Part four of our Revised Introduction to Japanese History is all about the Taika Reforms of 645 CE: what drove them, why do they matter, and why does the more traditional answer to those questions leave some important gaps in our understanding?

Sources

Mitsusada, Inoue. “The Century of Reform”, in The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol 1: Ancient Japan

Fuqua, Douglass. “Centralization and State Formation in Sixth- and Seventh-century Japan” and Bruce L. Batten, “Early Japan and the Continent” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850. ed. Karl Friday

The JHTI Nihon Shoki translation

Images

Transcript

When I was back in graduate school, oh so many years ago, my PhD advisor Dr. Ken Pyle had a line he’d pretty much always use whenever he got the chance in lectures, or public talks, or what have you.

He would say that there are three decisive turning points in Japanese history, moments that saw the structure of Japanese politics and society change decisively.

And for him, the important thing about those moments was that they all were “triggered”, so to speak, by contact with an outside power. The second two on the list were the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and the American Occupation of Japan from 1945-1952–about which we will certainly have more to say much further down the line. For Dr. Pyle, both of these were decisive turning points in the evolution of modern Japan, and both were central to what’s arguably his most famous work–Japan Rising–which contains as a major sub-argument the idea that much of Japan’s political history has been shaped by forcible contact with stronger external powers.

The very first of these turning points, meanwhile, he dealt with only really in passing, as proof of the trend (so to speak) of change driven by contact with the outside as a motif in Japanese history that goes beyond the last two centuries. And to be frank, that’’s not unusual–within history as an academic discipline, there’s generally a pretty steep divide between what we’d call modern and premodern historians (with that split placed somewhere around 500 years ago; before that is premodern, after is modern). As a result, it’s pretty uncommon for modern historians to have much beyond a basic knowledge of premodern history required to teach intro courses (generally premodernists get it worse and are required to know more modern history, because their periods of specialty are often less in demand for the intro classes that make up the bulk of offerings in a given university).

Which is me acknowledging in a roundabout way that premodernists do often get the short end of the stick academically–and, being much more familiar with premodern Japanese history than I was 10 years ago, I can now decisively say this is unfair and does nobody a service.

Anyway–I don’t necessarily endorse the view that the three turning points Dr. Pyle called so central necessarily are, as I think it depends a lot on what you’re choosing to emphasize as ‘important’ about Japanese history. Even so, it’s hard to deny that all three of those points–and especially the very first, the so-called Taika Reforms of 645 CE–did not represent moments of substantial change in Japanese history.

Indeed, the word “Taika” literally means “great change”–which says a lot all itself, doesn’t it?

And by the way, I’m like 90% sure I told that exact same story as a framing device when I did this last time 10 years ago, but hey–I think it’s a pretty good one, in my defense.

Anywho: what are the Taika reforms, and what makes them such an important moment of change in Japanese history?

To talk about this, we have to take a brief trip away from Japan’s home islands, and hop over to the continent for a spell–because things on the continent are about to change too.

As we established a few episodes ago, the various divided kingdoms of Japan first made contact with the Asian mainland, and specifically with China, some time around 2000 years ago. This was right in the middle of China’s Han dynasty–which is generally considered to be one of the golden ages of imperial China. However, by the time contact became more regular, the Han dynasty was distinctly in its eastern, or latter phase–a period where the dynasty, which was already far less centralized than later ones, was faltering and losing ground to powerful regional lords who would, by around 200 CE, more or less dispense with it altogether.

What followed was about 400 years of division within China: first, the famous three kingdoms era (if you are familiar with the classic work Romance of the Three Kingdoms and its various derivative movies, books, video games, TV shows, and so on, this is what it’s based on), then the short lived Jin dynasty, then the sixteen kingdoms, then the northern and southern dynasties.

These are very important moments in Chinese history–for example, it was the constant pressure of war that drove the migration of Han Chinese, the ethnic majority of the country, out of their homelands around the Yellow River and south towards the Yangzi river and beyond. However, for our purposes, what matters about this is that for the 400ish years when the rule of the Yamato kingdom–the power base of Japan’s emperors–was coming together, a fragmented China did not represent a substantial political threat.

Neither, for that matter, did Korea. From the time of Korean prehistory, the peninsula had never been unified–instead, it had been home to a combination of divided Korean kingdoms as well as Chinese commanderies (the administrative divisions of the Han dynasty). As we’ve established, the competition between those Korean kingdoms, and their constant wars against each other, both drove Korean immigration to Japan (spreading continental technology and culture in the process) and provided an opening for the increasingly powerful Yamato kingdom to involve itself in Korean politics to its benefit.

However, by the mid to late 500s CE–right around the same time that the Soga clan was securing its hold over the court as we described last episode–the winds of change were blowing on the Asian continent.

First, in 581, a new figure rose to prominence in China. His name was Yang Jian, and for most of his life he’d been a general in one of China’s many fragmented kingdoms at the time–the northern Zhou. His talent for war had led to a meteoric rise within a kingdom dominated by an ethnic group descended from steppe nomads called the Xianbei, despite his own mixed Xianbei and Han Chinese ancestry. By early 581, the illness of the northern Zhou emperor had led to Yang Jian being appointed regent of the dynasty, at which point–in a move that, frankly, pretty much anyone who had watched at least one season of Game of Thrones should have seen coming–Yang promptly usurped his ruler and declared himself the new master of a renamed Sui dynasty.

Yang Jian–having restyled himself Emperor Wen (literally “the cultured) of Sui–promptly went a’ conquerin’, and that talent for war and violence meant that by the end of the decade, China (which at this point did not include places like Tibet, Xinjiang, or Manchuria) was reunited under his rule.

The Sui dynasty itself was not terribly long lived; despite his “cultured” name, Emperor Wen was a tyrannical ruler whose authority was built more on his willingness to cut the heads off people who disagreed with him than anything else.

Which makes you wonder why he wanted to be known as “the cultured”, but I guess history is written by the victors–or at least by the people who are willing to decapitate you if you don’t use their preferred nicknames.

The fact that Wen’s authority was built mostly on fear meant that after his death in 604, when his just as cruel but less competent son Emperor Yang took command, it did not take too long for things to start falling apart. Both emperor Wen and his son and heir Yang launched a series of wars against neighboring powers–by the first decade of the 600s the Sui dynasty was at war with the Champa of what’s now Vietnam, with the native peoples of what’s now Sichuan province, with the Turkish tribes on their northwestern border, and with the kingdom of Goguryeo in Korea–and while some went fairly well, the Korean war in particular was disastrous.

It turns out that Korea is a narrow peninsula full of mountain passes that are both easily defensible and inhabited by people who are really not very interested in being a part of China, thank you very much.

The disastrous wars, combined with high taxes to fund them and massive labor demands for huge construction projects (like an early version of the grand canal between the Yangzi and Yellow Rivers) led to rebellions against the dynasty. By 618, Emperor Yang was killed in a palace coup by one of his generals (I guess time really is a flat circle), and just a few months later the Sui itself was overthrown.

This did not, however, lead to the country fragmenting once again. Leading the anti-Sui charge was Li Yuan, a provincial governor whose family had served the Northern Zhou before it had been overthrown. Just as ambitious and talented–but less cruel–than Emperor Wen, Li Yuan was able to take the reigns of power for himself, and (restyled as Emperor Gaozu, or “the Great Ancestor”) established a new dynasty, the Tang.

The Tang dynasty is the second golden age of imperial China in the traditional telling, and would last for 300 years–it is, as they say, kind of a big deal.

And the rapid upheaval of the 600s did not end with the establishment of the new dynasty, with its imperial seat at the old Han dynasty capital of Chang’an (today, the city of Xi’an). For Emperor Gaozu of Tang built on the expansionism of the Sui dynasty, preferring to secure China’s frontiers not with imperial conquest but with diplomacy.

Now, you sometimes hear the Tang dynasty called “more diplomatic” than the Sui, and that’s…sort of true. Emperor Gaozu and his successors were not as reliant on pure military force to secure their new empire’s borders, instead relying on a combination of war and diplomacy. But it’s also unfair to characterize the Tang as pure Confucian pacifists who ruled with moral force and authority rather than an iron fist.

The policy of the dynasty in Korea serves as a good example here. Starting with the second Tang emperor Taizong, the Tang dynasty began to intervene in Korean politics just as the Sui before it had. However, this time the Chinese did not enter the region without allies–Tang Taizong worked out an alliance with one of the few female Korean rulers in history, Queen Seondeok of Silla; the subsequent Tang-Silla alliance was able to conquer much of the other two Korean kingdoms of Baekje and Goguryeo. By 663 CE, those two kingdoms had been wiped out. Baekje in particular had continued to receive military aid from the Yamato Kingdom down to the very end; at the final stand of Baekje in the late summer of 663 at Baekgang, thousands of Yamato troops were on hand to try and stave off the collapse of their longtime ally. That help, however, did not make a difference; Baekje was crushed and subsumed by Silla all the same.

In future generations, the Tang-Silla alliance would break down and result in a brief war between the two, but after Silla’s victory (unifying much of Korea under their rule in the process), the two governments would return to friendly relations. Much like the Tang, Silla would remain in place until the 900s CE.

Which, ok, we’re decently far into this episode so far and none of this has been about Japan–why does it matter? Well, simply because it radically remade the board, so to speak, on which the game of politics was being played.

If we return to that quotation from Dr. Pyle, part of his underlying logic for highlighting those three moments as major turning points in Japanese history was that they were all the results of pressure from outside powers. In the cases of the later Meiji Restoration and the US Occupation after WWII, that outside power was the United States (and more broadly, Western nation-states in general), whose economic, political, and military power forced Japanese leaders to consider changes that previously would not have been thinkable. And in the case of the Taika Reforms, part of the impetus for change was the new situation on the continent.

For pretty much all of the history of the Yamato Kingdom, China had been divided into comparatively weak warring kingdoms, none of which could seriously threaten Japan–and Korea had been similarly divided into warring states that were not only not a threat to Japan, but whose conflicts could be manipulated to the advantage of the Yamato kingdom.

Now, things were very different–now the continent was centralized enough to threaten Japan. And indeed, even if a military threat never emerged from the continent (which was not necessarily a foregone conclusion, though in the end the leaders of the Tang dynasty decided that a military expedition was not worth the potential costs) the power, splendor, and cultural dynamism of the Tang dynasty was hard to miss for those in power in Japan, eying the wealthy court of the Tang emperors with envy.

And of course, remember all the challenges the Yamato kingdom faced in the 500s which we talked about last week–the memory of those civil conflicts certainly factored into the envy with which Japanese rulers looked at the more centralized governments of the continent.

Of course, if you read period sources like the Nihon Shoki for their description of the Taika Reforms, none of this worry (or envy) in relation to the continent shows up at all. In those cases, the sources are pretty clear–what drove the Taika Reforms was concern over the domineering power of the Soga clan.

As we covered last week, over the course of the 500s and particularly after their defeat of their rivals in the Mononobe clan in 587 during a war over succession within the imperial line, the Soga clan became Japan’s pre-eminent family–in many ways, the puppetmasters of a line of emperors descended from or allied by marriage to Soga interests.

That level of Soga clan domination was, of course, not very popular with those who were not a part of the Soga clan, but challenging their rule militarily was not possible–the Soga were also very central to Japan’s trade with the continent, which had made their clan very wealthy (and militarily extremely powerful). By 645 CE, Soga no Iruka, the Sog clan omuraji, or chieftain, was one of the country’s most powerful men–arguably the most powerful, in fact.

Ultimately, what brought the Soga down was not battle but a clever bit of backstabbing, led by two of the leading figures at court–an imperial prince, Naka no Oe (the son of the then reigning empress Kyogoku and a previous emperor), and the omuraji, or clan chieftain, of the Nakatomi clan, Nakatomi no Kamatari.

Prince Naka no Oe’s involvement is easy enough to understand–as he himself would justify things at a later date, he was concerned that the imperial family to which he belonged was being sidelined to such a degree that the Soga clan would eventually supplant them altogether, and saw a sudden decapitating blow as the best way to defeat the Soga quickly and cleanly.

As for the Nakatomi, they’d been aligned against the Soga for quite a while now–the Nakatomi clans had been one of the ones to argue against the Soga-backed adoption of Buddhism in Japan more than a century earlier.

As a rival clan, it makes sense that the Nakatomi leadership would be concerned about the growing power of the Soga to dominate Japan’s politics.

Fortunately for them, they’d been on the sidelines in the Mononobe-Soga war, and thus escaped unscathed–but as a result also lacked the strength necessary to directly challenge Soga rule.

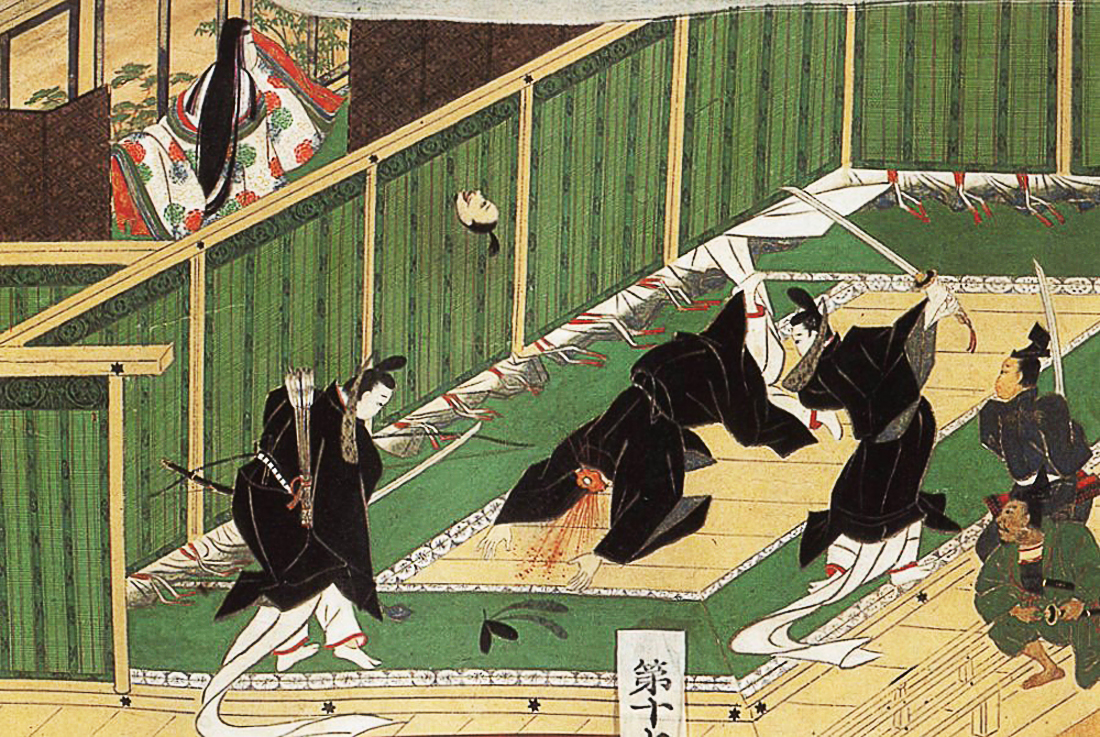

Instead, Prince Naka no Oe and the Nakatomi omuraji Kamatari cooked up a plan–on the 12th day of the 6th lunar month of 645 CE, ambassadors from Korea’s rival kingdoms were slated to make an appearance at court, at that point set up in a temporary location in Nara. On that date, Soga no Iruka would naturally be present given the importance of Korea to Japan’s foreign policy; the anti-Soga forces would take advantage to launch a coup.

They were able to win over one additional co-conspirator, a distant Soga relative whose daughter was married to Prince Naka no Oe, and who apparently felt that being in charge of a weaker Soga clan was worth more than being a minor member of a more powerful one.

And, as it happened, things came off more or less perfectly. I’ll turn here to the description of the Nihon Shoki: “Hereupon (Prince) Naka no Ohoye ordered the Guard of the Gates to fasten all the twelve gates at the same time, and to allow nobody to pass. Then he called together the Guards of the Gates to one place and promised them rewards. (Prince) Naka no Ohoye then took in his own hands a long spear and hid it at one side of the Hall. Nakatomi no Kamatari and his people, armed with bows and arrows, lent their aid. Soga no Katsumaro (that minor Soga relative) was sent to give two swords in a case to Komaro, Saheki no Muraji, and Amida, Katsuraki no Waka-inu-kahi no Muraji (two other conspirators), with the message, ” Up! up ! make haste to slay him.” Komaro and the other tried to send down their rice with water, but were so frightened that they brought it up again. Nakatomi no Kamako no Muraji chid and encouraged them. Kurayamada Maro no Omi feared lest the reading of the memorials should come to an end before Komaro and his companion arrived. His body was moist with streaming sweat, his voice was indistinct, and his hands shook. Kuratsukuri no Omi wondered at this, and inquired of him, saying:–“Why dost thou tremble?” Yamada Maro answered and said:–“It is being near the Empress that makes me afraid, so that unconsciously the perspiration pours from me.” Naka no Ohoye, seeing that Komaro and his companion, intimidated by Iruka’s prestige, were trying to shirk and did not come forward, cried out “Ya! ” and forthwith coming out with Komaro and his companion, fell upon Iruka without warning, and with a sword cut open his head and shoulder. Iruka started up in alarm, when Komaro with a turn of his hand flourished his sword and wounded him on the leg. Iruka rolled over to where the Empress sat, and bowing his head to the ground, said:–“She who occupies the hereditary Dignity is the Child of Heaven. I, Her servant, am conscious of no crime, and I beseech Her to deign to make examination into this.” The Empress was greatly shocked, and addressed Naka no Ohoye, saying:–“I know not what has been done. What is the meaning of this?” Naka no Ohoye prostrated himself on the earth, and made representation to Her Majesty, saying:–“[Soga no Iruka] wished to destroy utterly the Celestial House, and to subvert the Solar Dignity. Is Kuratsukuri to be substituted for the Celestial descendants?” The Empress at once got up, and went into the interior of the Palace. Komaro, Saheki no Muraji, and Amida, Waka-inu-kahi no Muraji, slew Iruka.”

Now obviously there’s quite a bit to unpack here; first, I do love the detail that two of the conspirators were so frightened they “brought their rice up again”, in other words nervous puking over having to assasinate someone.

To be fair, I imagine it is a pretty nerve-wracking thing to do, but man, it has to hurt to have that be a detail that is forever immortalized about you.

Also, I absolutely love the bit about the minor Soga relative whose job it is to read a petition to the throne to stall while everyone gets into place, and who is so nervous he’s sweating like crazy before passing things off by saying he’s just nervous to be around the imperial presence.

That’s a great excuse and I’m using it next time I’m nervous during a speech.

Probably a bit more important to note, of course, is that the coup was successfully carried off-Soga no Iruka was killed, and the remaining Soga clan leadership, when they realized what had happened and saw their allies abandoning them, locked themselves in the clan’s fortified manor and set it ablaze.

In the process, they destroyed several earlier existing works of history we alluded to in previous episodes–presumably the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki are at least in part based on surviving fragments of these earlier texts, but it’s impossible to know for sure.

Two days after the assassination, Empress Kyogoku resigned–initially in favor of Prince Naka no Oe, but he refused the throne on the advice of Nakatomi no Kamatari, who pointed out that it would make the coup look like a cynical seizure of power rather than a brave attempt to defend the imperial throne and suggested Kyogoku’s brother be elevated instead.

Naka no Oe would not take office for two more generations, until after the passing of this brother (Emperor Koutoku) as well as Empress Kyogoku (who returned to the throne afterwards for six years under the regnal name Saimei). It was only then that Naka no Oe–known also as Emperor Tenji–finally took on the imperial office.

And it was under this series of reigns–with Naka no Oe/Emperor Tenji and Nakatomi no Kamatari calling the shots from behind the scenes–that the so-called Taika Reforms took place.

The goal of the reforms was, essentially, to remake Japan’s government administration in order to centralize the government on continental lines–both to protect against the growing threat from the continent and to strengthen the power of the emperors themselves to protect against future attempts to strip their power.

Those reforms were not always successful, mind you–the policy of supporting a pro-Japanese ally in the Korean kingdom of Baekje did not pay dividends when said ally was crushed by Tang dynasty-backed Silla, for example–but in other ways they very much did.

The Taika Reforms were not a singular package of laws passed in the immediate aftermath of the anti-Soga coup, but rather a series of policy shifts that took place over the subsequent decades aimed at copying Chinese models. For example, on the lunar new year of 646, Emperor Kotoku announced a four article edict remaking the administrative system (at the urging of Nakatomi no Kamatari and Prince Oe/the future emperor Tenji).

That edict abolished old positions like the omuraji clan chieftains who held substantial power over their own domains, in favor of a system of provincial officials led by a provincial governor, appointed by the imperial throne–just as the system worked in China. Similarly, villages would be reorganized into more consistent units of 50 households with aldermen granted special privileges by the state in exchange for enforcing laws and ensuring taxes were collected–another innovation borrowed from the Chinese model.

Around the same time, the court announced a new system for timekeeping based on the system: the nengo. This literally means something like “era name”, and is based on a system that was in use in imperial China at the time. As initially conceived, every so often court diviners would choose a new era (with the first one being Taika, from which the Taika reforms take their name), with that year being Taika 1. The next year would be Taika 2, and so on until the era name stopped being auspicious.

Natural disasters could cause this, as did the death of the emperor–but there were other reasons one might want to move on from a given era name.

At that point, a new era would be designated, and the cycle would begin again.

This system was first introduced in 646, but was used only intermittently in the intervening decades. However, starting in the early 700s the nengo system became standard–it remains in use to this day, though during the 1800s it went through a big change we’ll talk about when we get to it.

In 668, meanwhile, Prince Oe (now on the throne as emperor Tenji) ordered the compilation of Japan’s first defined legal codes (the so-called Omi-ryou laws). Subsequent revisions to the administrative and legal code would continue over the next 100 years.

So in summary, this is more or less the narrative that I got of what’s called the Asuka period–named after the village of Asuka in southern Nara where the imperial court spent a good chunk of the 500s and 600s.

A combination of growing external threats from the continent and concern over Soga domination of the imperial court led first to the 645 CE coup and second to the reforms implemented by the coup’s victors–collectively, those pressures led to the Taika Reforms and the remaking of imperial government into a more centralized model.

It’s a tidy narrative, and certainly the internal logic works, but there are also a few ways in which it doesn’t quite fit. For example, the adoption of reforms proved a bit haphazard, taking place over the course of decades–which doesn’t exactly fit the notion that all of this is because of some perceived existential threat to the survival of the kingdom, does it?

Maybe the story is not quite as neat and tidy as all that.

Since the 1970s, there has been a growing body of research questioning this neat and tidy evaluation of the Asuka Period, and calling for a reframing of how we tie all these events together.

For example, while it’s easy to point to the post 645 reforms and call them a reaction to Soga domination, things become a bit more complicated when you look before 645 and realize that even at that point, reforms were being put into place to strengthen the central government.

It was under Soga clan rule that Prince Shotoku–who we mentioned last week, he was the one who rallied the troops during the Soga-Mononobe War–implemented Japan’s very first administrative code. His so-called 17 article constitution, crafted upon Shotoku’s return from a diplomatic mission to Sui Dynasty China, is not the most practical–it is more concerned with the philosophy of government than laying out clear rules and structures–but was a meaningful reform nonetheless. In particular, the incorporation of Confucian notions of merit as well as benevolent hierarchy–that inferiors should serve superiors, but that superiority is predicated on service to others–would prove very influential in terms of governing philosophy going forward.

It was also under the Soga that the very first attempts to rank Japan’s aristocrats–and to do so based on their merit as servants to the throne rather than by birth–was implemented in the early 600s. That ranking system would continue to evolve going forward and will be very important to us in the future, but it was the Soga who introduced it in the first place.

So perhaps it makes more sense to talk about a “long century of reform” from the cementing of Soga power in the 580s all the way to the early 700s, with government leaders from differing governing cliques sharing an overall concern of strengthening the power of the imperial state.

Those attempts to strengthen the power of the state were not always successful; in Emperor Tenji’s final years in the 660s, the state was wracked by one more succession dispute. Tenji had named his younger brother, the future Emperor Tenmu, as his heir, but eventually began to sideline him in favor of a younger son by a favored concubine–a pattern we’ll see repeat once or twice, by the way.

When Tenji finally died in 671, his son and brother fought a brief 10 month war over the succession, egged on by opposing factions within the court–with the Nakatomi clan of Tenji’s old ally Nakatomi no Kamatari supporting the brother, and remnants of the old Soga clan and other anti-Nakatomi families siding with the son.

So not that different from the Soga-Mononobe war of almost a century earlier.

Still, when the war ended–with the victory of the brother and his installation as Emperor Tenmu–the drive towards centralization resumed, and the pattern of reform picked back up. Civil wars of this type become less common going forward (at least for a time), and this too is arguably the result of the centralizing reforms of the 600s, which made it harder for rival clans to challenge the sitting ruler or heir.

Tenmu and his wife and successor, the future Empress Jito, were critical to this shift. It was in particular under Jito that three of the final crucial changes of the 600s were inaugurated.

First was the move away from…well, moving. Jito established the first semi-permanent capital in Japanese history built on a Chinese model at Fujiwarakyo–what’s now Kashihara in Nara prefecture.

In previous eras of the Yamato period, the location of the imperial capital and imperial court would rotate on a somewhat regular basis around the area of what’s now Kyoto, Osaka, and Nara.

There are many, many theories about why this was, from administrative (moving the court closer to so-called “trouble zones” to keep an eye on things) to family politics (rotating the court to please powerful clans by offering them the prestige of hosting the imperial throne) to defense (for example, during the early 600s the court moved from the seaside area of what’s now Osaka to the mountainous interior of Nara–was that as a precaution against a feared invasion by the Tang dynasty?)

It’s even been suggested this was part of a religious taboo; Shinto today retains strong taboos against decay and uncleanliness, so that for example shrines are regularly torn down and rebuilt on a semi-consistent schedule. Perhaps the constant relocation of the capital was a part of this as well, with the moves being timed based on certain omens?

Once again, nobody’s quite sure–the movement is treated as simply normal in the written record, and nobody ever gives an explanation for it, as it’s assumed any reader would already be familiar with why it’s happening. Which is, from a more meta perspective, one of the real challenges of being a historian working with primary sources (firsthand accounts, in other words); it’s challenging to understand them without a good grasp of the context, because authors making firsthand accounts have certain assumptions about what their readers may or may not know that you, a historian working much later, will not always share–or which you may not always be able to figure out.

But anyway; whatever the explanation for the rotation of the capital, starting during this time the rotations began to slow. They did not end altogether; Fujiwarakyo would not remain the final site of the imperial throne, and it would take another century or so for what became Kyoto to become the seat of the emperors. But Jito was the first to inaugurate this critical step towards a more settled (and larger) central government.

It’s pretty clear that this shift towards a more settled government was necessary to accommodate the growing governmental bureaucracy of the imperial state–after all, running an empire modeled after imperial China meant having a much larger government in general, and one that was correspondingly harder to shift around.

Jito was also the first to shift the language by which the emperor was addressed. Prior to her reign, the people we call the emperors of Japan were addressed by a variety of titles, the most common of which was probably oogimi, or “great king.” Jito was the one to formalize the use of tenno–heavenly sovereign, a term designed deliberately to evoke two of the most common terms used to refer to China’s emperor –tianzi, or son of heaven (which has that same character for ten in tenno) and huangdi, or emperor (where the huang is same as the nou in tennou).

That linguistic shift, which was retroactively applied to previous emperors in subsequent writings, was clearly intended to draw a symbolic equivalence between Japan and China’s rulers–and this will certainly not be the last time we see someone try to do that.

Finally, Tenmu and Jito were central to shifting the very image of the emperor and the throne. If you look, for example, at Prince Shotoku’s 17 article constitution from a century earlier, the justification for a ruler’s power given there is their superior morals–it’s a distinctly Confucian idea based on the Chinese notion of the mandate of heaven, where the ruler is legitimated by heaven because of their benevolence towards the people.

Tenmu and Jito began to emphasize a different model of emperorship, in line with their notion that they were not merely kings but “heavenly sovereigns”. Their proclamations are tinged with the language of divinity, referencing their divine descent from an “akitsukami”, or “shining deity”, in the form of Amaterasu.

It was under Jito in particular that the Kojiki, that first surviving written history, was first compiled–its genealogy of emperors descended from gods is a clear example of this desire to legitimate the throne itself as divine.

Of course, painting themselves as divine monarchs was clearly useful for two rulers trying to centralize their territories–but it will also have important effects down the line, particularly on the fate of the imperial house itself.

On balance our picture of the 600s, then, should be one of a move towards a more centralized Japan on the Chinese model. However we choose to interpret what drove those events–worries about the continent, concerns over the powerful clans, or anything else–the impact is very much clear. And next week, we’ll see that drive continue–culminating in the establishment of the permanent capital and the beginning of what we call Japan’s classical era.