This week, we look at the flip side of the chaos of the Sengoku era in the form of two clans that rose to prominence from obscurity during the age of civil war. The first half is focused on the Mori family of western Honshu, while the second is focused on the Date, from the island’s remote north.

Sources

Mass, Jeffery P. The Bakufu in Japanese History.

Sansom, George B. A History of Japan, 1334-1615.

Gedacht, Anne Giblin. Tohoku Unbounded: Regional Identity and the Mobile Subject in Prewar Japan

Images

Transcript

Last week was all about great clans brought low by the period of civil war known as the Sengoku Jidai, or Age of Warring States. Today is all about the reverse: clans which rose from comparative obscurity to power, prestige, and greatness during the turbulence of war.

In other words, today is about the flip-side of that term gekokujo–the low conquers the high–that is so often associated with this age.

And I can’t think of a better place to start that conversation than with one of the most powerful families to emerge from the age of civil war–the Mori clan.

Now, the Mori clan have a pretty elite genealogy; they would claim descent from Oe no Hiromoto, a rather fascinating figure from the early age of samurai politics.

Oe was an aristocrat of Kyoto, descended from a long line of aristocrats who had served within the imperial government under various emperors.

However, Hiromoto himself is notable for turning his back, in a sense, on that tradition; in 1184, he received an invitation from one Minamoto no Yoritomo to travel to Kamakura in the remote east of Japan, and accepted.

Yoritomo was, of course, on his way to taking the title of shogun and setting up Japan’s first warrior government in the Kamakura bakufu. There was just one little problem; Yoritomo was trying to set up a warrior government, but did not have a lot of experience, you know, governing.

He was a politician–a man good at crafting alliances and building relationships–but not a bureaucrat who had a clear idea of how to run this new center of power he had promised to establish to advance warrior interests.

And so he reached out to several aristocrats of Kyoto with experience in the civilian government of Japan’s emperors, including Oe no Hiromoto–whose brother had already taken up in Yoritomo’s service, and who returned to Kyoto in 1184 to recruit more experienced bureaucrats to the future shogun’s cause. Naturally, he reached out to his own brother, and Hiromoto decided to take him up on the job offer.

Oe no Hiromoto would become extremely influential on the new Kamakura bakufu, as Yoritomo’s government came to be known, helping to set up the Mandokoro–essentially the administrative office of the Kamakura government responsible for collecting revenue and managing expenses.

Which is a pretty important part of, you know, running a government.

Oe no Hiromoto himself would be an advisor first to Yoritomo and then after his death to his wife Hojo Masako (who would come to more or less run the Kamakura bakufu behind the scenes) before his own death in 1225.

Hiromoto also had four sons, the youngest of which was named Oe no Suemitsu. As the fourth son, Suemitsu was not going to inherit leadership of the family after his father’s death, but in the 1200s inheritance laws were a bit more equitable than they would later become–every one of Hiromoto’s children would get something.

And so Suemitsu, in the tradition of the time, took what he got from his father’s inheritance and established a new branch of the family. He also took a new surname to distinguish his line from the main Oe branch, taking the name of the most valuable shoen, or tax free estate, his father had bequeathed to him. That shoen was called Mori, in what was then Aiko County, Sagami province–today it’s more or less Kanagawa, just to the south of Tokyo.

Mori Suemitsu, as he is known, became the ancestor of a family that, over the course of the Kamakura years shed their aristocratic identity and took on the identity of warriors–the line between those roles still being somewhat fuzzy at this point.

They were not, to be frank, particularly important during the Kamakura years, serving as one of many gokenin, or direct retainers of the shogun. Over the century or so of Kamakura rule, they spread all over the country, with the Mori line breaking into various branches of its own.

As a result, when the Kamakura government came crashing down in the 1330s, different branches of the Mori found themselves on different sides of the subsequent fighting.

Fortunately, only one of those various branches matters to our story. That branch was descended from Mori Tokichika, who in the later Kamakura years actually did attain a position of some prestige as one of the senior members of the Rokuhara Tandai–the agency of the shogunate responsible for keeping an eye on things in Kyoto. However, Tokichika was eventually forced to retire by a political rival who boxed him out of power, and spent the rest of his life in political seclusion in Kawachi province, where according to some legends he met a young warrior by the name of Kusunoki Masashige and taught him the art of battle.

Mori Tokichika’s son and grandson would, during the wars between the northern and southern court that came after the fall of the Kamakura government, side with the southern court and its renegade emperor Go-Daigo. However, Tokichika’s great-grandson, Mori Motoharu, would defy the rest of the family and join Ashikaga Takauji, possibly instigated to do so by his great-grandfather.

Or I should say he would eventually; Motoharu was only 16 when the war between the northern and southern courts began.

Still, he grew into the role of an adept commander, serving the Ashikaga with distinction–and in particular was a part of the invasion force sent in the 1370s to subjugate far off Kyushu, which had become a bastion of southern court power during the civil war.

Motoharu was also responsible for bringing his family to the place they are most associated with. By the early 1300s, the Mori clan had thanks to its service in government acquired estates and landholdings all over Japan, from the Kanto plains to remote Echigo on the Japan sea coast to the Chugoku region of western Honshu.

Motoharu in particular inherited a shoen estate called Yoshida in what was then called Aki province (now Hiroshima prefecture in the Western part of Honshu), and over the period of war between the northern and southern courts decided to settle out there to manage his lands directly. His descendants would remain in the area of Yoshida as kokujin, warriors whose local presence made them influential in the region and responsible for managing affairs in the provinces –but who were not a part of the elite class of shugo families who dominated the government of the Ashikaga shoguns.

And there the Mori family remained until the rule of the Ashikaga shoguns began to collapse in the 1460s. And at the start of the age of civil war, the Mori were in an EXTREMELY precarious position. They were moderately powerful kokujin, to be sure, but they were surrounded by other kokujin families who were looking to take advantage of the chaos to expand–not to mention several powerful shugo families with multiple provinces of land to their names. Most notably the Ouchi and our old friends from last week, the Yamana clan, were both powerful multiprovince shugo in Western Japan at the start of the age of Civil War.

Which made the position of the Mori tenuous, to say the least–any one of their powerful neighbors could make a play to gobble them up.

Thus, for the first few decades of the Sengoku years, the Mori clan leadership spent most of its time and energy simply trying to survive against powerful enemies like the Yamana and Ouchi–or against branches of the family, as continued splits within the family line threatened the occasional internal clan war.

It wasn’t really until 1523 when the clan really emerged as a serious contender in the power politics of the time–led by Mori Motonari, 26 years of age at the time.

Motonari’s life had already been, to put it lightly, a wild ride. He was the second son of Mori Hiromoto, the head of the main Mori clan branch, and an…uninspiring leader, let’s put it.

And what I mean by that is that Hiromoto got his butt whupped by the neighboring more powerful Ouchi clan in a fight early in his second son’s life–and agreed to step down as part of the peace deal, going into retirement and then proceeding to drink himself into an early grave. One of his father’s vassals took over the family castle and banished the young boy, who earned the nickname kojiki wakadono–the beggar prince, roughly translated.

By this point, family headship had passed on to his brother, Mori Okimoto–but in 1516 Okimoto died under unclear circumstances. Motonari became guardian of the new family head–his nephew, Mori Komatsumaru. But in 1523 the sickly young boy died, and the remaining vassals of the Mori family settled on Motonari to lead them.

And this proved a prescient choice, to put it mildly. Motonari had already established himself as a talented warleader; even before taking command of the clan, he’d fended off an invasion from the neighboring Aki-Takeda family (unrelated to the more famous Takeda of central Japan).

Proven talent as a winner was important for a daimyo, because war during the Sengoku age was deeply mercenary. To be fair this had always been the case, as we’ve seen in past episodes–but particularly in the Sengoku era, the ability to win was essential to continued survival, and not just to avoid invasions from a neighbor.

You may have noticed that samurai in this period did not feel themselves bound too tightly by notions of honor and duty–certainly that language got used a lot, but most vassals were not above replacing a master who was unable to pay them consistently. Clever administrators would arrange for their warriors to have fixed stipends, but you know how it is with people wanting annual raises–I mean, cost of living adjustments just are what they are, people.

So being able to keep your vassals happy required either more effective exploitation of your own lands (and there’s a limit to how much you can do that) or, more easily, taking land from a neighbor.

The majority of your army in this time, to be fair, would not be professional, mounted samurai–over the course of the Sengoku years, military forces shifted away from small elite bands of warriors to a more infantry-heavy approach dominated by ashigaru–footsoldier conscripts who were often not even from warrior families at all. Instead, they simply pledged themselves to some such vassal or lord in exchange for a paycheck.

And ashigaru have many advantages–they’re cheap to outfit compared to a full mounted warrior, and don’t take much to train. One famous document from this period, the household laws of the Asakura clan, enjoined future daimyo: “Even if you own a sword or dagger worth 10,000 pieces of silver, it can be overcome by 100 spears each worth 100 pieces. Therefore, use the 10,000 pieces to procure 100 spears, and arm 100 men with them. You can in this manner defend yourself in time of war.”

To quote a much later general on the same subject: quantity has a quality all its own.

But these guys too had to be paid–and so we’re back at the same problem. Victory–and the cash it provided–was essential to funding a military, which you in turn needed to make sure one of your own neighbors didn’t decide that you made a tempting pinata to whack until a paycheck for their retainers fell out.

As the clan’s new daimyo–its territorial lord–Mori Motonari would prove he was in fact a winner, leading his family to enormous prosperity and power over the course of 50 years.

Still, things didn’t start off particularly promising; immediately upon taking power Motonari had to win a civil war against his own half-brother and a group of vassals who preferred said half-brother (and executed all of them when he won–family is complicated sometimes).

And shortly thereafter Aki province was invaded by a powerful neighboring family, the Amago, who forced Motonari into vassalage at swordpoint.

Still, despite what I think can fairly be called an unfortunate start, Motonari’s position was better than it seemed. In particular, the Amago did not offer particularly harsh terms–because they wanted to secure the province in the face of a nearby rival, the powerful Ouchi clan, which controlled the Western tip of Honshu.

Motonari took advantage of this, accepting vassalage and playing the part of a loyal Amago follower–while carefully seeking out those disgruntled with Amago rule and recruiting them to his cause.

In 1525, Motonari led a mass defection of Amago clan vassals to the Ouchi, landing a massive blow against his ostensible masters–and of course securing great terms with the Ouchi, who were more than happy to welcome such a talented young leader into their service.

The Ouchi clan themselves are actually a pretty interesting story; much of their power as a clan was based not on land but at sea. Their position along the calm waters of the Seto inland sea was very strategic–all trade headed to Kyoto from either Kyushu or the mainland of Asia had to pass by them–and the family had invested in both a substantial fleet and in friendly relations with the bands of pirates who roamed the area.

They also held control of the all important kango, or tallies–a subject worthy of a good tangent in its own right.

By this time, China–the most powerful civilization in Asia, and arguably the whole world–was ruled by the Ming dynasty, founded in the 1300s by rebels who had freed the region from Mongol rule. The first Ming Emperor, known to history as the Hongwu Emperor, had envisioned a harmonious and largely insular society, and viewed foreign trade with suspicion–and as a result tried to restrict it heavily. Only vassal kings acknowledged by Ming emperors could trade, and only at fixed intervals.

The Ashikaga were among these vassal kings, thanks to Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s prudent but much maligned decision to accept nominal submission back in the 1400s. As a result, Ashikaga shoguns were issued a book of kango, or tallies.

Those talley books were full of one copy of a sort of trade certificate issued by the emperor, saying that in year X of the reign of the Ming emperor Y representatives of king Z were allowed to come to this port (for the Japanese Ningbo on the central coast) to trade. You had to bring the talley with you, and when you did it was matched by a local official against an exact copy kept by the emperor’s government. When an emperor died, new tallies were issued–with the “swap” happening the next time a country sent a trade mission.

After the Ashikaga government began to collapse, it was the Ouchi who managed to make away with the tallies, and who had been using them to conduct enormously lucrative trade with China “on the shogun’s behalf.”

What I’m getting at is that the Ouchi were kind of a big deal, and Mori Motonari seems to have been either content to serve them or unable to see a way to avoid it, and stuck by the family loyally until the 1550s–when the Ouchi suddenly and spectacularly imploded.

Part of the issue was that the wealth of the China trade dried up. In 1523, the Ouchi sent a trade mission to Ningbo–but so did the rival Hosokawa clan, who we talked about last week.

After a scuffle between these two clans over Kyoto, the Ouchi came away with the current set of kango tallies for the reign of the Zhengde emperor–but the Hosokawa nabbed an older set from the reign of the Hongzhi emperor.

Both clans sent trade missions which arrived at the same time, and which then ended up fighting each other in a street battle in the Chinese port.

This was not the first time Japanese traders had made a nuisance of themselves–in one previous instance Ouchi merchants had paid to have a Chinese merchant who stole from them assassinated, and in another the Japanese delegation got into a fight with another diplomatic delegation for unclear reasons–but it was the last straw.

Japanese merchants were banned from Chinese ports–that ban wasn’t officially lifted until the 1800s.

Which was not great for the Ouchi clan, dependent as they were on that trade income. Also not great for them–the mental collapse of their leader, the daimyo Ouchi Yoshitaka.

Yoshitaka took the reigns of the Ouchi in 1529 and was initially a pretty brilliant warleader–but suffered a series of brutal defeats in the 1540s, including one where his heir was killed in the fighting. He began to sink into despondency and neglect actually running his territories, leaving the Ouchi listless and leaderless.

And of course from there it didn’t take very long at all for Yoshitaka to lose the confidence of his vassals; in 1551, one of his most talented generals, Sue Harukata, rose up and deposed Yoshitaka (who was forced to commit suicide).

Mori Motonari was initially unable to do much about this–and while the later histories of the Mori clan would protest that Motonari was loyal to his master and simply held back out of a strategic understanding of the balance of power, it’s a bit hard for me at least to escape the sense that Motonari saw all of this as useful.

After all, “avenging his master” would provide all the excuse Motonari would need to rise up and take power for himself–and to do so with a degree of cover for what would other wise be a flat out usurpation.

We don’t precisely know what Motonari was thinking, of course–though certainly I lean towards the more cynical interpretation–but regardless, what comes next is clear.

Motonari bid his time for five years before declaring war against Sue Harukata–whom he accused of usurping the rightful power of the Ouchi–and marshalling his forces.

He’d spent the intervening years preparing for this moment, of course, and the plan he set into motion was, I think it’s fair to say, a pretty good one.

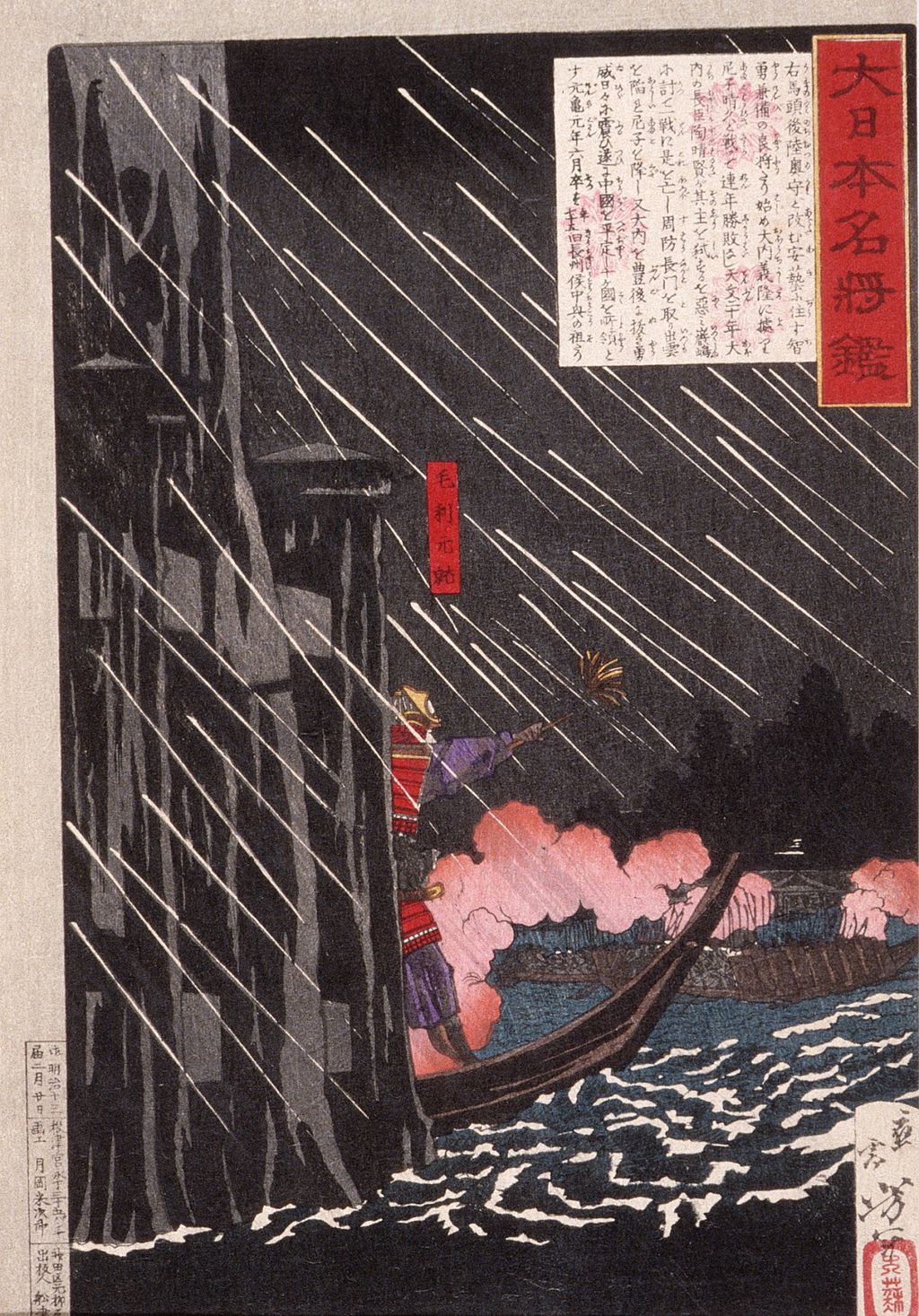

Motonari had decided from the jump where he wanted the climactic battle of his war to take place: Itsukushima, an island off the coast of the Mori family holdings in Aki province.

This island, also known as Miyajima (literally “shrine island”) is today a picturesque world heritage site–Itsukushima jinja, the main shrine on the island, is the one with the red torii gates built in the water, and honestly if you’ve ever seen tourist or travel photos from Japan you’ve almost certainly seen it.

It’s also, like Nara, home to a wild deer population that is allowed to move about freely–and like Nara, the little bastards are quite willing to take advantage of unsuspecting tourists. One of the little bastards ate my map right out of my pants pocket the first time I went.

In the 1550s, however, Itsukushima was less known as a tourist trap and home to some ill-tempered wildlife, and more as a strategic island in the middle of the shipping lanes across the inland sea, as well as a major trade hub.

Motonari’s plan was to move his forces there to convince Sue Harukata to launch an attack in the hopes of crushing the rebellion in a single blow, and then abandon the island. Why abandon it rather than make a stand? Because the Mori had a substantial fleet at their disposal, and could trap the attacking Sue force on the island and annihilate it in one fell swoop.

To supplement his navy, Motonari even cut deals with the pirate clans of the inland sea just like the Ouchi had before them. Most notable among these were the Murakami, a massive pirate band with roots going back to the 1100s who were by this time one of the largest pirate groups in the country.

They’d even begun to claim titles and grandiose for themselves, though they had no legitimate legal claim to them.

Motonari begged for their help, going so far as to marry one of his sons to a Murakami daughter. It’s not actually clear whether the Murakami took him up on this, because after the age of civil war the Murakami were legitimated as a warrior family and rewrote their family histories to make it seem like they had always been loyal to Mori Motonari (which we know is not true from the surviving historical record). It seems likely that at least a few branches of the group did come to his aid, at least.

With their help, Sue Harukata was indeed crushed, and within a few years Mori Motonari was able to roll up the remaining Sue territories and make himself into the new master of Western Honshu.

Motonari would ostensibly retire as daimyo in 1557 in favor of his eldest son, but practically this was more of a “training wheels” exercise to allow said son to get used to leadership while daddy dearest continued to call the shots. Motonari would actually outliv that son (who died in 1566) and see his own grandson installed as daimyo before his death in 1570. By that time, he was the master of no less than eight provinces along the Western coast of Japan–an absolutely meteoric rise to power for someone who had been a vassal a decade and a half earlier.

We’re going to leave the story of the Mori clan there because we’ll pick it up a few episodes down the line, and take a look at the story of another clan that rose from obscurity in the Sengoku period–the Date, all the way on the other end of Japan.

Like the Mori clan, the Date claimed for themselves an illustrious heritage, stretching back to the Northern branch of the Fujiwara clan–a branch of Kyoto’s greatest aristocratic family, who had for a time used their influence to conquer and personally rule the northernmost part of Honshu before being crushed by Minamoto no Yoritomo during his rise to power.

Unlike the Mori clan, from what we can tell this illustrious genealogy was completely made up. Which, to be fair, was not uncommon. The vast majority of the powerful samurai families that emerged during the age of warring states were more akin to the Date than the Mori–they were minor provincial families of warriors rather than descendants of the major warrior clans of pre-civil war Japan.

However, when the age of civil war ended, many of these families simply made up histories that gave them a more illustrious backstory–in essence, claiming legitimacy for themselves by inventing a more glorious origin story out of nothing.

In the case of the Date, their history pretty clearly traces not to the Northern Fujiwara but to one Tomomune, a warrior who was among the gokenin, or personal retainers, of Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first shogun of the Kamakura bakufu back in the late 1100s.

For his loyal service to Yoritomo, Tomomune was awarded a shoen–a tax free estate–in Mutsu province in the far north of Honshu. The main village of that shoen was called–you guessed it–Date, and thus he changed his name to Date Tomomune.

As a side note, you sometimes see his name written as Idachi Tomomune or Idate Tomomune–these are variant names of the same place that were used from what we can tell pretty interchangeably. That said, Date is the most famous name associated with the family, so for ease of recognition I’m just going to stick to that.

Now obviously, being rewarded for service by the first shogun was a big deal, but it’s important to note here that Date Tomomune was not what you’d call a famous figure by any stretch. Mutsu province was not exactly a prime posting; the largest of the traditional provinces, it covered parts of what’s now Fukushima, Miyagi, Iwate, Aomori, and Akita prefectures, and was basically the right half of the northern tip of Honshu. To put it somewhat impolitely, it was the middle of nowhere–the sort of place the Kamakura bakufu cared about only because ignoring the region could make it into a base for bandits or anti-government subversives.

And Date Tomomune wasn’t even the shugo of this remote province; he was a gokenin (a direct vassal of the shogun) and jito, responsible for policing the estates of the region.

Still, one supposes a job is a job, and for over 100 years the Date served the interests of the Kamakura bakufu loyally.

In the 1300s, the clan leadership came down on the side of the Southern Court and Go-Daigo in his war against the Ashikaga, and–rather unusually for a samurai family–continued to back that cause loyally all the way to the end.

Seriously, from what I can tell they didn’t even try to switch sides once, which is frankly astonishing compared to basically everyone else.

Obviously, not a great job picking a side to be ride or die for, but the Date did have one big advantage–Mutsu province was the ass end of nowhere, and so actually sending an army to deal with them was a huge pain that nobody wanted to deal with.

Seriously, the war ended in the 1390s but the Ashikaga shoguns didn’t even bother bringing the Date to heel until 1415! And even then, they got away with a slap on the wrist–no more supporting renegade emperors! In exchange for a promise of loyalty, the Date clan leadership was granted a great deal of influence in Mutsu (though not the title of shugo of the province). Presumably, removing them from power required more of an investment of time and energy than anyone wanted to bother with, and so a favorable peace deal was in the cards.

When Ashikaga rule in turn broke down in the 1460s, the Date clan once again was insulated by fortunate geography. The fighting in the north was limited (presumably because once again it was so remote that the region was not seen as worthwhile), and so the clan faced comparatively few threats to its rule. In turn, for much of the age of civil war, the Date were very much a sideline presence–content to manage their existing territory, fight the occasional skirmish over borderlands, and focus on issues of internal administration rather than throwing themselves into the battle for control of the country.

At least, that was true…until Masamune.

Date Masamune is probably one of the most famous figures of this period, both for his accomplishments and for his iconic look.

A childhood illness–smallpox is the most common explanation–disfigured his face and left a massive scar over one eye, which he wore an eyepatch to conceal. He also, and this might sound ridiculous but it is true, had an absolutely incredible hat.

Seriously, if you look at the kabuto–the helmet–for his armor, it is instantly recognizable. There’s a giant crescent moon on it that looks for all the world like some anime craziness but it is real.

To be fair, the wearing of outlandish helmets was not unique to Masamune; other leading members of the warrior class had similarly stylish signature getups, the idea being to broadcast one’s presence on the battlefield both to inspire the troops and demonstrate your own courage in a “come at me bro” sort of way.

If you see that giant crescent moon floating around the battlefield, you know Masamune is on the scene–and if you come for the king, my friend, you best not miss.

Still, before he was a general known for his excellent taste in headware, Date Masamune was just a young man–the eldest son of Date Terumune, who became the clan’s daimyo in 1578. Terumune was an impressive leader in his own right; a talented general, he managed during his life to both expand the Date clan holdings in Mutsu and maintain friendly relations with the most powerful neighboring clans in other provinces, including an up and coming fellow named Oda Nobunaga about whom we will have plenty more to say in the future.

Terumune was also an able administrator; he invested a great deal of his tenure in office into not war (though there was plenty of that too, and he did expand the clan lands during his tenure) but into surveying territories to ensure he was getting his fair share of taxes (that is to say, as much as he could possibly get).

In 1584 Terumune retired and handed off the position of daimyo to his then 17-year old son Masamune, the idea being once again a sort of “phased transition” of the leadership.

The idea was to ensure some sort of stability in the leadership transition–like Mori Motonari, Terumune wanted to ensure his successor had a “training wheels” period of getting adjusted to a leading role.

Unlike Mori Motonari, Date Terumune’s attempt to do this would go astonishingly poorly.

To be fair, it wasn’t really Terumune’s fault. One year after his retirement, Terumune decided to step in and help his son negotiate with a neighboring daimyo, Nihonmatsu Yoshitsugu. The Date and Nihonmatsu clans had been fighting on and off for a while at this point, and both sides were now looking to negotiate a truce–Terumune decided to take this on personally, given the delicate nature of such negotiations.

It’s not totally clear how this happened, but during the negotiations between Terumune and Nihonmatsu Yoshitsugu, Yoshitsugu decided to kidnap Terumune. His precise thinking is not clear to us–was this the plan from the jump? Did he just not like the offer he was getting? Regardless, it seems pretty clear Yoshitsugu hoped to use Terumune as leverage to get what he wanted–a better peace deal with the Date.

If that was the plan, though, well…gotta say it didn’t go great.

When Masamune got word of his father’s kidnapping, his first thought was not “time to negotiate for his release” but “time to chase Yoshitsugu down and kill him.” And to be fair, he did manage to do this–but in the ensuing scuffle, his father was killed as well.

Which was terribly tragic…or was it? Pretty much since the moment this happened, there have been some who suggested that Masamune deliberately got his father killed or even killed him personally–after all, with Terumune gone Masamune’s control over the clan was no longer limited. The “training wheels”, so to speak, had been taken off.

Indeed, his own mother (known to history as Yoshihime) came to believe this, and in some tellings began to conspire with some Date clan retainers to remove Masamune from office by poisoning him and replace him with his younger brother.

Masamune handled this calmly and rationally when he got wind of it, by exiling his mother and decapitating said younger brother. Which yes, is effective in terms of the immediate threat but not really a great way to beat the “I would murder my own father to seize power” allegations.

Masamune spent years on campaign against the Nihonmatsu aiming to wipe them out–to “avenge his father”, of course, but also to expand his power base in Mutsu province.

And when this dragged him into war with other neighboring clans–who not unreasonably began to fear that they would be the next targets of this expansionist teenager–Masamune made war against them as well.

His approach to war was also singularly brutal; one of his earliest campaigns, against a vassal who had declared independence from the Date because he did not wish to take orders from a teenager, ended when Masamune captured said vassal’s castle and ordered everyone inside executed–even though they had surrendered once it was clear they were beaten. And keep in mind, this isn’t just an act of violence; all these warrior families have been intermarrying for generations, so like as not pretty much all the senior commanders are related to each other on both sides!

Masamune’s expansionism did not win him many friends, but by 1590 they did see him crush most of his opposition and in full control not only of the massive area of Mutsu but parts of its southern neighbor in Aizu province as well. Reunification–which we’ll get to in the future–would see the end of his expansion, but regardless Masamune had taken the clan extremely far in a very short span of time.

And frankly, both he and Mori Motonari are great examples of the kind of person who tended to get ahead during the age of civil war. Though they both dressed their actions up in kind-sounding language– “avenging a betrayed lord”, “dealing with my father’s killers”, all that good stuff–in reality they were about as cynically self-serving as you can get in their actions. They were, to put it simply, morally flexible, ambitious, and very open to the possibilities of violence to advance their agendas.

And yet, it’s worth noting that for all their worldly glories, it was not these two men–or the many others whose stories are like theirs, but who we do not have time to talk about here–who came out on top, so to speak, of the civil wars. And I think there’s a clear reason for that.

Next week, we’ll begin looking at the so-called three unifiers of Japan, who will bring an end to the civil wars. And they too will be ruthless and violent and all those things–but they’ll be one other thing that I think tends to escape notice when we think about this period. They will be booksmart administrators who understand, to quote a thinker from a very different time on the other end of the world, that the sinews of war is infinite money.

Simply put, they were nerds. Deadly, violent nerds.