This week, we’re looking at a very different kind of 60s protest movement: an attempt to build a cross-sectarian, non-ideological movement to oppose the American war in Vietnam. How did the anti-Vietnam War movement emerge in its Japan, and how did it simultaneously grow to a massive size and fail to have any appreciable political impact?

Sources

Havens, Thomas R.H. Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975

Andrews, William. Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture from 1945 to Fukushima.

Eiji, Oguma. “Japan’s 1968: A Collective Reaction to Rapid Economic Growth in an Age of Turmoil.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 13, No 12 (March, 2015)

Images

Transcript

Before we leave behind the radicalism of the 1960s, there’s one more movement I want to talk about, for a couple of reasons. First, I think any story of 60s radicalism would be incomplete without at least some discussion of one of the great causes of the time, and second in Japan specifically the movement to oppose the Vietnam War was very bound up with the wider world of student activism.

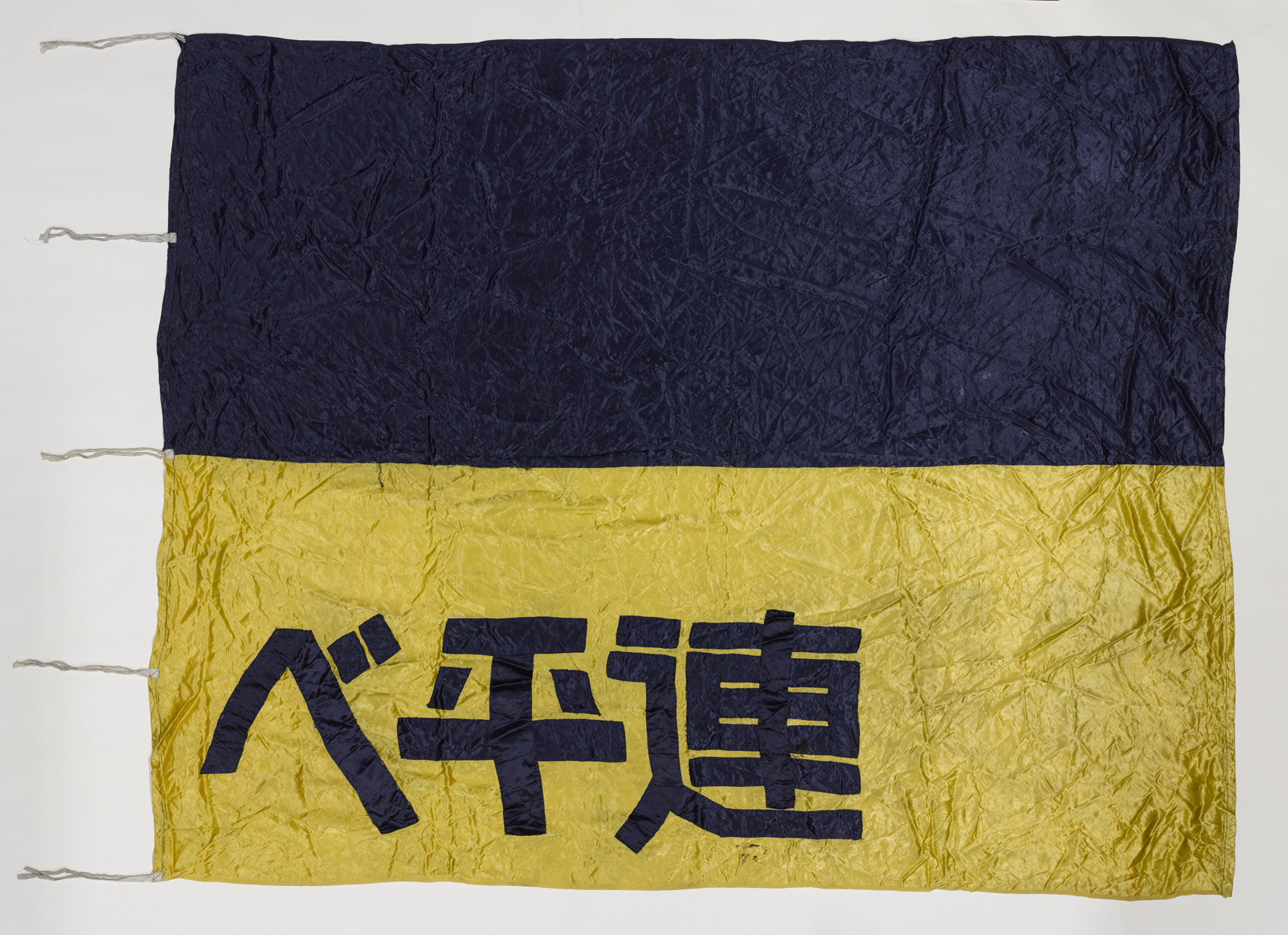

So today, it’s time to talk about the Betonamu ni Heiwa wo Shimin Rengo, roughly The Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam (though the official English name was the “Peace in Vietnam Committee.”)

But first, we should probably talk briefly about what the Vietnam War was and why it became such a flashpoint in Japanese politics.

So: what’s now the three countries of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia was, 100 years ago, a part of French Indochina–a French colony in Southeast Asia acquired via conquests in the 1800s. Colonialism being what it is, this was of course not very popular with the actual natives of the place, and by the 20th century there were flourishing anti-French resistance movements across the colony.

The most famous of these resistance movements was led by the Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh. Now, Ho would eventually align himself with the Soviet-led communist bloc as part of his pursuit of Vietnamese independence, but it is worth noting that there have always been open questions about how committed he was to communism as an ideology.

Like most communist movements in the 20th century, the Vietnamese one was a mixture of true believer communists and Vietnamese nationalists who simply bandwagoned with the communists out of convenience or belief that the communist party represented a valuable source of support. Ho Chi Minh himself might have been a bandwagoner onto the communist cause; famously, he did reach out to none other than Woodrow Wilson during the Versailles Peace Conference after WWI to get American support for Vietnamese independence (Wilson ignored his overtures).

It was only after this moment that Ho began to drift into the communist bloc, because the Soviet Union had a policy of supporting colonial independence movements as a way to both spread its political influence and undermine the capitalist powers.

Anyway: Ho developed a strong following in Vietnam specifically, and led both anti-French and, during the Second World War, anti-Japanese resistance in the name of both Vietnamese independence and revolution. After the war ended and Japan’s occupation of Southeast Asia collapsed, Ho–with the help of some Japanese officers who defected to his cause–then led a nine year war against the French that culminated in a Vietnamese victory in 1954.

After the French withdrew, Ho had hoped to set up a unified Vietnamese state–the Democratic Republic of Vietnam–but the United States in particular was worried about a communist movement taking power in Southeast Asia and intervened. In a series of negotiations in Geneva, the US eventually convinced the Soviet Union to pressure Ho Chi Minh into accepting a partition instead. His government would rule the northern half of the country, while a US-backed regime would rule the south. Eventually, a plebiscite–a nation-wide vote–would take place to reunify the two halves under a government chosen by the people of both. But that plebiscite was almost immediately canceled as both the governments of North and South Vietnam accused the other of not allowing for a fair election to take place.

The result was a divided Vietnam, and before long the two Vietnamese governments were involved in an undeclared conflict with each other. American attempts to prop up the South Vietnamese government–which was extremely unstable and dysfunctional and thus very unpopular compared to its counterpart in the North–first with training and equipment and then eventually with direct military involvement, represent the conflict we call the Vietnam War.

So, ok, that’s a quick intro to the conflict–and one that, yes, simplifies things a lot–but for us the more important question is: why did a war in Vietnam become a major issue in Japan, a country without a direct stake in the conflict?

Well, there were a wide variety of reasons–of course–but to touch on some of the major reasons: I think it’s hard to talk about Vietnam without talking about the role of television in depicting the conflict. Around the world, the Vietnam War was one of the first “TV conflicts,” so to speak–allowing people a far more immediate and visceral look at the conflict, where in the past images of war had been far more delayed–and less immediate, given the power of the moving image.

That was particularly true because that TV coverage captured some of the more horrific tactics employed by the US, such as burning villages suspected of being hideouts for the Viet Cong (a pro-North Vietnam guerilla movement). This was not the first time civilians were targeted in war, of course–but it was the first time people saw it happening on the nightly news, compared to just photos of the aftermath.

Second, Japan was, in a sense, involved in the war–at least indirectly. Though the US occupation of Japan had officially ended in 1951, part of ending that occupation had been agreeing to a massive American military presence in Japan. Indeed, the entirety of Okinawa Prefecture was still under direct US administration in the 1960s, in the form of USCAR–the US Civil Administration for the Ryukyu Islands, a government run by the American military.

American bases in Japan–especially Okinawa–provided a vital logistical link in the American war effort. Japan-based bombers hit North Vietnam; Japan was a common destination for units being rotated off the front lines; US navy ships supporting the conflict were often based out of Japan, or passed through Japan on their way to South Vietnam.

There were, to be sure, other Asian allies more directly involved in the conflict–most notably South Korea, which outside of the two Vietnamese governments and the US had the largest number of troops fighting directly in the conflict–but Japan was far from uninvolved in the Vietnam War.

This had a couple of important effects within Japan itself. First, though not many people in Japan wanted to talk about this, the war made Japan quite a bit richer. Just as the Korean War had helped Japan’s economy recover from the devastation of World War II, the Vietnam War kickstarted Japan’s economic growth. Quite a few Japanese industries were given contracts by the US military for everything from beer and food to medicine or clothing, and even when that wasn’t the case–many American-based consumer goods companies were given military contracts, allowing Japanese businesses to take up the slack, so to speak, in the US market while US companies focused on military requisitions. It’s been estimated that the Vietnam War added almost a billion dollars a year, directly or indirectly, to Japan’s GDP while it was going on.

And perhaps the sense of guilt that Japan was profiting from the conflict helped to drive some towards the anti-war movement. For others, however, that pacifist stance had nothing to do with the economy. It was driven instead either by a general sense of opposition to war–after all, World War II was only two decades in the past at that point–or a sense of “atonement”, so to speak.

After all, Japan had not that long ago been involved in an imperial war of aggression against its Asian neighbors. For many young Japanese in particular, opposition to the Vietnam War was a way to atone for that sin, to show that they did in fact care about their fellow Asians.

Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, much of the opposition to the war was driven by simple anti-American sentiment. In part, that sentiment was driven by the not unjustifiable feeling that American intervention in Vietnam was causing a great deal of harm–without accomplishing very much in the way of actually improving lives for the people of the country.

But in Japan specifically, anti-American feeling in the 1960s was a bit more complex than that. For sure, there was an element of the sentiment that was simply critical of American policy in Southeast Asia–particularly as revelations about atrocities committed by American troops began to appear in the press.

But in Japan specifically, criticism of the Vietnam War was also driven by the history between Japan and the US. Initially, after the Second World War, public opinion in Japan had been fairly favorable toward the US–but by the late 1960s, that had begun to shift. After the occupation, revelations about the extent to which the US had suppressed postwar discussion of things like the famines caused by its war-era blockades or the atomic bombs came to light. During the 1960s, there was also substantial fear that Japan’s role as a base for US forces in Asia would bring it into the line of fire in any conflict with the Soviet Union or China. At the same time, the continued American military presence in over 150 sites around the country led to substantial friction with the locals. Most tragically, between 1952 and 1977 some 500 Japanese citizens were killed by on- or off-duty US personnel. Moments like this, combined with a growing sense of assertiveness as Japan’s economy rebounded, led to a growing willingness to critique the USA.

For example, a newspaper survey in 1964 found that 49% of Japanese said America was their favorite foreign country (compared to 4% who said they disliked it); by 1973, a mere 18% of respondents said they liked America, compared to 13% saying they disliked it.

So far, though, all we’ve talked about are reasons why there was opposition to the Vietnam War in Japan–not the Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam, or Beheiren–the Japanese acronym by which it was known. So: where di the Beheiren come from?

The answer is interesting; the Beheiren emerged from rather unremarkable beginnings before becoming an enormously successful activist group. The organization was first set up in 1965 primarily as a clearinghouse of Japanese intellectuals opposed to the war effort: it was led by the novelist Oda Makoto, joined by intellectuals who had been a part of the 1960 anti-security treaty protests like Tsurumi Shunsuke and Maruyama Masao. Interestingly, it was not just left-wing intellectuals: Ishihara Shintaro, the right-wing future LDP politician, was actually on the initial shortlist to lead the organization.

The initial goal of the Beheiren was to model its anti-war activism after the 1960 anti-security treaty protests. It was to be a clearinghouse of citizen activists, not tied to existing political parties (and thus not weighed down by either their historical baggage or their doctrines). Anyone could join so long as they opposed the war effort–The three tenents of the organization were “Peace for Vietnam”, “Vietnam for the Vietnamese,” and “Stop the Government of Japan from cooperating in the Vietnam War.” These are all pretty broad slogans, and the hope was that by avoiding political radicalism and factionalism, the movement would have more mass appeal and be able to mobilize a wider chunk of society.

This is also why Oda Makoto was chosen to be its initial leader: he was a good public speaker, but not known for his politics (and thus not someone affiliated with one or another existing political movement). He was also very committed to the idea of the Beheiren as non-doctrinal, saying, “‘.Let’s junk radicalism based on words…‘This is a very complicated movement. You can’t define it. I myself don’t know exactly what it is.’ Indeed, the movement was so broadly defined that the name Beheiren wasn’t even settled on until an entire year after its founding.

All of which looks good on paper, but the reality is that the Beheiren did not exactly get off to a flying start. Its first demonstration in April, 1965 attracted only 1500 people, primarily writers, artists and academics. Its biggest successes involved attracting non-JApanese people to its rallies, such as a 1965 teach-in attended by Carl Oglesby, a leader of the American protest organization SDS, or Students for a Democratic Society. The next year, Beheiren organized a trip to Tokyo for the intellectuals Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, as well as the anti-war academic Howard Zinn.

Moments like this were useful in terms of bolstering the Beheiren’s notoriety overseas and drawing global attention to the anti-war effort in Japan, but as you might imagine they didn’t do much to make the Beheiren a household name. After all, names like Oglesby, Sartre, de Beauvoir and Zinn might get the attention of students and intellectuals–but how many average people had heard of them?

That’s not to say the Beheiren was totally ineffective within Japan in its early years. The group was able to sustain a monthly demonstration on the first Saturday of every month from September 1965 to October, 1973. It also organized successful antiwar concerts in Osaka and Tokyo in 1966 and 1967 respectively, and managed to get a decent following in some unions, leading to a successful strike on October 21, 1966 by 2 million workers.

Even victories like this, however, were a bit hollow; the strike was called not just against the war but for better wages, and journalists interviewing the strikers found that most did not even recognize key terms related to the war (such as knowing who the Viet Cong were).

It wasn’t until 1967 that the Beheiren got the jolt it needed to really propel itself into the popular consciousness, thanks to a tragic accident in the heart of Tokyo. As we’ve already covered, Japan itself was central to the American war effort, in part because the country was home to so many American military bases. The bombing effort against North Vietnam, in particular, relied on logistics support from those Japanese bases, one component of which was jet fuel–some 4.84 million liters of aviation fuel were moved between bases on Japanese rail lines every single day to support the war effort. And on August 8, 1967, a train carrying some of that jet fuel collided with another freight train.

The result was a massive conflagration in the heart of Japan’s largest city, one directly traceable to the war in Vietnam. That experience in turn began to galvanize stronger anti-war sentiment in the city, particularly among students, and especially among one of the most vocally anti-American groups of students: the various Marxist factions of the Zengakuren.

Which leads us, by the by, to an important aside. All of this is happening, it’s important to note, in the lead up to (and pretty soon, during) the various student rebellions of 1968. While I’m treating groups like the Zengakuren and Beheiren separately here, there was some overlap and interplay between them–particularly, as we’ll see, because it was a Zengakuren action that helped to in turn to mobilize more support for the Beheiren.

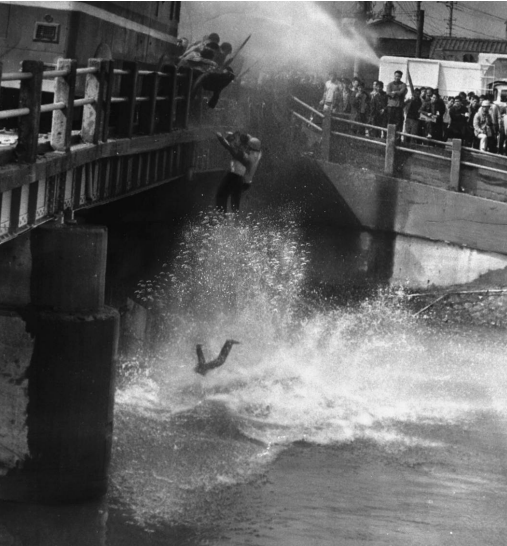

That action was a mass protest at Haneda Airport called for October 8th in response to two things: first, the train car fire, and second, the announcement a few weeks later that the Prime Minister, Sato Eisaku, would take a trip to the pro-US regime of South Vietnam himself.

Zengakuren protestors descended on the airport to try and stop Sato’s departure; they were, in the end, completely unsuccessful, as a few thousand students (the best estimates I’ve seen suggest 2300) were met by around 4000 riot police armed with water cannons, nets, batons, and tear gas–all later weapons used during the campus occupations of 1968. As a result, the students–who’d planned to push through Benten bridge to the southwest of Haneda onto the runway itself–were blocked out, but continued to press their attack.

In the press, one of the students, 18 year old Yamazaki Hiroaki of Kyoto University, was killed in the advance–it’s unclear exactly how. He was either killed by riot police or run over by fellow students who had hijacked a police vehicle; the fault for his death remains murky to this day.

What is clear is that images of the violence, broadcast on Japanese TV over the subsequent days, did not make the Zengakuren look great–but they also made the police look awful, particularly given that after Yamazaki’s death the Zengakuren backed off and tried to hold a vigil for him, which the police then attacked and fired tear gas into.

The battle at Haneda was a major step in radicalizing the Zengakuren, and definitely contributed to the campus occupations the next year–but the hamfisted government response also helped to drive support towards the antiwar cause, particularly when yet another street battle at Haneda (this one over a planned trip by Sato to the US) resulted in similar levels of violence, though fortunately no deaths.

Growing numbers of people were now participating in activism opposed to the war; for example, the Beheiren called for a nationwide strike on October 21, 1967 (the same day as the March on the Pentagon) and got a quarter million workers to participate, this time with a clearer pacifist message. However, the real coup came on November 134, when the Beheiren revealed what they called the “Intrepid Four.”

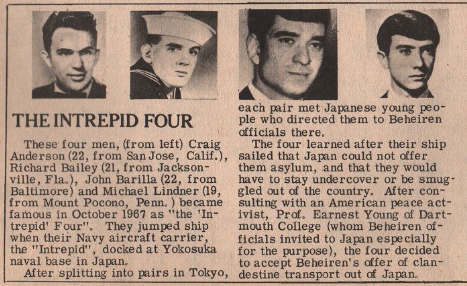

These were four crewmen–Craig Anderson, Richard Bailey, John Barilla, and Michael Lindner–of the USS Intrepid, an aircraft carrier stationed in Yokosuka south of Tokyo. In late October, the four sailors decided AWOL during their shore leave in Tokyo–somewhere along the way, they met a radical student from the University of Tokyo who both spoke a little English and had connections to local Beheiren activists who could get the four to safehouses. The four were taken out of Tokyo, interviewed by the Beheiren and gave them statements, and then the organization announced their desertion. The Beheiren’s English statement read in part: “You are now looking at four deserters. Four patriotic deserters from the United States Armed Forces. Throughout history, the name deserter has applied to cowards, traitors and misfits. We are not concerned with categories and labels. We have reached the point where we must stand up for what we believe to be the truth … This overshadows the consequences imposed by the categories.”

Eventually all four were smuggled out of Japan and to Sweden via the Soviet Union; last I’d heard, Anderson is still living in the US (and eventually served prison time for deserting), while Barilla is living in Canada and the other two are still in Sweden. But more importantly for us, the Intrepid Four absolutely blew the Beheiren into the big leagues. The group made front page news, and its demonstrations began to attract way more support–the organization’s central offices in Tokyo received 2000 letters endorsing their actions within a week of the announcement, and its monthly protests began to get far greater attendance.

It also, by the way, made the Beheiren notorious for being willing to help American deserters, and it’s true that the group did put a fair amount of effort into that. The results were not by any means spectacular; about 50 American servicemen reached out covertly to the Beheiren to ask for help deserting over the remainder of the war, and the group only accepted about half. Its volunteers also experienced frequent cultural clashes with the Americans; one Kyushu-based member later complained, “They were an awful bunch….Staying at a detention centre would have been better for them. If they got hungry, they’d mooch around the kitchen, and if they wanted to eat meat they’d just take a knife and chase after a chicken.’

Helping deserters also made the group a target for American spies–one such spy, faking desertion and ending up with a group of Beheiren members and fellow Americans in Hokkaido, turned in the whole group to the authorities in February of 1969.

But while helping deserters put Beheiren on the map, and are probably what the group is best known for outside Japan, it’s really the group’s other activities that were far more impressive and demonstrative of its broader appeal.

For example, in January, 1968, the Beheiren spearheaded a massive effort in Sasebo in Kyushu, protesting plans to dock the American nuclear aircraft carrier USS Enterprise in Sasebo’s harbor as the ship prepared to make way for Hanoi, there to launch more bombing missions against North Vietnam.

It is worth noting that the Enterprise was both the first nuclear powered ship and the first one capable of carrying nuclear weapons to visit Japan (outside of Okinawa) since the ruling Prime Minister Sato Eisaku had introduced his so-called three non-nuclear principles, the last of which was that the government would not allow nuclear weapons to even transit through Japanese territory. Concern that the Enterprise was carrying nukes in violation of those principles–and that Sato was merely offering a sop to the anti-nuclear movement in Japan with his principles–no doubt helped drive the ferocity of the protests.

Indeed, 19 other nuclear-powered or nuclear-equipped US military vessels had visited Japan between 1964 and the start of 1968, and to my knowledge, only one of them had been met with any protest–the USS Barb, a nuclear submarine which had docked at Yokosuka in July, 1967 and which was met with a few hundred Zengakuren protestors. The Enterprise, as we’ll see, is going to get a bit more of a reaction than that.

And this begs the question why. Partially, I think we can explain the response due to the growing strength of the anti-war movement and especially the Beheiren, and because of the non-nuclear principles Prime Minister Sato had just announced. I do think there’s also something to the idea of the Enterprise protests as a manifestation of Japan’s so-called “nuclear allergy”–a general sense of pervading suspicion of nuclear power given Japan’s rather unique history, to put it mildly, with the subject.

The local Beheiren chapter had initially planned to rent a private airplane the day the Enterprise was scheduled to dock and bombard the ship with flyers encouraging its sailors to desert. The local flight chartering agencies were not interested in getting involved, however, and all refused to do business with the group. Instead, the Enterprise was greeted by two giant signboards, one ashore and one displayed on a hired fishingboat, with that same message.

But it was the protests, really, that made headlines. Between the Beheiren, a combination of communist, socialist, and union activist protestors, radical students, and a couple of anti-war new religious groups, Sasebo police estimated some 46,000 protestors were active in the city when the Enterprise docked on January 18. Nor was the issue confined to Sasebo itself; over 90 rallies or demonstrations took place outside American consulates just in the Kansai area, as well as others in front of the Prime Minister’s Residence and US Embassy in Tokyo.

Just as had been the case with Haneda Airport, the Zengakuren factions present at the protests launched themselves into a pitched battle with the cops by trying to storm the Sasebo base–the police counterattack saw 500 people arrested and hundreds more seriously injured, without a single student getting anywhere near the base itself.

Local bystanders, however, generally sympathized with the protestors–the cops were seen beating students who were already down and in some cases dragging injured students who were being treated by others away to assault them. It’s true that the local community was probably not terribly sympathetic to the Americans–bases are noisy and dirty and full of young men who are not, to put it mildly, always on their best behavior, and thus do not always make great neighbors. So many of them may have been previously inclined towards the protestors to start with–but after the protests, they were even moreso–local fundraising easily covered the costs of both bail and medical fees for the students, a clear indicator of the level of sympathy for the cause.

The Enterprise, though, was able to dock unimpeded–though neither it nor any other nuclear carrier returned to Sasebo until 1983, and then guarded by hundreds of ships from the Japan Coast Guard.

In the aftermath of the Enterprise incident, local Beheiren chapters turned their attention to other American military bases scattered throughout Japan, from a field hospital in Ouji in Tokyo to the Tachikawa Air Force Base (now JSDF Camp Tachikawa). These localized protests were, like some of the support for students in Sasebo, often driven just as much by anger about the bases–which were loud and dangerous–as specific anti-war feeling, but they were effective. Over the course of 1968, the protests spurred American commanders in Japan to agree to a reorganization of their bases that would see about 1/3rd of American bases in Japan either shuttered or turned over to the JSDF.

The Beheiren was gathering momentum, undoubtedly, but that sense of momentum is somewhat deceptive. Beheiren protests were gathering steam and drawing support, but had not succeeded in putting much pressure on the Sato government to change its stance toward the war–to say nothing of the Americans, who yes had agreed to those base closings but certainly were not changing much about their actual policies in Southeast Asia.

And remember, it’s now 1968, and all those headlines drawing attention to the Beheiren are about to go somewhere else–the summer of 1968 is the beginning of the student uprisings we talked about over the course of the last two weeks. Radical students, particularly members of the Zengakuren, had been more than happy to work with the Beheiren, of course, but the priorities of the two groups were different–the Zengakuren factions were opposed to the war in Vietnam, but far more overtly revolutionary where the Beheiren was a specific policy-focused endeavor.

And the student revolution would draw a lot of time and energy away from the Beheiren. For example, October 21 was by this point called International Anti-War Day, and the Beheiren planned a whole bunch of demonstrations and strikes as usual for a day where it would get a lot of publicity–only to be left completely behind as radical students ended up launching what can only be called a pitched street battle in Tokyo as they stormed Shinjuku station and attempted to set up a “Liberated Quarter.” Seriously, I will have to talk about this at some point but there’s no way to do it justice here.

The next year’s International Anti-War day unfolded in similar style; Beheiren mobilized 10,000 protestors in Tokyo for the event, but their protests were wildly overshadowed by a new round of street fights between the police and Zengakuren (leading, by the way, to a record setting number of arrests for a protest–1689 people in a single day).

Even when the organization was able to strike out on its own out of the shadow of student radicalism, the results were mixed. For example, in the spring and summer of 1969, Beheiren-affiliated musicians began doing the most 1960s thing imaginable: holding guerilla anti-war concerts in the plaza outside Shinjuku station.

Apparently the most popular song was called Tomo yo (Friend!), with its chorus going: ‘Friends in the darkness before the dawn,friends, let’s light the flames of the struggle, the dawn is near.’ So yeah, basically the most 60s thing imaginable.

The police broke up these concerts, but the participants simply came back the following week–what eventually stopped them outright was the legal redesignation of those plazas as passageways, allowing anyone who obstructed them–by say, setting up a concert–to be arrested as a public nuisance before anything could really get going.

The Beheiren certainly was not falling apart, by any stretch of the imagination–it was an active participant in protests in November, 1969 around Prime Minister Sato’s trip to the United States (to negotiate the return of Okinawa in exchange for allowing continued US military presence on the islands, much to the dismay of the pro-peace left). It also participated in the protests around the renewal in 1970 of the US-Japan security treaty, which were substantial–though nowhere near as disruptive as the 1960 protests around the original signing of the treaty.

But ultimately, though the Beheiren was able to continue holding its monthly protests and drawing on support, it was not able to meaningfully affect government policy. Japan continued to tacitly support the US war effort in Vietnam–which was at this point winding down from the American perspective anyway, Richard Nixon having won an election in 1968 on the promise of “Vietnamizing” the conflict. Prime Minister Sato was still able to call a snap election in 1969 and crush the Japan Socialist Party and the rest of the left once again.

He’d even go on to win a Nobel Peace Prize in 1974 for his non-nuclear principles, even though it’s reasonably clear he let the US get away with violating them all the time.

And of course, the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty was announced in 1971 (and carried out in 1972) to substantial fanfare.

Why, despite its support, did the Beheiren–or anyone else–fail to substantially impact actual policy? It’s a hard question to answer, but I suspect at least part of the issue was the diffuse nature of the group itself. The very openness of the group meant that its goals were very broadly defined–”peace in Vietnam” is all well and good, but what did that actually mean? Nobody was quite sure, making it hard to translate momentum into action–and thus naturally leading to the loss of momentum over time.

Plus, the Japanese government in 1970 was not what it had been in 1960. Prime Minister Sato understood that while the 1960 protests had been driven by concerns about the treaty, they had been accelerated by the heavy-handed response of the government to the initial wave of protests–ignoring the traditions and rules of the Diet to force the treaty through as quickly as possible. As long as Sato did not give people someone to rally against by acting that way, there was little to worry about–the movement would burn out on its own.

And that is exactly what happened. The Beheiren would soldier on until January 26, 1974, about one year and three months before the final fall of South Vietnam to the North. At its final meeting, Tsurumi Shunsuke, one of the founding figures of the movement, gave a speech to around 1000 remaining members saying, “”another day I think Beheiren—although not as Beheiren—will want to make an appearance once again. Beheiren is dissolved. Long live Beheiren!”

The Beheiren ultimately, at least to me, represents another side of the activism of the 1960s–an attempt to move away from the intense sectarianism that often defined radicalism at the time. It was not, ultimately, successful in bringing peace–or stopping the wider decline of the Japanese left–but it does serve as an important reminder of the potential of grassroots activism in a country where today, it often feels like political apathy reigns supreme over anything else.