This week: the Pal dissent becomes the Pal myth. How did an obscure document from the Tokyo Trials end up front and center in nationalist discourse in Japan today?

Sources

Nakazato, Nariaki. Neonationalist Mythology in Postwar Japan: Pal’s Dissenting Judgment at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Nandy, Ashis. “The Other Within: The Strange Case of Radhabinod Pal’s Judgment on Culpability.” New Literary History 23, No 1 (Winter, 1992).

Ushimura, Kei. “Pal’s ‘Dissenting Judgment’ Reconsidered: Some notes on Postwar Japan’s Responses to the Opinion.” Japan Review 19 (2007).

Images

Transcript

As we covered last week, Radhabinod Pal’s dissent at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials–more formally, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East–was a product of many different contemporary factors: his Pan-Asianism, his right-wing Indian nationalism, his personal relationship to men like Subhas Chandra Bose, and his personal antipathy for British colonialism, and by extension for the larger Western apparatus of power in Asia.

In that sense, it’s a historically fascinating text–but the thing is, when it first saw daylight in December, 1948, it didn’t really make a splash at all.

The chief justice of the tribunal, the Australian William Webb, had at first attempted to head off the issue of dissents–judgments independent of the majority–by getting the justices to swear secrecy on their actual votes and to not publish any opinion but the majority one. Pal, however, refused to be held to that standard (in part because he arrived too late for the start of the trial and missed Webb’s discussion on the topic, but I suspect he never would have agreed to give up the right to publish his own views anyway).

Webb had wanted to avoid dissents for fear that visible disagreements among the judges would undermine the legitimacy of the tribunal–once this option was off the table, he decided to head off the issue by simply having every judgment (the majority, Pal’s opinion, and four other independent opinions drafted by other judges) read aloud at the conclusion of the trial. Webb hoped that in doing so, he could head off any potential accusations of secretiveness on the part of the judges that would undercut the legitimacy of the trial itself–and thus diffuse any criticism.

And the hell of it is, this worked–at first. It did take a WHILE; reading out all of the opinions took from December 4th to 12th, 1948. Pal’s dissent did get some press coverage on its own, but largely in India–the major dailies in his hometown in Calcutta covered it extensively, but more as a “look at this high profile Calcuttan” thing than because of the actual contents.

Indeed, the only real reaction the dissent got was from the Indian government–Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was incensed with Pal, who remember had ended up on the tribunal because of clerical issues caused by the British before India’s independence. He tried to pressure Pal to change his verdict and go with the majority, for fear that Pal’s opinion would damage India’s standing among the victorious Allied powers.

Nehru went so far as to prepare a joint communique with the British government disavowing Pal’s judgment–though in the end, it got so little coverage that this proved unnecessary.

By 1948, much of the public had moved on from discussion of the war years. The Nazi tribunal at Nuremberg had always been the more high-profile subject anyway, and once it concluded in 1946 there was a lot less interest in rehashing the issue at Tokyo. Indeed, partially for that reason, plans for more tribunals to follow the first in Tokyo were quietly scrapped–prosecuting even more of the leadership was simply too arduous a task. This is also why the records of the Tokyo Tribunal, unlike the Nuremberg one, were not officially published after the fact–the records were still accessible in archives, but it was assumed there wouldn’t be enough interest to warrant publication.

Pal himself found this out the hard way; he sent copies of his monstrous 1200 page dissent to several legal journals hoping to get it published, but it was rejected from all of them. When he finally arranged for the dissent to be published in India in 1953, only two journals bothered even reviewing it.

What this meant in practice was that Pal’s judgment did not get much airtime. Newspapers in China, both Koreas, and of course in Japan made reference to the dissent, but only briefly–Chinese and Korean headlines were more preoccupied with the wars and civil unrest in both territories, and in Japan newspapers were afraid that open criticism of the tribunal would result in their being censored by the Occupation government–which still maintained the legal right to shut down any discussions it deemed to be critiquing the occupation’s goals.

However, despite this tepid initial reception, the dissent obviously picked up steam over the years–because while the initial global situation was not favorable to Pal’s opinion, things were, of course, changing.

Partially this was due to changing circumstances in Japan, where after the initial round of war crimes tribunals Pal himself had judged the whole idea was scrapped–and hundreds of other indicted war criminals were unceremoniously released without trial.

Those releases were a part of the reverse course of the Occupation–starting in 1947-48, American Occupation leaders quietly abandoned their initial goals of democratization, demilitarization, and reform of Japanese society in favor of building Japan up as a US-aligned Cold War ally against the Soviet Union.

This reverse course involved rehabilitating huge numbers of bureaucratic, political, and military leaders who had been purged from office by the Americans because of their militaristic pasts. These leaders, in turn, had a vested interest in trying to ‘protect’, so to speak, some memory of the war years–since, after all, the war had been a project many of them were intimately involved in. And it’s here we find the beginnings of Japanese nationalist ‘revisionism’ around the War Crimes Trials–attempts to challenge the findings of the tribunal from the perspective of Japanese nationalism. Here too, we find the beginnings of what Nakazato Nariaki calls the “Pal myth.”

From what Nakazato found, the Pal myth emerged from the ashes of a pre-World War II group called the Greater Asian Society, or Dai-Ajia Kyoukai, a political organization founded in 1931 to propagandize in favor of Japan’s ‘special mission’ to liberate Asia. The group had several powerful connections among the elite of society at the time; Konoe Fumimaro, an aristocrat from an ancient family and twice Prime Minister during the lead up to World War II, was its titular head, and among its leaders was General Matsui Iwane–the Imperial Japanese Army’s foremost expert on China policy.

Today, of course, Matsui is best known as the commander of Japan’s Central China Area Expeditionary Army, the military force that perpetuated the Nanjing Massacre. And for his command of that force, Matsui was among the defendants at Tokyo, and was among the seven sentenced to death.

Two of Matsui’s former colleagues in the Greater Asian Society testified on his behalf at the trial as character witnesses: the publisher Shimonaka Yasaburo, who was also a politician in the wartime state political party the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, and the law professor Nakatani Takeyo. Both, in turn, attended Matsui’s funeral after his execution, alongside another Greater Asian Society alumn, the bureaucrat Kishi Nobusuke (who had been indicted for war crimes, but released without trial after subsequent trials were cancelled). Kishi, of course, would bounce back from almost going to prison, and end up an early founder and leader of the Liberal Democratic Party which came to dominate Japanese politics after the war years.

Nakatani and Shimonaka, having attended the tribunal as witnesses, were familiar with Pal in that context. Both were also friendly with another former Greater Asia Society member, Tanaka Masaaki, who was the first to publish Pal’s dissent in Japanese.

Well, maybe I shouldn’t frame it that way. Tanaka had begun to plan a publication of the dissent as far back as late December, 1948, when the members of the Greater Asia Society held a memorial service for Matsui Iwane after his execution for war crimes on December 23, 1948. Both Nakatani and Shimonaka attended the memorial, as did several of the defense lawers from the Tribunal. Tanaka heard about Pal’s dissent from them, and decided to translate and publish it–but also edited it substantially, and waited to publish it until the end of the Occupation in April, 1952 (for fear of the publication being censored by the United States).

Tanaka actually made these edits even though, when he contacted Pal about the publication rights, Pal requested that it be published unedited. Tanaka cut about 2/3rds of the text and added his own foreword–in which he held forth on several political issues of the time, most notably the importance of revision of the ‘peace constitution’ and Article 9, which banned Japan from having a ‘normal military.’

He also told Pal the title in Japanese would be The Bible of Peace, but actually published the text under the title Japan is Innocent–and broke a separate promise to Pal that the profits from sales would be distributed to the victims of the atomic bomb. Given that the text sold pretty well, this was not an insubstantial promise to break!

So far as I know, Pal never found out about this latter issue with royalties. He did find out about the title change, and was initially quite alarmed by it–noting, in classic lawyerly fashion, that his dissent had nothing to say about the guilt or innocence of Japan, since it had been specific leaders (not the nation as a whole) on trial. Eventually, however, he dropped the objections–indeed, an official biography of his life produced by his family in his final days states that Pal believed, “Japan was completely innocent.”

One might wonder why Pal vacillated in this way–after all, Tanaka’s title alone represents a pretty attempt to frame the issue as “Japan did nothing wrong”, which was something Pal tried to dance around himself in his judgment, drawing a line between legal and moral responsibility. Nakazato Nariaki offers one interpretation, “[Pal’s] judgment had a political character in that, although carefully worded, there was a marked tendency toward justifying the “Greater East Asia War” waged by Japan. Viewed from this perspective, Tanaka and Shimonaka were not necessarily wrong to take Pal’s opinion as an “argument for Japan’s innocence,” and when they actual- ly suggested to him that his judgment could be read in that way, Pal probably could not dismiss their views lightly. He appears to have wavered between his public stance as a judge and his true personal feelings. In this sense, it would not be off the mark to conclude that Pal himself shared at least part of the responsibility for the creation of the “Pal myth” in Japan.”

Nakazato also notes that for a brief time in the 1950s, Pal attempted to make a ‘lateral move’, so to speak, into Indian politics–specifically as a candidate within the ruling Indian National Congress Party. As a result, Pal tried to moderate his views for a time, specifically trying to avoid anything that might be seen as an endorsement of Japan’s rearmament (because the INC was very firmly a pro-disarmament party)–he would swiftly abandon that vaccilation, and seemingly endorse the right-wing Japanese nationalist interpretation of his dissent, once that bid fell out.

You can see this pretty clearly during Pal’s second visit ever to Japan, arranged by Shimonaka Yasaburo in October, 1952 to celebrate Tanaka’s translation of Pal’s dissent. Shimonaka himself likely viewed this visit extremely opportunistically; he, like quite a few other former Greater Asia Society Pan-Asianists before the war, would attempt an ideological conversion towards pacifism, rebranding his Pan-Asianism under the guise of pacifistic unity rather than militaristic expansion. The cynical interpretation of this was that Shimonaka and his fellow ideologues hoped to both smooth their reintegration into postwar society by shedding their associations with militarism, and to use Pal to attempt to launder the image of what they had participated in during the war years.

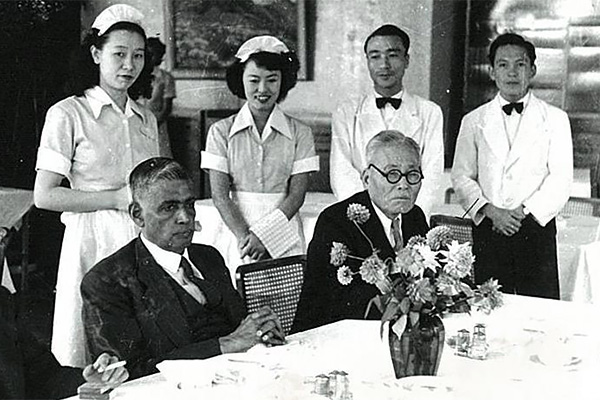

Pal agreed to the visit–probably hoping the visit would boost his political profile in India, given his rising political star. He spent 27 days in Japan, where he was treated as something of a celebrity–followed by the press and received by a “Committee to Welcome Judge Pal” set up by Shimonaka that included everyone from politicians to the upper strata of corporate leadership to religious leaders.

Pal’s his agreement to the itinerary–set up by Shimonaka–reveals the interesting political ambivalence of both men around the legacy of the war years.

On the one hand, Pal visited the atomic bomb peace park in Hiroshima and left flowers for the victims. He also gave a lecture at the University of Tokyo where he advocated against one of the common positions of the Japanese right in the 1950s–that the country should rearm its military and revise the constitution to remove the Peace Clause of Article 9. Instead, he said, Japan should follow a position of neutrality in the Cold War and a devotion to negotiated peace–the position, in other words, endorsed by the Indian National Congress, which made India one of the leaders of the non-aligned movement in the Cold War.

On the other, Pal met with the widows of all seven of the executed defendants from the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunals, and visited Yasukuni Shrine–already, in the 1950s, a center of the resurgent Japanese right-wing.

After this visit, public interest in Pal began to wane. The early 1950s was a time when resurgent Japanese nationalism was very much in the air; with the restrictions of the Occupation gone, for a time there was a massive boom in ‘revisionist’ discussion of the war years, with books like Tanaka’s edited version of Pal’s dissent flying off the shelves. However, while there were some Japanese nationalists who were very invested in this discourse, for many the overwhelming image of the wartime government and military was negative. And indeed, there were also a great many who simply did not care–who wanted to put the war behind them and focus on rebuilding the country.

In this atmosphere, for a time, interest in Pal’s judgment fell off; a second visit, in 1953, saw a lot less interest and enthusiasm, and after that point Pal stopped visiting the country regularly. He remained close to Shimonaka, but did not come back until 1966.

In the meantime, Pal actually fell on hard times personally; while he was quite prominent in the legal world in Calcutta, his bid for national politics failed, and at the same time he was embroiled in a tax scandal that sapped much of his hard earned wealth as a member of India’s emergent upper class.

But interest in the “Pal myth” had not totally dissipated. The 1950s was of course the era that really saw the reconstruction of the extreme right in Japan, the so-called uyoku dantai. These are ultrarightwing nationalist political associations, the most famous of which is the Aikokuto, or patriotic party, of Akao Bin, the man who called himself “Japan’s Hitler.” It was also one of his followers, Yamaguchi Otoya, who assassinated the socialist politician Asanuma Inejiro on live broadcast in 1960, if you remember our discussions of that.

Obviously, such people would have a strong stake in revisionism around the war years, because their nationalistic version of history was entirely premised on the idea that Japan did nothing wrong during the war years. Pal’s judgment–particularly because, being from India, he was both Asian himself and ‘neutral’ in historical conversations, having no stake in, say, Korea-Japan historical disputes–was a valuable tool with which to bludgeon opposition to that nationalistic reading.

Of course, strong is relative here, since again Pal himself morally condemns Japan’s actions in his dissent–and as we saw last week, the ways in which he deals with ‘historical disputes’ is questionable at best because there’s no real dispute to the legitimacy of things like the Nanjing Massacre.

More prominently, importantly, and arguably disturbingly, Pal’s dissent was also a valuable tool for many of those in positions of political power. Recall that early in the US occupation of Japan, the stated American goals of democratization and demilitarization of Japanese society meant wide-ranging arrests from the political, military, and economic leadership.

And I do mean a lot of people; over 5000 people were accused of class A and B war crimes, and I couldn’t even find numbers on class C ones (the most conventional of the three). And in addition, over 20,000 people were purged by the Americans and banned from politics because of involvement in the war effort.

The eventual reverse course–the walkback of ambitious restructuring of Japanese society in favor of stabilizing the country as a Cold War ally–meant that a lot of those indicted war criminals ended up going free without a trial, and most of the purges were walked back. Even some who were convicted and imprisoned were then later released by the Japanese government.

The political world in particular was eventually inundated with the depurged and with indicted war criminals–the most infamous, of course, was Kishi Nobusuke, who went from a cell in Sugamo Prison awaiting a trial to helping to found the titanic conservative party that is the Liberal Democratic Party and serving as its Prime Minister for four years.

He was far from alone, however. And even before him, the governmental leadership in Japan was not exactly firm in its condemnation of war criminals. For example, even before the end of the occupation the Yoshida Shigeru government put out a statement that it would not treat those convicted of war crimes as traditional criminals because they had not been convicted under Japanese law–thus, they would not lose their voting rights or military pensions, for example. Similarly, the government listed the cause of death for the seven executed defendants of the Tokyo War Crimes trials not as keishi–the death penalty, what’s normally done in this case. Instead, it was houmushi–roughly, ‘death due to judicial proceedings”–a phrasing intended to undercut the legitimacy of the judgment (and which, interestingly, opened the way to the eventual enshrinement of said war criminals at Yasukuni Shrine, which normally does not enshrine anyone convicted of a crime).

Government leaders thus had a vested interest in calling into question the legitimacy of war crimes trials, indictments, convictions, and even the purges–after all, many of them had been affected by these things, and worried about their own legacies and careers being tarnished.

Thus, for example, if you wander into a Japanese bookstore today and try to find a copy of Pal’s dissent, the one you’ll likely find was published in the 1960s by the Tokyo War Crimes Trials Research Group (the older versions have largely gone out of print). That name sounds neutral enough–but that ‘research group’ was actually set up in the 1960s by justice minister Kaya Okinori, himself a purged and convicted war criminal who was pardoned by the Japanese government in 1955 and returned to politics afterwards. The group included close associates of Kaya’s, whom he directed to essentially cast as much doubt as possible onto the legitimacy of the trial itself. This was, in fact, the whole reason that complete edition–which has more or less been reprinted yearly since it came out, was published.

Pal’s dissent also began to play well in an age of resurgent Japanese nationalism. Obviously in the immediate postwar era, the ruin brought by the war did not endear the government or the wider concept of nationalism to many–it was hard to argue for the greatness of Japan when most of Japan was in ruins. But as the memory of the war began to fade–and particularly in the 1960s, when the postwar economic miracle got going and Japan’s wealth was growing by leaps and bounds–a resurgent postwar nationalism grew alongside.

This, of course, reached its apogee in the 1980s, when Japan became the world’s second largest economy–economic growth leading to renewed nationalistic pride and confidence, which in turn led to things like the ever popular Nihonjinron–the nonfiction subgenre of self-congratulatory works about the origins of Japanese ‘uniqueness’ and greatness.

This whole atmosphere of nationalism in turn led to a resurgence of what might be called ‘imperial consciousness’–for example, you might be shocked to know that one of Japan’s most nationalistic holidays (at least in intent) dates not from the imperial era but from 1966. This is, of course, national foundation day, or Kenkoku Kinen no Hi, held every February 11th–supposedly the anniversary of the foundation of the Japanese state by the first emperor Jimmu back in 660 BCE.

This is, in other words, a day that commemorates the creation of Japan as a nation–tied up explicitly, in this version, with the imperial house–and which explicitly celebrates that linkage in a way very much reminiscent of imperial propaganda (it will be remembered, for example, that the prewar government planned a massive celebration of the ‘2600-year anniversary of Japan’s founding for February 11, 1940, and that the imperial constitution of 1889 was promulgated on February 11 specifically to tie it to this date).

Similarly, right-wingers in the LDP repeatedly submitted a bill restoring public maintenance funds for Yasukuni Shrine in the 1960s, and continued doing so until 1974. The bill never made it to an actual floor vote, let alone having a shot at passing, but the fact that this was even a part of the public discourse shows a striking rebirth of ‘imperial consciousness’, so to speak–of a desire to revive the old symbols of imperial nationalism alongside Japan’s economic rebirth.

This resurgent nationalism always carried a bit of the Pal myth, as Nakazato Nariaki calls it, alongside. After all, Pal was fundamentally a useful figure for a nationalist reading of Japanese history–his position as a ‘neutral Asian’ from India and, of course, his legal training lent him an aura of credibility and respectability, and those things could be mobilized to defend a nationalistic reading of the war years which sanitized Japan’s own involvement.

As I’ve already said, Pal’s own relationship to this idea is…complicated, to say the least. On the one hand, he did express concern during his 1952 visit that his narrowly-focused dissent, aimed at a specific interpretation of the nature of law was being misinterpreted to morally exonerate all Japan’s wartime actions, including its well documented mistreatment of POWs and civilians.

On the other hand, he didn’t fight the impression that he was ‘exonerating Japan’ that hard, and supposedly did eventually give permission for titles like ‘The Argument for Japan’s Innocence” to be attached to his work.

Honestly, the impression I get personally–though this is just an impression–is that particularly after his bid to spring into India’s national politics faltered in the early 1950s, Pal was just happy to have a context where he was relevant and thus did not push anything that could jeopardize that relationship for him. Particularly in his later years, when Pal was dogged by financial problems and had fallen out of the limelight politically, one imagines a chance to be treated like a seminal figure in legal history was, well, hard to turn down. Besides, it’s not like Pal had an aversion to right-wing nationalism himself, as his political relationship with early Hindutva movements covered last week indicates.

Indeed, another little tidbit uncovered by Nakazato was that, in the immediate aftermath of the Indian partition, Pal (who was Hindu but grew up in what’s now Muslim-majority Bangladesh) had backed Indian revanchist right wing groups pushing to annex territory from Bangladesh in the service of greater Hindu nationalism. He backed away from these groups later in his life, but they’re certainly indicative of some right-wing political leanings.

Regardless, Pal clearly felt comfortable by his final years with the role he’d taken on in nationalistic public consciousness in Japan. In 1966, Shimonaka invited him to tour the country once again–given that Pal’s health was already in decline by this point, the whole thing clearly had the atmosphere of a farewell tour.

And unlike in 1953, this time it was clear among Japan’s political leadership how useful Pal could be. He was received upon his landing by Kiyose Ichiro, who had been Tojo Hideki’s defense lawyer at the Tokyo Trials and later Japan’s speaker of the House of Representatives. Former Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, meanwhile, saw him off personally. In-between, he was interviewed by major networks (including NHK), received an official government honor (The Order of the Sacred Treasure, First Class), received at the Imperial Court, and given an honorary doctorate by the private school Nihon University, whose administrative leadership was closely tied to political conservatives.

It was this final PR blitz, at a time when far more people in Japan had TV and radio and thus could follow along than had been the case in 1952 and 53, that really earned Radhabinod Pal a place in the nation’s public consciousness.

When he died the next year, a memorial service held to honor him at Tsukiji Honganji in Tokyo attracted 300 dignitaries, including a speech in person by Foreign Minister Miki Takeo. Former Prime Minister Kishi went to Calcutta to console the Pal family, and one of Pal’s sons, Prosanto Pal, offered to send his father’s memorabilia to Japan. Those donations are now housed in the Shimonaka-Pal memorial Hall in Hakone.

Pal was not received totally uncritically, of course; the historian Ienaga Saburo in particular wrote several critiques of Pal’s judgment (in particular, Pal’s handling of evidence related to Japan’s own war crimes as well as a strong anti-communist bias in the judgment itself) in the 1960s and 1970s.

However, by this point Pal was simply too ensconced in the nationalist narrative of the war years to be dislodged effectively, particularly by a known left-winger like Ienaga.

Pal’s dissent has figured into nationalist narratives of Japanese history ever since, but experienced one big revival in particular in the 1990s and 2000s, when the ‘history issue’ and the question of Japan’s war responsibility flared into public discourse once again.

This revival was spurred by the 1991 filing of a lawsuit against the Japanese government by three South Korean ‘comfort women’, as they were euphemistically referred to–essentially women pressganged into sex work during the war years against their will–led by Kim Hak-sun. The elderly Ms. Kim’s class action lawsuit was filed in Tokyo District Court, and among other things referred to the comfort women program as a ‘crime against humanity’, invoking the language of the Tokyo tribunal.

That lawsuit–which in the end, led to government acknowledgment of wartime sex trafficking and a judgment in favor of the three women in 1998–sparked the revival of a broader debate around Japan’s war responsibility, a debate nationalistic conservatives naturally became embroiled in–and in which they deployed Pal’s work to support their agendas, given his own stance on the idea of ‘crimes against humanity.’

For example, Pal’s dissent features heavily in the textbooks produced by the Japan Society for history Textbook Reform, the right-wing thinktank set up in 1996 to attack ‘masochistic history.’ The books themselves are essentially revisionist works intended to rewrite Japan’s imperial history by portraying the country as the liberator of Asia, ignoring any suggestion that anything that might have happened during the war years was at all problematic.

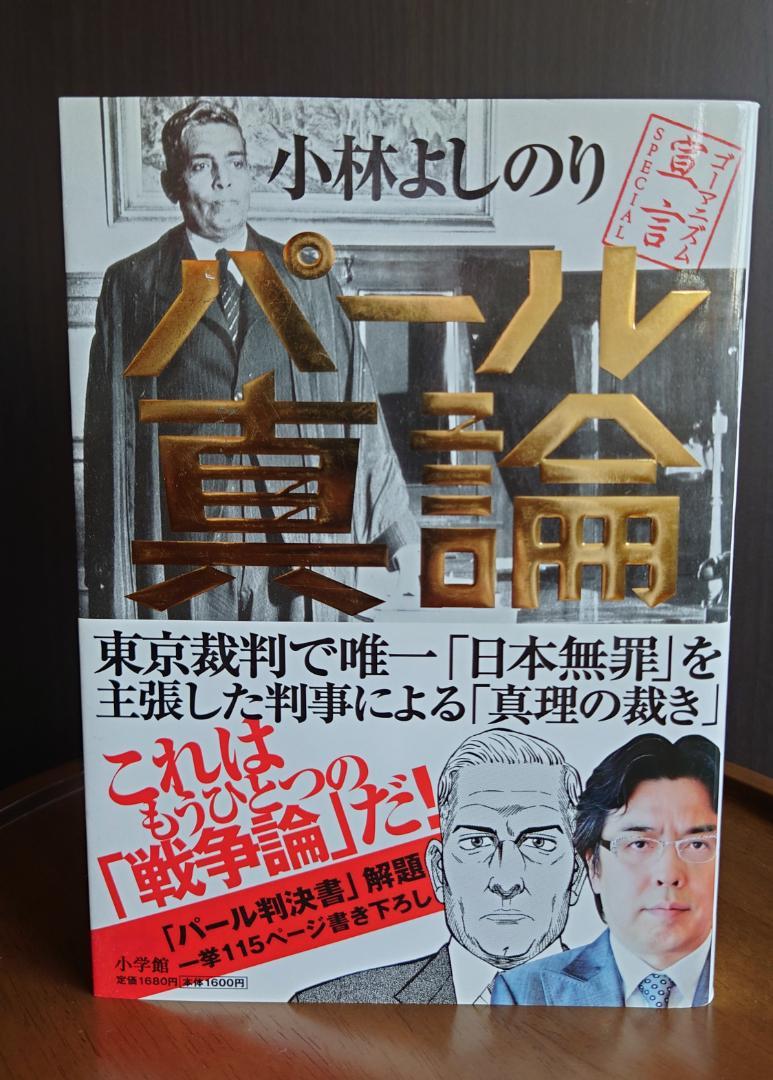

It’s also quite prominent in Sensoron, roughly ‘On War’, the nationalistic manga produced by Kobayashi Yoshinori in 1998. The manga launders Japan’s war in Asia in a similar way (going so far as to decry the Nanjing massacre as a fabrication, for example). It features Pal quite prominently in its depiction of the Tokyo tribunals. In one panel, Pal defiantly announces, “all defendants are not guilty! In the war / the United States / had absolutely no justice / Japan had justice of self-defense, furthermore of protecting the whole of Asia from the Western powers!”

Pal also features quite prominently in the 1998 film Pride: the fateful moment (Puraido: Unmei no Shunkan in Japanese), essentially a revisionist portrayal of Tojo Hideki’s time as Prime Minister of Japan where Tojo is shown as a brave Japanese patriot. The film was put on a recommended viewing list for parishioners by the nationalistic leadership of Yasukuni Shrine, and it portrays Pal (portrayed by Subesh Oroboi) as a voice of moral authority and reason against the vindictive and irrational Allies.

And of course, this is the time when “Pal monuments”, including the one at Yasukuni shrine, were set up. The first of these (that I know of, at least), was in Kyoto at its Ryozen Gokoku Shrine in the late 1990s–Gokoku, in this case, means ‘national defense’, and Kyoto’s Gokoku Shrine was set up in 1868 to honor designated martyrs of the foundation of the new imperial government (chiefly soldiers who had died in its foundational conflict, the Boshin War).

As such, it serves a similar focus to Yasukuni Shrine, just on a less prestigious level. And in 1998, it was the first to set up a ‘Pal Monument’ on its grounds.

The Yasukuni one, set up in 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the war, is of course far more famous–it’s what we started this discussion with last week, after all. The monument to Pal was erected at the front entrance of Yasukuni’s nationalistic museum, the Yushukan. The text of the monument, written by the shrine’s chief priest, is as follows: “Of all the eleven judges sitting on the bench… Dr. Pal was by far the most outstanding, not only in his erudition of international law, but in his resolution to achieve justice of law and his profound insight into civilization as well. Dr. Pal detected that the tribunal.. … was none other than formalized vengeance sought with arrogance by the victorious Allied powers upon a defeated Japan. He attested that the prosecution instigated by the Allies was replete with misconceptions of facts, being therefore groundless. Consequently, he submitted a voluminous separate opinion recommending that each and every one of the accused be found not guilty of each and every one of the charges in the indictment.”

Thus Pal’s transformation into the vindicator of imperial Japan was complete. From a man who ended up on the Tokyo Tribunal by accident, he had been refashioned–and had participated in his own refashioning, to an extent–into proof positive of “Japan’s innocence”.

Except, of course, that wasn’t what his dissent even said, though he himself seems to have signed off on that messaging later in life. And in the end, I think that’s the most important lesson to take away from Radhabinod Pal.

There’s a lot to unpack about his career–the link between right wing nationalism in India and Japan, for example, where today the ruling LDP maintains a close relationship with India’s ruling BJP, a descendant of the Hindutva movement Pal himself was on the edges of.

Indeed, Abe Shinzo visited India twice as PM (in 2007 and 2014), and both times was received with great fanfare–and both times made reference to Radhabinod Pal as a formative figure in India-Japan relations.

There’s also the fascinating angles of international law and its evolution–where, whatever Pal’s objections, the Tokyo and Nuremberg Trials have become formative precedents in the idea of responsibility for crimes against humanity.

Indeed, it’s worth noting that whatever Pal’s objections to the idea of crimes against humanity, history has proven him to be in the minority–he’s largely been left behind in that conversation.

All of these angles are fascinating, and you can dive deeply into them if you want–again, I can’t recommend enough Nakazato Nariaki’s Neonationalist Mythology in Postwar Japan as a starting point if you’re interested. But for me, I think the most important thing about Radhabinod Pal is how he represents the danger of something called the appeal to authority. When you see him mentioned by right wingers in Japan today, invariably it’s the same talking points: as an Asian, but one from India, he had special insight into the nature of the Tokyo Tribunal. He was an experienced lawyer. He wrote 1200 pages! And they all vindicated Japan. It sounds compelling, like there might be something there.

Notice how none of that deals with the substance of what Pal actually said, or meaningfully with his qualifications–which, as we’ve seen, have been mythologized heavily, and were not really better than the other judges.

That’s the appeal to authority–Pal was a judge and wrote all this, so it must be true! But of course, when you investigate it that all falls apart. And that’s a reminder that you should always dive deeper when you see claims that are surprising and challenging.

Not because they’re necessarily wrong, but because the proof is in the actual evidence, so to speak. You can’t just trust that because someone has credentials and wrote a lot, what they said is gospel truth. The way to actually understand is to question, to look deeper, to grapple directly with arguments instead of quibbling over qualification. Then, you can cut through it all–and maybe, at last, come to understanding.