.

The direct line of descent from Ieyasu would only make it as far as shogun number five (Tokugawa Tsunayoshi). Tsunayoshi, who died in 1709, did not have any surviving heirs.

However, Ieyasu and his successors had made provisions for this as well; they’d set up a series of Tokugawa relatives as so-called shimpan daimyo, feudal lords directly related to the Tokugawa house.

This entitled them to certain special privileges–for example, many of the shogun’s closest advisors were pulled from the shimpan daimyo, since they could be counted on to be loyal to the Tokugawa–and also to provide an heir to be adopted by the shogun in case one was not immediately available.

This created an interesting tension where on the one hand shimpan daimyo were considered deeply reliable given their family connections, but on the other they were always viewed with a little suspicion–after all, the shimpan were all just a few unfortunate accidents away from claiming the shogunate themselves.

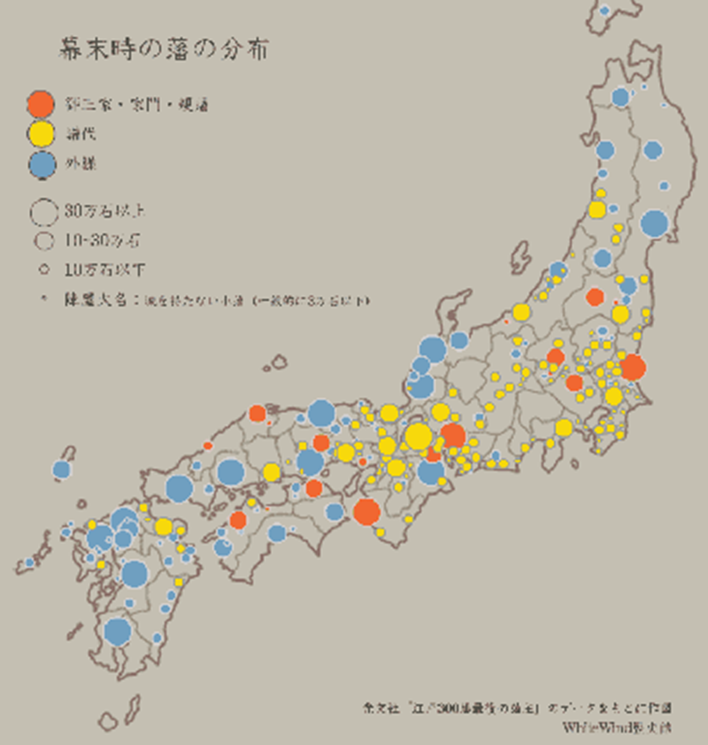

Beyond the shimpan, the shogun ruled over a host of other daimyo, feudal lords scattered throughout the country. The precise number of daimyo varied over time–over the course of the Tokugawa years there were between 260-300 different han, or feudal domains, each with their own daimyo.

There were also a host of hatamoto–direct retainers of the shogun with their own landholdings. These–and feudal lords with comparatively smaller holdings–were sometimes called shomyo, “small name”, a sort of pun on daimyo–which literally means “big name.”

These territorial lords were in turn divided into two categories, using a system that Tokugawa Ieyasu largely cribbed from the family he overthrew, the Toyotomi.

Hideyoshi, you might remember, divided his vassals into fudai–those who had been loyal to him before his ascendancy to unquestioned power–and tozama, those who had only come around afterwards.

Tokugawa Ieyasu cribbed the same system, with the dividing line landing at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. If you had pledged your subordination to Ieyasu before 1600–before he secured his decisive military advantage, in other words–you were fudai. If not, you were tozama.

The key distinction between the two was that fudai–and the shimpan relatives of the shogun–had access to positions within the bakufu, which was staffed largely by the daimyo themselves or by the shogun’s direct retainers. Tozama, meanwhile, were not allowed to hold those positions.

Ieyasu also used his decisive military advantage to reorganize landholdings, stripping territory from those he did not trust or in some cases fully relocating those families to new lands. The idea here was, of course, to reward his own followers, but also to make “untrustworthy” families reliant on him. For example, in 1615 the Chosokabe clan of Tosa domain on Shikoku joined Toyotomi Hideyori in opposing Tokugawa Ieyasu. The clan was thus wiped out, and Ieyasu decided to move a new clan into Tosa to replace them.

That clan, the Yamauchi, were tozama–their daimyo, Yamauchi Kazutoyo, had fought with Tokugawa Ieyasu at Sekigahara but as an ally opposed to Ishida Mitsunari, not as a vassal, and was thus not granted fudai status. So Kazutoyo was rewarded with a large domain, but one that was out of the way–and full of old Chosokabe retainers who resented him. That made Kazutoyo dependent on the continued good graces of the shogun to remain in power, because otherwise he risked being overthrown.

As time went on this sort of forced reorganization of land became comparatively rare–but early on in particular it was a consistent tool of the shoguns to deal with daimyo families they did not fully trust.

Within their domains, the daimyo had comparative autonomy. Indeed, this was the basic guarantee of the Tokugawa shogunate, the way it was able to compel obedience from the feudal lords. In exchange for fealty to the house of Tokugawa and an agreement to abide by the shogunate’s policy directives–about which more in a second–the daimyo were allowed functional autonomy within their territories. They could set economic policy, handle matters of crime and punishment, and do pretty much whatever else they wanted.

And as they did so, they could rest easy knowing that the shogunate would protect them–because part of the bargain of the shogunate was a guarantee that your neighbors would not attack you, and that your vassals could not depose you. In the chaos of the old civil wars, sure, you had plenty of opportunities to expand your territory and wealth, but also plenty of opportunities to lose them at the hands of an opportunistic neighbor or untrustworthy vassal. Now, the shogunate would guarantee that you and your descendants would hold your lands forever–so long as you toed the line.

Not all land was handed out in this way, of course; Ieyasu and his successors hung on to lands to the tune of 4.2 million koku, with his direct vassals holding another 2.6–about 25% of the assessed wealth of the country (Jansen p42). Those lands were often carefully chosen; Edo itself, of course, and its surroundings, were all the property of the shogun. So too were strategic cities like Kyoto (home of the emperor), Osaka (the largest trade hub) and Nagasaki (the only foreign trade port–more about that in a second). In addition, strategic resources–like the island of Sado off the Noto peninsula, home to a good chunk of the nation’s gold mines–were a part of the shogun’s tenryo.

This grand bargain was, once again, first introduced by Hideyoshi–it was how he rose so quickly in the 1580s, by offering to confirm daimyo in their holdings in exchange for obedience. Ieyasu extended and systematized this practice, which frankly was an absolutely brilliant political maneuver. After all, it gave every daimyo, be they from a big or small domain, fudai or tozama, a stake in the system–because the system guaranteed their hold on their power and privilege.

There were, of course, a few caveats–you weren’t totally independent as a daimyo, and there were a few areas where you had to toe the line. First and foremost, Ieyasu and his successors systematized rules around military readiness. For example, no domain could have more than one castle town–fortified metropolises from which to project their power.

The daimyo were also required to move their samurai into the castle towns and out of the countryside, essentially as a surveillance measure–a measure intended to make it easier to monitor them and to keep the armed warriors from causing trouble.

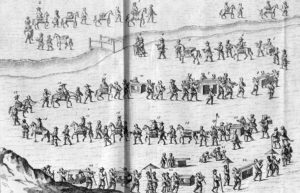

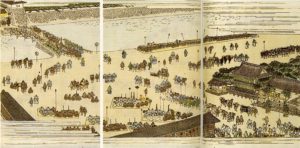

Most importantly, daimyo were all required to engage in the important but innocuously named system of sankin kotai, or alternate attendance. This system required every daimyo to spend a certain amount of time personally in Edo attending on the shogun–for most daimyo, this would be every other year (so one year in Edo, one at home).

For some in more remote or strategic feudal domains, the requirement was relaxed. For example, the So clan which ruled Tsushima between Japan and Korea or the Matsumae clan which ruled the southern tip of Hokkaido (the only part of the island under the direct control of Japan at this time) came at far less regular intervals.

While you were in Edo, you’d spend a year attending on the shogun, coming to audiences with him and just generally taking in life in the capital. Along the way, of course, you had to be maintained in style suitable to your station–daimyo were required to maintain yashiki, essentially fortified compound residences, in Edo that were commensurate with their prestige.

So, for example, wealthier daimyo had bigger yashiki, and more prestigious ones (especially among the fudai) would be granted lots to build on closer to the shogun’s castle.

They also of course had to travel to and from Edo with an entourage–commensurate in style with their rank and income, naturally.

Superficially, the goal of all this was to build bonds of personal loyalty between the shogun and daimyo–to build a personal relationship that layered on top of the institutional one created by the political structure of the shogunate.

In practice, however, sankin kotai was useful in two other ways. First, it was essentially a form of geographic wealth redistribution; the amount of money daimyo spent going to and from Edo, not to mention the entourages the daimyo themselves brought along–all people who needed to be fed, housed, and entertained for a year with their lord–brought a lot of spending money into the city, which in turn ballooned in size to accommodate this swelling demand.

Before Tokugawa Ieyasu had made it his headquarters, Edo had been a small market town without much going for it. After he was gifted eight provinces in the Kanto by Hideyoshi in 1590 and made Edo his castle town, the city ballooned to about 100,000 people. But that was just the beginning–the demands of sankin kotai, not to mention servicing the population of Tokugawa retainers living in the city itself, saw the city’s population swell. By 1650, we estimate about 450,000 people living in Edo–by 1720, around 1.2 million people.

Just for comparative purposes, at the end of the 1600s London had about 575,000 people–less than Edo, and the only urban center in England or Wales with a population north of 30,000.

By most estimates, Edo was the largest city in the world at the height of the Tokugawa period–emerging basically from nowhere in the course of about a century to rival the great urban centers of the Kansai area which had dominated Japan’s culture and economics for a millennium.

About 10% of Japan’s population lived in urban centers larger than 30,000 people, with about 30 such cities dotted across the country. Japan, simply put, was far more urbanized than Europe–the only place remotely comparable was China.

There was one other way in which sankin kotai served to benefit the Tokugawa shoguns. You see, if you were a daimyo during this period, you had to leave behind some of your retainers even when you went home–as well as your wife and children.

Ostensibly, the goal of this rule was once again the building of a personal relationship between the future rulers of the realm–but of course there was one other side to this as well. Families were intended to serve as hostages to ensure good behavior; any daimyo who contemplated rebellion had to accept that they were losing all their heirs, and thus the future of their clan, in one fell swoop if they were caught.

As you might imagine, this proved a very effective deterrent to any discussion of rebellion or insurrection.

The shogunate had other methods of policing potential dissent among the daimyo ranks, most notably its metsuke–literally “one who gazes”, essentially inspectors empowered by the bakufu to ensure its policies were being followed–but the system we’ve just outlined honestly worked pretty well on its own. THe daimyo were kept quiet–for two and a half centuries, there was no real hint of dissent or rebellion.

Now, before we leave the shogunate behind to talk about other aspects of the period, there’s one more thing to cover. I did say that there were a few areas where daimyo independence was limited and they were required to toe the line; what were they?

Well, there was quite a substantial list of rules for the daimyo, compiled in a text known as the buke shohatto, or laws for the military houses, first issued in 1615 and then re-issued with revisions a few more times over the course of Tokugawa rule.

We’re not going to go through everything in there because it would take a while, but most of the regulations concern maintaining stability in your domain (for example, by not allowing people from neighboring domains to just wander in–a measure intended to make it impossible to dodge taxes by leaving your domain of residence).

Outside of the buke shohatto, however, there are two big policies to highlight: the ban on Christianity, and the closed country edict.

To start with Christianity; you might recall that by the end of the civil wars Christianity had thousands of adherents in Japan thanks to half a century of Jesuit missionizing enabled by the desire for trade with Portugal (which could serve as an intermediary with China, since China had officially banned Japanese ships from its harbors).

Even a few daimyo had been brought round to the new religion.

However, both Hideyoshi and particularly Tokugawa Ieyasu became increasingly suspicious of the motives of Christian adherents in Japan. Hideyoshi was concerned regarding the Jesuit tendency to direct their followers towards attacks on Buddhist religious institutions, not to mention Jesuit involvement in the Portuguese slave trade–which did take enslaved Japanese war captives all over the Portuguese empire.

Ieyasu, meanwhile, shared those concerns as well as an increasing worry that Christian adherents could serve to undermine his new political order, either as overt fifth columnists supporting a Portuguese or Spanish takeover of Japan (because he was aware of how the church had supported European empires in the Americas) or simply because the religion divided loyalties that should belong (to Ieyasu’s mind) to him and his political order.

And so Ieyasu ordered the expulsion of all priests and the banning of the Christian faith in 1614. Actually suppressing the religion would take decades of brutal repression, particularly in the city of Nagasaki in Kyushu which had been a city held directly by the Jesuit order and which was full of believers.

However, it was eventually accomplished, with Japanese Christians either killed, forced to recant, or forced underground into hidden communities reliant on subterfuge to survive.

These hidden Christian communities survived primarily in the more rural or isolated parts of Kyushu, usually by disguising their worship using Japanese iconography–for example, creating images of the Virgin Mary that resembled Kannon/Avalokiteshvara, the Buddhist boddhisattva of mercy.

There’s obviously a lot more that could be said about the rise and fall of Christianity in Japan–see episode 422 for the start of a MUCH more in-depth look at the subject–but the upshot was a 250 year-long ban on the “evil religion”, enforced by both Ieyasu and all his subsequent successors. Daimyo who had converted were forced to either abdicate or apostatize, and going forward a careful repertoire of techniques were developed to catch hidden Christians. The most infamous, of course, was the so-called fumie, a practice of requiring suspected Christians to stomp on a Catholic icon–the idea being that no Christian in good standing would be willing to so disrespect their God.

One final burst of resistance in 1638–an uprising at Shimabara in Kyushu by hidden Christians–wracked the country, but the rebels did not make it far at all before being suppressed by force.

The other side of this was the so-called closed-country, or sakoku policy. Ieyasu’s overriding concern in assembling the Tokugawa order was stability–a stability intended to maintain the balance of power that placed him and his successors on top.

At first, this did not mean cutting the country off from foreign trade altogether; instead, Ieyasu continued a policy cribbed from who else but Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who began the process of officially licensing ships for overseas trade–in exchange, of course, for a cut of the profits.

These so-called Shuinsen, or Red Seal Ships, were essentially chartered trade vessels–the shogun would hand out a certain number of permits to a given daimyo, who could then pay the cost of constructing and dispatching the trade vessel in exchange for sharing part of the overall profits with the shogun.

The hope was that this system, in conjunction with opening trade with the Protestant powers of the Netherlands and England–who had made it to East Asia by the early 1600s–would make up for the faltering trade with the Catholic powers of Europe. Spain and Portugal were, of course, a bit miffed with the whole Christian ban and persecutions, and by the 1620s trade with those powers was cutoff altogether–particularly because Catholic missionaries kept smuggling themselves into Japan on the trade ships.

By the 1630s, the red seal system was dropped as well. The rationale for this choice was largely about maintaining that careful balance of power; while the red seal system worked as a method of trade, it also bolstered the power of the daimyo that participated in it, and thus had the potential to throw off that careful balance of power.

And so, under the third shogun (Tokugawa Iemitsu) the bakufu decided to end the policy of allowing domains to send their own trade vessels–instead, all foreign trade would be routed through the port of Nagasaki, once built by the Jesuits but now a part of the personal territory of the Tokugawa shoguns.

Ostensibly, the rationale for this was the anti-Christian crackdown–the edict closing the country was a part of a larger document re-iterating the ban on the “evil religion”–but practically, it’s pretty clear the major concern was ensuring that the shogun, and the shogun alone, benefitted from overseas trade.

This new trade system was restrictive enough that the English ended up dropping out of the Japan trade altogether, instead focusing their efforts in India–leading up, of course, to the takeover of the Indian subcontinent and its incorporation into the British Empire.

The Dutch, however, stuck around, and would send trade missions to Nagasaki from their colonial bases in what’s now Malaysia for the rest of the Tokugawa Period.

They, alongside merchants from Korea and the Ryukyuan Kingdom (which we will talk more about in a future episode) as well as smugglers from China defying the official ban on trade with Japan, would be the main points of contact between Japan and the outside world for the next two and a half centuries.

Hopefully all this gives you some sense of the core structure of Tokugawa rule and the policies which maintained it. But it’s important to remember that the samurai were far from the majority of the population; even if they were now pretty unquestionably on top of the social hierarchy, it’s worth taking some time to talk about what the rest of the Tokugawa system looked like.

I’d feel a bit remiss if I didn’t spend at least a little time with another small fraction of the population, albeit an important one we’ve discussed before. The nobility of Kyoto, and of course the imperial family itself, had survived over a millenium and a half of turmoil by this point and were still around–but unlike the past Kamakura and Muromachi bakufu, under the Tokugawa bakufu there was no real sharing of power with the court or aristocracy.

The Kyoto court had been largely bankrupted by the civil wars, and as had been the case with Hideyoshi was more than happy to subordinate itself to Ieyasu in exchange for the new shogun’s financial support.

Ieyasu granted the court lands to live off of, with value equivalent to a minor daimyo–141,000 koku of rice, to be specific. This was a not insignificant sum, to be sure, but also no more than a well-to-do daimyo, or feudal lord, would possess. Wealthier daimyo, such as the Mori family of Choshu or the Shimazu family of Satsuma, possessed quite a bit more land (over 230,000 koku for the Mori, and 770,000 for the Shimazu). The Maeda family of Kaga domain had over 1 million koku of lands, and of course the shogun had his 4 million+.

Ostensibly the old civilian government still operated, appointing ministers of the left and right and provincial governors and court ranks and all that good stuff. But practically speaking, these were simply honorific titles handed out at the request of the shogunate to people it wished to recognize–being named governor of whatever province carried no actual authority, and indeed more than a few daimyo were named governors of provinces where they didn’t even hold lands just because it was a nice honorific to have on your resume, so to speak.

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu and his successors maintained the fiction that all of this was being done in the emperor’s name to “ease the imperial mind” and “remove distractions” so that the august inhabitant of the throne could instead contemplate the arts and religion and other things more worthy of his divine countenance.

Of course, that’s all fluff–the emperor was a figurehead, and after 1632 was even trapped by law within the grounds of the gosho, the imperial palace complex in Kyoto. From 1632 to 1863, barring the occasional fire or natural disaster which necessitated evacuating the palace, the emperors of Japan did not leave the palace itself.

Their power was also heavily circumscribed; for example, in past centuries the imperial court had managed much of Japan’s institutional Buddhist framework, reserving the right to confirm abbots and promote monks from major monasteries. Even that power was stripped away, and when one recalcitrant emperor attempted to hand out promotions anyway, the shogunate retaliated by stripping said monks of their honors.

The imperial throne was also brought more directly under shogunal control via a marriage arranged between the 108th emperor Go-Mizuno’o and Tokugawa Masako, grandaughter of Ieyasu by way of his heir Hidetada. Masako was chosen, of course, to be a pro-Tokugawa voice at court and to ensure that future emperors would have some Tokugawa ancestry. She was more successful at the former; she only had one child who would sit the throne, the future Empress Meisho. But she did become a powerful pro-shogunate voice at court, and as empress adopted all children her husband had and thus raised served as the parental figure for several more future emperors.

More broadly, the nobles of the Kyoto aristocracy did largely buy into the Tokugawa system. They now had stipends to support them, albeit not particularly generous ones, and could usually make some extra money by serving as cultural tutors in poetry, painting, or other artistic pursuits associated with the court nobility–and which many a daimyo was eager to learn in order to prove themselves cultured.

Many aristocratic families also farmed out their daughters, so to speak, as wives for samurai families looking for some more legitimacy or prestige to their names–a tidy arrangement for the male leaders on both sides, though one that didn’t take the feelings of those most directly involved in the deal (so to speak) into account.

But what about the rest of the population? Well, here at long last, we can finally say that there is actually a pretty good written record. Peace brought with it stability and prosperity, leading to a general boost in living standards that saw a LOT more access to literacy. Particularly successful in this regard were the so-called terakoya, or temple schools, built by Buddhist institutions around the country in order to instruct the population in Buddhist doctrine and literacy (which would enable students to then read more Buddhist texts).

Estimating literacy during this time is a challenge, but the usual number you see is around 40% of the population as a whole knowing how to read and write. Which is pretty damn impressive for a pre-universal education society.

We also know that Japan’s population absolutely boomed during this time, though by precisely how much is hard to say. The shogunate did engage in regular population censuses, but the censuses themselves were administered by the domains and then dispatched to the shogunate, where officials rewrote the numbers into province-level counts. How well this was done, and how accurate the domain-level data was, is a matter of some dispute. The shogunate’s own numbers put the population at around 26 million in 1700 (up from an estimated 18 million in 1600), though many scholars today agree this is an undercount. It’s more common to suggest a peak population for the Edo period of around 30 million people.

By comparison, in 1700 France had a population of around 18 million, and the UK at the time of its formation in 1707 of around 5.5 million.

Unlike France and the UK, however, population growth in Japan leveled off around 1700. Why, precisely, is a matter of some historical debate. Likely rising standards of living contributed to an extent–it’s well documented that an increase in living standards leads to a decrease in fertility rates, as well as access to family planning.

Regardless, the total population would level off starting around 1700 and would remain consistent until the abolition of feudalism and the beginning of industrialization a century and a half later.

Now, what I find truly fascinating about the lives of non-samurai during this period is that they were largely self-managed. The Tokugawa system relied very heavily on what you might call devolved responsibility.

So, for example, if you lived in a farming village, the local fief holder–the daimyo, a representative of the shogun if you were on his lands, whoever–would designate one family (or a group of families) to serve as headmen. Those headmen were responsible for collecting taxes and enforcing policies, but as long as they did so they were generally left alone.

Similarly, artisans or merchants in the cities were divided into neighborhoods led by neighborhood elders with much the same role.

Which isn’t to say the relationship between the ruling samurai and the populations they controlled was free from any antagonism. In particular, there wasn’t much of a mechanism for what you might call productive feedback–any sort of collective action to, say, protest tax rates (usually the most common thing to be peeved about) was viewed as conspiracy, and the ringleaders were often executed.

To get around these restrictions, protesting commoners would often sign petitions in a circle so as to avoid putting any one name first and thus identifying a ringleader, and would march en masse to present demands rather than appointing representatives.

Disputes between samurai and commoners could get acrimonious, or even violent–suppressing protest against the existing order. For example, in 1764 about 100,000 farmers marched on Edo to to protest part of their tax burden–specifically the demand for corvee, essentially taxes paid in manual labor for projects on behalf of the shogunate.

The response of the bakufu was to deploy its samurai with weapons and order them to disperse the protests by force.

Such spectacular uprisings were a rarity–few domains had them, and given how they were handled none had more than one.

This was a system, after all, that was premised on warrior supremacy–and as long as the warriors were the ones who had weapons and the know-how to use them, that would be hard to challenge.

However–and this is an important note to end on–the system intended to keep the warriors on top was not, in fact, without its issues.

The Tokugawa system was designed for stability–maintaining the existing social, political, and economic order. But that very stability meant that when the system started to get out of whack, bringing it back into alignment was a challenge.

What do I mean by that? Well, for a start, the Tokugawa were successful in bringing peace, and with it economic growth. Trade flourished, making artisans and merchants in the cities rich; in rural areas, farmers dealt with heavy tax burdens, but also had ample opportunities for dodging taxes with hidden farm fields or side jobs in sake brewing, silk weaving, and the like thanks to samurai living in the cities and only rarely venturing out to the countryside.

As a result, growing numbers of merchants and farmers began to surpass their ostensible masters in terms of wealth–dressing more nicely and living in more luxury than the members of the warrior class.

To quote Denis Gainty in his essay on the samurai during the Tokugawa period: “The result was a sort of cultural gekokujō, in which the lower (merchants) were overtaking the higher (samurai) in the social order. The problem was widespread and significant; samurai were forced to borrow from merchants in order to keep up the required appearances of class and rank, and the Tokugawa government at several points was forced to cancel samurai debts to merchants in order to staunch the free flow of capital from the highest to the lowest social class.”

The shogunate tried various methods of dealing with this, from increased taxed burdens to sumptuary laws banning certain types of elaborate or fancy clothing.

But these were not terribly effective–and as years went on, samurai economic straits became increasingly dire. Without wars to fight, the main work open to samurai was as administrators, but there were never enough administrative jobs to go around. Otherwise, members of the warrior class were left to rely on annual stipends that did not keep pace with price increases or economic growth in general–and most estimates suggest about 25% of samurai were affected by this lack of employment.

The effect was particularly pronounced on lower-ramking members of the warrior class, as what administrative positions there were often were handed down within family lines based on prestige rather than talent.

These sort of issues were seeded into the fundamental mix of the Tokugawa order–and would eventually be part, though not all, of what brought it down. In the end, a system intended to maintain stability could not cope with the viscitudes of change.