This week on the Revised Intro to Japanese History: the beginning of the end of the age of war and the rise of Oda Nobunaga. How did Nobunaga go from the ruler of less than a single province to the most powerful man in Japan in just a few decades? And what do we really know about the man himself, his plans, and his vision for Japan’s future?

Sources

Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi.

Lamers, Jeroen. Japonius Tyrannus: The Japanese Warlord Oda Nobunaga Reconsidered

Lamers, Jeroen. The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga [Shinchou Kouki] of Ota Gyuichi

Asao, Naohiro. “The Sixteenth-Century Unification.” in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol IV: Early Modern Japan

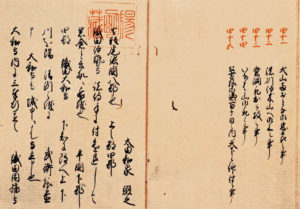

Images

Transcript

The story of the end of the civil wars and of Japan’s reunification after the Sengoku Era begins in Owari Province–now Aichi Prefecture–nestled along the coastal road between the Kanto plains and Kyoto.

And were you a gambling sort of person in the 1550s, with no foreknowledge of what is to come, this probably wouldn’t be the place you’d point to as the base from which the country would be brought back under unified rule. The preeminent family of the area lacked the wealth and resources of some of the other great clans of the age, and didn’t even fully control the province in which they were based.

Indeed, the Oda, as they were known, had extremely humble routes. Later, in the time honored tradition of all who rose to greatness in the warrior class, they would pay a well-heeled Kyoto aristocrat to forge a more illustrious genealogy for the family which went back to Taira no Kiyomori–one presumes as a deliberate slight to the Ashikaga shoguns, because remember they traced their ancestry back to Kiyomori’s ancient rivals in the Seiwa Minamoto.

However, that genealogy is most definitely a fiction intended to boost the prestige of the family rather than record anything approximating the truth. Instead, the Oda were a family of kokujin–a family local to Owari province, who had risen to power because they had, many centuries earlier, cut a deal with a more preeminent family.

That family was called the Shiba, and they were one of the great warrior families of medieval Japan–a clan of multi-province shugo aligned to the Ashikaga shoguns and with substantial influence at their court.

The Shiba were made shugo of (among other places) Owari province during their rise to power, and offered the Oda (as residents of the region) a role in helping govern Owari on behalf of the Shiga.

And that little arrangement was quite satisfactory for all involved–at least until the age of civil war. When the conflict began, the Oda (like many other kokujin families) realized that there was no particular reason that they had to be taking orders from the Shiba anymore, and so hatched a conspiracy with other Shiba retainers in different provinces to rise up and depose their erstwhile masters.

The fiction of loyalty to the Shiba was maintained into the 1500s–it was politically convenient, after all, in some respects, since it offered a semblance of legality to Oda actions in Owari–but practically speaking the Oda became an independent family.

Still, independence came with problems all its own–in this case, a splintering of the Oda family tree into two competing rival lines jockeying for control of different parts of the province. The Oda clan would spend more or less the first part of the 1500s at war with itself as a result–at least, until the rise of its most famous member, Oda Nobunaga.

Oda Nobunaga, born in 1534, was the son of Oda Nobuhide–who was the head in turn of one of those competing Oda branches, based in the southern part of Owari and known as the Kiyosu Oda after the castle that was their primary fortress.

His father Nobuhide was, to be completely frank, a pretty bad leader. He did not focus on trying to reunify Owari under his branch of the Oda clan, and instead engaged mostly in military adventurism in the neighboring provinces to decidedly bad results.

To the south, he ventured into neighboring Mikawa province, home to a small clan called the Matsudaira about which we will have much more to say later. The Kiyosu Oda and the Matsudaira jockeyed to little result over their borderlands.

As a result, the Matsudaira turned to a neighboring powerful clan, the Imagawa, and brokered what amounted to a protection deal with them–in exchange for which the young heir of the Matsudaira family, Matsudaira Motoyasu, was sent as a ward and hostage to the Imagawa. However, Nobuhide was undeterred and attacked the Imagawa as well, seizing young Motoyasu in the bargain. Apparently both he and his young son and heir took a shine to the kid, and eventually returned the boy to the Matsudaira–a fateful choice, given future events.

To the north, Nobuhide went all in on supporting the longtime ruler of neighboring Mino province (the Toki clan) against a new threat to their rule–a flamboyant ex-Buddhist monk turned oil merchant who had used his money to get into the hot new field of warmongering, by the name of Saito Dosan.

Saito, as a side note, is one of my favorite figures of this period even though he’s not really the most important. One day I am going to indulgently do an episode just on him.

Anywho–Nobuhide’s war against Saito Dosan was largely inconclusive (and did not succeed in saving the Mino clan). The main reason it matters is that part of the truce eventually brokered between both sides involved a marriage alliance–Nobuhide agreed to marry his son to Saito Dosan’s daughter, known to history as Nohime.

Beyond his decidedly middling military career, Nobuhide was also not great at the other side of samurai leadership in the 1500s. His focus on campaigning meant he had little time to spare for the boring work of administration: engaging in land surveys to get a sense of the taxable value of his domains, or building up a strong administration to handle the day-to-day running of government.

And this was pretty important work for the ambitious daimyo of the time–if you didn’t do land surveys yourself, the only other documentation you had for tax purposes were land registers from the old shoen estates, which were often centuries out of date by this point. And without a good administration, actually collecting the taxes you were owed could be challenging, particularly given how good peasant farmers could be at hiding taxable harvests from inspectors.

So when Nobuhide died in 1551 it probably wasn’t the worst thing imaginable for the Oda clan–but his heir Nobunaga was only 17, and while he’d been a part of his father’s campaigns and had some combat experience he wasn’t a commander, nor did he have much of a background in administration. More than a few Oda vassals were (justifiably, I think) concerned about how the young boy would do.

Now, getting a sense of Oda Nobunaga’s character is an immense challenge, primarily because the best sources we have for his career are from decades after the fact and were recorded mostly to put a shine on him. Those sources depict Nobunaga–and this is the common image you see of him in pop culture today–as a bit of a wild child early in his career, unconcerned with discipline, propriety, or just doing his job well.

How true that is, well, again, it’s hard to say. But certainly, it makes for a good story, particularly given how it supposedly ends. That story involves Nobunaga’s tutor, Hirate Kiyohide, who served Nobunaga as well as his father and grandfather.

Hirate apparently felt that Nobunaga’s conduct early in his reign was unbecoming of a lord of propriety — later stories would have Nobunaga acting particularly boorishly during his father’s funeral, showing up late and refusing to dismount from his horse, among other things. In protest, Hirate committed suicide, leaving behind a note to the effect that since Nobunaga clearly had learned nothing from him there was no reason for him to live. Nobunaga then went on to mend his ways, and erect a temple in Hirate’s hometown in his honor.

Again, it’s a great story, but there are reasons not to fully trust it–most notably, Hirate’s suicide took place in 1553, two years after Nobuhide’s funeral, so quite a while to wait if the goal was to send a message about propriety in mourning.

All we can say for sure is that eventually Nobunaga started to take his duties as daimyo seriously, and spent the next few years leading his first successful military campaigns against his wayward relatives, reunifying Owari under his control by 1558. Just in time too–because things were about to get spicy in his neck of the woods.

Owari province’s location along the coastal road connecting the Kanto to Kyoto meant the Oda were smack in the way of any powerful daimyo who got it in his head that he wanted to march on the ancient capital. But why, you might be asking, would anyone want to do that? Well, despite the functional nonexistence of any central government, the emperor and Ashikaga shogun were both powerful symbols of legitimacy for any clan who could get control of them), and of course the Kansai area in which Kyoto was located remained the most economically developed part of Japan by far.

And in 1560, the neighboring Imagawa clan set its sight on Kyoto to do exactly this.

Or at least, that’s the common story. Later chronicles of Oda Nobunaga’s life and the Oda clan’s history would say that the Imagawa, led by their ambitious daimyo Imagawa Yoshimoto, were setting out in 1560 to conquer Kyoto and depose the current holders of the city (the Miyoshi and Matsunaga clans, who had jointly seized control of the city a few years back).

Personally, I have my suspicions about the accuracy of that statement, because from the region we’re talking about to Kyoto is a distance of about 300 kilometers/200 miles–so not exactly a short march. And there was a good amount of hostile territory in the way–not just the Oda but Saito Dosan in Mino province before you even made it to the Kansai area proper.

That’s not to say that such an undertaking would have been impossible for Imagawa Yoshimoto–the Imagawa were an old family distantly related to the Ashikaga, and had peddled that relationship into control of three provinces along the Pacific Coast (Suruga, Totomi, and Mikawa). Yoshimoto had also secured his flanks by cutting deals with his powerful neighboring rivals.

Even so, I’m of the opinion that Yoshimoto’s likely goal was simply to make his three provinces into four by seizing Owari province from the Oda, and the whole “Yoshimoto planned to march all the way to Kyoto” thing was a later invention to add some extra stakes and grandeur to what came next.

Because, as you might be guessing if you have a grasp of foreshadowing, Yoshimoto would never make it past Owari. He entered the province with tens of thousands of sources–it’s hard to have much trust in the numbers given by sources from this period, but somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 soldiers is the common guess.

And by the way, you can really see the impact of the shifting patterns of warfare here–the shift towards equipping large numbers of ashigaru footsoldiers rather than relying on mounted warriors meant a massive increase in the size of armies themselves.

The Oda forces, meanwhile, are estimated at about 2000–and again, it’s hard to know how much trust to put into numbers from this period, but it’s fairly clear Nobunaga was substantially outgunned.

But Nobunaga was also a talented strategist–and his chief talent in that regard was a clever ability to read out the likely moves of his opponents and bait them into doing what he wanted. For example, when he’d crushed the last of the renegade offshoots of his own clan in 1558, he’d done so with a brilliant strategy–telegraphing a plan to attack their major fortress at Iwakura in a bid to get his opponents to rush out and meet him in the field rather than risk a prolonged siege. That’s exactly what they did–running directly into a trap Nobunaga set for them, because he had no intention of risking a siege against even numbers if he could claim the decisive upper hand in a field battle.

And here too, Nobunaga had a plan, which brings us to the summer of 1560 and the famous battle of Okehazama. Yoshimoto had his Imagawa army make camp at Okehazama, a spot about 30 KM (a little over 18 miles) from Nobunaga’s home base at Kiyosu Castle.

There, he is supposed to have ordered a musical performance for his troops to celebrate the progress made so far — and, like as not, to express his lack of concern at the possibility of resistance by the Oda to his invasion.

At the same time, Nobunaga was rallying his troops for an attack. Using his superior knowledge of the local terrain, he was able to get his troops into position to ambush the Imagawa while they were in camp — Oda scouts knew the terrain of Owari province better than the invading Imagawa, and thus were able to get into position without the Imagawa realizing they were there. From there, he launched a head on attack into the heart of the Imagawa camp — aided by a sudden rainstorm, which obscured visibility and made it hard for the Imagawa to realize just how small the attacking Oda force was.

The result was a near total collapse of the Imagawa clan defenses. Imagawa troops, caught totally off guard by an ambush, fled en masse rather than fight. The Oda were supposed to have a pitifully small army, and Imagawa scouts should have been able to spot any Oda forces on the way — yet here were the Oda, coming basically out of nowhere, launching a surprise attack, so clearly they must have a bigger army than anyone realized and it’s time to panic and get the hell out of dodge.

Imagawa Yoshimoto himself assumed that the commotion from the fight outside was drunken revelry from the celebration he himself had ordered; by the time he realized any different, it was far too late to do anything about it. Two of Nobunaga’s retainers cornered Imagawa Yoshimoto, and after a brief fight overpowered him, killed him, and decapitated him.

And this was pretty much the end of the Imagawa, because remember–no samurai, from the lower footsoldiers to the upper ranks of the class, really fought out of ideological loyalty, except maybe for direct relatives or VERY longtime retainers. Most were in it for the paycheck–and now the guy who signed them was dead. The Imagawa still had a numbers advantage–their losses had not been that heavy–but the survivors had no reason to fight.

In the aftermath, Nobunaga was suddenly one of the most important people in his part of Japan. He’d dealt the Imagawa a blow from which they would never recover (the clan eventually collapsed under renewed attacks from all neighbors nine years later), and grabbed Mikawa province in the offing (including its new ruler, the very same Matsudaira Motoyasu who had once been an Oda clan hostage–he’d been a general for Yoshimoto, but defected after his master’s defeat and pledged loyalty to Nobunaga’s side, bringing his home province with him).

From there, he shifted his attention north, bringing his newfound power to bear against Mino province. That province, remember, had been ruled by Nobunaga’s father-in-law Saito Dosan, a relationship resulting from a marriage alliance coined to bring an end to fighting between the Oda and Saito.

Saito Dosan, however, had in the interim fallen from power in spectacular fashion. In order to legitimate himself as ruler of Mino, he’d married the daughter of the former lords of Mino — but the son he’d conceived felt more connected to his mother’s family than to his father. In 1554, that son rose up and killed his father in the name of his old family, and was now the ruler of Mino.

That son, Saito Yoshitatsu, would be the next to fall under Nobunaga’s gaze. Ostensibly, Nobunaga looked to avenge an unforgivable act of patricide against his family’s ally — though for practical reasons, Mino was a compelling target in its own right. It was, after all, close to Kyoto, and could provide a base of operations for eventual expansion into that region.

Once again, we don’t actually know Nobunaga’s motives–maybe he really did feel that he was avenging his father in law in some genuine act of filiality. Somehow, personally, I doubt it.

The initial fighting, however, did not go great for Nobunaga, who mobilized his forces to march into Saito territory and was driven back several times. However, in 1561 Saito Yoshitatsu died suddenly and while on campaign

And I should note here that Yoshitatsu was not the last of Nobunaga’s enemies to die under somewhat unclear circumstances after some initial battlefield success against Nobunaga, leading to some pretty wild speculation about secret assassins and such–none of which, of course, we can prove, but all of which are just tremendous fun to speculate about.

Yoshitatsu’s death put the Saito into a death spiral; his successor was far less competent as a general, and slowly the Oda began to take control of Mino province. In 1567, the last Saito stronghold, Inabayama castle, fell to an Oda force–commanded, by the way, by a fellow of some importance to our story going forward, Hashiba Hideyoshi.

Hideyoshi, about whom we will have much more to say, was from a low ranking family but had earned his way into the Oda ranks by means of his personal skill and courage.

He’d actually gotten his start in warfare with the Imagawa, but had defected to the Oda before the successful ambush at Okehazama — clearly, he had seen something in Nobunaga that convinced him this was the guy to work with.

We know very little for certain about Hideyoshi before the 1570s or so; later biographers described him as making many enemies among the Oda retainers because of his skill and brilliance, leading him to outshine men with far superior pedigrees.

This is usually credited as Hideyoshi’s first great success; Inabayama Castle was close to the Oda border town of Sunomata, and Hideyoshi proposed a plan to secretly fortify Sunomata without the Saito realizing, allowing Sunomata to serve as a large scale military encampment from which to base attacks on Inabayama. This plan — over the objections of others who felt it was foolhardy — received Nobunaga’s approval, and worked like a charm. The Saito had assumed that any invasion force attacking Inabayama would not have the benefit of a nearby fortified base in which to store supplies and rest troops — that edge allowed Nobunaga’s forces time to get organized without fear of either running out of supplies or a Saito counterattack. Inabayama was thus swiftly defeated.

Crediting this idea to Hideyoshi is a later invention; it’s unclear how involved he was, if at all, in the plan.

The success of this plan is supposed to have catapulted Hideyoshi into the ranks of the most esteemed Oda generals; it also gave Nobunaga a new, very fancy castle, which he proceeded to make his personal base.

That castle was named Gifu Castle (the gi being the character for Qishan, the mountainous home base of the legendary first emperor of China’s Zhou dynasty) and it became Nobunaga’s new headquarters.

It was also around this time that Nobunaga began to adapt, for lack of a better term, a motto–a four character phrase that, for example, was engraved on his personal seal. That motto was tenka fubu–roughly “all under heaven covered by the sword”–which, frankly, makes his ambitions from this point onward fairly clear.

And increasingly, he had the resources to call upon to manage that ambitious goal. Nobunaga now had command of three provinces, and spent six years during his conquest of Mino on the profoundly unsexy but deeply important work of building up a strong administration to manage those territories while generals like Hashiba Hideyoshi managed the fighting. That administration, in turn, was important for fielding the armies he would need to accomplish his vision; remember, the footsoldier ashigaru who made up the majority of armies during this time were essentially mercenaries (and so, to be frank, were most elite samurai), and were advantageous mainly because they could be conscripted and trained in large numbers for comparatively cheap relative to the mounted warriors of old.

But training these men, paying them, and equipping them with armor and weapons–spears, bows, and by this point guns either purchased from the Portuguese or increasingly forged at domestic gunworks–was not cheap, not to mention provisioning these big armies for their marches. And so Nobunaga spent years on things like land surveys of his domains to effectively tax his peasants using updated productivity numbers, and on reorganizing administrative boundaries to make them more geographically contiguous (now that the old shoen were no longer a concern). It’s very unexciting bureaucracy, so we won’t spend much time on it–but it’ll be important down the line when opportunity came knocking.

Opportunity, in this case, took the form of one Ashikaga Yoshiaki, and as the name might clue you in on he’d come to Nobunaga from Kyoto. Yoshiaki, in fact, was the son of a former shogun–but not the eldest, and so had done the fashionable thing for second Ashikaga sons and become a Buddhist monk.

However his brother, the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiteru, was murdered in 1565 by the Miyoshi and Matsunaga clans, who had negotiated an alliance to control Kyoto and the shogun as puppet rulers. Yoshiteru resented this and had begun to plot a rebellion against them–he was caught, and killed for this “betrayal” of his masters.

Yoshiaki was convinced by this betrayal to come out of monastic life and claim the role of shogun for himself, making it his goal to drive his brother’s killers from Kyoto (who just propped up another Ashikaga shogun after getting Yoshiteru’s blood off the upholstery).

But Yoshiaki was missing something central to actually succeeding in this goal–an army.

In 1567, he decided that the upstart Nobunaga was his best chance (but not his first choice; he’d already reached out to three other clans before the Oda to no avail). Nobunaga, however, was willing to hear Yoshiaki out. And apparently, he liked what he heard, because in 1568 he ordered his forces to set out for the capital with Yoshiaki in tow.

The results were, to put it mildly, spectacular. Only one clan along his route of march, the Rokkaku, decided to try and stop Nobunaga’s advance–and they were swiftly crushed.

The Miyoshi and Matsunaga surrendered Kyoto itself after a brief skirmish, with the Matsunaga surrendering outright and the Miyoshi retreating to their homelands on Shikoku.

Before the end of the year, Ashikaga Yoshiaki was in Kyoto and had been declared shogun, and offered Nobunaga a role as his kanrei–essentially, deputy shogun, and second in command of the Muromachi shogunate.

I imagine most people observing these events assumed this had been Nobunaga’s plan all along–install Yoshiaki and control him from behind the scenes as kanrei. So they were probably pretty shocked when Nobunaga refused to accept the job.

And he didn’t just refuse it once; the very next year, Yoshiaki asked the sitting emperor Ogimachi (number 106 by the traditional count) to intercede and convince Nobunaga to take the job, and Nobunaga told the emperor no.

In general, Nobunaga seems not to have been interested in existing titles and privileges. His successors in unifying Japan would revive older titles and positions to claim and take legitimacy for themselves, but Nobunaga never accepted a title higher than udaijin–the minister of the right in the old civilian government of the court.

So ok, what’s up with that? Once again, we simply don’t know for sure–we don’t have any idea what was going through his head at the time. We have some guesses based on what we know if his personality, but they are by definition guesses.

Maybe he was unsure long-term what sort of political arrangement he wanted, and preferred to concentrate on warfare in the meantime rather than accruing titles and positions that might or might not be of actual use in the future.

Maybe he had some radical plan to upend the whole political order and didn’t want to commit himself to any existing structures.

We honestly do not know.

Regardless, this refusal–and Nobunaga’s general lack of interest in reviving the shogunate or showing anything like deference to Yoshiaki–led to growing tensions between the two men.

But there was little Yoshiaki could do about it, dependent militarily as he was on Nobunaga. And Nobunaga did not rest on his laurels after taking the city; he very quickly set about on a campaign to solidify his control of central Japan by either convincing or compelling local samurai clans to accept subservience to him. One clever maneuver he used to do this was an invitation to a banquet in Kyoto in 1572, hosted by Nobunaga at the command of the shogun. Invitations were sent to all the major families of the region–Nobunaga correctly surmised that nobody who mistrusted him or was plotting against the Oda would voluntarily go to a city Nobunaga controlled.

When one local daimyo, Asakura Toshishige, refused to attend, Nobunaga used the excuse to brand him an outlaw and destroy the Asakura, claiming their lands. When his own brother in law Azai Nagamasa, who had a longstanding familial alliance with the Asakura, attempted to stop him, Nobunaga crushed him too–over the objections of his own sister, who was taken alive but whose children (Nobunaga’s nephews) were executed at his own command.

If you’re at all familiar with this period, you know that Nobunaga has something of a reputation for ruthless cruelty, and you can really see why in moments like this. Similarly, the powerful temples of central Japan and the various ikko leagues attempted to resist his rule–Nobunaga responded by ordering his commanders to besiege the temples, massacre the defenders, and burn them to the ground. Kaga province north of Kyoto was a hotbed of the Jodo Shinshu ikko ikki leagues–supposedly, Nobunaga gave the order to crush the ikko ikki “yama yama, tani tani”, on every mountain and in every valley.

More prestigious opponents were not spared either; the monks of the ancient temple of Enryakuji atop Mt. Hiei arrayed their wealth and armies against Nobunaga in the 1570s, and in response Nobunaga besieged the centuries old complex and burned it to ashes.

Ashikaga Yoshiaki himself would end up being forced to flee Kyoto in 1573 after openly declaring himself against Nobunaga only to watch all his allies be crushed by the at this point experienced and well-trained (and well provisioned) Oda forces.

He’d end up wandering the county once again looking for allies to back him in returning to Kyoto–this time to far less success.

Within the decade, Nobunaga came to rule the central (and best-developed) third of the country, and had dispatched challenges from two of the most powerful lords of the region, Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin.

And no, we’re not going to have time to talk about the two of them–they’re famous figures from the period, but tragically not super relevant for our narrative here except in defeat.

I do want to note that both Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin were initially successful in their attacks on the Oda, only to then both mysteriously take ill and die on campaign–and again, we have no proof that anything untoward happened there, but once again one does have to wonder.

By 1580, Nobunaga was clearly on a path to bring the rest of the country under his control–admittedly, there was still a lot of country left to conquer, but given the volume of wealth and the number of warriors he could call on from his newly conquered lands, I think it’s fair to call it only a matter of time.

Nobunaga, however, would not live to see it done–in 1582, while in Kyoto after returning from a campaign to finish off the remnants of the Takeda clan, he was betrayed.

That betrayal came at the hand of Akechi Mitsuhide, a general who had come to Nobunaga’s service alongside the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki–Akechi had been a follower of Yoshiaki’s who had joined Nobunaga and then stuck with him over the shogun when the two…parted company, let’s call it.

What exactly motivated Akechi’s betrayal is unclear. Nobunaga had personally disparaged him, mocking his poetry (of which Mitsuhide was quite proud)–but that was also how Nobunaga treated everybody.

Probably more important was a campaign in 1577 that Mitsuhide led on Nobunaga’s behalf against the Hatano clan. Mitsuhide convinced the Hatano to surrender quickly in exchange for a promise of their personal security; Nobunaga, for reasons unknown, overrode Mitsuhide’s guarantee and had the Hatano leadership executed. The Hatano retainers felt that Mitsuhide had lied to and betrayed them, and responded by kidnapping and murdering Mitsuhide’s own mother. Mitsuhide, not without justification, blamed Nobunaga for his mother’s death.

In June of 1582, while Nobunaga was in Kyoto resting after his final campaign against the Takeda, Mitsuhide took his forces (which were supposed to march west to continue another war against the Mori clan we discussed two episodes ago)–and turned them on Kyoto instead. Nobunaga, residing in Honnoji, a temple in the center of the city, was killed when the temple burned–a fire set by Nobunaga to prevent his body from being recovered and desecrated. His eldest son Nobutada was killed in the fighting as well.

Now, Nobunaga’s legacy is deeply complex. Obviously, he set the stage for the reunification of Japan–next week we’ll look at the man who took over his lands and used them as a base to complete that reunification.

When he’s portrayed in pop culture–and this period is a BIG source of pop cultural material in the same way that, say, the Wild West is for the United States–Nobunaga tends to be shown as a pretty unambiguously villainous man. His unpleasant demeanor–he gave Hashiba Hideyoshi, the same man who won the siege of Inabayama for him, the nickname “monkey” as a way of making fun of his face–his casual brutality, his ruthlessness against his enemies, all lead pretty neatly into the image of a man obsessed with power and victory, and unfeeling about anything else.

There are other sides to him, however; the chronicles of his reign mention an absolute obsession with sumo, for example. In the span of two years, from 1580-81, he hosted no less than five tournaments in Gifu Castle, personally sponsoring them and paying for a prize for the victor.

He also loved tea–seriously, the man went out of his way to collect famous tea sets. He even bullied one of his retainers into handing over the same famous tea vessel–the tsukumonasu–we talked about back in episode 518.

He also regularly patronized masters of the tea ceremony–which we’ll have more to say about in the future–calling them to Kyoto to teach him the ceremony and prepare tea for him.

Beyond tea, the man was mad for anything with a history, from ancient swords to famous paintings.

Little moments like this are fascinating for getting a sense of Nobunaga’s personality beyond his propensity for violence, and they do make me wonder about the man himself, and how he saw himself and his role in events.

But of course, part of what makes him interesting (at least to me) is that we don’t have much from the man himself, and nothing about how he saw his motivations or goals.

Not that they matter much now that he’s literally dust on the win.