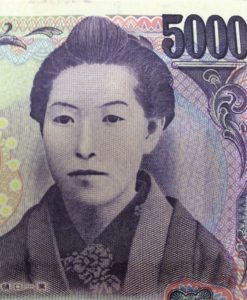

This week, we explore the career of the first woman to make a big splash in modern Japanese literature: Higuchi Ichiyo. We’ll talk about her story, her writing, her legacy, and her tragically short career — and I’ll spend a lot of time talking about how much I hate Mori Ogai!

Sources

Omori, Kyoko, “Higuchi Ichiyo” The Modern Murasaki. Ed., Copeland, Rebecca and Melek Ortabasi.

Tanaka, Hisako. “Higuchi Ichiyo. Monumenta Nipponica 12, no. 3/4 (October 1956-January, 1957)

Mitsutani, Margaret. “Higuchi Ichiyo: A Literature of Her Own.” Comparative Literature Studies 22, No. 1. (Spring, 1985)

Images

Calling the character a daughter of a “sex worker” isn’t exactly specific. It’s too broad a term. Was she the daughter of a geisha? An oiran? A yuujo? Just say “prostitute.”

I’ve been trying to move away from the term prostitute because it’s so often read as a pejorative, which is not my intention. I know that not everyone feels that way about the term, but I would not want to have anyone read me as condemning someone who is in that industry for whatever reason.

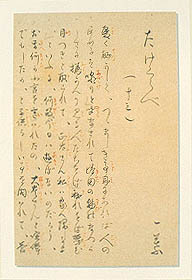

I would assume she’s a yuujo in the original but I haven’t actually read Takekurabe in the original because my classical Japanese is a bit rusty; Wakaremichi is the only one I’ve had a chance to read in the original language.