In the first of a multi-part series on the history of communications technology in Japan, we’ve got a double-header: the landline telephone and telegraph. How did two technologies we now think of as ancient help remake a country opening itself up to the industrial world?

Featured image: A woman uses a public phone at a store in 1955. (Image source)

Sources

Partner, Simon. “Taming the Wilderness: The Lifestyle Improvement Movement in Rural Japan, 1925-1965.” Monumenta Nipponica 56, no. 4 (2001): 487–520. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096671.

Yang, Daqing. “Telecommunication and the Japanese Empire: A Preliminary Analysis of Telegraphic Traffic.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung 35, no. 1 (131) (2010): 66–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20762429.

Wells, S. William. “A journal of the Perry Expedition to Japan (1853-1854)”

Yukichi, Fukuzawa. “Conditions in the West.”

Images

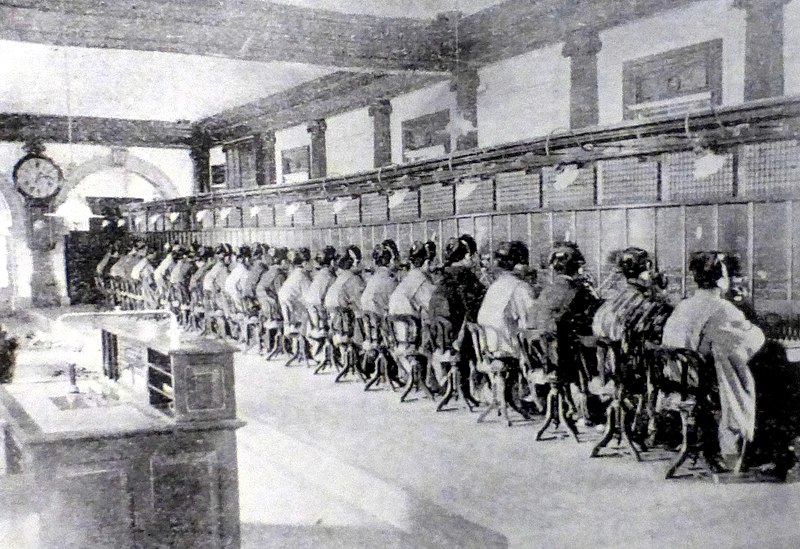

Telephone operators in Yaesu in 1902. (Image source)

The inside cover of Fukuzawa Yukichi’s “Conditions in the West,” showing telegraph wires around a globe. (Image source)

A telegraph stamp from 1895. (Image source)

An early telephone (on the right) and telephone exchange (on the left). (Image source)

A Telecom (wired telegraph machine) used by the Japanese army. (Image source)

A 1963 photograph of an NTT carrier delivering a telegram. (Image source)

Operators working at a KDD telephone exchange in the 1960s. (Image source)

Transcript

Japan’s forceful opening took place at a somewhat fateful time in the history of humanity. The collapse of feudalism and the emergence of a modern imperial nation-state occurred against the backdrop of 19th-century industrialization, which has of course fundamentally remade the way we as a species live thanks to the magic of industrial technology–and the perils it can create.

But of course, the industrial world isn’t just about factories–and for the next few weeks, I want to focus on one aspect of that shifting industrial world: the technology of communication. This is, of course, an incredibly important field–after all, technologies of communication are what’s making it possible for you to be listening to my voice anywhere in the world in your magic glowing rectangle. But even before the internet, these technologies were essential for binding ever more complex societies together.

And that, in turn, is a really important idea for us to think about. If you’ve ever taken, well, basically any course in political theory or modern history or anything like that, you’ve probably been exposed to the ideas of one Benedict Anderson–we’ve certainly talked about him before.

For a quick refresh, Anderson is most famous for his study of the history of modern nationalism, entitled Imagined Communities. Anderson’s basic thesis is all about the role technology–particularly, in his case, print media–plays in tying together people who realistically will never actually meet each other by allowing them to share a common narrative about their world.

If that sounds abstract, what Anderson is essentially saying is this: a person in New York and in Texas don’t necessarily have anything in common with each other, but if they’re both reading the same newspapers (or watching the same nightly news program, or reading the same news blogs) they’re getting the same stories about the world they live in and their role in it–and that creates a sense of kinship where there wasn’t one before.

The shared story provided by mass media, in other words, is what lets these two people believe they share a common community despite such geographical distances–and believing in the community in turn is what makes it real.

Anderson is focused very specifically on print journalism’s role in all this, but as Kerim Yasar points out in his excellent book Electrified Voices, print is not the only technology with a role to play in these developments. And over the next few weeks, I want to focus on a few of those technologies and the historical circumstances under which they came to Japan, and the ways in which they helped remake the country into what it is today.

Today, I want to start with two pieces of technology with tightly intertwined histories–one of which is now consigned largely to the dustbin of history, the other of which is (at least in the view of most millennials I know) headed there fast. I refer, of course, to the telegraph and the telephone.

Telegraphs, if you’re not familiar, relied on electrified wires to transmit signals back and forth–those signals could be converted into letters and symbols, and thus used to pass text rapidly across wide distances.

Honestly, the best comparison is probably to modern texting, except reliant on a wired connection instead of wireless transmission.

And the idea here is OLD; the first mention of it dates to February 17, 1753! On that date, an anonymous letter signed only “CM” was submitted to Scots’ Magazine (which is still in circulation, the world’s oldest still-circulating magazine, reporting as the name implies on matters of interest to Scottish people).

And intermixed in that issue with what I assume were a bunch of articles on treating whiskey hangovers and how to cook haggis (just kidding Scotland I love you) was this letter from the anonymous CM suggesting a very peculiar idea for a device. The device would have two terminals, and wires moving between them, with each wire labeled as a different letter of the alphabet (wire a, b, c, and so on). With enough wires for every letter (and presumably some punctuation and spaces), you could pass text back and forth instantaneously simply by spelling out your message and signaling the correct wires in order, using a friction generator to generate the electricity for the signal pulses.

It’s a neat idea, based on the already-extant field of optical telegraphy–using visual signals over long distances, for example using lanterns and signal fires.

That’s a technology with its own long history, stretching back thousands of years to classical antiquity.

From what we know, though, neither CM nor anyone else was able to build this newfangled machine, because generating enough electricity to send the pulses any meaningful distance was still an engineering challenge beyond what was doable.

It would take until the early 1800s for the technology to develop enough to make telegraphs feasible in any meaningful sense. First, in 1825 the British inventor William Sturgeon invented the electromagnet, the basis of much of modern communication technology. For our purposes, what’s useful about it is that electromagnets are far more reactive to electricity than traditional magnets–so the signal does not need to be as strong, increasing its effective range. Five years later, the American Joseph Henry cracked the distance issue–it turned out a series of batteries rather than one big one could send a signal reliably over a wire more than a mile long.

And then finally, in 1835 a professor of design and art at New York University by the name of Samuel Morse began to develop a device that sent electric pulses along a wire to deflect an electromagnet–the movements of that electromagnet in turn would emboss a series of dots and dashes onto a piece of paper. Morse then worked out a code that would translate those dots and dashes into letters and punctuation–creating the code that would take his name and remain in use (if Star Trek is to be believed) well into the 2300s.

Morse would continue to refine his system, to the point that in 1844 he was able to send a message over 44 miles (from Washington DC to Baltimore)–the message was “WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT”, if you’re wondering.

And it turned out, God had wrought a pretty good signaling system; 44 miles isn’t a huge distance, but it was enough to start setting up relay stations to keep passing messages along, making telegraphs seriously viable for rapid communication. Morse’s system wasn’t the first out of the gate, but it was the one that became the global standard. International treaties eventually spelled out the rules for an international Morse Code, and telegraphy was born.

By the 1850s, tens of thousands of miles of telegraph wires spanned Europe and the United States, though the technology remained rare in European and American overseas colonies. One of the devices brought to Japan in 1853 by Commodore Matthew C Perry was, in fact, a functional telegraph with three miles of wiring–the official record of the expedition recounts attempts to demonstrate it to the Japanese envoys sent to negotiate with Perry, though language barriers and the fact that most of the Americans did not have a good enough handle on electrical engineering to explain how it worked made the task rather challenging.

And this was not even the first functional telegraph in Japan–four years earlier, a rangakusha, or student of “Dutch” (that is to say Western) learning by the name of Sakuma Shozan had built his own functional model telegraph using diagrams from European books he’d acquired and translated.

Sakuma was an ardent follower of news from outside Japan, and had become convinced after China’s disastrous defeat in the First Opium War in 1842 that a similar fate awaited Japan if it did not begin to adapt modern technology to its own defense. For his troubles, he was assassinated in the 1860s by radical antiforeign samurai for being too pro-Western.

The telegraph remained something of a curiosity to most in Japan for the next few decades, however; the first Japanese national to learn how to use one was actually Enomoto Takeaki, the man who led the last holdout of the Tokugawa shogunate in Hokkaido and who would go on to direct that island’s colonization for the new government. Before all that went down he’d studied abroad in the Netherlands, and there learned how to operate one of the newfangled machines.

It was Fukuzawa Yukichi, the great intellectual of the early Meiji era, who really brought the idea of the telegraph into the public consciousness. His 1866 Seiyou jijou, or “Conditions in the West”, was one of the first popular works written to explain life outside of Japan to a Japanese audience. Written on the basis of notes Fukuzawa took from 1860-62 during missions to the United States and Europe, the book was also written in a style closer to vernacular Japanese, making it far more accessible to the average audience than most books on affairs in the West. The first printing sold 150,000 copies, a clear indication of wide-ranging interest in the subject–and the inside cover of that first edition depicted a globe crisscrossed by telegraph wires and steamships.

Fukuzawa clearly believed in what this new technology could do; he would later write that, “[w]hen we think about the function of the telegraph, we can either say that the distance of 1,700 // has been reduced to naught, or that the body of the Japanese has been extended to all locales. Since there are also telegraph lines in foreign countries, not only Japan but the entire world will be shrunk and made more manageable.”

Among those reading Fukuzawa’s description of the power of the telegraph were many of the leaders of the new Meiji state–by 1869, the government had already organized a line connecting the port of Yokohama to the national capital at Tokyo, and from there the network expanded rapidly.

An Osaka-Kobe line was completed in 1870, Tokyo to Nagasaki by 1873, Tokyo to Aomori in 1874, and Aomori to Hokkaido in 1875. If you’re familiar with Japanese geography, you’ll note that this means within 7 years of the start of the Meiji Era, the government had constructed telegraph lines connecting opposite ends of Japan–from here, the emphasis shifted to “backfill”, so to speak, connecting the major cities of the country to this existing “skeleton” network. This network also plugged Japan into the wider global telegraphic system–in 1871, the Danish Great Northern Telegraph Company completed lines connecting Nagasaki to both Vladivostok and Shanghai, and from there on to the rest of the world. That meant that once Nagasaki was connected to Tokyo in 1873, it was possible to send a telegram from Tokyo to somewhere as far away as London in about one day. By comparison, it’d generally take well over two months to send a letter that far.

Now, if you know the Japanese language, you’re probably already asking yourself an important question–how exactly do you render Japanese into telegraph form? After all, Japanese makes substantial use of kanji, the ideographic characters borrowed from Chinese. You need thousands of these just to be literate at a basic level in Japanese–but that doesn’t work with Morse-style code, because you would have to memorize thousands of dot-dash combinations to be able to transmit characters over a telegraph wire.

Indeed, this exact issue had already cropped up in China; when the Chinese imperial government began setting up its first telegraph lines in 1880, there was no standardized system of Chinese Romanization–a way to write Chinese phonetically using Roman letters. The oldest system in use, Wade-Giles romanization, wasn’t put into place until 1892! So instead, each character was assigned a numerical value that could then be transmitted via Morse code, and then converted back from numbers into characters–a highly inefficient system because you had to “encode” and “decode” each message twice, first from characters to numbers and then from numbers to Morse code. This made telegraphs both much slower in China than anywhere else and far more expensive.

In Japan, however, this problem was dodged thanks to the very first thing you learn as a first year Japanese student. You see, unlike Chinese, Japanese does have phonetic characters–the language is written using a combination of kanji and phonetic hiragana and katakana characters. Telegraph messages were simply written entirely phonetically using these kana syllables–this can be confusing given the number of homophones, or different words with the same pronunciation, that Japanese has, but for basic messages it was perfectly manageable.

However, for the first decade and a half of the telegraph’s existence in Japan, the technology was extremely limited in use. Only government and military officials were allowed to make use of the telegraph network–for example, the Kyushu branch of the telegraph network proved essential to coordinating responses to the Saga and Satsuma rebellions of discontented samurai in the 1870s. The earliest telegraph stations were actually set up in areas the Meiji Emperor visited in his early tours of the country, presumably as a way of ensuring the emperor remained connected to goings on in the capital.

It wasn’t until 1885 that a revised Telegraph Law promulgated by the Meiji leadership allowed for civilian use of the telegraph network by means of a government-run network managed by the Teishinshou, or Communications Ministry, and then only at hideously expensive rates. A message of twenty or fewer syllables was 7 sen to send, with a surcharge of between 2-5 sen for each station the message had to be relayed through. This at a time where the average household income was a bit less than 200 yen per year–outside of wealthy businessmen, very few bothered to send messages via telegram, preferring the far cheaper if slower postal service.

It was not until the early 20th century that telegraph access became consistently affordable for average people in Japan–but when it did, it kickstarted a process that we’re going to see pretty consistently across all the communication technology we’re going to be talking about–the standardization of the Japanese language.

As anyone who has ever spent time in the more rural parts of Japan can tell you, local dialects are still very much a thing in the Japanese language, but they used to be quite a bit stronger and more prevalent. However, one of the things that a nationwide communications network requires is some standardization of language–it doesn’t matter if you can send a message from Aomori to Tokyo in a matter of minutes if that message is in an Aomori dialect nobody in Tokyo can understand.

This meant, of course, that some standardization of language was necessary–the Meiji government, never one to leave these things to chance, decreed that “standard” Japanese would be based on Tokyo dialect. This was far from unusual; standard Chinese is based on Beijing dialect, standard French is Parisian, and so on.

The telegraph system was one of the ways this standardization was enforced–and given its limited scope at this time, not the most effective one compared to, say, a school system that only operated in standard Japanese. Other forms of communication would drive this standardization forward, but the process starts with telegraphy–so I wanted to note it here.

Speaking of other technologies, there’s one other one I wanted to introduce today. It’s a bit harder to say who is responsible for it, because the question of credit for inventing this particular piece of technology was almost immediately wrapped up in countless lawsuits and countersuits and patent battles. But honestly, that’s all beside the point–what really matters for us is that the telephone was a pretty revolutionary piece of technology.

Telephones work, of course, by transmitting sound over wires using electrical current. Older mechanical or acoustic designs existed as far back as the 7th century CE in Peru–these all operated more or less on the same principle as a ‘tin can phone’ that you can make by connecting two cups with a taught string.

Those devices, however, have pretty limited range; electric telephones are far more efficient at transmitting sound over distances. Simply put, these work by using a receiver to convert sound waves into electric pulses of varying strength, which are then transmitted down a wire and “decoded” by a speaker on the other end.

And as I already hinted at, it’s hard to say who actually invented this first; credit for the invention is disputed between the Scottish-born Alexander Graham Bell, the American-born inventor Elisha Grey, and the Italian-American Antonio Meucci. Unless, of course, you’re my high school Italian teacher, in which case it was obviously Meucci and the whole thing is an elaborate conspiracy to defame the people of Italy and deprive them of credit for one of their glorious accomplishments. For our purposes, it doesn’t really matter except to say that by the mid-1870s, a few different prototypes of electric telephones were floating around.

And it didn’t take very long for those prototypes to make their way to Japan; the first domestically produced Japanese phone was manufactured in 1878 by the Koubushou, or Ministry of Industry. One of the first testers of the device is reported to have said, “Oh, it’s just like hearing the voice of a ghost!”

However, despite that impressive (if spooky) endorsement, phones were not quick to catch on in Japan; the first proper phone line in the country (between Tokyo and Atsumi) was not constructed until 1890, meaning that Japan was actually a late entrant to the telephone game–behind countries like Thailand, Romania, and Chile.

There’s no clearly articulated reason why it took the Meiji government a while to invest in this new, seemingly obviously useful piece of tech, but we do have a few good guesses. For one thing, the sound quality of the earliest telephones was awful–it took a few years to really get them to a properly usable state. For another, the telegraph network had a baked-in “advantage”–it was already well on its way to being set up by the time phones were introduced to Japan, and despite their novelty phones didn’t really offer that much more actual utility at first. Police and government-backed businesses made use of it, but that was about it–at least at first.

Still, by 1890 the technology had advanced enough that the Ministry of Industry decided to set up the first public phone network in Japan for the city of Tokyo. And the results of this new and bold step into the future were…absolutely abysmal.

Only 74 people signed up! And when the government tried to boost numbers with a PR campaign that reached out to over 800 journalists, celebrities, and other public figures, only 23 more people decided to embrace this revolutionary new technology.

Of course, there is some context for those low numbers; at the time, Tokyo was in the middle of a cholera epidemic, and as a result, people were somewhat reticent to let strangers into their home to install these new devices–plus, a rumor was flying around the city that telephone wires could transmit the deadly disease.

Still, before long interest in the new device did begin to pick up. In 1893, an Osaka to Kobe phone line was set up, and by 1898 an Osaka-Tokyo line had been established. By 1902, there were 42 telephone exchanges around the country, and over 35,000 people had subscribed to the phone system–though in a country of around 46 million people, that did represent only about .076% of the population.

One imagines that for those that did have it, the telephone was a symbol of novelty, innovation, and the technological cutting edge. Still, even in these early days you can see complaints about the other thing phones would come to represent: a constant source of distraction. The Meiji period writer Natsume Soseki wrote of his phone, “I bought a phone because I needed it to make calls, but I have no use for the calls that are made to me.”

One of his disciples, Uchida Hyakken, would later recall that Soseki wrapped his phone in gauze to prevent the ringer from making noise, as he found it distracting whenever someone tried to call him while he was working. “When he first got it, he just left the receiver off the hook, but the people at the telephone exchange made a big stink about that, so he simply rigged the phone not to ring even when somebody called.”

Still, that was only the percentage of the population with a phone in their home; if you’re younger than a certain age you may not realize this, but once upon a time public phones were very much a thing. Phone booths were still a ways away, but public phone offices where anyone could make a call were a fixture of many cities by the late 1890s. The costs were high, but not necessarily prohibitive; a call within Tokyo cost 5 sen, and one to nearby Yokohama 15 sen–that’d be around 600 yen today, if I’m doing my conversion math right, so not cheap but far from unaffordable. And things only got more affordable with the introduction of actual public phone booths in 1901; originally these were called jido denwa, or automatic phones, because you didn’t have to deal with an attendant to use one, just put the requisite fee directly into the coin slot.

There was even a highly complicated system of yobidashi denwa, or “telephone summons”, for two people who wanted to talk without either of them owning phones. The system, set up by the Communications Minsitry, in 1900, required an interested party to go to the telephone office to ask for a call. The clerk there would then call the exchange office for the phone system, which would connect to the office nearest whoever the intended recipient was. That office could then issue a yobidashi tsuuwaken (telephone summons ticket), which was delivered to the intended recipient’s home. That ticket was valid for several days–sometimes, they came with a set appointment time for the call, but for others you’d simply have to show up at your office and wait until the other office summoned the person who tried to call you in the first place.

The whole system was monstrously complicated and time consuming, particularly compared to just sending a telegram–but the novelty of actually getting to talk to people was such that it saw serious use. 6,600 such calls were placed in the first year the system was available, and by 1935 that number rose to 2.26 million.

As those numbers might suggest, telephone calls were rapidly growing in popularity during the early decades of the 20th century; indeed, the main thing slowing down the pace of adoption of home phones by the later decades of imperial Japan was not interest, but infrastructure. The construction of new telephone exchanges–where operators would route calls between two numbers–simply could not keep pace with the number of interested callers. As one newspaper editorial from 1918 put it: “Recently, telephone exchange service has become particularly unacceptable. A call that, as a general rule, should take eight seconds to go through can take ten minutes, even twenty, from the time one rings the operator. A call that takes only 20 to 30 seconds to go through is on the fast side.”

The numbers back this up; by the 3rd decade of the 20th century, an operator–more often than not a young woman between the age of 14-25–would be expected to handle between 270-280 call routings in an hour.

If you’re unsure what I mean by “routing a call” because you’ve never seen an old-style switchboard: basically, whenever you placed a call under this system, you’d have to talk to an operator, and give them the number you were trying to reach. They’d then manually connect a wire between your line and the line you were calling–these manual exchanges have of course since been replaced by automatic, electronic ones, but back in the day this was how all calls were routed.

These operators, by the way, are generally the ones credited with introducing the standard response when answering a phone call: moushi moushi. Now, so far as I know nobody actually knows for sure where this phrase originated from. The commonly accepted conjecture is that it’s derived from mousu, the humble form of “to speak”–meaning that the operator is prompting whoever called to speak and tell them who to connect to.

Experienced operators, meanwhile, were sometimes asked to handle as many as 350 calls an hour during peak hours. The writer Tanizaki Junichiro once sardonically remarked of the system that, “calling from Yokohama to Tokyo took half a day, long enough to go to Tokyo and come back. Actually, it really was faster just to go to Tokyo and come back.”

And all this reveals something interesting about the history of technology in Japan–and really just in general. Even today, the rhetoric we hear about technology is all about convenience; it’s going to save us time, and make our lives more efficient, and all that jazz.

But this system wasn’t efficient at all! For the first few decades of its existence in Japan, the telephone system was just plain outclassed by telegrams, and even by snail mail–in Tokyo, the mail was delivered 10 times a day, meaning that letters could realistically cross the city within just a few hours and faster than a phone call could be routed through the exchange system.

And that wasn’t even accounting for the fact that most people didn’t even have access to telephones; the system was not brought to rural areas until the 1950s, when the postwar government came under pressure to extend modern technological infrastructure into the countryside in order to win rural votes. This despite the fact that until the middle of the 20th century, Japan’s population was primarily rural, not urban.

And yet, people flocked to use this technology–literally to the point of creating a bottleneck in the exchange system. And that, I think, raises a very interesting question. Do we really adopt new technology because it’s efficient and useful and produces genuine value? Or is there just something about newness–about the cutting edge–that’s exciting, even if getting the cutting edge to actually, you know, work is kind of a massive pain? Maybe we just like things that are shiny and new and let us do cool things like talk to someone far away from us instantaneously–even if, practically speaking, getting the damn thing to actually work consistently can be a bit of a pain.

Now, I don’t want to end this episode without noting one other aspect of the telegram and telephone network in Japan. Both were government monopolies before the end of World War II, managed directly by the state bureaucracy (specifically the Communications Ministry). Actually, fun fact: During the US occupation of Japan, the American company AT&T managed Japan’s telecom network; it wasn’t until 1952 that said network was spun off into a state-owned corporation, NTT (Nippon Telegram and Telegraph).

Anywho, the fact that the telecommunications network was a direct part of the state bureaucracy meant that it was linked to the goals of the state itself, including the construction of an overseas empire. In all of its colonies, Japan’s government set up telegram stations to connect back to Tokyo–telephones were a bit rarer simply because of the extra complexity and expense, but all of Japan’s colonial outposts had at least some telephone exchanges.

The modern scholar Daqing Yang has actually done some fascinating statistical work on prewar Japan’s telecom system and the empire, which demonstrates well the extent to which those technologies were a big part of securing Japan’s imperial ambitions. Korea, for example, had about 31% of the population of Japan proper in 1935–but only 10% of the number of telegraph offices and 4% of the number of telephone subscriptions–a marker of both the poverty of the colony relative to the mainland and a comparative lack of interest on the part of the government-run communications utilities in ensuring access among colonial subjects. That pattern is pretty consistent, as well; you see the same thing in other longstanding colonies like Taiwan (7% of Japan’s population, 2% of the number of telegraph offices and telephone subscriptions).

Yang also found data from two colonial subsidiaries of the imperial telecommunications network (Manchuria Telegraph and Telephone and North China Telegraph and Telephone) demonstrating the extent to which use of the network was dominated by Japanese rather than local residents. For example, a one-day survey of private (so non-government) telegraph traffic in 1939 found that 80% of telegrams were sent by Japanese nationals–who were less than 5% of the overall population.

The numbers are not quite as extreme in North China, which never had the same size of Japanese settler population as Manchuria–a three day survey by NCTT in 1940 found that 58.4% of telegrams sent and 57 percent of telegrams received were in Japanese. But those skewed numbers are still indicative of a system of privileged access for Japanese residents, who were generally far better off in the colonies than the natives.

These disparities were even reflected in things like news dispatches on the telegraph system–which vastly privileged information coming from Japan to the colonies rather than the other way around. In 1933, 1050 press telegrams were sent from Japan to Korea; 1100 to Taiwan, and over 1200 to the Japanese colonies in southern Sakhalin–by comparison, press reports going the other way, from colony to colonial power, were extremely scarce. Sakhalin had the most, at 600–presumably because its proximity to the Soviet Union made developments there of particular concern. Korea had only 400, and Taiwan 100.

All told, the picture that emerges is fairly clear–the telecommunications network existed primarily for the benefit of Japan’s colonial ambitions, with little to no thought being given to how it served (or did not) the non-Japanese population. Which, broadly, tracks with the history of communication in general–as we discussed at the beginning of the episode, communications technologies are interesting and important because of the extent to which they can serve as vehicles of state control and power. Advances in telecommunications have made it easier than our ancestors could ever have imagined for us to talk to each other–but ease of communication is not always a good thing. It depends, in the end, on what’s being said.