We’ve talked about cultures that had a formalized, bureaucratic process for getting revenge. But what do you do when you’re not legally allowed to retaliate against the man who killed your father? Shi Jianqiao devoted her life to revenge, captivating the Chinese populace with her filial piety and her poetry justifying her crime.

Featured image: A photograph of Shi Jianqiao taken when she was a young woman. (Image source)

Shi Congbin, Shi Jianqiao’s father. According to Shi Jianqiao, he was an extremely virtuous man. (Image source)

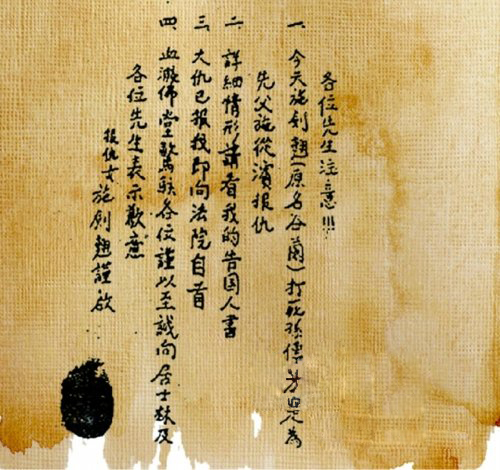

One of the pamphlets Shi Jianqiao created to explain her motive for murder. (Image source)

Sun Chuanfang, before his fall from power. (Image source)

Zhang Chongchan, the “Dogmeat General.” (Image source)

Sources

- Eugenia Lean, Public Passions: The Case of Shi Jianqiao, Mass Culture and Collective Sentiment in Republican China. University of California Press.

- Jonathan K Ocko and David Gilmartin. “State, Sovereignty and the People: A Comparison of the ‘Rule of Law’ in China and India” Journal of Asian Studies 68, No 1.

- Daniel Asen, “Approaching Law and Exhausting its (Social) Principles: Jurisprudence as Social Science in Early 20th Century China.” Spontaneous Generations 2, No 1)

- Qiliang He, “Scandal and the New Woman: Identities and Media Culture in 1920s China”, Studies on Asia 4, No 1

- CHINA: Basest War Lord

- Criminal Code of the Republic of China