This week on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History: Hideyoshi may have brought peace, but Tokugawa Ieyasu would be the one to make it lasting. How did Ieyasu seize power from Hideyoshi, and what did he do to secure it?

Sources

Totman, Conrad. Tokugawa Ieyasu: Shogun.

Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi

Asao, Naohiro. “The Sixteenth-century Unification” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol IV: Early Modern Japan.

Images

Transcript

We have covered a LOT of famous names so far on the Revised Introduction to Japanese History, from poets to statesmen to religious leaders and everything in between–and yet, when we think of the “great names” of Japanese history, so to speak, I think it’s fairly clear that Tokugawa Ieyasu stands above them all. He is, simply put, possibly the most famous person in Japanese history–and, while such things are hard to quantify, I think it’s clear that his impact on the course of Japan’s history was massive.

We have, of course, already covered Ieyasu’s origins–originally named Matsudaira Motoyasu, he was the heir of a minor family from Mikawa province and spent his youth as a political hostage, first to the Oda and then to their more powerful neighbors the Imagawa.

After Oda Nobunaga crushed the Imagawa once and for all at the Battle of Okehazama in 1560, he wisely hitched his wagon to Nobunaga’s rising star and eventually found himself among the inner circle of Nobunaga’s most prominent generals.

It was during that period that he changed his name as well.

After Nobunaga’s death, Ieyasu made a brief attempt to take control of the Oda clan–by which I mean of course he attempted to show his profound loyalty to his master’s memory by elevating one of his sons, Oda Nobukatsu, to leadership of the clan. In the process, he briefly came to blows with Hideyoshi, and actually is one of very few commanders to defeat the Taiko’s forces on the field of battle in 1854 at the battles of Komaki and Nagakute–but eventually Ieyasu realized he could not prevail against the sheer numbers and resources Hideyoshi could bring to bear, and abandoned his campaign in favor of accepting Hideyoshi’s preferred candidate, the infant Hidenobu.

As Hideyoshi accrued more and more power to himself, Ieyasu was once again loyal to his new master and quickly became a part of the inner circle.

Hideyoshi would reward this newfound loyalty, but would never fully trust Ieyasu. For example, two years after reunification, Hideyoshi would offer Ieyasu a deal–give up the five provinces along the Pacific Coast he’d accrued over the course of his career in exchange for eight. Which on its face is quite a bargain, but those eight provinces were further from the center of the country, in the Kanto plains that had once been home to the Kamakura bakufu–and full of samurai left over from the former rulers of the area whom Hideyoshi had deposed, and whose loyalty to a newly installed Ieyasu would be questionable at best.

Ieyasu took the bargain, and spent the next few years building a new power base for himself in the east centered on an administrative headquarters built in a sleepy fishing village called Edo.

Now, one of the great questions of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s life is the nature of his ambition. Did he always intend to seize power for himself in the long term, hoping to outlive Hideyoshi (four years his senior) and take advantage of the instability of succession to do so? Or was he a pure opportunist who saw an opening and seized it?

We don’t have anything from the man himself on the subject, of course, and so can only speculate. But I do think it’s hard to argue that some of Hideyoshi’s decisions after his success at finally reunifying Japan in 1590 left ambitious men like Ieyasu a big opening.

The issue of succession, as we talked about at the end of last week, was of course a big one. We’ve had our share of succession crises at this point in Japanese history, so the key issue here is not new to us–in a political system where loyalty to the state was also wrapped up in loyalty to (or at least fear of) an individual, the replacement of that individual with another always meant a period of some uncertainty.

And Hideyoshi, to put things lightly, did not set his heir up for success. He had difficulty conceiving (and what kids he did have tended to die in childbirth)…at least until 1592, when one of his concubines gave birth to a child–Toyotomi Hideyori.

That concubine is known as Yodo-dono, and she has a fascinating life all her own. She was the eldest of three daughters born to Oichi and Azai Nagamasa– the sister of Oda Nobunaga and one of many people who got in his way and paid the price for it.

For his defiance, Azai Nagamasa was killed (Oichi herself was spared, but remarried to one of Hideyoshi’s enemies and killed herself during his downfall). Nagamasa’s sons met a similar fate, but his three daughters were spared and took up residence with the Oda.

Yodo-dono would end up in the household of Hideyoshi. Her younger sisters would end up in similarly influential positions; the second, Ohatsu, would marry Kyogoku Takatsugu, who was a follower first of Nobunaga, then Hideyoshi, then Ieyasu–and the third, Oeyo, would end up (after a few failed marriages) with Tokugawa Hidetada, Ieyasu’s son and heir.

Anyway–the son born to Yodo-dono and Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1592 is known as Toyotomi Hideyori, and his birth pretty much upended the whole succession discussion.

Previously, Hideyoshi had favored his nephew Hidetsugu to take over for him–but after Hideyori’s death Hidetsugu would end up increasingly in disfavor and ultimately would be killed in 1595.

The traditional interpretation of his fate is that Hideyoshi wished to avoid any sort of ambiguity over who would take over–that he killed Hidetsugu to remove a potential challenge to his new heir.

The records we do have from those close to Hideyoshi–though again, none from the man himself–complicate the picture somewhat, suggesting that at first Hideyoshi decided he would divide control between his nephew and son after his death, or set Hidetsugu up as a regent (he was 24 when Hideyori was born).

However, a growing concern over a disputed succession mingled with concern over Hidetsugu’s character. Hidetsugu was apparently given to a vicious cruel streak; one account by the Jesuit Louis Frois (who presumably had no dog in the fight) describes him as practicing with a musket by having his personal guards grab a random traveler to serve as a target.

Obviously, Hideyoshi himself had no problem with cruelty, but there’s a difference between a willingness to use violence and a preference for it–and Hidetsugu may well have been on the wrong end of the scale there.

Regardless of why precisely Hideyoshi made the call, Hidetsugu’s death did create a slight issue for the Taiko. He had a son, but that son was VERY young, and by the 1590s Hideyoshi was getting up in years (55 years old when his son was born, and 55 hard and stressful years at that). If he could hang on until Hideyori was older, that’d be one thing–but in the end, he couldn’t, as Hideyoshi (spoilers) would live only six more years after having his heir.

The other issue that destabilized Toyotomi rule during the 1590s was Hideyoshi’s controversial choice to launch a full scale invasion of Korea. Now, even while unification was still going on in the 1580s, Hideyoshi himself made reference to plans for continental expansion; in a letter to his wife Nenehime in 1587, he wrote that, “by fast ships I have dispatched orders to Korea to serve the throne of japan. Should Korea fail to serve, I…will punish that country…even China will enter my grip; I will command it during my lifetime.”

He said the same to one of his own vassals in 1586, Mori Terumoto (of the same Mori clan from a few episodes back): “I will command China in my lifetime.” And in that same year, the Jesuit Louis Frois recounted a conversation with the Taiko: “he also said that he had reached the point of subjugating all Japan; whence his mind was not set upon the future acquisition of more kingdoms or more wealth in it, since he had enough, but solely upon immortalizing himself with the name and fame of his power; in order to do so he was resolved to reduce the affairs of Japan to order, and to place them on a stable basis; and this done to entrust them to his brother [Hidenaga], while he himself should pass to the conquest of Korea and China…and if he met his death in that undertaking he did not mind, inasmuch as it would be said that he was the first lord of Japan who had ventured on such an enterprise.”

Clearly Hideyoshi’s own ego was a big part of this decision–his desire to be immortalized as one of the greatest figures in Japanese history led him to attempt something no other figure in Japanese history ever had (at least, not since the age of myth; according to the Kojiki the mythic Emperor Chuai and his empress Jingu had invaded Korea back in the 200s CE, but there’s no period documentation of that).

However, was the decision for invasion just a matter of ego? There are a few other theories that tend to get bandied about to explain Hideyoshi’s decision.

The most common is that after reunification, Hideyoshi faced the same dilemma every other ruler from the warrior class we’ve discussed had–how to maintain his supremacy without the ability to secure loyalty by distributing loot from victories.

One of the main ways he’d been able to secure his power was of course by bribing his followers with land and treasure from the defeated–but now that was no longer possible.

At least, it wasn’t without starting a new war.

A related reason that’s often suggested is the need to occupy, for lack of a better word, Japan’s warriors. Hideyoshi had, over the course of his rise, built a sort of military coalition with himself on top, supported by his fudai–his trusted retainers and followers–and then the tozama, the wide range of daimyo whose loyalty to him was doubtful but who accepted the Taiko’s rule because of his substantial military power.

The problem with that balance, however, was that over time it would naturally shift–his enemies would rebuild their armies and finances over time, and who was to say the balance would not tip their way eventually?

A new war was a new project, for lack of a better word, to keep them occupied–to drain the wealth and manpower of the samurai class so that said wealth and power could not be turned against him.

Which is a pretty messed up way to think about invading another country, but there you have it.

Then of course, there’s the question of madness. One could definitely characterize Hideyoshi’s behavior in the 1590s as erratic–the Korea invasion, the sudden about-face on Hidetsugu, and a few other things besides (for example, a crackdown on Christians in 1596 and the execution of one of his most prominent advisors, the tea master Sen no Rikyu, in 1591).

And this, combined with some increasingly outlandish public statements–in a letter to the King of the Ryukyus, Hideyoshi described being blessed by Amaterasu herself during the moment of his birth–have led some to suggest that Hideyoshi’s very success had driven him over the top and led him to be consumed by his own ego and who had descended into a violent madness against any and all he saw as a threat.

And of course, this is not impossible–but it is worth noting that there are other ways to explain what might seem superficially to be a descent into madness. There are explanations for the Korean campaign beyond a descent into insanity–brutal, ruthless ones that any moral person would reject as a reason for war, but if you’re a moral person I frankly don’t think you make it to the kind of position a guy like Hideyoshi held. Similarly, there were rational, if brutal, reasons of state for killing Hidetsugu.

The Christian crackdown similarly can be explained in terms of a growing concern regarding the threat of the church to Hideyoshi’s careful balance of power–after all, the church demanded loyalty from its followers, loyalty that would naturally conflict with Hideyoshi’s desire for political power and control.

And to be entirely frank here, it wasn’t like the church was entirely innocent. Hideyoshi had issued an edict banning Catholic missionaries from Japan in 1587 but had not really enforced it–clearly an attempt in retrospect to rein in the explosive growth of the church without alienating it or Japan’s Christians completely.

He clearly wanted continued trade with the Portuguese (and later the Spanish, who found their own way into Asia), but was concerned at the possibility of the church undermining his authority or serving as a fifth column supporting Portuguese or Spanish imperial expansion in Japan.

Indeed, the inciting incident for the Christian crackdown of 1596 was a dispute over a Spanish shipwreck in the domain of one of Hideyoshi’s followers (the daimyo of Tosa, Chosokabe Motochika). While Hideyoshi’s bureaucrats were adjudicating in essence a salvage dispute over the shipwreck between the Spanish and Tosa domain, the Spanish ship captain essentially bragged about the reach and power of the Spanish empire and intimated that the Catholic Church itself was essentially a wing of the empire–its followers could be directed to turn against Japan’s government in the name of Spanish conquest.

He’d hoped to intimidate Hideyoshi. Instead, he got himself and several other Christians executed–an example of what happens when you try to scare Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Sen no Rikyu’s fate has a similar explanation; he was not just a tea master, but one of Hideyoshi’s advisors, and may have gotten caught up in a political division between rival camps of Hideyoshi’s government and been using his influence to enrich himself.

Obviously there’s more to each of these stories than we can fully get into here, but the upshot is that while it’s quite straightforward to say “Hideyoshi was a few karuta short of a full deck”, the reality is a bit more complex.

Hideyoshi, at the head of a coalition government that he had built as he had gone along and with little to legitimate his rule beyond military power and an alliance with the imperial court, may have simply gambled that relying on violence (which after all had gotten him this far) would hurt his dynastic ambitions less than being too timid.

If that was the idea, though, it did not work. Hideyoshi would take ill in 1598 and die before the end of the year at age 61. He left behind a wasteful and deeply unpopular war in Korea–which did succeed in draining the treasuries and manpower of the daimyo, but mostly those of the daimyo who most supported the Toyotomi house, and which was promptly and quietly abandoned by his successors without any real gains. He left behind an heir who was, by this point, only six. And he left behind a reputation for violence that alienated many–for example, the daimyo Mogami Yoshiaki, previously a loyal supporter of Hideyoshi, lost a daughter who was married to Toyotomi Hidetsugu when the former heir was purged and never forgave Hideyoshi for not sparing her.

So, all of that explains why the position of the Toyotomi house was weak when the Taiko died in 1598–but why was Tokugawa Ieyasu the one to seize power?

In part, the answer is that Ieyasu himself was trusted by Hideyoshi, at least to an extent. As the Taiko lay dying, he new that his six year old heir was in no position to take over for him, and thus decided to set up a council of five elders to serve as regents for him.

Ieyasu was one of those regents, alongside the daimyo Ukita Hideie, Maeda Toshiie, Mori Terumoto, and Uesugi Kagekatsu. The theory was that each of these daimyo was both loyal to Hideyoshi–or at least, had shown a willingness to go along with him from early in his rise–and distrusted the others. Thus, they could hopefully balance each other out, as if any one tried to seize power after Hideyoshi’s death the others would combine to stop him.

Together, they were to manage Hideyori’s education as the boy grew up inside the walls of Hideyoshi’s main fortress at Osaka–the port city along the inland sea at the mouth of the waterways that led to Kyoto itself, built atop the ruins of the old Ishiyama Honganji. They were also to manage the affairs of the country by consensus in Hideyoshi’s name until Hideyori reached his majority.

At least, that was the theory. In practice, things broke down fairly quickly.

The immediate inciting incident was the death in 1599 of one of the regents, Maeda Toshiie. Toshiie had been a longtime follower of Oda Nobunaga and one of the very first to jump ship to Hideyoshi–one of the lead commanders, in fact, at Hideyoshi’s glorious victory at Shizugatake which we talked about last week. As a result, he had been handsomely rewarded, and was both personally very loyal to the Toyotomi and one of the most powerful daimyo in Japan.

His heir Maeda Toshinaga was less directly loyal to the Toyotomi and friendly to Ieyasu–who was already the most influential member of the regents. The relocation to the Kanto which had been intended to both reward Ieyasu and keep the ambitious man further from Kyoto had worked out well for him–Ieyasu now commanded lands worth 2.4 million koku of rice according to the land surveys compiled by Hideyoshi, making him by far the wealthiest of the five regents. His position in the Kanto plains also enabled him to build strong relationships with many of the smaller clans of eastern Japan.

By comparison, the next wealthiest regent was Uesugi Kagekatsu with 1.2 million koku, and the poorest was Ukita Hideie with 570,000.

All of which is to say that Ieyasu’s strong starting position among the regents, combined with the “flipping”, so to speak, of the Maeda (who were the second poorest of the regents, with a measly 830,000 koku to their names) led to the careful balance Hideyoshi had attempted to craft collapsing within just over a year of his death.

Still, Ieyasu’s advantage was not decisive, chiefly because while he had a strong power base in the east, much of the West of the country was controlled by his enemies.

In addition, Uesugi Kagekatsu–again, the second wealthiest of the regents–was situated in what’s now Niigata to the north of Ieyasu’s heartland in the Kanto. Which presented a huge tactical issue, because it meant that Ieyasu had enemies both to the north and west of him, and were they to coordinate in an attack he would have to split his forces to deal with them–leaving him very vulnerable to being overwhelmed on one side or the other (or both!)

The breaking point came in the summer of 1600, beginning with news reaching Ieyasu in Osaka (where the regents met to manage the affairs of the realm) that Uesugi Kagekatsu had begun a military buildup in his territory. Ieyasu, perceiving this (not unjustifiably) as a threat to himself, sent Kagekatsu a letter declaring the buildup a violation of the laws left in place by Hideyoshi (which it was) and demanding that the regent come to Kyoto to explain himself.

Kagekatsu responded by denying the charge and accusing Ieyasu of his own violations of Hideyoshi’s decrees, for example by arranging marriages with other powerful clans without permission from the regents (since such marriages could be the basis of an alliance aimed at the seizure of power–and yes, Ieyasu did do that).

And from here, Ieyasu and Uesugi Kagekatsu both mobilized their forces and prepared for a fight. At this moment, another of Ieyasu’s enemies, a senior Toyotomi retainer named Ishida Mitsunari, decided to organize his own anti-Tokugawa army in Western Japan and begin a march east to crush Ieyasu.

The summer campaign of 1600 is probably one of the most studied campaigns in Japanese history, because the results would be decisive on the Tokugawa side. Ieyasu, at the start of the campaign, was hemmed in by enemies to the north in the Uesugi and by the advancing Western army of Ishida Mitsunari. However, he had a few cards left to play of his own.

Remember when, a few episodes back, I talked about the rise of the Date clan of northern Japan, one of the families to emerge from obscurity during the civil wars under the leadership of Date Masamune? Well, Masamune’s brash and aggressive style had led him to repeatedly defy orders from Toyotomi Hideyoshi to submit, and it was only the personal intervention of none other than Tokugawa Ieyasu that kept him in power. Masamune, as a result, was somewhat well-disposed to Ieyasu, and joined his forces when the summer campaign kicked off–and with the help of Ieyasu’s eldest son and heir Tokugawa Hidetada, he was able to keep the Uesugi from making much headway against Ieyasu’s forces.

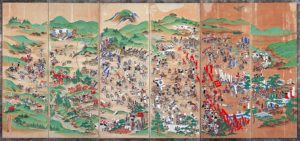

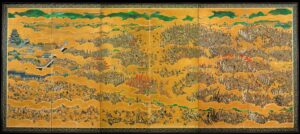

Meanwhile, Ieyasu took the bulk of his forces west to deal with Ishida Mitsunari. The two armies met on October 21 at Sekigahara in what’s now Gifu Prefecture more or less in the center of Honshu, and in the end Ieyasu prevailed.

Crucial to his victory were two defections from Ishida’s side. First, while the Mori clan of Western Japan arrayed themselves against Ieyasu, one of the close advisors to the clan leadership, Kikkawa Hiroie, decided that Ieyasu was likely to win–and so cut a separate deal with Ieyasu. On the day of the battlefield, Kikkawa, one of the vanguard commanders of the Mori contingent, delayed joining the fighting while positioning his own forces so as to block some of the rearguard elements of the Western force from coming up to join the battle.

More dramatic was the betrayal of Kobayakawa Hideaki, one of the commanders on the Western side and son of Hideyoshi’s brother in law. Perhaps because of this family relationship, Kobayakawa had been given a high-ranking position in the command of the latter part of Hideyoshi’s Korean War; by all accounts, he was not a particularly gifted commander, and in particular was routinely criticized for his handling of the war by another highly placed member of the Toyotomi leadership, Ishida Mitsunari.

As you might imagine, Kobayakawa had little love for Ishida because of this, and thus was open to being persuaded that, all things considered, he might be better off turning on Ishida and the Western army.

Come the day, Kobayakawa hesitated for a time–but ultimately after the first few hours of fighting he decided to follow through and cast his lot in with Ieyasu. Which was disastrous for the Western forces, because Kobayakawa’s forces were tasked with securing a high-ground flank for the Western army–once he betrayed them, his forces could fire down onto the Western army from the side while Ieyasu’s forces attacked from the front.

Hit from two sides, the Western army disintegrated. Ishida himself fled the field, but was captured by peasants in a nearby village and turned over to Ieyasu for a reward. Not really the sentimental type, Ieyasu had him beheaded and the severed head put on public display.

The Battle of Sekigahara was, in retrospect, the climactic moment for Tokugawa Ieyasu’s political career. He did not roundly defeat all his potential rivals–several powerful clans that aligned against him, such as the Mori of western Honshu or the Shimazu of southern Kyushu, were able to escape with their forces relatively intact. However, in the aftermath of the Western army’s defeat Ieyasu’s backers now had a clear military advantage.

He would spend the next few years solidifying his base of power by taking advantage of this new military supremacy. And it’s very important once again to note that supremacy was not complete–victory at Sekigahara did not guarantee Ieyasu complete dominion over the country.

What do I mean by that? Well, let’s look at one hypothetical example in the form of our old friends in the Mori clan. The Mori, by this time headed by Mori Terumoto (grandson of the great Mori Motonari), were quite prominent on the Western side of the conflict. The clan’s own forces were also largely intact thanks to the interference of Kikkawa Hiroie, and so Terumoto was able to make it back from Sekigahara to his castle town of Hiroshima in Western Honshu.

Ieyasu did not particularly like or trust Terumoto, but had a challenging choice to make in terms of dealing with him. He certainly had a numerical advantage that could have been pressed with an invasion of Terumoto’s territories in Western Honshu intended to remove the Mori from power once and for all.

But that would be a massive undertaking; Hideyoshi had left the Mori, who had come over to his side peacefully and early, with five whole provinces in a part of Japan that was remote from Ieyasu’s own home base. An invasion would be extremely expensive in both manpower and money, and of course, the thing about war is that there are no guarantees–something can always go wrong, and even with an advantage there’s no certainty of the outcome.

And remember, while Mori Terumoto was among the most prominent remaining anti-Tokugawa voices, he was not the only one, or even necessarily the one who would be the most difficult to deal with. There were many such clans scattered about the country, particularly in Western Japan–and some were in even more remote parts of the country in places that would be even harder to strike militarily.

For example, Shimazu Yoshihiro was based out of the remote south of Kyushu, with two wealthy and remote provinces to his name.

So while Ieyasu could have rolled the dice on continued military efforts against his defeated foes in order to eliminate them outright, he judged discretion to be the better part of valor. He had won, and rather than bet his chips again on the chance of winning bigger, it was time to cash out.

So Tokugawa Ieyasu began to make deals with his defeated rivals; he would let them live (often in reduced conditions) in exchange for their loyalty. Mori Terumoto, for example, had to give up three of his five provinces, including his fortress city of Hiroshima–which was handed over to a Tokugawa loyalist.

Shimazu Yoshihiro, being a bit more remote (and thus in a stronger negotiating position) was able to keep both of his provinces.

By 1603, Ieyasu felt secure enough to take the final step; he petitioned Emperor Go-Yozei to revive the old post of Shogun, which had laid vacant since Ashikaga Yoshiaki had been given the boot back in 1573, and grant it to him.

Ieyasu himself would hold the post for only a few years before abdicating in favor of his son, but continued to exercise behind the scenes authority until his death. His descendants would hold the position of shogun for the next two and a half centuries.

There was, of course, one final coda to be written in the story of Ieyasu’s rise to power. Just as Toyotomi Hideyoshi had initially risen to power while proclaiming his continued loyalty to the memory of Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu had maintained during his rise that he was loyal to the memory of Hideyoshi–he was fighting, he said, to remove “bad influences” from the young and impressionable boy. But, having taken the chance to become shogun, it was hard to argue that he had any interest in handing power over to the infant Toyotomi Hideyori (eight years old at the time of Sekigahara).

And it wasn’t like Ieyasu could just have just had Hideyori and his mother Yodo-dono killed; doing so would have invited discord within the Tokugawa camp among those with lingering pro-Toyotomi sentiments at a time when Ieyasu needed stability more than anything.

So, what to do with the boy?

The initial plan seems to have been to simply leave Hideyori alone and hope that, much as the children of Nobunaga had accommodated themselves to Hideyoshi’s rise to power (at least, those who hadn’t died), Hideyori would grow up to accept that Ieyasu was now calling the shots. Ieyasu left the boy and his mother Yodo-dono in Osaka castle, and allowed them some fairly generous fiefs to maintain themselves, though until Hideyori reached adulthood Ieyasu would hold those lands “in trust”. The hope was probably that Hideyori would grow up to be just another daimyo swearing his fealty to Ieyasu as shogun, much as Oda Hidenobu had grown up to be a follower of Hideyoshi’s.

Ieyasu tried a few other methods of securing Hideyori’s fealty in the long term. For example, the same year he became shogun he also pressured Hideyori’s mother Yodo-dono into accepting an arranged marriage between Hideyori and Senhime, Ieyasu’s grandaughter by way of his eldest son Hidetada and Hidetada’s wife Suugen’in.

Sugen’in, by the by, was Yodo-dono’s sister: the youngest of Oichi’s three surviving daughters by Azai Nagamasa, which yes did make Senhime and Hideyori cousins, but hey–that’s aristocracy, baby!

In 1611, Ieyasu would once again make a demand of Yodo-dono. Ieyasu (now “retired” in favor of Tokugawa Hidetada as shogun, but still largely calling the shots) was going to be in town (or at least nearby in Kyoto) for the enthronement of the new emperor (Emperor Go-Mizuno, number 108 in the traditional ordering), and “asked” that Hideyori visit him at Nijo Castle in Kyoto while he was in town. Yodo-dono was forced to agree, though she did secure some hostages from the Tokugawa family as protection.

That meeting, by the way, is often described as a moment when Ieyasu realized that Hideyori was no longer a youth; at 17 now, he was young and astute and a potential challenger to Ieyasu.

At least, that’s the story, though once again it’s hard to find much in the way of contemporary discussion of the meeting itself.

We do, however, have plenty of letters between Yodo-dono and her two sisters, married to a senior pro-Tokugawa daimyo and to the new shogun respectively. Those two sisters tried to convince their eldest sibling to accept the new order of things, but Yodo-dono remained fiercely opposed, and instead raised her young son with the notion that he should strive to reclaim his father’s birthright.

The decisive break came in 1614, when tensions were flaring high over a bell of all damn things. Specifically, Hideyori had been investing in repairs to both Osaka Castle itself (which needed some upgrades after a few years of neglect) and to Hokoji temple in Kyoto, a project funded by Hideyoshi in his own memory.

Ieyasu was deeply alarmed by the rebuilding of Osaka Castle’s defenses, and seized on a seemingly minor issue to force the issue once and for all — one of the bells Hideyori had commissioned for Hokoji. Specifically, the bell contained the phrase Kokka Anko inscribed upon it — meaning something like “nation at peace.” However, the phrase also contains the characters for the name Ieyasu — but divided by an intervening character, which Ieyasu suggested meant that Hideyori was implying that the only way to achieve a nation at piece was to chop Ieyasu up.

Ieyasu was clearly reaching a bit here; he’d come to accept that there would be no conciliation and that Hideyori would never come around to the new way of things, and so would have to be removed. On Hideyori’s side of things, a group of his councilors attempted to convince the boy (by this point in his 20s) not to pick a fight with Ieyasu, but the hardliners backed by Yodo-dono won out.

The result, in 1615, was one final battle, as Ieyasu mobilized his forces and marched on Hideyori’s fortress at Osaka castle, while Hideyori put out the call to anyone with a bone to pick with Ieyasu–join me and make a stand against the new order.

And quite a few people took him up on that–but not enough. The siege was hard fought over the course of months, but in the end, Ieyasu was victorious. Hideyori and Yodo-dono committed suicide together–the only survivors of Osaka castle were Senhime herself (whose release was negotiated before the final battle) and the couple’s only child, a young daughter who would become a Buddhist nun.

Ieyasu’s victory was complete–there would be no more challengers. He would die the next year at the age of 73, the ultimate victor of the age of unification.

Next week, we’ll look at the new order Ieyasu and his successors constructed.